Messed Up Things That Happened During The Mexican-American War

The Mexican-American War was fought between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848, and it’s a conflict hardly anyone remembers, even though it’s actually pretty important. The war began over the issue of the U.S. expanding its territory as well as the debate over slavery, and it ended up being the prologue to another, much more remembered war. Whenever a new state entered the U.S., it needed to be decided whether it was a slave or free state, and tensions over the territory won from Mexico after the war contributed to the Civil War. In addition, several famous Civil War generals fought in the Mexican-American War, as well as future president Zachary Taylor.

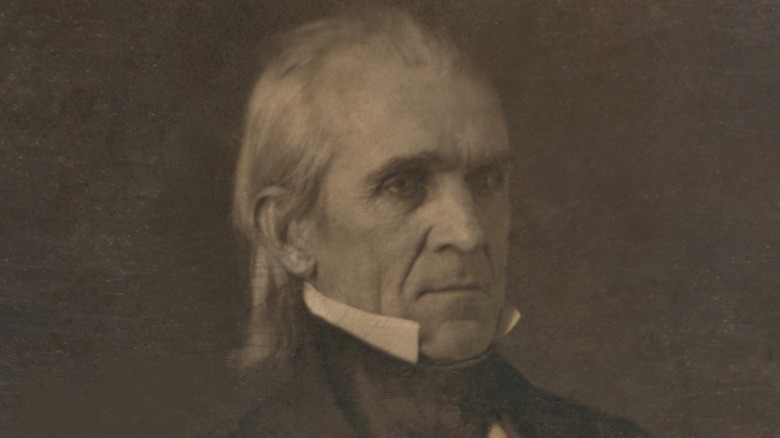

The war was hardly a fair fight, as President James K. Polk deliberately provoked Mexico into the conflict, and the U.S. Army was much better-equipped. Plenty of messed-up things happened both on the battlefield and off, including how the diplomat who negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war, was fired right after, writes the National Constitution Center.

The Mexican-American War ended up being a boon for the U.S., since it gained the country its entire Southwest as territory. Mexico, meanwhile, lost over half of its land. The U.S. also reneged on what was agreed to regarding rights of native Mexicans once their land became part of the United States. Here’s some of the crazy stuff that happened during the Mexican-American War.

When Polk's offer was rejected, he invaded

President James K. Polk, along with many of his countrymen, thought the U.S. had a “manifest destiny” to spread from coast to coast, writes History. At the beginning of 1846, America didn’t stretch that far, but it soon would.

Texas had gained its independence from Mexico in 1836. Due to the slavery debate, Texas was not added to the Union immediately because that would ensure a discussion of whether it would be slave state or a free one. Mexico also threatened to make war on the U.S. if they made any move to claim Texas for their own.

Polk was popular in the 1844 election due to his stance on expansionism: He supported acquiring and occupying both Texas and Oregon, causes popular in the South and North, respectively, writes the White House. In 1845, Texas finally joined the Union as a state, which Mexico considered an act of war. The next year, Polk offered to purchase much of what is today the American Southwest from Mexico. He’d come into office with a series of policy goals, and he meant to accomplish everything he’d set out to. In this case, that meant by way of invasion. When Mexico refused, he had soldiers moved into a disputed zone along the Rio Grande, forcing Mexico to send their soldiers on the attack.

Camp followers risked their lives

During the Mexican-American War, women who followed the armies and lent their skills to cooking, doing laundry, treating the wounded, and more were called camp followers. Wives of enlisted U.S. soldiers were allowed to follow the men as cooks and laundresses, and the Army paid for four laundresses per company.

María Josefa Zozoya was one such camp follower from Mexico during the Battle of Monterrey, bringing food and water and providing medical care to soldiers on both sides. While doing so, binding a soldier’s wounds with her handkerchief, she was killed by gunfire, writes the National Parks Service. U.S. soldiers praised her compassion and humanity and called her the “Maid of Monterrey.”

Similarly, Sarah Bowman of the U.S. was nearly killed when a bullet passed through her sunbonnet while she was serving food and water during the siege of Fort Texas. Though camp followers were ordered to stay low to avoid getting shot, Bowman refused and continued her work. She was given an honorary military rank for her efforts and also buried with full military honors. Though the U.S. Army did not allow women to fight in the 1840s, the camp followers still proved their worth.

Santa Anna double-crossed Polk

Since American soldiers were in the disputed zone along the Rio Grande, Mexican cavalry fought them, losing the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de La Palma but causing the United States Congress to declare war on May 12, 1846. Mexico never issued a declaration of war against the U.S.

