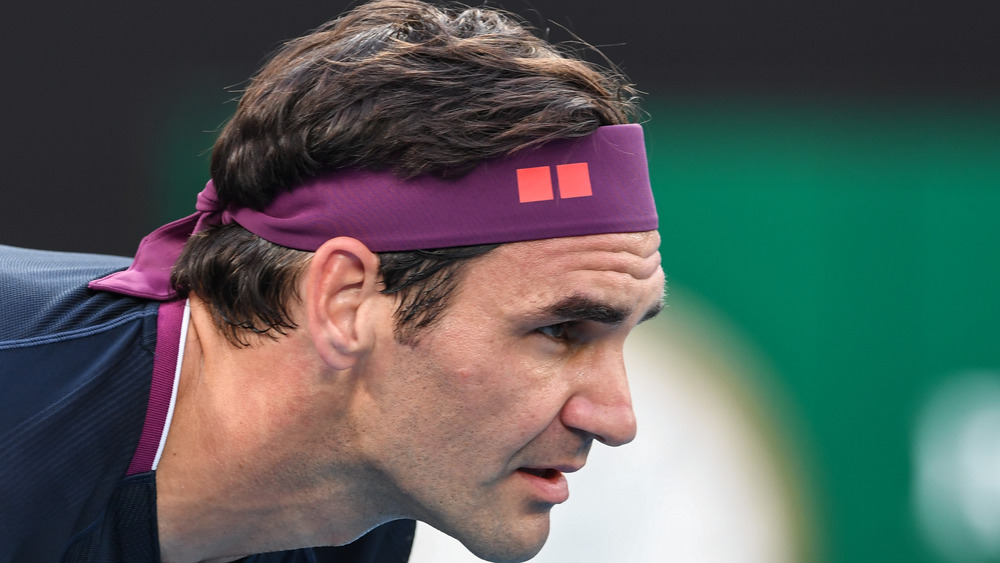

The Crazy Real-Life Story Of Andy Warhol

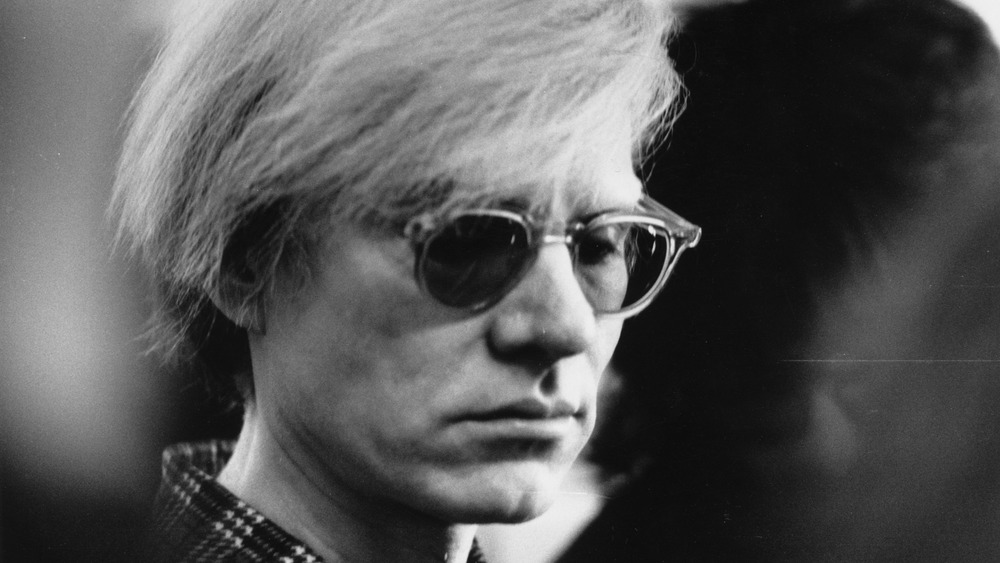

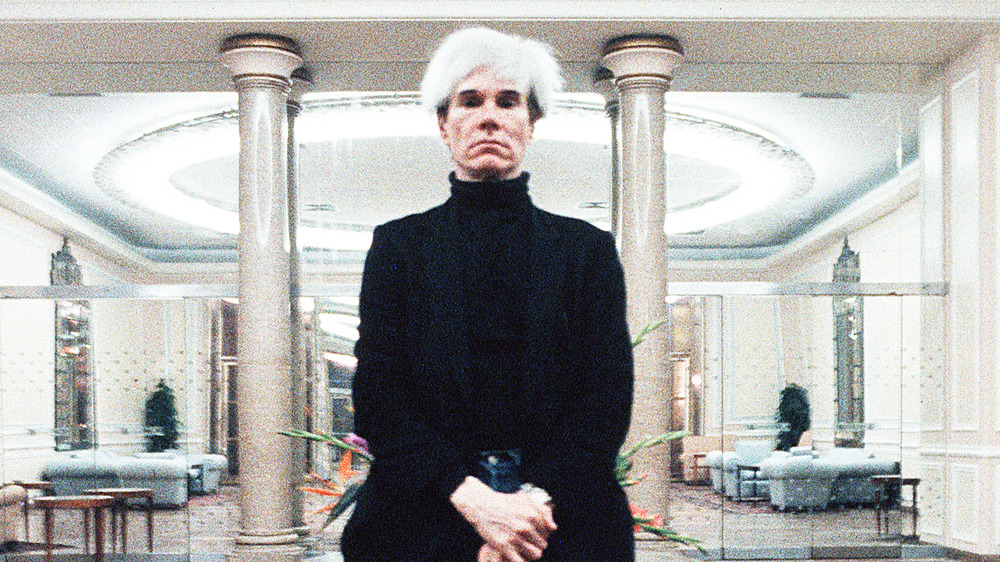

Controversial and enigmatic, Andy Warhol was one of the most important artists of the 20th century. Arguably, there is no other artist who so embraced and reflected the zeitgeist of the modern era. Beginning his career as a commercial artist, Warhol instinctively and consciously blurred the lines between art and commerce as well as good taste and bad.

Transfiguring product logos and celebrity images into works that both commented on the banality of consumer culture and celebrated its uniquely American qualities, Andy Warhol, with his famous, screen-printed soup cans and garish movie star portraits, redefined fine art for a generation. Through his Factory studio, he even changed the artist’s role in creation, employing assistants to manufacture his works on a virtual assembly line.

Painting was just one component of Warhol’s overarching artistic philosophy. As a filmmaker, he stripped the medium of its reliance on narrative and reintroduced pure abstraction to cinema. Warhol understood that the moving image, much like music, needed no plot to engage the audience’s emotions.

From photography to music, art was its own reason for being to Andy Warhol. Still, Warhol knew the arts were a way to make money, and he never shied away from the fact that he was engaged in a business — much to the annoyance of his more high-minded detractors. Andy Warhol’s wealth and fame, as well as those concepts in general, were just palettes with which to create. Above all, Andy Warhol was an American original. This is his crazy real-life story.

Andy Warhol's childhood shaped his future

Born Andrew Warhola in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on August 6, 1928, Andy Warhol was the third son of Ondrej and Julia Warhola. Immigrants from a small village in Slovakia, the Warholas were working-class people in search of a better life in the United States.

