Here’s Why Anna Karenina Is Considered The Best Novel Of All Time

While there are definitely examples of fiction dating back thousands of years that could be considered novels, what we think of as a novel in the modern sense really only goes back a few centuries. Of course, when you start looking into the history of the novel, you quickly realize that this is an argument that can never be definitively settled, simply because people can’t even agree on what officially constitutes a novel.

If we can’t even nail down the definition, you might think it would be hopeless to figure out what the best novel ever written might be, and in a sense, you’d be right. Art is subjective, and you’ll never get 100% of humanity to agree on the greatest novel ever (or even read a novel in the first place). Plus, you’d always have that one joker that keeps voting for “Twilight.”

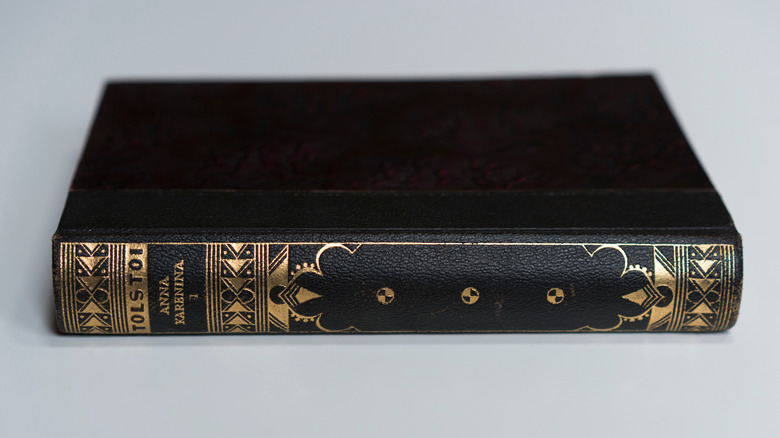

But if you leaf through the many, many discussions, articles, essays, and theses concerned with picking the best novel in history, you will find a short list of works that appear each and every time — and of those, one stands out: a novel that is always in the Top 5, if not the Top 3, if not No. 1. Here’s why “Anna Karenina” is considered the best novel of all time.

It begins with one of the greatest opening lines ever

The first line of “Anna Karenina” is deservedly famous — so famous that people are aware of it even if they’ve never read the book: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

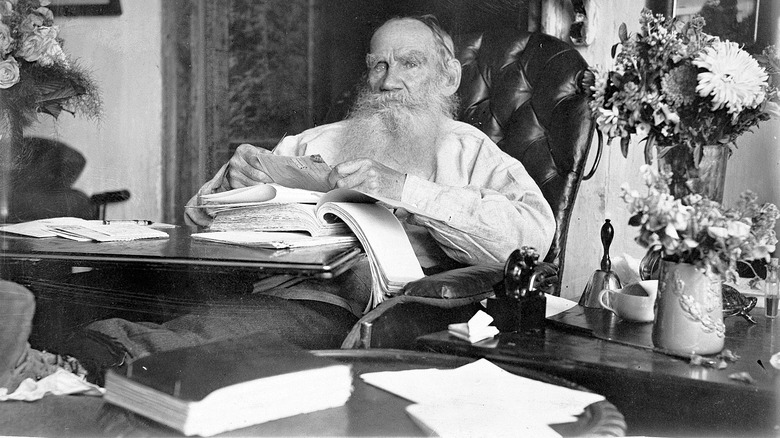

This is far more than simply a well-written line. It communicates an idea that immediately seems universal and obvious while setting up the fundamental philosophical lens we’ll experience the story through. The Conversation reports that Leo Tolstoy made this explicit in a conversation with his wife when he said, “In order for a book to be good, one has to love its basic, fundamental idea. Thus, in ‘Anna Karenina,’ I loved the idea of the family.”

As noted by Book Riot, the sentence is written in the present tense, while the story itself is told in the past tense, as if it’s the evidence supporting Tolstoy’s statement. The genius goes deeper, though, because there’s a subtle, implicit challenge: You can be happy and boring — all alike — or you can be miserable and interesting.

And yet, there are no truly happy families in the story. (Only one pair of characters achieve what could be described as a certain kind of happiness.) In other words, there’s a spoiler hidden in the first line, because happy families are all alike because they don’t actually exist.

Anna Karenina is the ultimate realist novel

Realism is a literary movement that evolved during the 19th century. According to Britannica, it sought to depict life accurately and objectively, portraying common people in everyday scenarios without artifice. That doesn’t necessarily mean a lack of symbolism or beautiful writing — it’s more about capturing the drama and beauty inherent in real life than inventing wild stories about exceptional people.

