The Messed Up Truth About This Children’s Survival Reality Show

Kid Nation was a CBS reality show that aired only one season in 2007. In the show, 40 kids ranging in age from 8 to 15 were thrown into a deserted town and made to create their own society — without adult supervision. This means that they had to cook their own meals and clean their own toilets, many for the first time, in addition to establishing a community and figuring out how to coexist. With no electricity, the only water coming from pumps on the edge of town, and food options being restricted to canned produce and live animals, the kids had a challenging six weeks ahead of them.

Not only did the premise — which drew a considerable amount of Lord of the Flies references — raise eyebrows, but the production’s sketchy practices drew a variety of legal charges in the show’s aftermath. From bleach-drinking and chicken-butchering to wage theft and neglect, here is the messed up truth of Kid Nation.

The kids had no adult supervision

After being dropped in the middle of the desert, the kids met their host Jonathan Karsh. He would tell them that although they won’t have any adults to help them, they will have a group of four leaders called the town council. These four kids — who were flown in by helicopter in a dramatic flourish — each headed up their own team of children. They were responsible both for running their team and conferring with the rest of the council to keep their camp, an abandoned Bonanza City, N.M., up and running. These children were supposed to act like the closest thing the kids have to adults.

Except there were plenty of adults on set. While the only adult the viewer sees is Karsh, who appears at challenges and weekly town meetings, there were 12 camera crews present to capture all the action. According to contestant Michael, whose 2013 Reddit thread revealed many details about the show, each crew had about four adults, so there were almost always watchful eyes. Additionally, Micheal claims to have “bummed” snacks from the camera crew and even speaks fondly of them, saying, “I loved those guys!” The Los Angeles Times reports there was a medic, child psychologist, and an animal wrangler for all the rattlesnakes that slithered through town. That being said, there were definitely moments where you would think one of the many adults should step in — like when contestant Colton starts provoking a bull on the outskirts of town — but hey, that’s showbiz, baby!

“I think I'm gonna die out here”

Surprisingly, the kids had virtually no idea what they were getting into. In the opening scene of the first episode, the contestants are chatting on a school bus as it careens through the desert. They seem to know that they are going somewhere without adults, but beyond that, they have very little information. Most are excited, some are nervous, and they are all speculating about what is about to happen to them. “I’m not going to be with my parents, there’s no adults, and I think I’m gonna die out here because there’s nothing,” says 8-year-old Jimmy, matter-of-factly. Another 8-year-old, Mallory, expresses that, “it’s kinda hard to believe I’m gonna be living out here,” but she is glad to have her sister along for the ride.

In his Reddit thread, contestant Michael confirmed that the children had no clue what was going on when they got dropped in the New Mexico desert. “Yes, that’s true! And we weren’t allowed to talk at first either. It was very strange and overall kind of sh***y.”

As they exit the bus and gather more details from host Jonathan Karsh, they seem to build off of each other’s excitement. They even cheer as they run towards the 40-days worth of supplies they are made to haul over 2 miles of desert terrain, all piled on to old-timey wagons. Most seem genuinely excited to make something of themselves, even if that feeling fades a bit over the long hike to Bonanza City.

They were forced into a class-based society

After being divided up into four teams, the kids competed in a challenge puzzle each week. The challenge was both physical and mental, as is typical in this style of reality show, and themed to their surroundings. Examples of challenges included routing a water hose through a series of obstacles, or, you know, herding sheep. The purpose of these challenges was to determine their place in society for that week, as well as their paycheck, in the class-based system established by the producers.

The first place team was the upper class, who could work as little or as much as they choose and get paid $1 an hour. Second place was the merchants, who ran the town store and got paid 50 cents. Next were the cooks, who provided meals for the town and were paid 25 cents. In last place were the laborers, who got paid 10 cents to clean the latrines and fetch water. Luckily, the kids didn’t have to pay for meals, but they could use their hard-earned “buffalo nickels” to buy luxury goods like candy and books in the town store.

While classes were rigid for the week, and challenges the only opportunity to advance up the societal ladder, some kids took to bartering or offering services for extra cash. In the first episode, available on YouTube, contestant Sophia dances in the town center in a bid to earn enough money for a bike, which she can’t afford as a laborer. What a lively town!

Hey, kid! TV or outhouse?