As detailed in Warhol by Eric Shanes, the Great Depression financially devastated the family. Yet, the resourceful Ondrej kept his struggling family afloat. By 1934, he was working as a construction worker and bringing in enough money to move his wife and children to a slightly more respectable neighborhood.

Young Andy Warhol’s talent was apparent upon his entry to elementary school, and by the age of nine, he was taking art classes at the Carnegie Institute Museum of Art. Warhol thrived at the Carnegie Institute, and the exposure to Pittsburgh’s wealthier denizens introduced him to a lifestyle markedly different from his own.

In 1936, Andy Warhol contracted rheumatic fever. Although he seemed to make a full recovery, he developed complications in the form of Sydenham’s chorea. Also known as Saint Vitus’ dance, Sydenham’s chorea is characterized by uncoordinated, jerking movements of the limbs. Already considered a strange child, the condition exacerbated the bullying Warhol suffered at the hands of his classmates. The condition became so severe Warhol was left bedridden for weeks at time. During his convalescence, he busied himself drawing, creating collages out of comic books and poring over movie magazines. Although he didn’t know it at the time, these sickbed activities foreshadowed his future.

Andy Warhol, teen artist

Ondrej Warhola had high hopes for all his sons, but in the months before his death, he had pinned his hopes for changing the family’s working-class legacy on young Andy. As recounted in The Life and Death of Andy Warhol by Victor Bockris, Paul, the eldest of the Warhola children, had disappointed his father by dropping out of high school. Middle son John became the head of the family. A disciplined, hard-working man, Ondrej Warhola had managed to save the incredible sum of $15,000, some of which was to be reserved for Andy’s college fund.