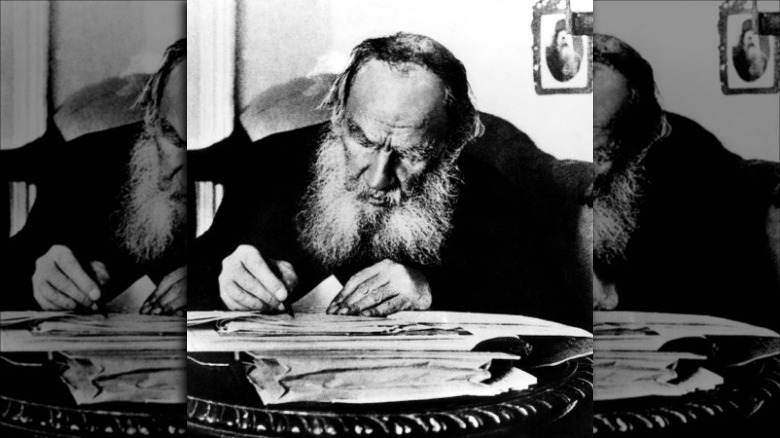

By the time Leo Tolstoy sat down to work on “Anna Karenina,” realism was a well-established movement. But Tolstoy perfected the technique. As critic James Meek points out, Tolstoy eschews metaphors and similes and simply tells the reader what things are, what characters are doing, in simple but beautiful language. He goes inside the heads of his characters and lets the reader know what they are thinking. There are no mysteries here. The use of both an omniscient narrator and a stream-of-consciousness approach to the characters’ inner lives effortlessly captures every detail.

As noted by author Debashish Sen, the realist approach in “Anna Karenina” extends to the narrator and the characters. Even though the reader is allowed into the private thoughts of the characters, the technique conveys the impression of simple truth-telling, that the narrator is simply reporting facts about people he knows intimately. That gives the characters and their motivations a timeless quality and makes all of their decisions — even when self-destructive — believable.

The characters feel incredibly real

It’s often said that modern audiences can’t appreciate how groundbreaking the film “Citizen Kane” is because the techniques it introduced or perfected have become common. The same can be said for “Anna Karenina.” Its characters feel extremely solid and real. Tolstoy achieves this remarkable effect through a variety of sophisticated techniques that are commonly used in modern fiction but were startlingly original in the late 1800s.

Author William Dalrymple notes that Tolstoy’s realistic approach results in characters whose personalities we recognize because they resemble people we’ve met or interacted with, even though the book is set in Imperialist Russia more than a century ago. Tolstoy also employed stream-of-consciousness writing (portraying the unvarnished thoughts of his characters) long before the technique was made famous by writers like James Joyce. Critic Gary Saul Morson points out that Tolstoy’s use of the device is so seamless that he even offers us the perspective of Levin’s dog, Laska, several times without disrupting his narrative — and Laska’s perspective is crucial to understanding her owner, Levin.

As James Meek notes, Tolstoy’s use of an omniscient narrator together with the characters’ internal monologue allows that narrator to subtly comment on their behavior and thoughts. And jumping between different perspectives gives us both subjective and objective views of the characters. We have so many sources of information about them, we are able to form a three-dimensional image of them just like we do in real life when observing the people around us.

Anna Karenina is surprisingly feminist

Being feminist in outlook doesn’t automatically make a novel great, but as noted by Britannica, the way Tolstoy explores the uneven playing field faced by women in 19th-century Russia was way ahead of its time.

Most obviously, Tolstoy carefully notes the tragic double standards faced by his characters. Author Jilly Cooper points out that the consequences of infidelity and sexuality are starkly different for the men and women in the novel: Anna’s brother has an affair with the nanny hired to care for his children but is forgiven. The man Anna has an affair with, Vronsky, suffers some minor embarrassment over their affair but remains wealthy and accepted by society. As explained by Book Riot, Anna has the opposite experience — she loses everything. She finds herself ostracized and powerless, she’s cut off from her beloved son, and she’s ultimately driven to suicide.

Tolstoy is careful to make his feminist themes a thread that runs throughout the novel. The characters argue about educating women, and Anna and other female characters suffer in large part because their lives are restricted to being wives and mothers. The novel’s famous scene involving Vronsky in a horse race can be seen as a metaphor for his relationship with Anna: Instead of letting the horse take charge, Vronsky imposes his will on it, with tragic results — for the horse. Vronsky walks away unscathed.

