The Crazy Story Of Edmund Hillary’s Hunt For The Yeti

If you stumbled across an abominable snowman, would you recognize it? Although you might imagine an NBA athlete-sized creature covered in a shaggy albino coat, Live Science paints a decidedly different picture. According to a compilation of reports of the mythic yeti, ruddy brown or dark gray hair covers it from head to toe. It weighs between 200 and 400 pounds and stands, on average, six feet tall. In other words, yetis lack the tremendous stature of Washington’s Bigfoot or Florida’s skunk apes. Of course, like so many folkloric creatures, yetis ultimately come in various shapes and sizes, some up to 8 feet tall if you believe the reports (via the Evening Standard).

Where did the yeti legend originate? Among the people of the Himalayas, oral traditions have preserved the creature as a “figure of danger.” As early as the fourth century B.C., visitors to the region proved intrigued by these creatures. According to National Geographic, Alexander the Great demanded to see a snowman in 326 B.C. during his conquest of the Indus Valley, but locals claimed they couldn’t show him one. Why not? The beasts couldn’t survive in low-altitude environments. Of course, Alexander was just the first in a long line of individuals who would seek out yetis. Among the most famous abominable snowman expeditions? That of famed explorer Sir Edmund Hillary.

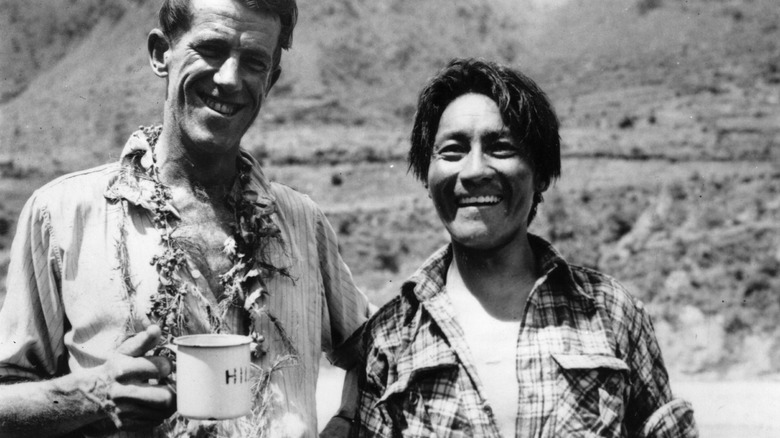

New Zealand's famed mountaineer

New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary was born in Auckland on July 20, 1919, per Britannica. He became the first man to conquer the world’s highest mountain, Mount Everest, on May 29, 1953, along with Sherpa Tenzing Norgay (via History). When not scaling mountains for the British Commonwealth, Hillary worked as a beekeeper.

Hillary and Norgay were part of a much larger expedition led by Colonel John Hunt, which included some of the best climbers and Sherpas at the time. Hillary had already completed four Himalayan treks in two years and was “at the peak of fitness” in 1952, according to National Geographic.

The final ascent would be left to Hillary and Norgay, who reached the top of the world after traversing a perilous 40-foot-high rocky outcropping. According to Ripcord Travel, Hillary and Norgay claimed to have seen large footprints during their ascent. They declared the prints potential physical evidence of what locals referred to as “metch kangmi,” or the “filthy snowman.” Mistranslated by the media, the name “abominable snowman” stuck, according to Atlas Obscura.

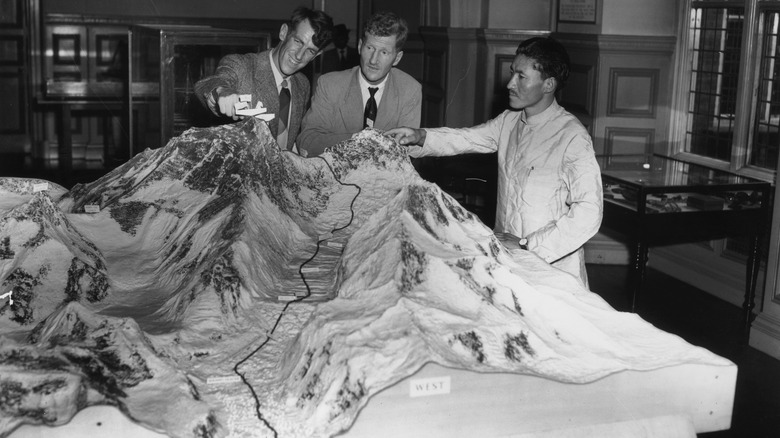

Hillary considers how to summit Everest without oxygen

Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay relied on “open-circuit” breathing systems to successfully support their climb of Everest, per The Engineer. The device weighed around 40 pounds and provided 2,400 liters of oxygen to the climbers. Users decided how much oxygen to breathe every 60 seconds, significantly impacting how long supplies lasted. While carrying the heavy contraption proved a cumbersome necessity, Hillary hoped to devise a means of conquering Mount Everest without oxygen.

