The Messed Up True Story Behind Party Monster

In 2003, the movie Party Monster took a no-holds-barred look at New York City’s club culture and its seedy, drug-fueled underbelly. The movie tells the story of a disenfranchised small-town kid called Michael Alig (Macaulay Culkin), who relocates to the Big Apple to look for better things. Alig meets James St. James (Seth Green), who introduces him to the city’s coolest party scene. Michael loves what he sees and becomes the most popular “club kid” in town — that is, until drugs take hold and things start to go downhill fast. Ultimately, Michael’s total and absolute fall from grace is cemented when he becomes involved in the brutal murder of his acquaintance, Andre “Angel” Melendez (Wilson Cruz).

The events of the film may seem outlandish and exaggerated, but they’re actually based on a true story. Michael Alig was a very real person, as are many of the other scenesters depicted in the movie — up to and including Angel Melendez, who really was killed by Alig and his acquaintance. In fact, the real story might just be even more outlandish than the movie version. Let’s take a look at the messed up true story behind Party Monster.

The rise of the Club Kids

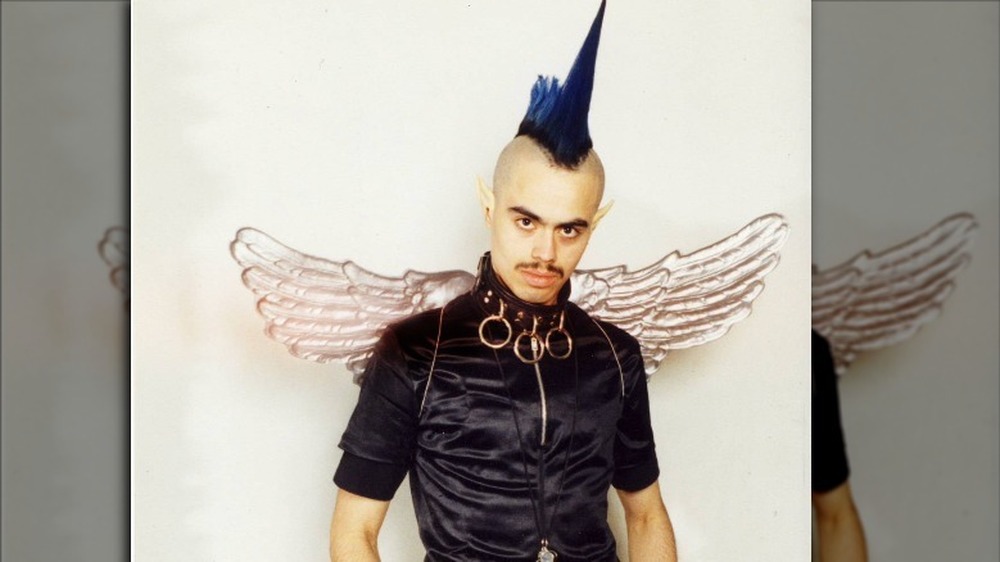

In the 1980s and 1990s, something truly extraordinary was brewing in New York. As Them tells us, this was the era of the Club Kids — a blanket name for a group of young, outrageous, and often LGBTQ creative types who shed away their outcast status and became party scene butterflies. They were highly visible at the parties they attended, and they attended a lot of them. They painted their faces in an outlandish manner, sported unlikely-for-the-time piercings, and wore colorful, commanding costumes.

The Club Kids were out and about, and their open celebration of difference wasn’t just a fringe thing, either. Their ranks included future influencers such as RuPaul, and their scene became a huge deal that inspired artists and designers from Jean Paul Gaultier to Elton John. Per Interview Magazine, the Club Kids were in the habit of creating “glamorous personalities,” and they aimed to make them as inventive and shocking as possible. As such, many of them became locally or even nationally famous, and they made sure that they were as visible as possible by, for instance, holding “Outlaw Parties” at strange and surprising locations.

According to Indie, the scene had its good sides, as it fought to reclaim its members’ humanity and value after the AIDS crisis and during New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani’s crackdown on nightlife. However, its reputation would be forever tarnished by Party Monster and its subject, Club Kid extraordinaire Michael Alig.

The dark underbelly of the Club Kid scene

Per The Guardian, the Club Kid scene started as an attempt to give people who had been outcasts in their own communities a place to belong. As Michael Alig puts it, his intention — apart from self-promotion, of course — was to help “other people who were having a hard time assimilating, like I was when I was growing up. I came to New York and provided an oasis where they could come and be celebrated.”

Then again, the club scene had its dark sides. For one, it was hardly a safe space filled with hugs and pats in the back. Alig himself has noted that because the name of the game was disaffection, the verbal abuse could be rather extreme. “You could say just the worst things about people, nobody was ever offended,” he recalled. There’s also the matter of drugs, which were becoming more and more prominent on the scene. Alig has insisted that the Club Kids weren’t using narcotics to have fun but rather to stave off the horrors of everyday life. “It was more like we need another line of cocaine to never have to face the truth that we were very self-conscious and uncomfortable in our own skins,” he noted.