The year before his father’s passing, Andy Warhol entered Schenley High School. A racially diverse, middle-class high school, Schenley’s record for academics was mediocre, but it did have an outstanding art program. Determined to fulfill his father’s expectations, Andy threw himself into his art. Soon, Warhol surpassed his peers in both ability and discipline. “In Miss McKibbin’s art class, he went straight to his desk and drew and drew,” former classmate Lee Karageorge told Bockris. “But socially, he was sort of left out. He wasn’t even in the art club because his talent was so superior to the rest of us.”

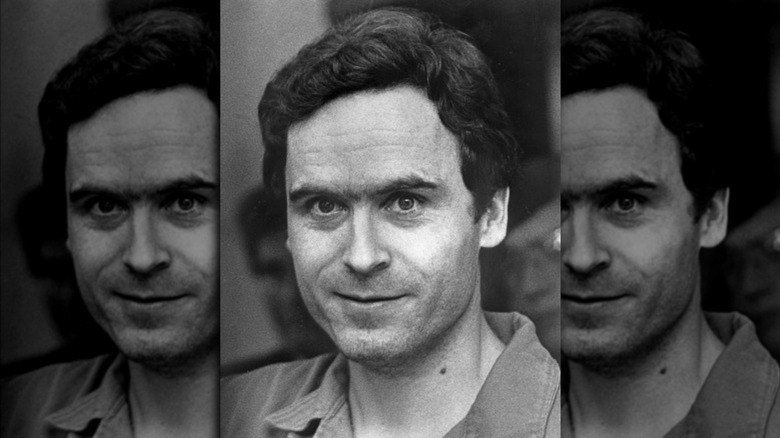

In his senior year, Warhol won the prestigious Scholastic Art and Writing Award, putting him in the company of such luminaries of art and literature as Truman Capote and Hughie Lee-Smith. Accepted to both the University of Pittsburgh and the Carnegie Institute of Technology, Warhol chose the latter for its superior art program.

Andy Warhol developed his distinctive approach working as a commercial artist

Although his fellow students at Carnegie recognized the quiet, unusual young artist as an exceptional talent and innovator, the faculty was divided on whether Warhol had the skills to complete his studies. At the end of the term, Warhol was dropped from the school. Warhol spent the summer selling vegetables with his brother. He drew the people he saw, filling a sketchbook with scenes of everyday life. Those drawings would get Warhol reinstated at Carnegie the following autumn.

Many of Carnegie’s instructors came from industrial and commercial art backgrounds. Introducing Warhol to the Bauhaus school, a German art movement based in fusing art and technology, Warhol’s professors set the artist on the path that dominated his future work. Bauhaus’ emphasis on art as business would directly influence Warhol’s development of his Factory studio.

In 1949, Warhol graduated from the Carnegie Institute of Technology and traveled to New York to find work. As detailed in Warhol, Tina Fredericks, art editor of the fashion magazine Glamour, bought one of Warhol’s drawings and commissioned him to create a series of shoe drawings. When the work was published, the final “a” was omitted from his name. From that day on, Andy Warhola would be Andy Warhol.

in just four years, Warhol rose from obscurity to become the most sought-after fashion illustrator in New York thanks to his bold yet whimsical style. During this time, he developed the techniques of ink blotting and reproduction that would prefigure his use of silk screening in the 1960s.

Andy Warhol becomes a pop art innovator

In the first few years of the 1960s, Andy Warhol turned to painting as his primary artistic outlet. Working as a commercial artist had given him a finely tuned sense of color and balance, which he used to replicate household products, bits of advertising and comic strips, and corporate logos into wholly new works of fine art. Divorced from its commercial and utilitarian context, Warhol’s subject matter took on new meaning. Although the art establishment in New York didn’t immediately get this aesthetic, Andy Warhol would soon revolutionize the art world as pop art’s leading exponent.

According to Andy Warhol by Carter Ratcliff, the artist initially struggled to land a one-man exhibition in New York despite his status in the world of commercial art. In 1962, the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles displayed a series of his Campbell’s Soup Can paintings. The West Coast reaction was overwhelmingly negative. Another art dealer cheekily put a stack of actual soup cans on display with a sign reading, “Get the real thing for 29 cents.”

