The Ancient Legend Of The Will-O’-The-Wisp

“… A wandring Fire / Compact of unctuous vapor, which the Night / Condenses, and the cold invirons round / Kindl’d through agitation to a Flame / Which oft, they say, some evil Spirit attends / Hovering and blazing with delusive Light / Misleads th’ amaz’d Night-wanderer from his way / To Boggs and Mires, & oft through Pond or Poole / There swallow’d up and lost…”

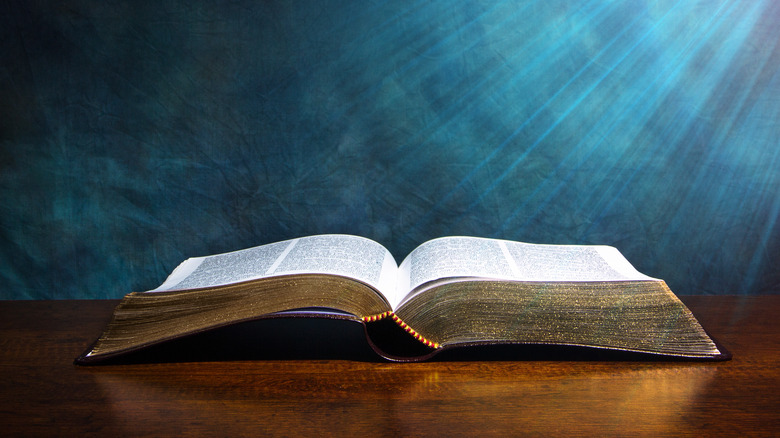

This gorgeously phrased, fanciful passage from Book VIII of John Milton’s monumental, 1663 epic poem “Paradise Lost” (available in full on Project Gutenberg) shows exactly how well-known will-o’-the-wisp folklore had become by the 17th century. In Milton’s poem — a very sincerely written, very dire fictionalized account of the Biblical fall of humanity to sin — he uses will-o’-the-wisps as shorthand for the story of the temptation of Eve from Genesis, chapter 3 (on Bible Gateway). She was wooed off course, lured by the allure of a bright-shining promise that fell further and further away, and in the end, found doom.

Found in “bogs and mires,” as Milton put it, bluish-white will-o’-the-wisps hover in the night above the muck and always seem to move out of reach. Back in 1563’s “Book of Meteors,” William Fulke described them as “ignis fatuus,” the “‘foolish fire’ that hurteth not,” as the Royal Publishing Society cites. This evolved into a synecdoche for chased illusions, false dreams, untrue hopes, naïve beliefs, and subversive danger. In the end, though? They’re not the byproduct of malicious spirits but simple chemical reactions.

A foolish fire turned Halloween pumpkin light

The legend makes sense, though, doesn’t it? Folks tracking through the soppingly soft soil of swamps and bogs under starlight, easily lost and confused, pushing through the forked fingers of leafless branches? People definitely died in such bogs, and cautionary tales developed similar to “fata morgana” — ocean-bound mirages that hover above the horizon.

“We are beginning to believe Magdala to be a fata morgana, an ignis fatuus, which gets more and more distant the nearer we approach it,” G.A. Henty wrote in 1868’s “The March to Magdala” (on Project Gutenberg). “Never did a geographical entity seem so to play the ignis fatuus with the world as did the [Columbia] River,” William Denison Lyman wrote in 1909 (also on Project Gutenberg). Per The Royal Society Publishing, the first recorded instance of will-o’-the-wisps goes back to 14th century Welsh poet Dafydd ap Gwilym, who in 1340 called them “canwyll corff” (“corpse-candles”). “There was in every hollow a hundred wrymouthed wisps,” he wrote.

This connection between lit skulls and will-o’-the-wisps lived on in the British Isles by its alternative name, “Jack-o’-lantern,” as Ripley’s explains. By Irish lore, Stingy Jack was a rapscallion who tricked the devil into paying his bar tab. When he died, neither heaven nor hell wanted him, so the devil gave him a single ember to place in a carved-out turnip to guide his forever-roaming soul: the will-o’-the-wisp. Remember this the next time you carve a Halloween pumpkin with your kid.