Its themes are incredibly complex

Telling people what “Anna Karenina” is about can be tricky. You can say it’s about love, the consequences of infidelity, the plight of women trapped in regimented, gendered roles, or how the modern world distorts our natural lives — and you’d be correct on all counts.

As Book Riot points out, part of the complexity of the novel’s themes is how Tolstoy misdirects us. For example, the only true love affair in the story has nothing to do with Anna and her love for Vronsky. True love is found in the slow-burn relationship between Kitty and Levin. Tolstoy contrasts the two relationships to make the point that Levin, who wishes a simpler, more natural life, is the better man, and thus the better lifestyle.

The New Yorker explains that Tolstoy’s novel isn’t just about infidelity or even love. It explores the consequences of our emotional attachments, both familial and romantic. A superficial reading of the novel sees Anna as a heroine, a woman who follows her heart and is willing to pay the ultimate price. A deeper look reveals Tolstoy’s true lesson: Love destroys. Nothing good comes of Anna’s quest for happiness. And as critic Gary Saul Morson notes, ignorance and a lack of education and experience are what doom Anna. She can’t predict the consequence of her actions because she’s working on a primitive, thoughtless level. And there are even more layers to Tolstoy’s themes, if you work to reveal them.

It's a novel of many interpretations

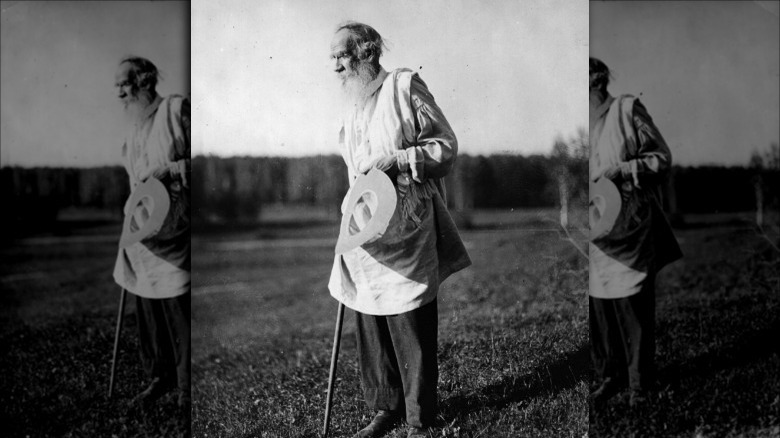

Tolstoy had some very definite ideas he wanted to communicate in “Anna Karenina.” He was going through a spiritual awakening, and his preference for a rural, simpler life versus the “artificial” life he saw in the cities is clear in the way he presents his characters and settings. As noted by critic James Meek, Tolstoy barely describes the urban settings in his novel, while the countryside is lavished with incredible detail, making the author’s preferences plain to see.

But one of the marks of genius in the novel is how different people come away with different interpretations. As The New Yorker notes, some see it as a love story, while others note that love is actually a destructive force in the book. For example, Commentary Magazine argues that Tolstoy’s real point is that the dramatic and exciting love we’re shown in other love stories is actually Anna’s downfall, while the patient, steady love that grows slowly and naturally between Levin and Kitty is nourishing and healthy. But as Inquiries Journal notes, the novel can just as easily be seen as a study of families and how they support — or fail to support — and sometimes smother their members.

“Anna Karenina” is a novel that can be interpreted in many different ways because it’s actually about all these things. Tolstoy somehow weaves together several philosophical discussions into a single novel.

It's sexy as heck

When faced with reading an enormous 19th-century novel written by a stoic Russian aristocrat who spent the last few decades of his life dressing like a peasant and arguing for chastity, you might think you’re about to be bored to tears. But “Anna Karenina,” like its author, is pretty lusty.

As James Meek makes clear, much of the novel is actually obsessed with sex, most obviously in Anna’s lust for Vronsky and its disastrous consequences. And Oprah’s Book Club describes the novel as “the ‘Harlequin Romance’ of its day.”

As critic Ronald D. LeBlanc notes, “Anna Karenina” is obsessed with sex and its consequences in large part because Tolstoy himself — a noted womanizer — was struggling with his own libido while writing it. While the book contains no overt sexual descriptions (this isn’t “Fifty Shades of Grey), sex soaks just about every page — even moments of disdain or hatred are defined by sex. Author Francine Prose points out the scene where Anna returns to her husband after meeting the handsome, virile, sexually exciting Vronsky and becomes obsessed with how unattractive her husband’s ears are. This is a woman who is suddenly lusting after a good-looking man, and that lust starts to affect how she sees the world around her.

