Boycott: The Wild Origins Of The Term Explained

Although the word “boycott” is nowadays widely used whenever a product or person is protested, many don’t realize that it first came into use as part of eviction resistance and a rent strike. As Irish farmers in Ireland faced starvation alongside mass eviction, in 1879, a group known as the Irish National Land League set out to affirm the rights of Irish tenants.

In the process, a man named Charles Cunningham Boycott ended up becoming the poster child for resisting landlordism, and within several years his name had become part of the lexicon of numerous languages. Although the boycott of Boycott didn’t solve all the problems Irish tenants were facing, it led to several significant reforms while simultaneously setting the stage for the Irish nationalist movement.

As of August 2020, millions of people are at risk of eviction in the United States alone. In response to such a crisis, it’s important to take note of what those before us have tried and accomplished. This is the wild origins of the term “boycott” explained.

Inequality in 1800s Ireland

Throughout the 19th century, the majority of the land in Ireland was owned by a comparatively small number of families. This came out of the fact that in the 17th century, “England confiscated in excess of three million acres of land” from Ireland and set the stage for the landlord system, according to “The Land-Tenure System in Ireland.”

There were no protections, rights, or leases for Irish peasants who rented land; “instead, they became tenants at will who could be evicted at any time and for any reason.” And by the 1870s, 50 percent of the land was owned by 750 families, at a time when Ireland’s population hovered around five million. The rent for Irish tenants was 80-100 percent higher than the rents charged in England for similarly small plots. But there was little choice other than to pay, because otherwise the option was eviction, which was described as “tantamount to a sentence of death by slow torture.”

In order to survive, Irish farmers had to squeeze out as much money as possible from the land they were renting. However, there was rarely much money left over after paying rent and “less than one acre of land [left] to grow food for the traditionally large Irish family.” And when potato crops were affected by blight, the situation got dire.

The Irish Famines

During this whole time, Ireland was facing “an Gorta Mór,” also known as the Great Famine, which affected potato crops around Europe. By 1841 in Ireland, the majority of Irish people depended on potato crops as their main, if not only, source of food because it could be easily grown and didn’t require especially fertile soil. And although the potato crop had experienced blight before the Great Famine, people in Ireland had few other options.

It wasn’t as if there was no food in Ireland during an Gorta Mór, which lasted until 1851. According to The Washington Post, during one of the famine years, “more than 26 million bushels of grain were exported from Ireland to England.” Export of livestock also went up during the famine years. But there was little for Irish farmers to do. If they ate into what they were farming for rent, they’d face eviction. If they didn’t eat, they’d starve to death. It’s estimated that roughly one million people died as a result of the Great Famine, while over two million more emigrated from Ireland during that time. The potato crop failed again between 1877 and 1881, during which time poultry was also affected by a cholera epidemic.

“The Land-Tenure System in Ireland” explains that people renting land in Ireland “were forced into dependence on a single crop by greed institutionalized in a legal system that gave landlords tremendous power to demand ever increasing rents.”

The Irish Land War

By 1879, thousands of Irish farmers faced eviction while their landlords sought to raise their rents. Early that year, several tenants of Canon Burke reached out to James Daly, editor of the Connaught Telegraph, who helped them organize a protest meeting. And according to Irish Origins, despite the fact that the Catholic Church had warned people not to attend, there were upwards of 8,000 people at the first meeting.

More and more meetings and protests were organized in Mayo and by that summer, the Land League of Mayo, founded by Michael Davitt, had “organized successful resistance to threatened evictions.” In October, the organizing group was renamed Irish National Land League and Charles Stuart Parnell was set as its figurehead.

The goal of the land league was a complete abolition of landlordism in Ireland. Although there were some reforms advocated, such as reductions in rent, “these were very much seen as interim measures.” This movement became known as Cogadh na Talún, or the Irish Land War, and is considered to have lasted until the summer of 1882, but can include subsequent conflicts up to 1909.