Michael Alig rules the scene

These days, it may be difficult to understand just how big a deal Michael Alig was back in his heyday. As The Guardian tells us, the 17-year-old Alig moved to New York from Indiana in the early 1980s in order to get a reprieve from his difficult family conditions and the constant bullying because of his homosexuality.

Alig soon established himself as a massive personality in the Manhattan club scene, and he eventually became the main promoter for prominent club owner Peter Gatien. His charisma and the combination of his outlandish getups and scandalous antics made him a popular figure in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as well as a talk show mainstay who was the de facto figurehead of both Gatien’s club empire and the Club Kid scene in general. As such, he was both a legend in his exclusive circles and a mainstream media figure who often prompted reactions from conservative media.

Unfortunately, much like the other clubbers around him, Alig was fueling his outrageousness with copious amounts of drugs. This, combined with peer pressure to constantly outdo himself, caused him to become erratic and sometimes outright nasty. One particularly unsavory story involves an incident in which Alig urinated from a balcony on a female bartender, who was then verbally abused until she cried. Alig has also admitted that he was in the habit of urinating in the drinks.

Andre “Angel” Melendez was a member of Michael Alig's inner circle

According to The Advocate, Andre “Angel” Melendez had his similarities with his acquaintance, Michael Alig. Both were gay men who arrived in New York City around the same time and became heavily involved in the flamboyant Club Kid scene. However, Melendez didn’t have the same intense desire to lead that his friend had. Instead, he was reportedly quite happy to let Alig to rule the Club Kid roost and had plenty of respect for him.

The pair’s power dynamic heavily involved drugs. Melendez was a drug dealer and quite liberal about sharing, as it helped keep him in Alig’s inner circle. It seems that the tactic worked, because according to the Toronto Sun, Melendez was the go-to drug dealer at the Club Kids’ favorite haunts, Limelight and The Tunnel. Meanwhile, Alig became more and more addicted to drugs over time. In fact, The Village Voice reports that he and Melendez eventually came to be at odds over a significant drug debt.

The killing of Angel Melendez

According to The Guardian, there are many versions of the exact circumstances surrounding Andre “Angel” Melendez’s death, thanks to the inaccurate depictions in various pop culture works and exaggerations by both the media and the Club Kids. The crime happened on March 17, 1996, and the perpetrators were Michael Alig and his roommate, Robert “Freeze” Riggs.

Per Variety, the pair killed Melendez with a hammer and later dismembered his body and threw it in the Hudson river in a cardboard box. According to the Toronto Sun, they temporarily stashed the body in a bathtub filled with ice before the dismemberment. As The Village Voice tells it, Riggs brought the hammer down on Melendez’s head, but Alig was the one who killed him by hitting him over and over. The bathtub they used to store the body contained Drano, baking soda, and Calvin Klein Eternity. According to The Advocate, rumor also had it that the killers injected Melendez with Drano. Party Monster shows Melendez physically attacking Alig during an argument, and after Riggs hits Melendez’s head with a hammer a few times, Alig suffocates him and injects him with a syringe.

In Riggs’ original statement to the police, Alig and Melendez had indeed been fighting, at which point he grabbed the hammer and hit the drug dealer. According to Riggs, Alig took the reins after that. First, he throttled Melendez. Then, he filled the victim’s mouth with detergent and closed it with duct tape.

The club scene keeps things quiet

It’s easy to expect that if someone confesses to a murder, the person hearing it will immediately call the police. According to The Advocate, this wasn’t the case with Angel Melendez. The man’s disappearance was noticed, and rumors about the grisly crime started circulating within the Club Kid circles. Some of Michael Alig’s friends even said that he had personally admitted to the crime.

The thing is, while many people were aware of the grim and grisly rumors, Alig was well-known for his attention-seeking ways, and as Variety puts it, he was quite openly bragging about the incident. As such, the whole story seemed like something he might have made up to raise a few more eyebrows.

While the fact that the scene kept silent about a man who freely talked about killing someone might seem unbelievable, it’s worth noting that Alig’s tendency to shock and provoke knew very few bounds. In fact, when he appeared on TV a few weeks after Melendez’s death, he flat-out admitted to the murder in a tasteless way. “He was a copycat, so we killed him,” Alig spoke of Melendez. To be fair, though, in 2014, he insisted, per The Guardian, that his full comment, “You want me to say something shocking like he was a copycat, so we killed him,” had been edited.