The challenge in each episode held even more glory than a few measly buffalo nickels. If every team finished under an allotted time period, the council was given a choice of reward for the whole town. The rewards purposefully tested the kids’ long-term versus short-term gratification, giving them the choice between something fun that kids love or something useful for their burgeoning society.

In the first challenge, it was seven more outhouses or a TV they could watch at any time. A kid-based society and unlimited TV time? That’s any child’s dream! The second challenge was even more heavy-handed, with the option of two more water pumps, or a 45-foot water slide for the middle of town. Come on, people.

In the words of Kid Nation producer Tom Forman, the rewards were lessons to be learned in that they “really got to what matters to kids and let them experience what it means to make decisions between immediate gratification and long-term consequence.” However, as Tammy Iftody points out in her dissertation on childhood and performance, the “kid-like” thing to do as outlined by the producers (like picking the waterslide) represents a major assumption about the behavior of the children and pins them into a narrative they might not necessarily have created based on their own organic actions. In fact, the contestants usually go with the more “mature” option, proving that they mostly know by now how to make this type of decision.

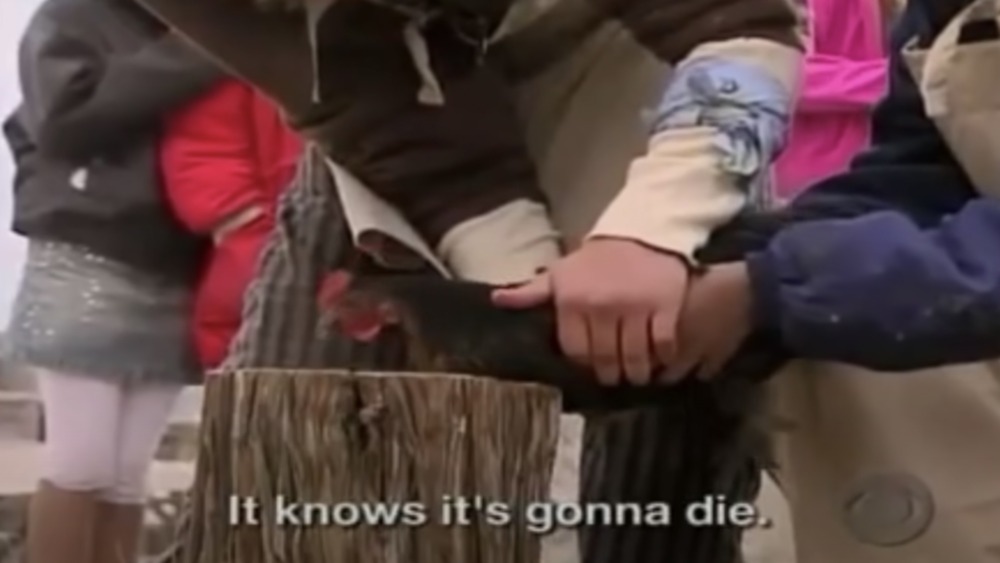

To kill or not to kill

By episode two, the kids were getting tired of the canned food they had been living off of. At this moment the producers revealed that if they wanted meat, they were going to have to get it themselves. They would have to kill a chicken, as seen in these clips via YouTube.

Excited by the prospect of fresh meat but equally disturbed by the idea of ending a chicken’s life to get it, the council put the matter to a public vote. “We are thinking about killing a chicken,” one council member hesitantly announced at the meeting later that day. After much heated debate and some questions about how vegetarians can manage (answer — “they have, like, tofu and stuff”), they decide to kill the chicken.

Emilie, an animal lover who claims to break wild mustangs on her parents farm, is distraught. Not knowing what else to do, she runs to the chicken coop with two other kids, and they barricade themselves inside in protest. Although they are pretty riled up (one of the protestors wonders aloud, “are they, like, gonna hang them like they did Saddam Hussein?”), their fellow Bonanza City residents eventually calm them down enough to have a conversation about the greater good, and they commence the slaughter.

In case you were worried, the producers thought ahead and cast a 15-year-old butcher to show everyone how it’s done. Emilie even comes to watch! Perhaps this was not the best idea, as she ends up barricading herself in the chicken coop again later in the episode.