According to Michael Gill, author of “Edmund Hillary: A Biography,” as early as 1958, Hillary consulted with physiologist Griffith Pugh for help. Corresponding via letters, they developed a plan of action for summiting Everest without oxygen, involving acclimatizing at 20,000 feet for half a year before attempting the climb. But they needed some serious funding to make this happen.

In a letter to Pugh, Hillary wrote: “I find it difficult to raise too much enthusiasm for the attack by the old route until something more tangible is available on the financial side … I’m damn certain we’d need a lot of cash.” To secure this funding, Pugh and Hillary needed a way to capture the popular imagination. Only one sure way to do this existed — incorporating a hunt for the yeti into their expedition.

Explorer of the year proposes a yeti search

In 1959, Sir Edmund Hillary received the “Explorer of the Year” award from the men’s adventure magazine, Argosy, according to “Edmund Hillary: A Biography.” During the awards banquet in New York, Hillary connected with John Dienhart of World Books in America, and he realized Dienhart and World Books could provide the funding necessary for their expensive attempt to summit Everest without oxygen.

How did Hillary gain Dienhart’s attention and funding? By proposing a “thorough search for the Abominable Snowman or Yeti” (via “Edmund Hillary: A Biography“). The move proved strategically brilliant. After all, the 1920s had seen multiple attempts to scale Mount Everest, and these attempts had ignited the public’s excitement about the abominable snowman.

Dienhart took the bait, and Hillary and Griffith Pugh couldn’t believe their luck. They suddenly found themselves in possession of $125,000, the exact figure needed to fund their trip. Michael Gill quotes Hillary writing of Dienhart’s funding requirements: “[They] gave me practically a free hand.”

The search sparked by footprints

Sir Edmund Hillary drew on excitement related to four photos taken in 1951 by Eric Earle Shipton, a British mountaineer, per NBC. Shipton’s photos launched yeti fever anew, providing the ideal context for Hillary and Griffith Pugh’s later expedition. Of the four images, one provided scale with an ice ax and another with a hiker’s boot.

How did Shipton come across the footprints, and were they legit? According to Live Science, Shipton was leading an expedition when he and his crew stumbled across the strange imprints in the snow. Shipton declared them a physical sign of the presence of yetis, and locals agreed with this assessment.

One of Shipton’s infamous pictures contains a note written by Tom Bourdillon, an expedition team member. Bourdillon details the location of the prints at an elevation of 19,500 feet, declaring they belonged to “no animal known to live in the Himalaya.” Another expedition member, Dr. Michael Ward, later reported the footprints’ elevation at between 16,000 and 17,000 feet in his case report “Everest 1951: The Footprints Attributed to the Yeti — Myth and Reality,” per Science Direct. What did Ward think created the tracks? He posited several theories, including humans with deformed toes, bears, and even monkeys.

The Himalayan Scientific and Mountaineering Expedition

With funding secured and public excitement stoked, the Himalayan Scientific and Mountaineering Expedition, also known as the Silver Hut expedition, embarked on their adventure, per Frontiers in Physiology. The expedition stretched from September 1960 through June 1961. Members of the expedition assembled in the so-called “yeti stronghold” of the Rolwaling Valley near Kathmandu. A remote location, it runs along the frontier between Nepal and Tibet (via One World Trekking), and it’s got all the vibes you’d expect from a supposed abominable snowman hangout: isolation, snow, and rugged, ice-clad mountains.

The Sherpa refer to the Rolwaling Valley as “the grave,” which had to give expedition members a warm, fuzzy feeling. To this day, the Rolwaling Valley trek remains one of the most challenging mountaineering experiences in Nepal, as reported by Mountain IQ. Why did the Silver Hut expedition settle on this location? Because it’s where Eric Shipton captured his yeti footprints in 1951.

What else did the Silver Hut expedition know about the footprints? In his case report (via Science Direct), Dr. Michael Ward described two sets of tracks, one indistinct and the other more precise, which Shipton’s expedition followed down a glacier. In the aftermath of the find, Ward noted, “There have been innumerable descriptions of unusual footprints found in the snows of the Himalaya and elsewhere; and bear tracks and bears have been seen, sometimes attacking Tibetan shepherds and yaks.” Had the tracks been made by bears? The expedition dug in to find answers.