Anna Karenina is a lot of fun

Somehow, despite tackling heavy themes like the destructive power of love or the corrupting influence of modernity, Tolstoy managed to make “Anna Karenina” a whole lot of fun. Tolstoy’s narrator is often arch and subtly sarcastic, as when he describes the trouble with finding suitable matches for women in Russian society: “The Russian fashion of matchmaking by the officer of intermediate persons was for some reason considered disgraceful; it was ridiculed by everyone … but how girls were to be married, and how parents were to marry them, no one knew.”

The book is full of sly humor, but it’s often subtle and takes some work to “get.” The New York Review, for example, notes how Tolstoy describes Lydia Ivanovna and her marriage: “Whenever the husband met the wife, he invariably behaved to her with the same venomous irony, the cause of which was incomprehensible.” The joke is, the cause is not incomprehensible at all: Lydia is an awful person, a moralizing hypocrite who hides her insults behind polite bible-thumping.

As noted by Prolific Living, Tolstoy is careful to offer us comic relief throughout, often via the character of Anna’s brother Oblonsky. Oblonsky is presented as a typical modern Russian man, and Tolstoy, who has nothing but contempt for modern Russian men, makes him a cluelessly happy blunderer whose inability to truly understand the world around him amuses the reader.

The story is perfectly paced

When people first encounter “Anna Karenina” they’re sometimes put off by its sheer length. Depending on the translation, the book can get pretty close to 1,000 pages. And yet, once you start reading, you barely notice how long the book is, because Tolstoy is a master of pacing.

As author Jilly Cooper notes, the novel was originally serialized. (According to Encyclopedia.com, it appeared in the periodical Ruskii Vestnik between 1873 and 1877 before being published as a novel in 1878.) That allowed Tolstoy to punctuate his story with numerous cliffhangers that make the reader want to keep reading to find out what happens.

Despite the title of the novel, Anna’s is just one of several stories being told within. Tolstoy uses the many subplots and minor characters he introduces to hold our interest — just as we might be getting irritated with Anna’s selfishness or bored with Levin’s philosophy, Tolstoy whisks us to another plotline. Oprah’s Book Club also notes how Tolstoy uses anticipation: Levin and Anna seem connected, and it’s natural to assume they will meet and affect each other. But they meet just twice in the story. Tolstoy uses this so the reader is always engaged.

Tolstoy uses repetition — and boredom — strategically

It might seem strange to praise a novel’s use of repetition and boredom. But that’s only because in most novels, repetition and boredom are accidents of bad writing. In “Anna Karenina,” Tolstoy uses both as tools.

One example noted by author Mohsin Hamid concerns Levin and his work in the fields. Many readers are confused by the lengthy passages describing Levin’s work on the farm side-by-side with peasants. These passages go on far longer than seems necessary to get their point across, but there are two reasons for their presence in the story. One, Tolstoy is writing a realistic novel, and he uses these passages to describe Levin and the world he inhabits through an incredibly dense exploration of detail — the world becomes real to us because Tolstoy gets down to almost a molecular level. And two, reading these repetitive passages recreates to some extent the meditative state Levin is in. Reading them, you become as hypnotized as he is by the labor he is performing.

Translator Marian Schwartz discusses another aspect of repetition in “Anna Karenina”: that of vocabulary. Historically, translators have regarded Tolstoy’s repeated use of certain words, often very close to each other in sentences and paragraphs, as a flaw, but, in fact, he did this to purposefully create links between characters via similar and repeated descriptions.

Tolstoy hides the deep dives

“Anna Karenina” is often misunderstood as simply a love story or a tragedy — albeit one crowded by a huge cast of characters and many philosophical digressions. But Tolstoy crowds his story on purpose, because he uses the relatively straightforward aspects to mask the bigger questions he’s asking.

The New Yorker notes how the reading experience of the novel shifts as you grow older, because Tolstoy isn’t really writing a love story. The deeper dive is that he’s exploring the effect that emotion can have on our lives. Penguin Classics discusses how Tolstoy uses the character of Levin not just as a contrast to both Vronsky and Anna and their selfish passion. The deeper dive is how Levin acts as a stand-in for Tolstoy’s examination of faith and spirituality.