The Three Fs

The Land League’s campaign for tenants’ rights and the abolition of landlordism was based around the Three F’s, which had been the aims of earlier reformers. The Three F’s were based around “fixity of tenure, fair rent, and free sale of tenant rights,” according to the Michael Davitt Museum.

Essentially, what they were fighting for was rent control, the freedom to sell without landlord interference, and the right to live without the threat of eviction if one were paying a fair rent. Ultimately though, the long-term goal of the League was peasant proprietorship.

According to “A New Look at the Irish Land Question,” the conflict between tenants and landlords wasn’t concerned “about divided property rights between owner and tenant […] but rather concerns a different concept of property altogether, and the issue between landlord and tenant in Ireland was whether property was to be thought of as private or as in some sense communal.”

So who was Charles Boycott?

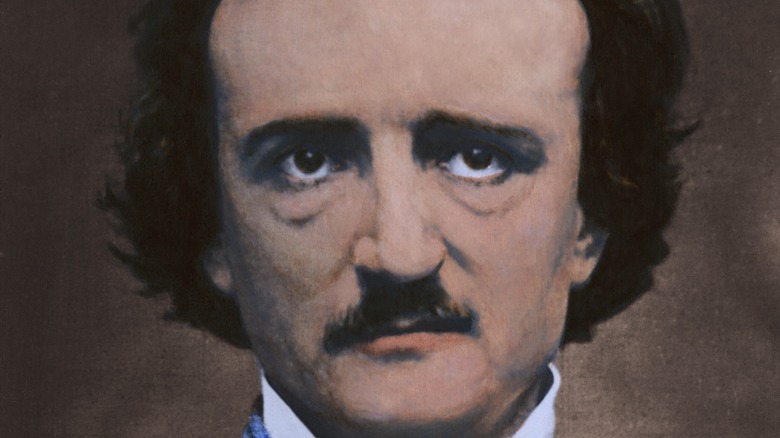

Born in March 1832, Charles Cunningham Boycott was an English landlord in Ireland for several years before he was hired as a land agent by John Crichton, the Earl of Erne. According to The Irish Independent, Lord Erne was an “absentee landlord,” and so Boycott was recruited to collect rent and make sure the 1,500 acres in County Mayo were maintained.

History of Yesterday writes that before becoming a landlord, Boycott aspired to join the military, but he was expelled from the Military Academy in 1849, one year after enrolling, because he failed a test. However, since his family was rich, they were able to buy him a place in the 39th Regiment, which is what ended up bringing Boycott to Ireland in the first place.