American generals were easily able to conquer the parts of Mexico that were north of the Rio Grande, writes History, particularly since so few people actually lived there, and then they advanced south. Zachary Taylor was able to capture Monterrey in September 1846. Mexico asked General Antonio López de Santa Anna, who was living in Cuba at the time, for help with the ever-worsening war. Santa Anna managed to convince President Polk that he would work things out favorably for the U.S. when he went to Mexico. However, he instead led the Mexican army full speed ahead into the war, firmly against the Americans.

In February 1847, the Battle of Buena Vista occurred, leading to heavy losses for General Santa Anna, but he took up the presidency of Mexico that March. In the meantime, U.S. general Winfield Scott took the city of Veracruz. By September, Scott was laying siege to Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle.

Mexican military cadets committed suicide rather than surrender

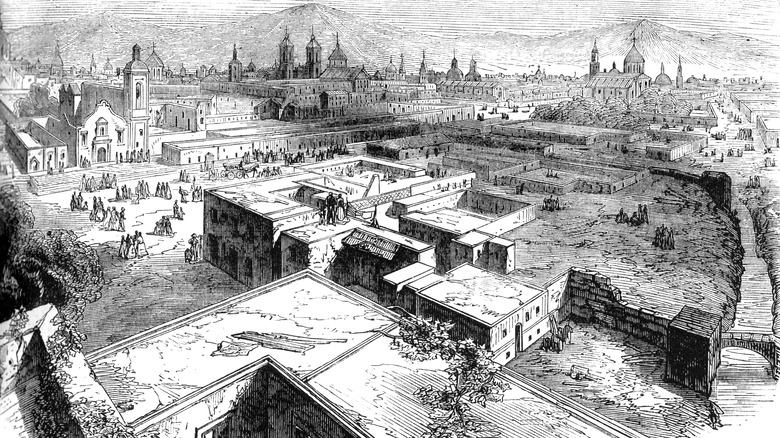

American general Winfield Scott laid siege to Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City in September 1847, having marched there with his army from Veracruz, which they’d captured, writes History. There, a group of military school cadets reportedly committed suicide rather than give themselves up to the Americans. Chapultepec Castle was a strategic area to hold, since it protected Mexico City on its west side.

The six cadets are now known as Los Niños Héroes. These young men were between 13 and 19. Since Chapultepec Castle was in use as Mexico’s military training academy, dozens of cadets were at the siege. General Nicolas Bravo ordered everyone to retreat on seeing the Americans’ large numbers. Six young men, however, refused and stayed to fight the Americans. These cadets were Juan de la Barrera, Juan Escutia, Francisco Marquez, Agustin Melgar, Fernando Montes de Oca, and Vicente Suarez.

U.S. president Harry Truman visited the monument to Los Niños Héroes at Chapultepec Park (pictured) in 1947 and told reporters, “Brave men don’t belong to any one country. I respect bravery wherever I see it,” when asked why he’d come.

Indigenous peoples in ceded territories were worse off afterward

After Mexico gained its independence from Spain, it affirmed that native Mexicans were full citizens and had a right to their land, writes Native American Netroots. It was thought that erasing caste distinctions would help undo Spain’s history of paternalism. Each Mexican state, however, ended up deciding for itself how to handle native Mexicans.

Though Mexico won many concessions from the U.S. in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, affirming that native Mexicans (now Americans) would continue to have the right to their land after the war, indigenous people (as well as Africans) who lived in the territories Mexico gave up had it worse than before. White settlers flocked to these new lands, often forcibly displacing the indigenous people who lived there. In California in particular, many Native Americans lost their land.

As Navajo historian Jennifer Denetdale put it: “Ironically, the American rationale for claiming these lands was to bring peace and stability to the region, but the United States only escalated the cycles of violence among Navajos, other Native peoples, and New Mexicans.”

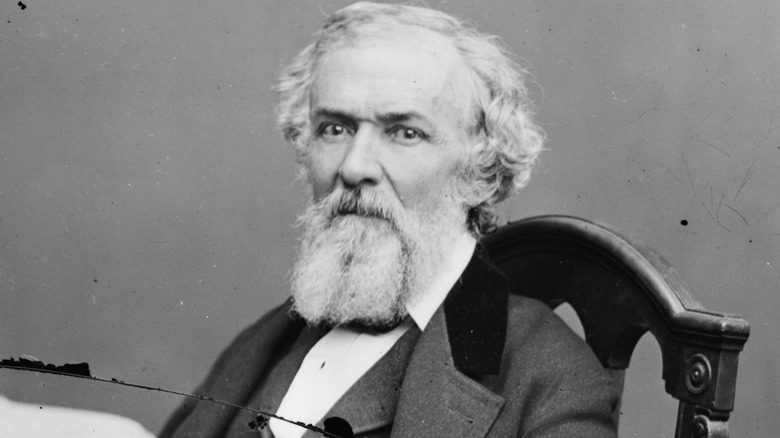

The Mexican-American War was the precursor to the American Civil War

American abolitionists feared the war was simply a way to bring more slave states to the union, while those in favor simply thought of it as the expansion of manifest destiny and white supremacy, writes the National Park Service. The Mexican-American War was the precursor to the American Civil War: Over the next decade, the question of whether the eventual U.S. states acquired from Mexico should be slave states or free came up again and again — and led to further bloodshed during the Civil War.