With the help of art patron and documentary filmmaker Emile de Antonio, Warhol at last secured a showing at New York’s Stable Gallery. Featuring brightly rendered silk-screened images of Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe, Warhol’s Stable exhibition was a revelation. Art critics hailed Warhol’s work as a comment on the exploitative nature of popular culture, and the response was immediate. Overnight, Andy Warhol became the toast of the Manhattan art scene.

Andy Warhol's Factory

As detailed in Pop by Tony Sherman, in 1963, Andy Warhol moved his base of operations from an abandoned firehouse to the fifth floor of 231 East 47th Street in Midtown Manhattan. The cavernous former hat factory would be transformed into Warhol’s wonderland — a citadel for the manufacture of art and a magnet for outsiders, celebrities, drug addicts, and drag queens.

Having marveled at the “silverized” apartment of his friend, hairdresser and self-proclaimed magician Billy Linich, Warhol employed him to give his new studio the same treatment. Covering every surface in silver paint and aluminum foil, Linich transformed the space into a shining art palace that evoked both the space-age future and Hollywood nostalgia. “It was the perfect time for silver,” Warhol wrote. “Silver was the future. It was spacey […] And sliver was also the past — the Silver Screen […] And maybe more than anything else, silver was narcissism — mirrors were backed with silver.”

Warhol’s new studio, the Factory, lived up to its name. With help of hired assistance and hangers-on, the artist produced his silk-screened paintings on a virtual assembly line not unlike the mass-produced products many of them depicted — an irony not lost on Warhol.

The original Factory lasted until 1967, when the building was sold to make way for an apartment complex. Those four years were among the most productive of Warhol’s career, during which the artist would experiment with sculpture and film, expanding pop art from an artistic movement to a personal philosophy and lifestyle.

Andy Warhol was a brilliant experimental filmmaker

A lifelong fan of classic Hollywood movies and movie stars, Andy Warhol’s entry into cinema was a natural extension of his artistic philosophy. Warhol summed up his thoughts on the importance of film on contemporary life in his 1985 book America: “It’s the movies that have really been running things in America ever since they were invented. They show you what to do, how to do it, when to do it, how to feel about it, and how to look.” Throughout the mid-1960s, the artist attempted to recast the most American art form in his own image.

Just as he had taken advertising and pop culture iconography and redefined it by separating it from context in his paintings, Warhol divorced film from the restrictions of narrative, bringing the medium back to its experimental, silent roots. As exemplified by his 1963 film Kiss, a 50-minute montage of couples kissing, Warhol’s cinematic style focused on image and repetition free from plot. Like a piece of instrumental music, Warhol treated the moving image as abstraction, leaving interpretation to the audience. Sleep, completed in 1964, expanded on Warhol’s ethos of simplicity. A five-hour loop depicting his partner John Giorno sleeping, the film alternately impressed and frustrated critics.

As for assigning meaning to his films, Warhol was characteristically ambivalent. “All my films are artificial, but then everything is sort of artificial” Warhol said. “I don’t know where the artificial stops and the real begins.”

Andy Warhol's stable of superstars

Aside from his Campbell’s Soup Can paintings, Warhol is probably best known to people with a passing familiarity with the artist for his famous quote: “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” Although those words have become synonymous with short-lived fame and tabloid stardom born of scandal and the public’s appetite for sensationalism, they have been prophetic in the age of the internet, when the potentiality of celebrity is open to virtually anyone.

According to Victor Bockris, the idea of fame and the machinery of celebrity creation were a guiding obsession for Andy Warhol. Just as images of product packaging and pop culture icons were grist for the pop art mill, so was life as lived by the famous. From artists and musicians to junkies, drag queens, and Bohemians, Warhol declared the denizens of his famous Factory “superstars.” A microcosm of the studio system of the 1930s and ’40s, Warhol’s circle of associates and muses generated publicity for the artist while enjoying a degree of fame by association. Among them were actress and model Edie Sedgwick (the most celebrated of Warhol’s superstars), musician Nico, and artist and author Ultra Violet.