Dancing flames of methane-based chemiluminescence

The dancing flames of will-o’-the-wisps resemble other natural phenomena. The most obvious resemblance is seen in the bioluminescence of insects like fireflies, who produce their glow through the interaction of the enzyme luciferase and magnesium-adenosine triphosphate (ATP), per Pestworld. Firedamp is another potential culprit: flammable methane generated by coal seams, as Britannica explains. Then there’s St. Elmo’s Fire, which is a coronal electric discharge caused by superheated gas — plasma — passing through electric fields. Per Live Science, this causes nearby excited particles to lose energy in the form of photons, i.e. light. Ball lightning, similar to St. Elmo’s Fire, occurs near ground struck by lightning when vaporized elements interact with ionized air, as National Geographic explains. None of these phenomena look quite like will-o’-the-wisps, though.

The Royal Society Publishing has the best explanation, centered on gas bubbles rising from the “stagnant pools of rotting vegetable matter” of decomposing marshes full of anaerobic bacteria. This gas, typically comprised of two-thirds methane and one-third carbon dioxide, intermingles with the highly flammable phosphine gas generated by other, putrefying organic matter. Under certain conditions, this volatile cocktail more or less becomes “spontaneously flammable.” Whether fueled for a flashing instant or long enough to look like it’s hovering in place, this is the likely cause of will-o’-the-wisps.

That being said, there have been fewer and fewer sightings of will-o’-the-wisps in recent decades, making it difficult to get 100% proof-positive readings. Perhaps Stingy Jack just got bored of trying to lure victims to their deaths.