The fall of the party monster

While Michael Alig was busy boasting about a crime his club circles didn’t quite believe he had done, the authorities were busy trying to figure out the identity of a dismembered body that had washed up on Staten Island in April 1996, per The Advocate. In October, dental records finally confirmed the deceased’s identity as Andre “Angel” Melendez, and an autopsy revealed several interesting details that seemed to fit with a very particular rumor that was making the rounds in New York City’s club circles. The investigators who went after the suspected killers found, to their surprise, that the club community was very reluctant to help them, choosing instead to protect Michael Alig with their silence. However, Robert Riggs ultimately confessed and revealed Alig’s role in the crime.

According to Deadline, both Alig and Riggs pleaded guilty to manslaughter in 1996. Riggs was paroled in 2010, and Alig was released in 2014 after serving 17 years. In an interview with Rolling Stone upon his release, Alig stated that he still has no explanation for the crime. “Not only is there no reason, there’s no justification,” he said. He also insisted that they didn’t actually intend to kill Melendez.

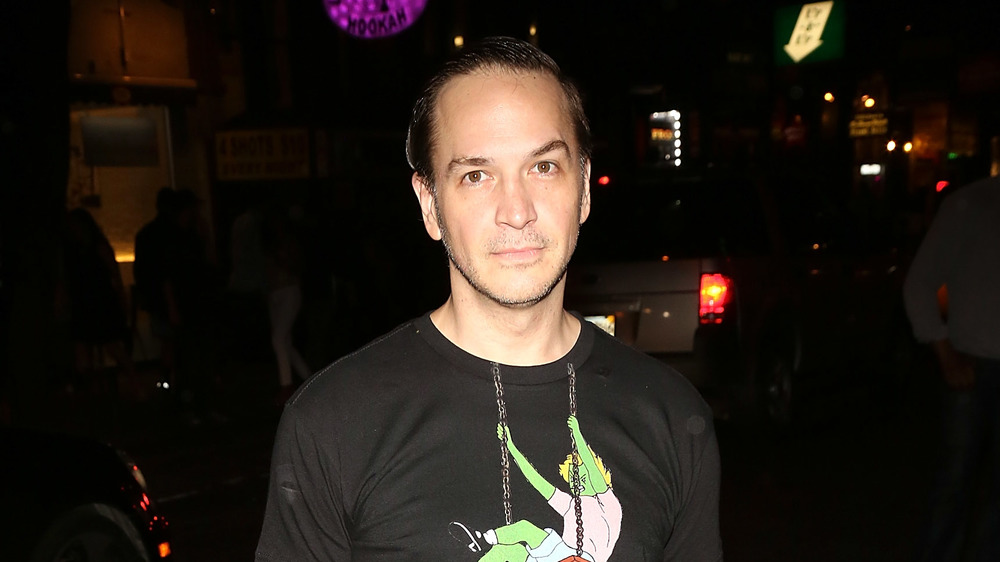

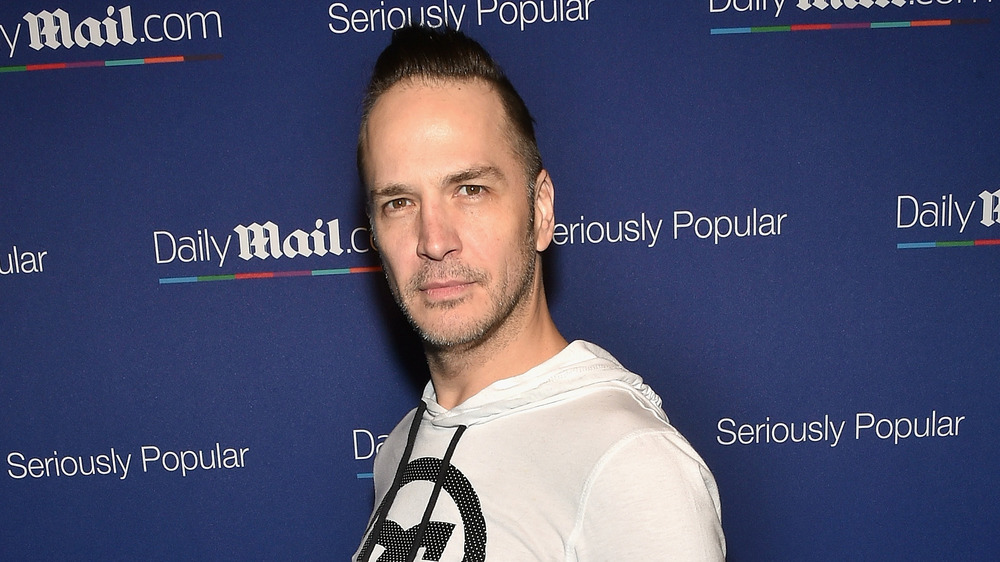

The release and death of Michael Alig

Per Vanity Fair, Michael Alig saw freedom in 2014, after 17 years behind bars. However, as Variety tells us, he was still struggling with the dual prisons of drug addiction and his reputation. His club-era friend James St. James had written the book Disco Bloodbath: A Fabulous but True Tale of Murder in Clubland, which served as the basis for Party Monster, and the dual pieces of fiction had become the “official” version of the events in the minds of the public. Alig has publicly stated that he didn’t much care for the movie’s portrayal of him and pointed out some inaccuracies.