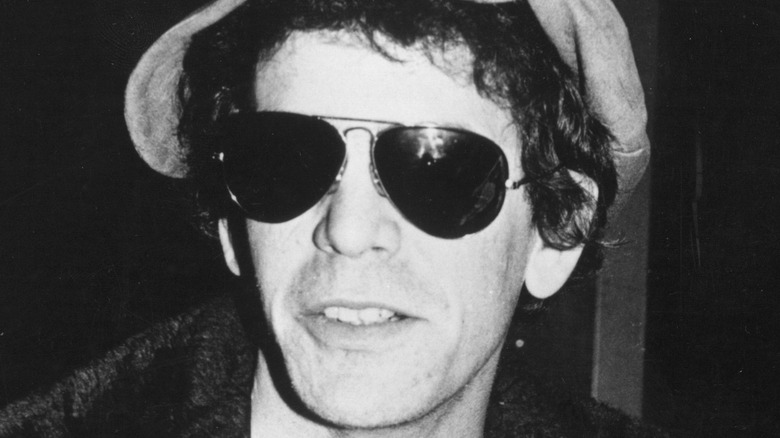

In 1972, musician Lou Reed released the single “Walk on the Wild Side” from his second solo album Transformer. The song recounts the true stories of several of Warhol’s superstars, including trandgender actresses Holly Woodlawn and Candy Darling and gay icons Joe “Sugar Plum Fairy” Campbell and Joseph “Little Joe” Dallesandro.

Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground

Although the Velvet Underground never enjoyed the fame and record sales of the Beatles or the Rolling Stones, they were nonetheless one of the most important and influential bands of the 1960s. With stark lyrics that tackled such topics as drugs and sex work and a sound that ran the gamut from ambient drones to pure pop, the Velvet Underground prefigured punk and alternative music.

Fronted by singer and songwriter Lou Reed, the eclectic group perfectly captured the attitude of New York’s avant-garde. As recounted in Beyond the Velvet Underground by Dave Thompson, the band caught the attention of Andy Warhol in 1965 at a show at Greenwich Village’s Café Bizarre. Impressed, the artist invited the Velvet Underground to an exhibition of his films. Hoping to further expand his influence on the arts, Warhol offered to manage the band. “The pop idea, after all, was that anybody could do anything,” Warhol explained. “We all wanted to branch out into every creative thing we could. That’s why […] we were all for getting into the music scene, too.”

The band’s debut album The Velvet Underground & Nico, featuring the now-iconic “peel slowly and see” banana album cover by Warhol, was all but ignored by critics. Selling only 30,000 copies in its first five years of release, the album eventually became an underground hit. In a testament to the band’s influence, musician Brian Eno would reflect, “Everyone who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band.”

Andy Warhol was nearly assassinated

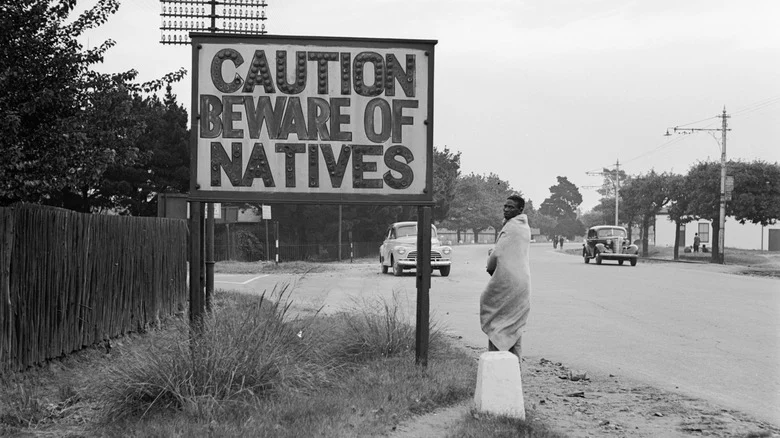

The Factory was a magnet for Bohemians, artists, celebrities, junkies, and eccentrics of every stripe. Among the notorious characters to cross its famous threshold was Valerie Solanas. A radical feminist and would-be Warhol superstar, Solanas had made a reputation for herself as the author of The SCUM Manifesto, a self-published screed arguing for the elimination of men as a solution to the world’s problems.

As recounted by biographer Victor Bockris, Solanas approached Warhol in 1967 about producing a play she had written. Warhol agreed to look over Solanas’ work, but busy and inundated by unsolicited manuscripts and art from would-be artists and writers, he lost the script. By way of apology, Warhol offered an incensed Solanas a role in his film I, a Man. Solanas accepted. For a while, the situation seemed resolved to her satisfaction, but soon, she was again leveling outlandish accusations and threats at the artist.