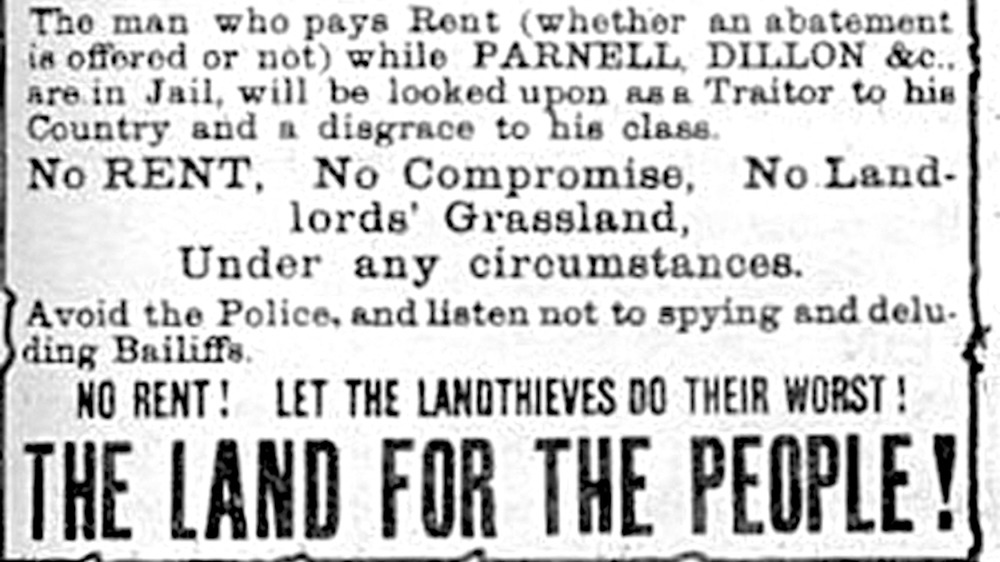

In 1880, the harvest was so bad that in the fall, “Boycott offered the farmers on his land a rent reduction of 10 percent,” Bustle reports. The farmers insisted that this was too small of a reduction considering their situation and demanded 25 percent instead. After the Earl of Erne denied the 25 percent reduction, some of the farmers decided to protest the rent and “11 of the tenants ended up never paying their rent.”

An attempted eviction

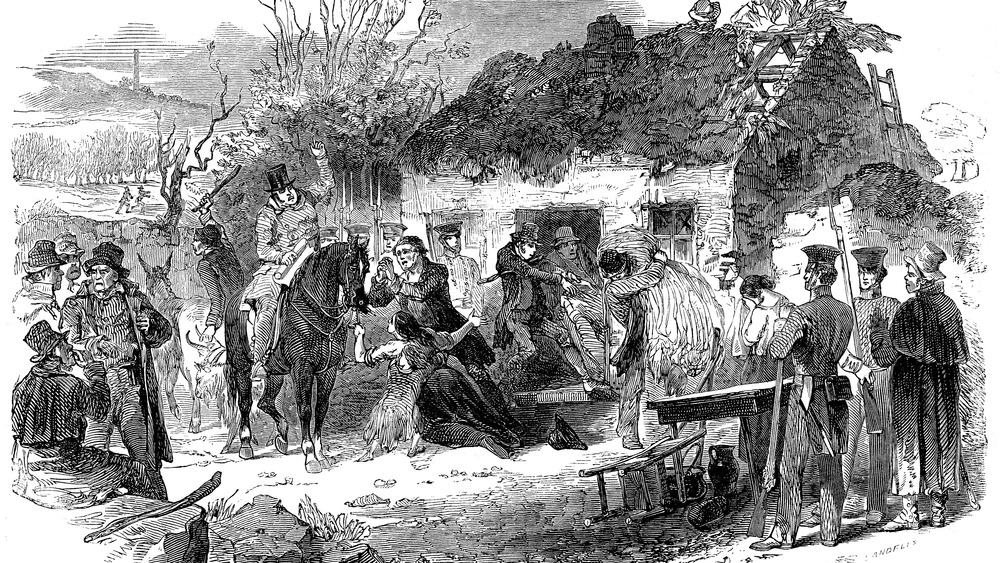

Led by Michael Davitt, Charles Parnell, and the Irish National Land League, the Irish tenants refused to pay the rent with anything less than a 25 percent reduction. In response, Charles Boycott tried to evict them. However, according to Bustle, since by law eviction notices were required to be served to the head of the household in order to be official, Irish women “started throwing rocks and manure at the Constabulary until they were unable to serve the notices.” Since the eviction notices weren’t technically served, no one had to leave their house.

Brooksy Society writes that in 1880, while making a speech to Land League members, Parnell asked, “What do you do with a tenant who bids for a farm from which his neighbor has been evicted?” The crowd responded with “Shoot him!” and “Kill him!”

But Parnell had another idea: “When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him – you must shun him in the streets of the town – you must shun him in the shop – you must shun him on the fair green and in the marketplace, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of the country, as if he were the leper of old – you must show him your detestation of the crime he committed.”

Boycotting finds its name

And that’s exactly what the Irish tenants did to Charles Boycott and anyone who associated with him. The name stuck soon as well. According to Tennessean, one story about how boycotting got its name involves Father John O’Malley and journalist James Redpath: “When the people ostracize a land-grabber we call it social excommunication, but we ought to have an entirely different word to signify ostracism applied to a landlord or land-agent like Boycott. Ostracism won’t do — the peasantry would not know the meaning of the word — and I can’t think of any other.” Father John reportedly was the one who suggested “boycott” and the rest, as we now know, was history.