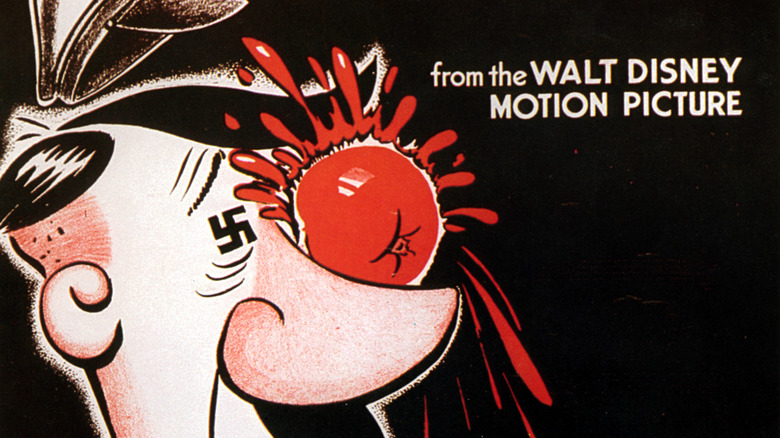

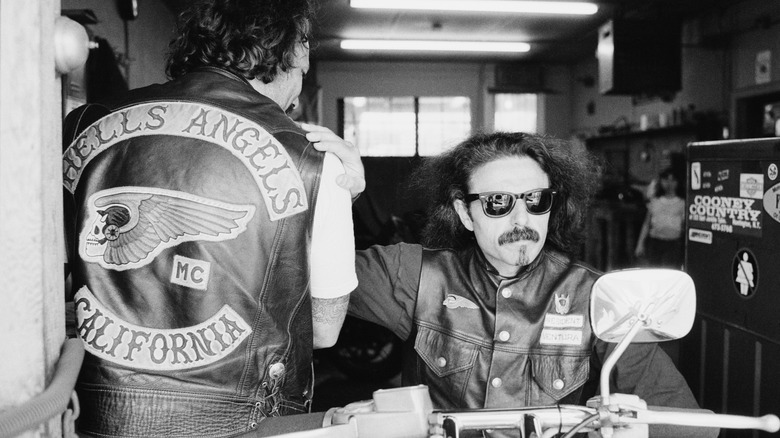

The Hells Angels Once Sued Disney. Here's Why

Here's What We Know About The Newly Identified 9/11 Victims

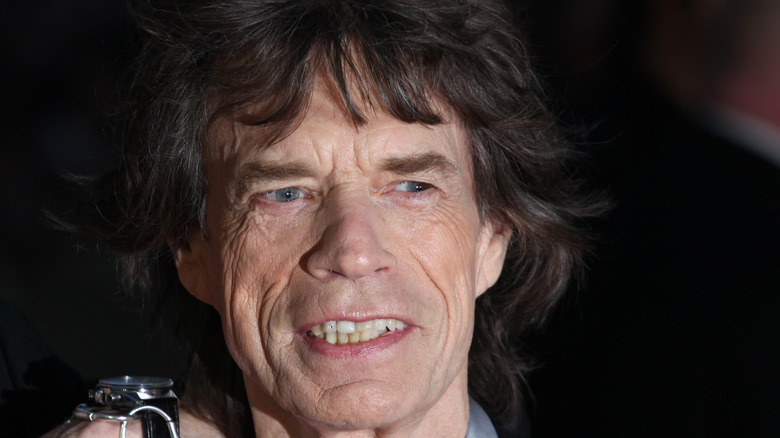

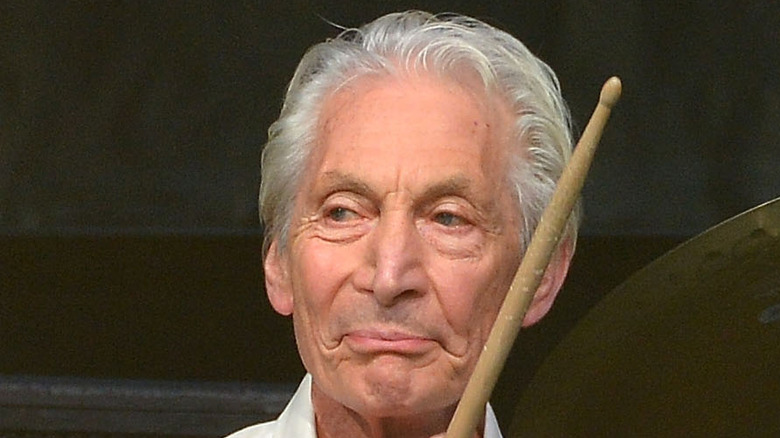