The three-part yeti expedition launches

The Silver Hut expedition included a three-pronged investigation requiring a crew of 310 sherpas, 21 scientists, and various specialists and climbers (via TMC Net News). The substantial team had multiple tasks to complete besides searching for the yeti. Expedition goals included establishing two high-altitude huts above Tengboche and studying the effects of high altitude on human beings.

Soon, members of the party discovered a set of footprints on the Ripimu Glacier, which inspired them to prepare for the abominable snowman. To do this, the expedition set up various yeti “traps.” According to John B. West’s book “High Life: A History of High-Altitude Physiology and Medicine,” these included tripwires, tranquilizer-loaded capchur guns, telescopes, and cameras at 18,000 feet. The crew also hid microphones throughout the region, hoping to capture the telltale high-pitched whistle of the yeti. These so-called whistles comprised a common feature of local myths, often preceeding an attack (via The Press). But the best technology the early 1960s had to offer failed to capture any compelling new evidence.

Besides outfitting the Rolwaling Valley with the latest technology, Hillary dove into an examination of alleged physical materials. The expedition purchased every supposed snowman artifact they could get their hands on. According to Michael Gill’s “Edmund Hillary: A Biography,” the team soon found themselves in possession of “a goat skin, a dried human hand, two small red pandas, a fox — and a yeti scalp.”

The Wild Kingdom's Marlin Perkins provides a skeptic's perspective

Marlin Perkins, director of Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo and eventual host of Mutual of Omaha’s “Wild Kingdom,” supported Sir Edmund Hillary’s quest for the yeti. He also hoped to capture one based on the 1951 photos circulating of the alleged snowman’s footprints.

Perkins even joined the men in the Himalayas during their Silver Hut expedition, and he proved a much-needed asset. Why? Perkins shed invaluable light on the treasure trove of yeti evidence compiled by Sherpas over the centuries. While Perkins hoped to discover a long-lost species in the wilds of the Himalayas, everything he saw had a natural (and well-documented) explanation. He would later report on his findings in a 1963 episode of “Wild Kingdom.”

This biological material reportedly included two alleged yeti scalps located in the villages of Pangboche and Khumjung and a collection of other items. What did the team discover with the help of Perkins’ careful eye for animal artifacts? According to Joshua Blu Buhs in his book “Bigfoot: The Life and Times of a Legend,” two Tibetan blue bear pelts, a “human tail,” “lightning excreta,” the petrified penis of a lama (a Buddhist monk), and a “horse’s horn.” Sounds more like the makings of a kitschy roadside attraction than the underpinnings of a world-famous scientific expedition, right? The abominable snowman legend was disintegrating, one artifact at a time, before their eyes.

Marlin Perkins explains the unexplainable

In 1963, Marlin Perkins would address the abominable snowman theory on one of the first episodes of “Wild Kingdom.” Perkins described the yeti as an animal with reddish-black or brownish hair and a ferocious appetite for yaks and people. He took the tack of a zoologist, comparing the footprints photographed by Eric Shipton to those of chimpanzees and gorillas at his zoo. In the process, he demonstrated their utter lack of congruence, debunking the notion of the yeti as a primate.

Perkins also delved into a fascinating anecdote about footprints in the Himalayas. Roughly three miles from where Shipton and his team took their famed photographs of the tracks, the Silver Hut expedition ran across a fresh set. The group’s Sherpas declared them among “the best yeti tracks they’d ever seen.” The expedition followed the prints for more than a mile, studying them intently.

No other animal had disturbed the snow on the glacier that day. As for the tracks, some remained shaded, while others received direct sunlight for hours. By comparing the tracks, they came to a startling conclusion: A fox had made all of the prints found that day. How had some of the tracks taken on the look and form of much larger yeti footprints? Due to the combined effects of sunlight and melting, which rendered the prints impressively large and intimidating.

The yeti scalp goes on tour

All avenues of evidence appeared to be drying up when it came to the yeti. Nevertheless, Sir Edmund Hillary remained intrigued by the yeti scalp at a Sherpa temple called Khumjung Gompa. Per Stars and Stripes, Hillary explained, “The scalp has unusual features. It is shaped like a Tibetan priest’s cap — rather like a crown — and it has a ridge of hair on top of it. The scalp is hard to explain. It’s a convincing sort of specimen.”

According to Marlin Perkins, the scalp “looked like a hairy, pointed, brimless helmet.” Hillary wanted to take the scalp to Europe and the United States for further examination, according to TMC Net News. After speaking with locals, Hillary secured the scalp by offering to build a Sherpa school in Khumjung and pay its first instructor. This agreement would spawn some of Hillary’s most important work in raising funds for the people of the Himalayas.