In the end, though, drugs proved to be a much greater enemy. Alig had problems with drug use even after he was released from prison, and he was arrested for using crystal meth in 2017. The final chapter of a story full of tragic twists and turns came on December 25, 2020, when Alig was found lifeless in his apartment in Manhattan. It’s believed that he died of a heroin overdose on December 24.

Party Monster was a critically panned box office bust

The blood- and glitter-filled story of Michael Alig and his cohorts seems like a movie already, so it’s no surprise that it was made into one. Looking at it today, Party Monster managed to get quite a star-studded cast, with a combination of established names and up-and-comers ranging from Home Alone star Macaulay Culkin (who played Alig), Seth Green, and That ’70s Show mainstay Wilmer Walderrama to Chloë Sevigny, Dylan McDermott, and even shock rocker Marilyn Manson.

Unfortunately, it appears that Party Monster either failed to capture the story’s kitsch-filled drama or perhaps embraced it too well. As a look at the film’s Rotten Tomatoes page readily tells us, the critics utterly lambasted Party Monster. “There isn’t an ounce of genuine affection on display,” David Hansen of Newsweek said of the movie while also wondering why the filmmakers insisted on staying on the subject after already making a documentary about Alig. While audience ratings have been rather more generous, people weren’t actually rushing to see the movie. As such, Party Monster’s 2003 single-theater opening weekend raked in a measly $15,163, per Box Office Mojo.

Michael Alig insists that the crime didn't happen like you think

Striking a man with a hammer, suffocating him, and dumping the body in a bathtub with Drano before dismembering and dumping it is an extreme crime at the best of times — but in a 2014 interview with The Guardian, Michael Alig insisted that the way he and Robert Riggs killed Angel Melendez was actually rather more muted than its pop culture depiction.

When one pictures a hammer hitting a head, it tends to be a nasty, bloody affair. Alig said that Riggs actually went about it in a very different way than the classic method depicted in Party Monster. “He hit him with the wooden end of the hammer, not the metal end,” Alig said. “And there wasn’t even a cut on his head when they did the autopsy.” Alig also says that he didn’t smother Angel Melendez and definitely didn’t pour Drano down his throat.

In reality, he argued, the whole thing was a fairly bloodless affair — they simply thought Melendez was unconscious, so they put him on a couch, where he asphyxiated. Later, when they realized he was dead, they put him in a bathtub with baking soda, ice, and Drano to cover the smell. While Alig fully admitted that the pair eventually chopped off the body’s legs before disposing of it, he blamed the dissociation that came with their heroin use and said that he had terrifying PTSD-induced flashbacks about it.

Why Macaulay Culkin took the role of Michael Alig

Some might have found it strange to see Macaulay Culkin, most famous for his early work as Kevin McAllister in the Home Alone movies, playing Michael Alig, a glamor-obsessed clubber-turned-killer. However, in a 2003 interview with ABC News, Culkin himself pointed out that the role of a club hell-raiser isn’t quite as far-fetched for him as one might initially assume. “It’s so easy to see me as this wicked, little thing, you know?” the actor said. “This wicked little like, you know, blond- haired kid, making trouble for everybody.” Culkin also stated that he aimed for more artistic endeavors and tried to avoid doing the kind of movies that had made him famous. “I don’t want to do what I did before,” the actor told Barbara Walters. “Before, it was, you know, it was like people’s livelihoods were on the line … they like built an industry out of me.”

Culkin prepared for the role with a four-hour meeting with Alig in prison, listening to the man and studying his movements and mindset. In the process, he said he noticed that Alig appeared to be quite sorry for his actions but nevertheless seemed to be caught in his old club persona. “He seemed remorseful, but at the same time he was putting up this facade,” Culkin said. “He was putting on the ‘Michael Alig’ act for me, the wild and crazy guy.”

Where Is Roy Orbison Buried?

Why Russell Vitale Can't Stand Post Malone

How Filming 1962's Lolita Destroyed Actress Sue Lyon's Life

Groundbreaking Female Filmmakers Of Early Hollywood

The Real Reason Mick Foley Retired From The WWE

This Is How Much Sheryl Crow Is Really Worth

The Real-Life Person The Oscar Statue Is Modeled After

The One Moment That Ruined Sly Stone's Career

The Untold Truth Of The Indigo Girls

The Untold Truth Of Emmylou Harris