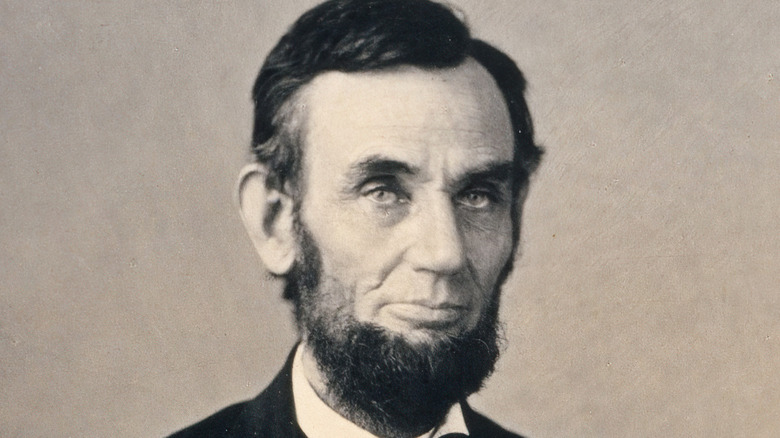

Several leading intellectuals and politicians opposed the war, including Abraham Lincoln, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Walt Whitman. In the years afterward, the slavery debate was occupied by accepting the territory from Mexico into the U.S. as states. The Compromise of 1850, which brought California into the Union, held off the Civil War by another decade, writes the American Battlefield Trust.

Ulysses Grant saw the Civil War as a direct result of the Mexican-American War, writing in his memoirs (via America’s Quarterly): “(The) Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war. Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times.”

The Mexican-American War was relatively small but lethal

Compared to other wars, the Mexican-American War was short and small. That said, 90,000 Americans were involved, with 14,000 dead, amounting to a 15.5% death rate, the highest of any foreign war the U.S. has been involved in, according to the Peace History Society. Meanwhile, the Mexican army was inferior and knew this was a war they couldn’t win. Approximately 25,000 Mexican soldiers died in the war.

U.S. soldiers stayed in Mexico from May 1846 until July 1848. One out of seven fatalities occurred either in battle or from battle-related wounds, while the other six were due to disease or other reasons. When President Santa Anna was routed by General Winfield Scott in late 1847, he fled Mexico City, essentially taking the Mexican military out of the war. Though it would be months before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed and the war was officially over, the Mexican-American War was effectively over from that moment, writes How Stuff Works.

A diplomat ended the war and was fired

Diplomat Nicholas Trist, chief clerk to Secretary of State James Buchanan, was sent to Mexico in April 1847 when it became obvious that the Americans were winning. After Mexico City was taken, Trist negotiated the peace talks with three diplomats from Mexico’s government. He was recalled by President Polk, who wanted to work solely in Washington, according to the National Constitution Center, but refused to leave, feeling he was close to a breakthrough.

Trist’s treaty allowed the U.S. to purchase what is now the American Southwest for $15 million. When the treaty was signed in February 1848, President Polk had no knowledge of it. He’d actually wanted even more of Mexico’s land (specifically Baja California and land east of it) but chose to accept it as written, and the treaty passed the Senate by a vote of 34-14. When Trist returned, however, he was fired. His political career had ended, and he spent the rest of his life working office jobs, only receiving back pay for the war in 1871.

In a letter to his wife in December 1847, Trist wrote, “Knowing it to be the very last chance and impressed with the dreadful consequences to our country which cannot fail to attend the loss of that chance, I decided today at noon to attempt to make a treaty; the decision is altogether my own” (via Our Documents).

Mexico's size was cut by more than half

Mexico gave up 55% of its territory in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and recognized the Rio Grande river as the U.S.-Mexico border. The ceded territory included parts of present-day Arizona, California, Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, and Nevada, writes the U.S. National Archives. Mexico gave up all claims on Texas.

The United States also agreed to pay debts owed to American citizens by the Mexican government, and the treaty included the protection of rights for Mexican nationals now living under U.S. law. After the treaty was accepted by the Senate, American troops withdrew from Mexico City. Four men were appointed, two by each government, to survey and set the new boundary, and an additional 47 border markers were added after the original six. Most markers were stone piles, though a few had inscriptions on them. In the 1880s, a boundary commission was created to remark the border.