On June 3, 1968, over the protests of Warhol associate Paul Morrisey, Solanas made her way into the Factory, drew a pistol, and shot Warhol and art critic Mario Amaya. Wounded in both lungs, the spleen, and the esophagus, Warhol survived but faced a lifetime of physical and emotional distress. Diagnosed with schizophrenia, Solanas was charged with reckless assault and sentenced to three years in prison.

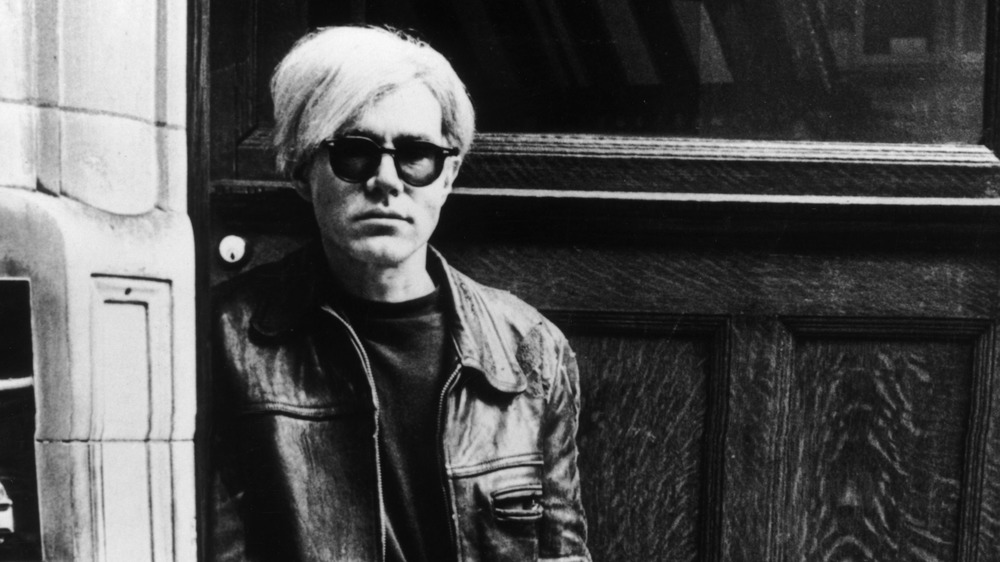

Andy Warhol became a 1970s socialite

At the dawn of the 1970s, Andy Warhol was widely regarded as the art world’s superstar, perhaps the first since Picasso and Dali, according to Victor Bockris. A 1970 retrospective of Warhol’s art reignited interest in Warhol’s paintings, and the prices of Warhol originals skyrocketed overnight. Although he had retired from painting in 1966, Warhol was ripe for a comeback to the medium that made him.

In the new decade, Warhol’s art was becoming big business, and nobody understood that better than Warhol himself. To that end, he created Andy Warhol Enterprises, Inc., a publicly traded corporation whose business was the creation of art. To keep the IRS at bay, all contracts and commissions for paintings were credited to the company.