The kids were cast according to stereotypes

In the opening scene of episode one, Jonathan Karsh announces that the contestants “are every kind of kid imaginable — city kids, country kids, rich, poor, and everything in between.” According to Michael on his Reddit thread, the diversity in casting was meticulously planned (but, like, not in a good way), with contestants being cast to fulfill stereotypes about different groups of Americans. “Greg — a**hole farm boy from Nevada. Alex — smart Asian. Sophia — over-educated, charming neurotic. Me — kid with long hair that likes to say hippie-ish things from Seattle.” He even says he felt as if the producers were “exploiting specific imagery and archetypes” to get what they wanted out of the show.

While this is not exactly out of the ordinary for reality television, says NPR, it once agains brings into question how the audience must navigate what the producers wanted for the program versus how things actually played out.

Production skirted child labor laws

The choice to film in New Mexico was apparently not due to the scenic desert backdrop or Old West charm of Bonanza City. Instead, the allure of New Mexico was the state’s lack of legislation surrounding child labor on TV or film sets. This allowed Kid Nation creators to get creative with their legal language, avoid paying the children for their participation, and keep the cameras on them 24/7. In fact, creator Tom Forman claimed that the kids, “were not working; they were participating,” and that they set their own hours. According to communications professor Mark Andrejevic, such claims were “absurd,” and “in any other industry, this would be called exploitation.”

Since kids are legally required to be in school in most states until they are 18, most sets that involve children for prolonged periods of time have tutors present, allowing the kids to both work in entertainment and obey their state’s education laws. This was not the case with Kid Nation, reports The New York Times, which had no tutor on set, even despite the fact that kids were out of school for six weeks as filming began in April 2007.

After hearing of the production’s potential violations, the state of New Mexico sent a labor department inspector to the set. He claims he was turned away before he could see anything happening in Bonanza City, according to the The New York Times. This would be illegal if true.

Parents signed a bizarre contract

As if those legal loopholes and careful wordings were not enough, parents were also made to sign a detailed 22-page contract that said, among other things, that their children were not actually performing labor of any kind. Instead, they were at summer camp! You know, legally. However, the show did not even file the appropriate paperwork to house that many children for an extended period of time, making their supposed summer fun illegal. Additionally, it was not even the summer when the kids were on set.

According to The New York Times, the contract also said that although the children received a $5,000 stipend for their participation (in addition to having the chance of winning $20,000 each week by receiving a gold star from town council), it would not be acknowledged as payment for services, aka a wage, and the children would not constitute as employees of CBS. This clause essentially excused them from adequately compensating the children, and, along with the summer camp clause, from limiting their time in front of the cameras.

If that wasn’t bad enough, the contract had a slew of other strange sections. For starters, one clause waived liability for “emotional distress, illness, sexually transmitted diseases, H.I.V. and pregnancy,” which came off as quite neglectful since the production involved minors. It also claimed the right to children’s stories “in perpetuity and throughout the universe,” whatever that means, and warned of a $5 million penalty should parents or their children violate confidentiality claims.

Legal action followed

It is perhaps unsurprising that this strange flurry of legal loopholes resulted in attempts to hold the production legally accountable. First, an anonymous letter was sent to several New Mexico state officials that described how a child had been taken to the hospital after consuming bleach while unsupervised, reports The New York Times. Later details revealed that several children had been involved, and the culprit was an unmarked soda bottle filled with bleach that had been left on set.

Another letter also addressed the time that 11-year-old Divad had been burned by cooking grease. Although the producers insist a chef was always in the kitchen with the children, Divad’s parents asserted there was not one in this particular instance.

The complaints prompted a full-scale investigation by the New Mexico attorney general. The Santa Fe County sheriff claimed to find no evidence of criminal activity, though he did forward Divad’s parents’ letter to the civil court. Additionally, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists launched a child abuse investigation. Though nothing came of the various abuse and neglect claims, New Mexico did change their state laws in the wake of the controversy to more explicitly limit the number of hours that children were allowed to work on a television set. This effectively prevented filming of further Kid Nation seasons, at least without future legal cooperation on the part of CBS.

Critical reception and public response

The world was abuzz with Kid Nation talk before the show even came out. The teaser trailer released by CBS before the premiere, which was packed with some of the most dramatic moments from the show, drew a lot of controversy. Entertainment columnists, prominent journalists, and child psychologists alike voiced their ethical concerns with the production. Many Lord of the Flies references were tossed around as people began to make the inevitable comparison. In a listening session with CBS producers (via NPR), one concerned TV critic even asked, “what specific measures were taken to ensure that, for example, Roger doesn’t smash in Piggy’s head with a boulder?”