Mexican officers were inept

General Antonio López de Santa Anna turned out to be incredibly inept, especially when compared with American generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. The U.S. also had better weapons, especially their artillery, which was the best in the world at the time. The American cannons had double the range as the Mexican army’s, writes ThoughtCo. The American technique of “flying artillery,” employing light, mobile mortars and cannons, made its debut in the Battle of Palo Alto.

The war marked the first time West Point-trained officers actually saw direct action, and they performed well. Mexico’s military and political leaders were in the middle of their own chaos at that time, which made their war effort messy and ineffective. Santa Anna and another general, Gabriel Victoria, despised each other and deliberately made military mistakes to make the other fail. Politics was similar, as the Mexican presidency changed hands several times over the course of the war.

Communication in general was broken among the Mexicans. Troops were rarely paid or given ammunition, and local governments refused to work with the central government. Mexico was also broke and dealing with rebellions across the country at the time. Overall, the U.S. was better-organized and better-prepared.

Conditions in general were terrible

Thousands in the U.S. Army died due to diseases during the war, primarily dysentery and yellow fever. Pollution and a lack of hygiene in the Army camps were the main reasons disease was so bad, not to mention the poor state of military hospitals in the 1840s, writes researcher Vincent J. Cirillo.

Yellow fever ran rampant in the Army, causing General Winfield Scott in particular no small amount of alarm. A fifth of patients struck with the disease died, writes David Tschanz for Montana State University, developing fevers, chills, and vomiting as their skin turned yellow from liver damage. Blood was cut off from their organs, and their lungs began to fill with blood. There was no cure or known cause.

When General Scott marched on Veracruz, one major part of his strategy was striking in the winter, thus hopefully avoiding the yellow fever season. However, the War Department caused a delay of several months by sending soldiers to the wrong places, and an outbreak of smallpox didn’t help, either. In March 1847, Scott completed his amphibious landing on Veracruz, the first in U.S. history, which was successful.

A measure to ban slavery in acquired land failed

Shortly after the start of the Mexican-American War, Pennsylvania Democrat David Wilmot introduced the Wilmot Proviso to Congress, which would ban slavery in any territories acquired from Mexico after the war. It failed to pass but ignited the slavery debate which ultimately led to the American Civil War, according to Britannica. The Senate was dominated by Southerners, and so it’s not surprising that the Wilmot Proviso was blocked, according to History.

The furor stirred up by the proviso also led to the creation of the Republican party in 1854. Northern Democrats were against Polk for conceding to Great Britain on the subject of Oregon’s border and gaining less territory than they’d wanted.

However, the Wilmot Proviso passed in the House of Representatives due to an alliance between Northern Democrats and Whigs. This marks the first shift in U.S. politics from alliances by party to alliances by region of the country, writes the American Battlefield Trust. Thus, the seeds of the Civil War between North and South continued to grow.

How Pluto Got Its Name

Here's Why Benjamin Franklin Wanted To Change The Alphabet

The Surprising Time The US Tried To Invade New Zealand

Why The Mayans Painted Human Sacrifices Blue

The Twisted Truth About The Dark Lord Of Rome

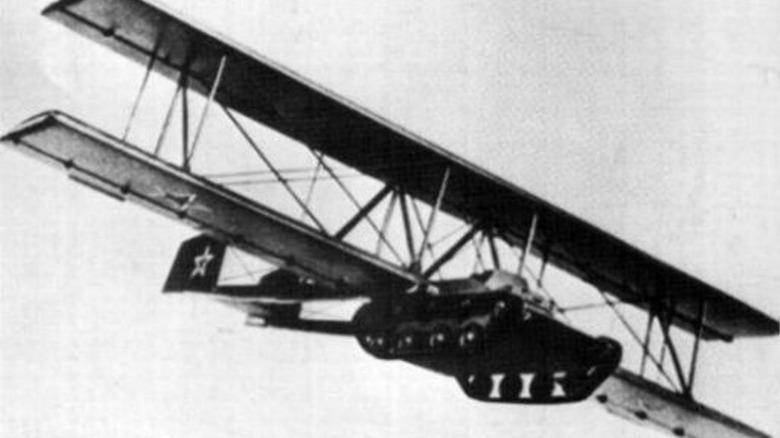

Inside The Soviet Union's Failed Flying Tanks

What Life Was Like As An Apothecary In The Colonial Era

Out Of Every Led Zeppelin Song, One Stands Above The Rest

The Myth About Pocahontas You Need To Stop Believing

A Look At Ponce De Leon's Feud With Christopher Columbus' Son