The scalp and other relics (including skins and skeletal hands) traveled to Europe and the U.S. accompanied by a village elder named Khunjo Chumbi. As Hillary noted, the scalp was “the sort of thing that must be examined by people better qualified than us” (via Stars and Stripes).

The experts weigh in on the snowman's scalp

How had the Sherpas come to own the yeti scalp in the first place? According to their oral tradition, the revered scalp represented the only remaining testament to “a great gathering of the yetis 240 years ago by a mountain village” (via Stars and Stripes). As related by the Sherpas, villagers got the yetis drunk so that they’d fight among themselves (and presumably prove easier targets for their human counterparts). Yet, all escaped unharmed except for a single pregnant female. Killed by a Buddhist monk, only the female yeti’s scalp remained.

From New York to Chicago, Paris to London, various scientists and researchers examined the scalp and other artifacts. Their conclusion? Each artifact had a natural explanation. The hides were those of Tibetan blue bears, the skeletal hands had human origins, and as for the scalp? Humans had crafted the artifact using a serow antelope’s hide (via “Wild Kingdom“).

How did Chumbi respond when questioned about these inconsistencies? According to TMC Net News, he stated, “In Nepal, we have neither giraffes nor kangaroos so we know nothing about them. In France, there are no yetis, so I sympathize with your ignorance.” Chumbi even promised to find a living, breathing, abominable snowman on a second expedition. But Hillary felt unconvinced. He stated, “I have never believed in the existence of the snowman. The yeti is not a strange, superhuman creature as has been imagined. We have found rational explanations for most yeti phenomena,” per Stars and Stripes.

Aftermath of the yeti expedition

Despite whispered rumors of faked footprints and the lackluster results of Sir Edmund Hillary’s expedition, the adventure did achieve one of its primary goals. It earned its sponsors back their initial investment of $125,000 and then some (via TMC Net News). The Silver Hut expedition also brought in enough revenue to bolster Sherpa aid programs for the next ten years. And Hillary would go well beyond his original word, generating funds for medical facilities, schools, and other projects in the Himalayas for the rest of his life, per the Los Angeles Times.

But Hillary and Marlin Perkins’ rational explanations of the yeti wouldn’t deter future investigators from taking up a hunt for the abominable snowman. Moreover, not all of the evidence gathered by Hillary proved as easy to explain away as the scalp and the hides. In 2008, news broke of alleged yeti sightings in a jungle on the border between India and Bangladesh.

Strands of hair recovered from the jungle don’t match the most common fauna found in that region. But they did bear a “startling resemblance” to hair strands collected by the Silver Hut expedition, as reported by the Evening Standard. Weighing in on the find, a primate expert named Ian Redmond noted, “The hairs are the most positive evidence yet that a yeti might possibly exist. It might be that the region this animal is inhabiting is remote enough for it to remain undiscovered so far. We are very excited.”

Bear hair or something else?

In 1951, Eric Shipton’s photographs sparked yeti fever, something Sir Edmund Hillary’s Silver Hut expedition in 1960 and 1961 couldn’t totally debunk. In 2013, Bryan Sykes, a genetics professor at Oxford University, proposed a new theory (via CBC News). He claimed that the creature in question is the descendant of a type of ancient bear that last roamed the Norwegian Arctic many millennia ago.

How did he reach this conclusion? By comparing the DNA of two hair samples from the Himalayas with genetic material recovered from a 40,000-year-old polar bear jawbone recovered in Norway. One hair sample came from a “yeti” mummy located in the Western Himalayas and was collected by a French mountaineer in the early 1970s. The other, a single hair, was found more than 800 miles away in Bhutan during the 2000s. Based on the locations of the hair samples, Sykes concluded the species must still live. After all, he noted, “I can’t imagine we managed to get samples from the only two ‘snow bears’ in the Himalayas.”

A 2017 study of DNA from nine alleged yeti hair samples points to a more straightforward conclusion. According to Science, eight of the samples came from known bears found in the area, and the ninth was from a dog. Other recent studies have also shown that most yeti hair samples are from horses, dogs, bears, and even humans. Nevertheless, too many scientists and explorers remain intrigued by this mysterious cryptid to let the hunt die.

The Creepy Reason People Remain Conscious After Being Decapitated

Inside The Mysterious Disappearance Of Rebecca Coriam

The Weird Reason Geese Fly Upside Down

The Mystery Of Belize's Beautiful Great Blue Hole

The Most Dangerous Rivers On The Planet

The Messed Up History Of Dead Whales And Arthritis

Rules Former Presidents Have To Follow

'Super Bowl Of Snake Hunting' Removes 80 Pythons From Everglades

Regular People Who Became Famous For All The Wrong Reasons

Crazy Ways People Are Prepping For The End Times