Similarly, no one ever describes “Anna Karenina” as a book about suffering, but the deeper dive is that it is a book about suffering hidden behind stories about love. Its famous first line (“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”) makes this clear with its implied focus on unhappy families. But as The Guardian notes, the universe of “Anna Karenina” isn’t necessarily a fair one — many characters are unfaithful or commit crimes in the novel, but only Anna is actually punished. Tolstoy’s ultimate question is why some acts of love and passion lead to suffering and some don’t.

Anna Karenina is actually two novels in one

Leo Tolstoy was a masterful writer. One of his greatest achievements was the way he utilized parallel plots in “Anna Karenina” to fully explore his themes. There are two stories being told: one starring Anna Karenina, urban society woman, and one starring Konstantin Levin, old-school country aristocrat. Both seek meaning in their lives, but Anna seeks it through passion while Levin seeks it through spiritual contemplation.

The Conversation notes how Tolstoy cleverly sets up the connection between Levin and Anna through Stiva Oblonsky, Anna’s brother and Levin’s best friend. This connection gives the reader the impression that the two characters are very close, in the same circles — yet their parallel stories demonstrate the opposite. Oprah’s Book Club observes how the story seems to promise that Anna and Levin will meet and that it will be a powerful moment, but they meet just twice in the story, because they are actually growing further apart as the novel progresses, not closer together.

The end result is two novels in one: Anna’s descent into punishment and suffering as she struggles against a loveless marriage and society’s unfairness, and Levin’s ascent into spiritual peace and a loving relationship as he surrenders to a higher purpose. The two stories only seem like one because of the many connections the characters in each share.

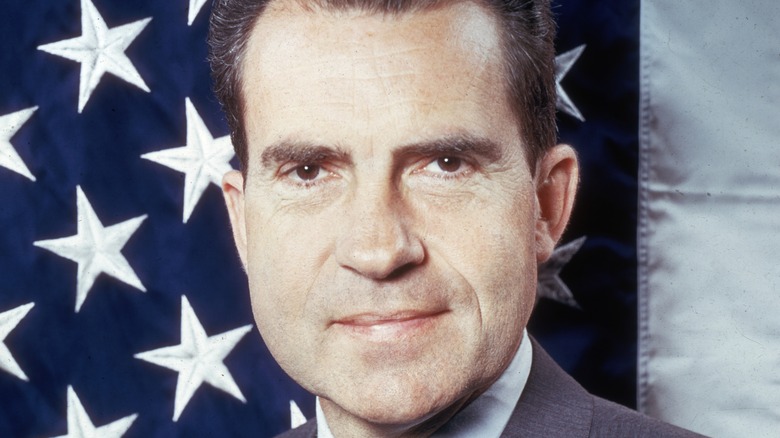

Nixon's Alleged Plot To Assassinate A Journalist Explained

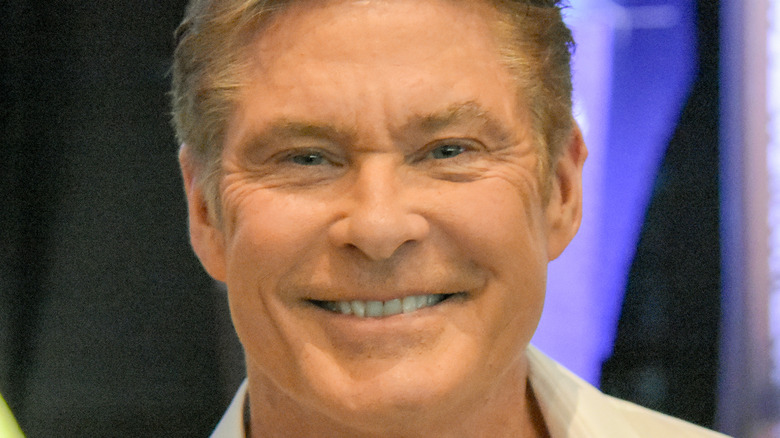

How David Hasselhoff Is Connected To The Fall Of The Berlin Wall

The Biggest Gabrielle Petito Theories: What Really Happened?

The Dark History Of Poena Cullei Execution

The Truth About The Deadly Tenerife Airport Disaster

Inside The Time Steve Irwin Saved His Best Friend From A Crocodile

Everything We Know About Queen Elizabeth's Platinum Jubilee So Far

What You Should Know About Secret Service Earpieces

The Shady Truth About Joss Whedon

The Devastating Death Of Mister Rogers' Wife, Joanne Rogers