Meanwhile, the entire community isolated Boycott by September, 1880. Factsite writes that people stopped working in his house and his fields, businessmen stopped doing business with him, and even the mailman stopped coming round. With businesses boycotting Boycott, he couldn’t even easily buy food. Writing to the London Times, Boycott lamented his situation and claimed that there was a “danger to my own life, which is apparent to anybody who knows the country.”

However, it’s questionable whether Boycott’s life was actually in danger. Modern Distortions writes that although acts of violence did occur during the Land War, “were the exception rather than the rule and never were official League policy.” Bearing this in mind, it’s possible that the danger Boycott faced was merely the same danger of starvation the Irish tenants faced.

Finding men to harvest

Charles Boycott was left with no one to work the fields he was meant to be overseeing, so eventually Boycott was forced to hire 50 men to come to County Mayo just to harvest, despite the fact that he only needed 12. Apparently, according to History of Ireland, after hearing about Boycott’s predicament, landowners in Ulster, where Lord Erne lived, decided to rally together volunteers to assist Boycott. The men were “mainly Orangemen from Cavan and Monaghan” and their mission was known as the Boycott Relief Expedition.

Boycott was also forced to hire at least 900 soldiers to escort the workers to the fields, bringing them in from Claremorris to Ballinrobe. They stayed throughout the harvest and “on 27 November [the soldiers] left along with the relief expedition, and it was reckoned that it had cost up to £10,000 ($13,800) to save a harvest worth at most £350 ($485).”

Boycott was left with “a great financial loss” and ultimately, the boycott was successful. And according to Bustle, “within 10 years, any business who somehow disappointed the Irish National Land League was quickly boycotted.”

The Ladies' Land League

After Parliament introduced the Protection of Persons and Property (Ireland) Act in January 1881, leaders of the Land League rightly suspected that they were soon to be arrested. In response, Michael Davitt suggested creating a Ladies’ Land League, “who would be able to take over the work of the League if the leaders were arrested,” writes the Michael Davitt Museum. According to the biography Michael Davitt, although his proposal was laughed at and rejected, he eventually got them to agree to “what they dreaded would be a most dangerous experiment.”

The idea for the Ladies Land League actually originated from Fanny Parnell, Charles Parnell’s sister. And when the Ladies Land League was founded by Fanny Parnell and her sister Anna Parnell in January 1881, it became “the first political organization in Ireland to be led and run by women.” When the men in the Land League were arrested, the Ladies Land League took over. They held public meetings, encouraging people to withhold rent and resist evictions, they provided evicted families with Land League wooden huts for shelter, and by the end of 1881, they had over 500 branches.

Although Charles Parnell initially appreciated the work of the Ladies Land League, “their efficiency and development caused upset amongst a number of the male League leaders” and in August 1882 the organization was dissolved.

What happened to Boycott?

After the soldiers started to leave with the harvesters, Charles Boycott realized that his time in County Mayo was also up. Boycott and his wife “quietly and sadly left their home in an army ambulance wagon” but before long, everyone was reporting on his flight. Meanwhile, his name had quickly become synonymous with “a campaign to bring down tyrants,” writes Irish Central.

And according to History of Yesterday, it crossed the Atlantic with him as well. When Boycott and his family visited the United States, the New York Tribune wrote about his arrival and the new word he inspired. The piece even noted that in an attempt to hide his identity, “Boycott had taken security measures, registering as Charles Cunningham.”

Boycott retained the Lough Mask House in County Mayo until 1886, but since his request for compensation for the losses sustained during “the absence of law in the West of Ireland” was denied, Boycott was forced to sell the house. Moving back to England, Boycott continued to work as a land agent until he died on June 19th, 1897, “a technical bankrupt.”

What happened to tenants in Ireland?