The Heart-Wrenching Death Of The Rolling Stones' Charlie Watts

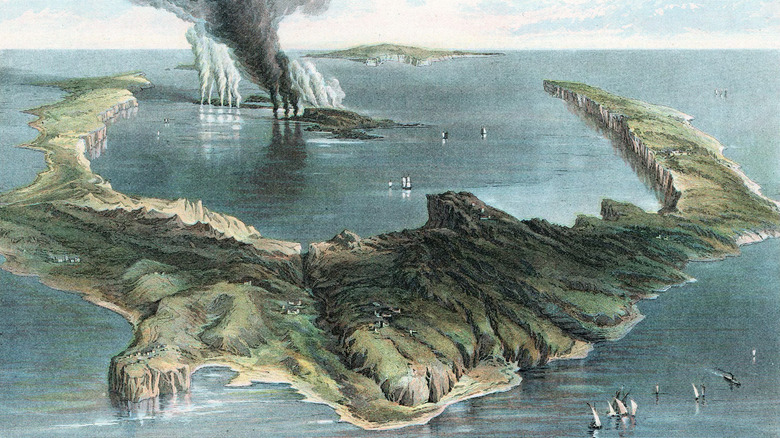

Atlantis-Inspired Myths That Turned Out To Be True

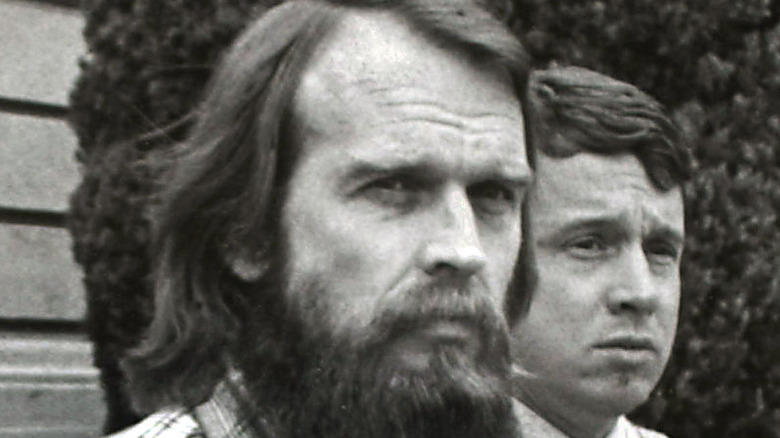

The Messed Up Truth About Cult Leader Ron Lafferty

The Untold Truth Of The Everly Brothers

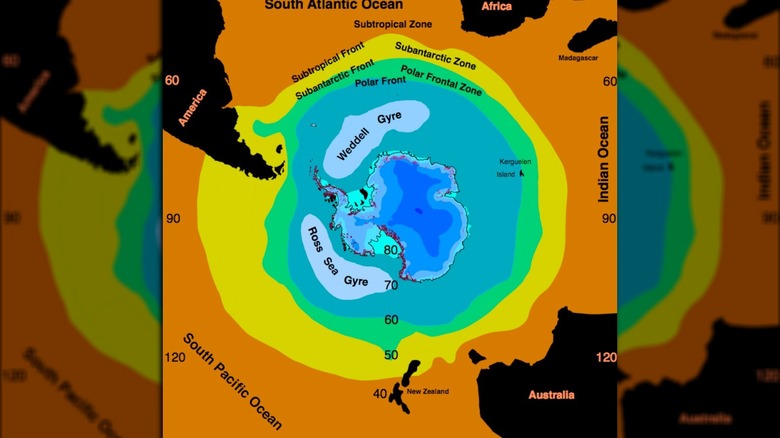