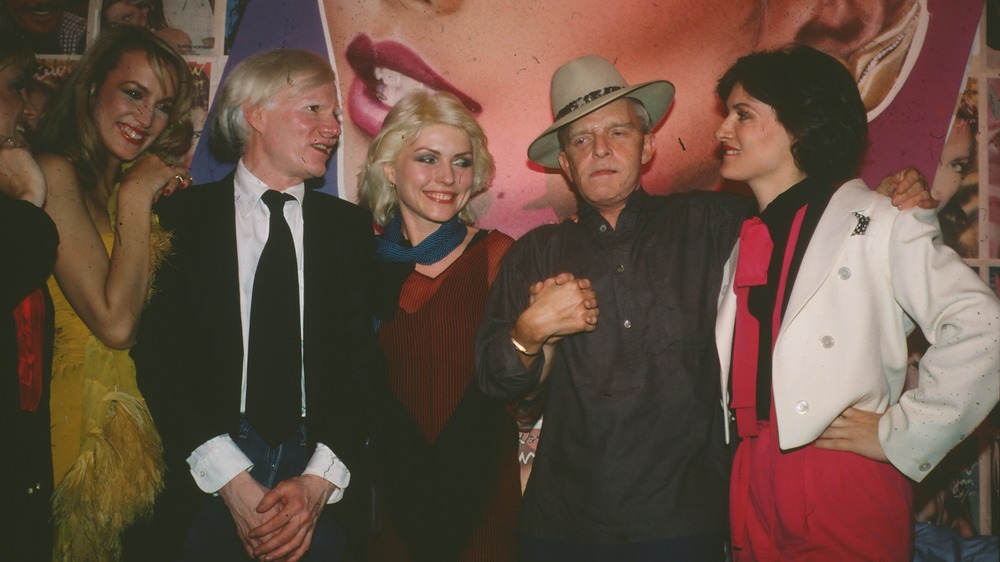

In contrast to his reputation as a 1960s eccentric, Warhol became more of a businessman in the ’70s. Accepting commissions from heads of state and celebrities, Warhol was no longer an underground figure but a full-fledged New York socialite who could be regularly found at Studio 54 in the company of such celebrities as Liza Minelli and Truman Capote.

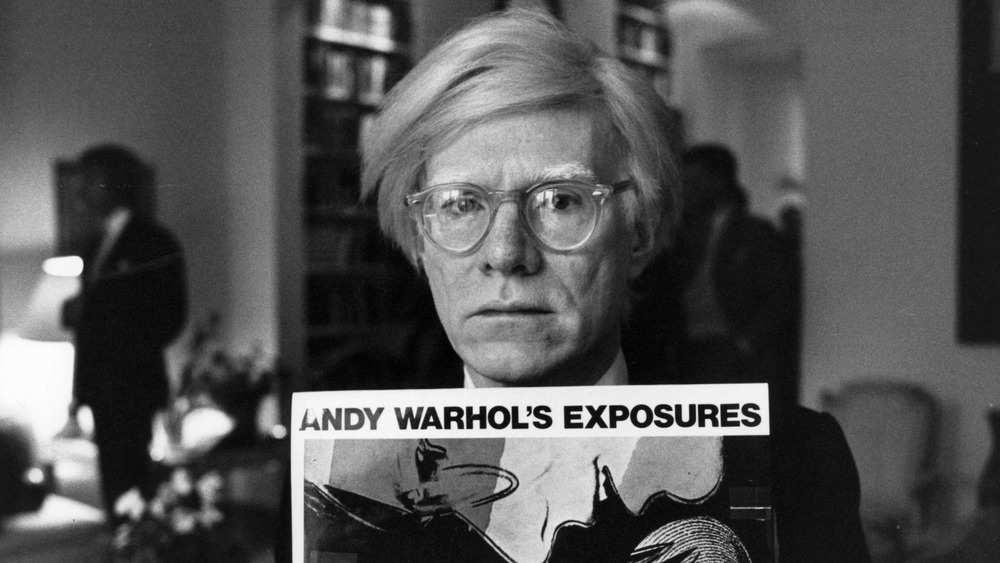

Andy Warhol in the 1980s

As recounted by Victor Bockris, the early 1980s saw Andy Warhol facing a backlash in the artistic community for what they perceived as crass commercialism in his art. In a decade marked by conspicuous consumption, the accusations leveled at Warhol seem ironic in retrospect. Under fire for his celebrity portraits, Warhol faced some of the harshest criticism of his career. Warhol, who had never shied from the commercial element that had always been central to his pop art philosophy, took the criticism in stride. When asked by a television reporter to respond to a critic’s declaration that the paintings were terrible, a gum-chewing Warhol nonchalantly replied, “He’s right.”

Nevertheless, a new generation was venerating Warhol. Among them was a hip and iconoclastic street artist named Jean-Michel Basquiat. A proponent of Neo-expressionism, Basquiat partnered with Warhol on joint art exhibitions, the young artist renewing Warhol’s passion for painting.

A routine medical procedure led to Andy Warhol's death

In 1973, Andy Warhol began suffering from painful gallstones, according to Victor Bockris. Despite frequent flare-ups, Warhol’s fear of hospitals prevented him from seeking treatment. By the end of 1986, his condition had become life-threatening, and by February 1987, tests revealed that Warhol’s gallbladder was severely infected. If it wasn’t removed, it would become gangrenous, his doctor warned.