In August 1881, the United Kingdom passed the Land Law (Ireland) Act, which finally established the Three F’s that the Land League had been campaigning towards. According to “The Limits to Land Reform,” the 1881 Fair Rent Act “gave statutory basis to what amounted to a coproprietorship in Irish agricultural land: landlords had the right to draw an income from land, but tenants had limited property rights in the same land.” Unfortunately, even though power of the landlords was greatly reduced, “the rate of eviction remained high“

Although the leaders of the Land League were briefly arrested in late 1881, the resulting Kilmainham treaty is considered the end of the Land War. While Parnell was imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol, he told British Prime Minister William Gladstone that “if there was an abatement for tenant rent-arrears, he would work towards reconciliation” in Ireland. Gladstone agreed to Parnell’s terms, and the resulting Arrears of Rent (Ireland) Act 1882, which allowed cancellations of unpaid rent “up to $41.” As a result, $2.7 million worth of overdue back rent was cancelled (equivalent to $69 million today).

In 1882, Charles Parnell founded the Irish National League as a successor to the Land League. However, this organization expanded beyond abolishing landlords and became focused on establishing Irish Home Rule.

The legacy of boycotts

After the ostracization of Charles Boycott, boycotting spread across Ireland. However, not all of them maintained Parnell’s non-violent attitude. According to Irish Englishisms, in 1881, after Irish tenant farmer Peter Dempsey refused to leave his farm after the Land League asked him to, someone shot him dead. However, such violence was relatively rare. According to The Agricultural History Review, murder and manslaughter amounted to no more than 0.79 percent of “agrarian outrage.” Comparatively, threatening letters amounted to at least 50 percent of agrarian outrage.

The expression of boycotting soon spread like wildfire and by 1881, the word was even being used figuratively. Bustle writes that it only took eight years for the word “boycott” to find its way into the New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, also known as the Oxford English Dictionary. The word traveled through various languages and words like boykot in Armenian or boicottare in Italian all find their roots in a landlord’s henchman.