The Truth About The World's Fifth Official Ocean

The Mysterious Murder Of Dorothy Jane Scott

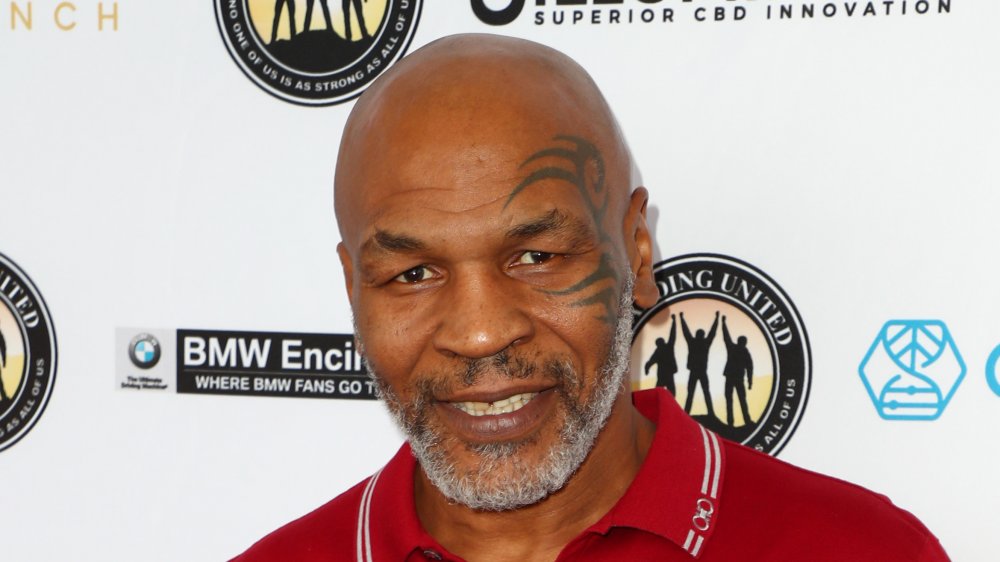

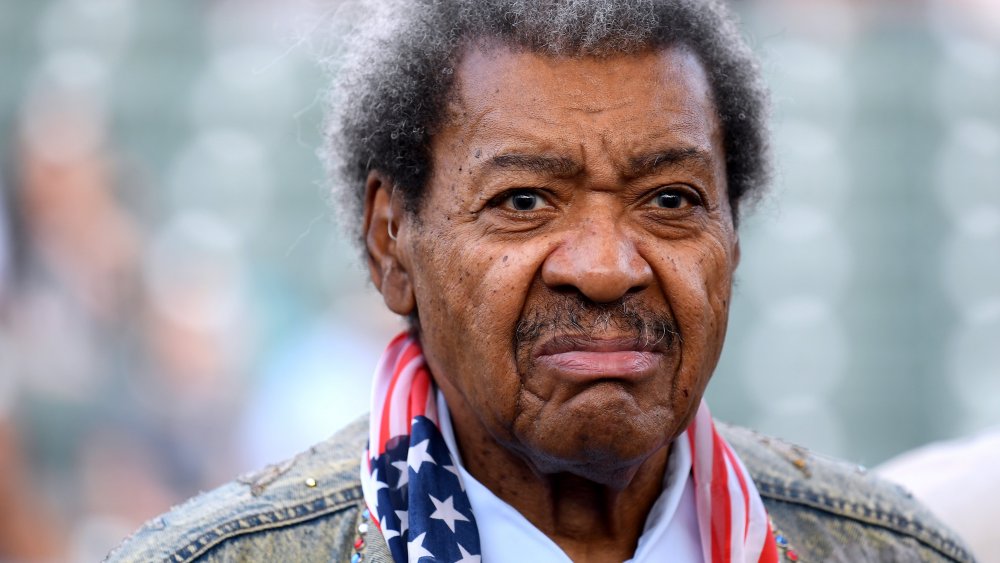

The Real Reason Don King Sued ESPN

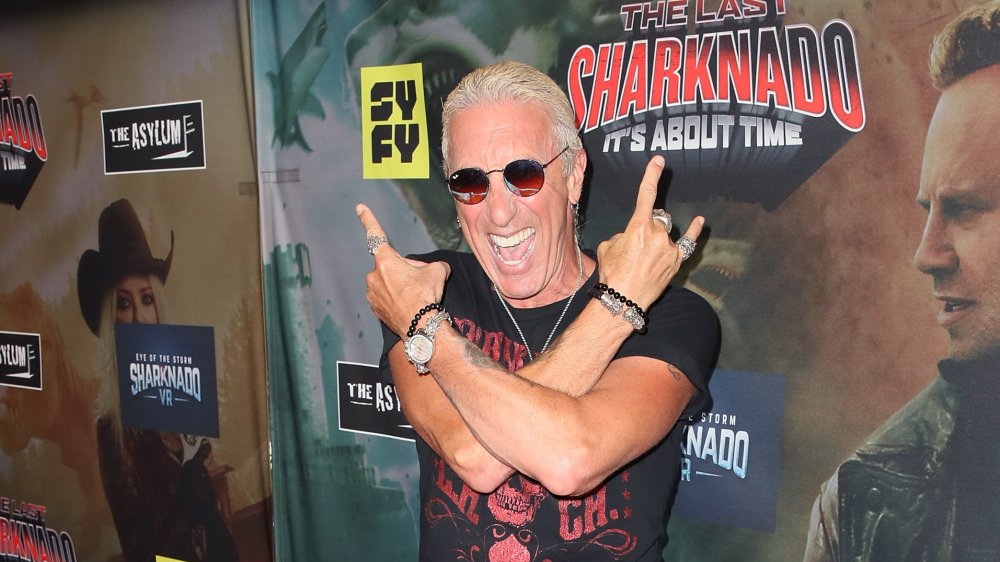

How Twisted Sister's Dee Snider Lost All His Money