After five hours of surgery, Warhol was recovering and in good spirits. Before dozing off, he watched TV and chatted with his private nurse. Despite his excellent prognosis, Warhol experienced a sudden heartbeat irregularity that led to his death at age 58 on February 22, 1987. Citing inadequate care, Warhol’s family sued New York Hospital for malpractice. They settled out of court for $8 million.

Interred in his signature silver wig and sunglasses, Warhol was buried next to his parents in Pittsburgh. Since 2013, Andy Warhol’s grave has been the subject of a continuous streaming video feed.

The Real Reason Lou Reed Quit The Velvet Underground

Bizarre Fan Theories About Celebrity Deaths

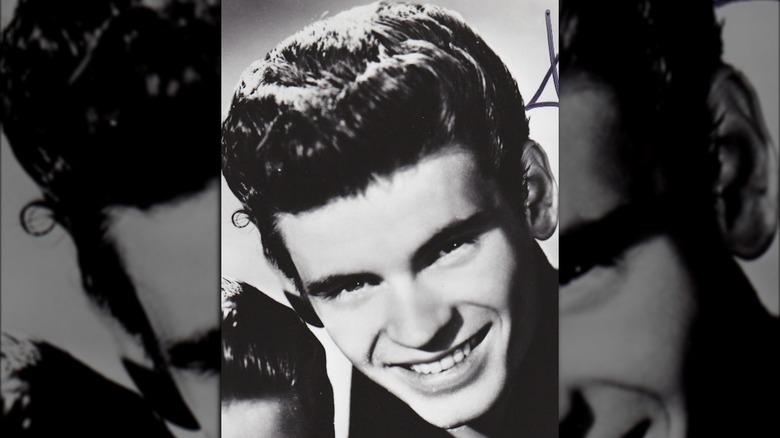

What Was Don Everly's Net Worth When He Died?

Inside The Time Hells Angels Sued Marvel

What's Come Out About Eddie Van Halen Since His Death

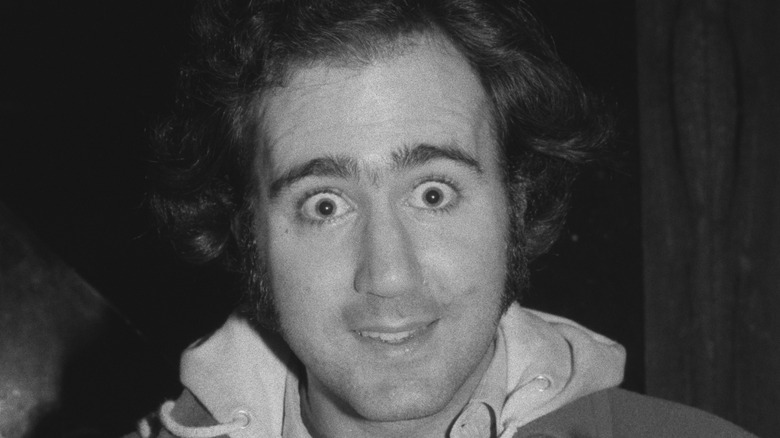

The Truth About Andy Kaufman's Imaginary Feud With Jerry Lawler

The Untold Truth Of Otis Redding

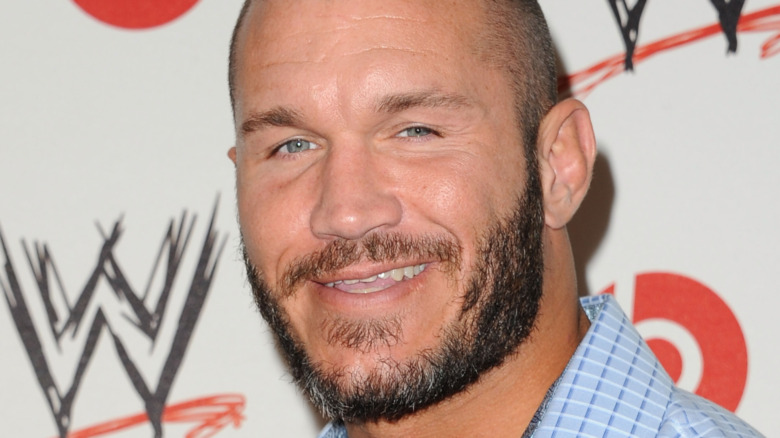

How Much Is Randy Orton Worth?

What The Last Year Of Patrick Swayze's Life Was Really Like

The Tragic Story Of Prince's Last Dove