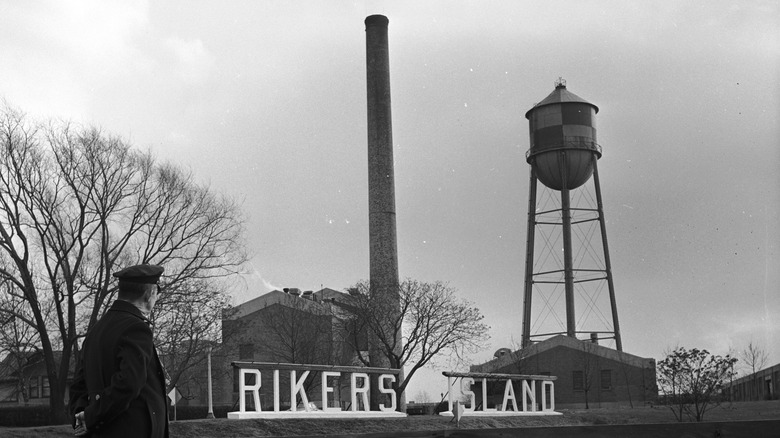

The Tragic Story Of The 1957 Rikers Island Airplane Crash

The Horrible Medieval Weapon That Was Used To Torture Wives

Why Some Believe The World Will End In 2100

The Eye-Opening Truth About Gwen Shamblin Lara's Religious Childhood

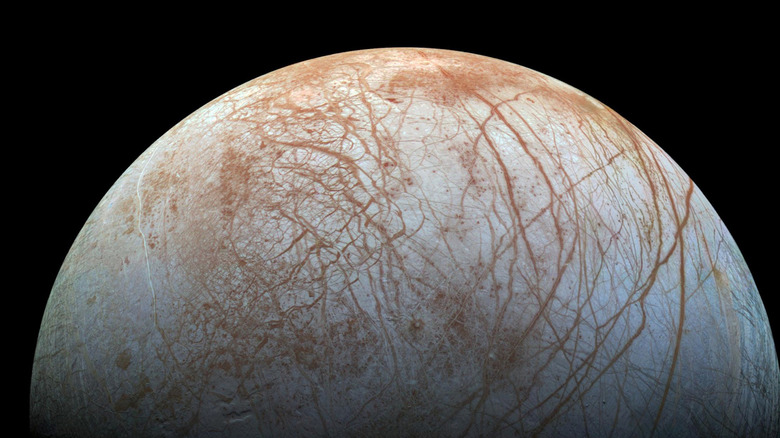

The Mystery Of Europa's Geysers

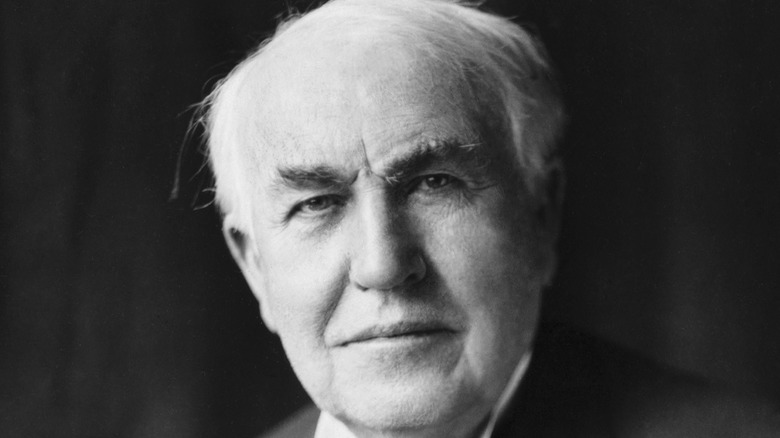

The Execution Device Thomas Edison Secretly Helped Finance

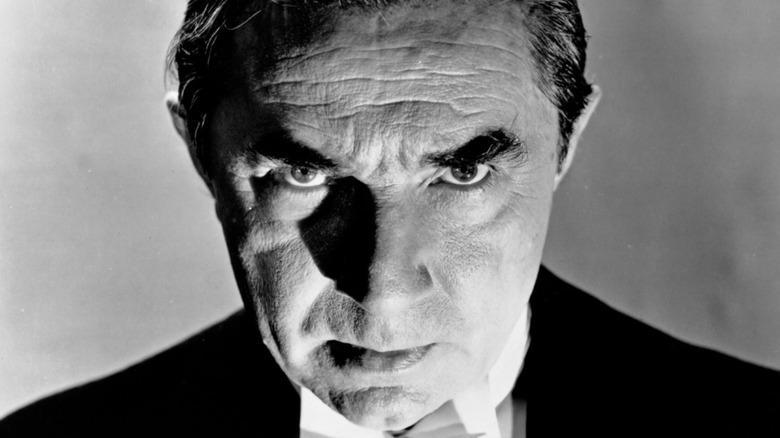

A Look At Bela Lugosi's Relationship With Boris Karloff

The Truth Behind Chicken Pox Parties

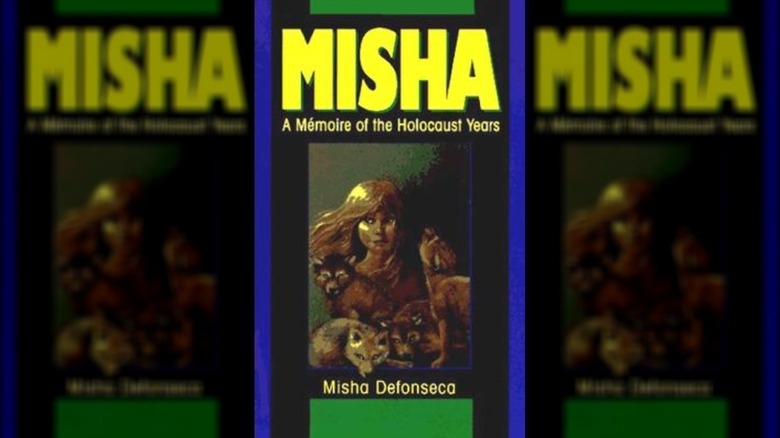

This Is How Fake Holocaust Survivor Misha Defonseca Was Caught

Whatever Happened To Sophie Toscan Du Plantier's Husband?