Parents who allowed their children to go on the show also faced significant criticism, especially those of the youngest cast members. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, communications professor Matthew Smith asked, “Who is ultimately responsible here, the network that dangles the $20,000 prize in front of these parents or the parents who have allowed or encouraged their children to move forward with this situation?”

Ratings for Kid Nation suffered because of the onslaught of bad press. Its first episode fielded nearly 3 million fewer viewers than the show whose time slot it had usurped.

Despite its controversy and subpar ratings, the show earned some critical acclaim. The program received a nomination for “Best Family Reality Show” at the Young Artists Awards and was named the tenth “Top New TV Series” of the year by Time.

Somehow, many enjoyed the experience

Despite all the show’s flaws, some kids and their parents seem to genuinely buy into the experiment by the end. For instance, all four of the children profiled in the Los Angeles Times series about the show’s controversies said they would gladly do the experience over again, even though it was difficult. In fact, all four agreed that the hardest part about the experience was “was leaving Bonanza City and one another.”

Additionally, contestant Laurel and her mom seem to have adopted the summer camp narrative that was so pushed by the show’s creators. In one of the interviews featured in the Los Angeles Times, her mother said, “I don’t think that she or I feel that she worked any of the time she was there… she feels like it was summer camp.” Even Taylor, the beauty queen who refused to do dishes, said the experience taught her something important. “I learned I have to work for what I want.”

While most kids enjoyed their experience, critics of the show have noted the fact that they may have been exploited. Still, it seems like many of the kids fielded some benefits from Bonanza City, mostly in learning the value of hard work and forming a genuine community with their peers.

Where are they now?

The participants are now in their early to mid-20s, and thanks to social media, are talking about their experiences on the show. On her Tik Tok, Savannah confirms the bleach drinking rumor, shares that she didn’t brush her teeth the whole time, and says she would love to continue her reality TV legacy as a cast member on Survivor. Laurel, one of the original town council members, also shares about her experience on Tik Tok. She hopes one day to become a stand-up comedian. DK, the contestant from the bleach drinking incident, has seen success as an actor, appearing in the NBC dramas Chicago PD and Chicago Fire.

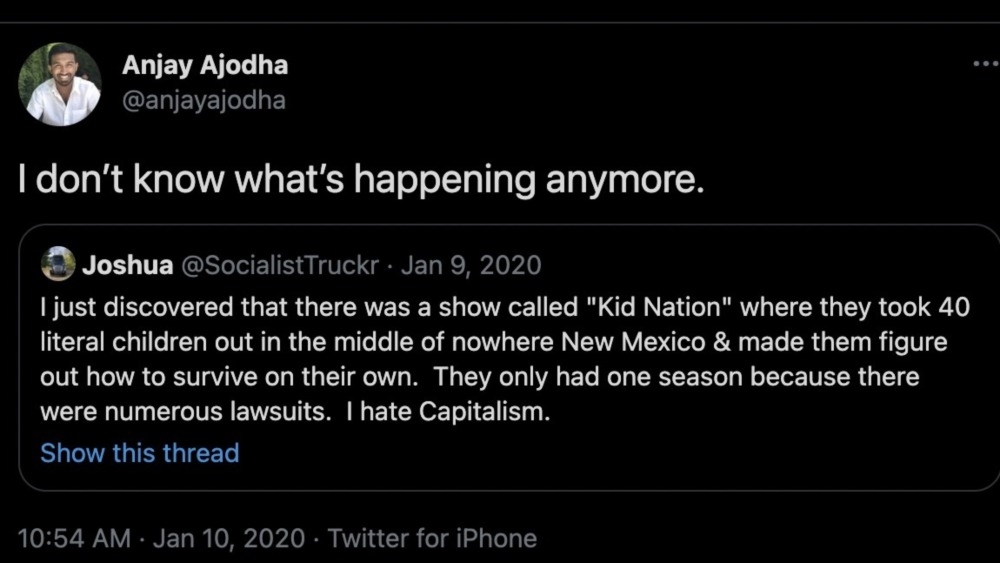

The kids have also ventured past show business. Taylor, the infamous council member with a mean streak, went on to get her masters degree in occupational therapy. One former contestant, Anjay, even works at Microsoft and has previously tweeted about his experience on the show.

The Untold Truth Of Bryant Gumbel

Where Is Frank Zappa Buried?

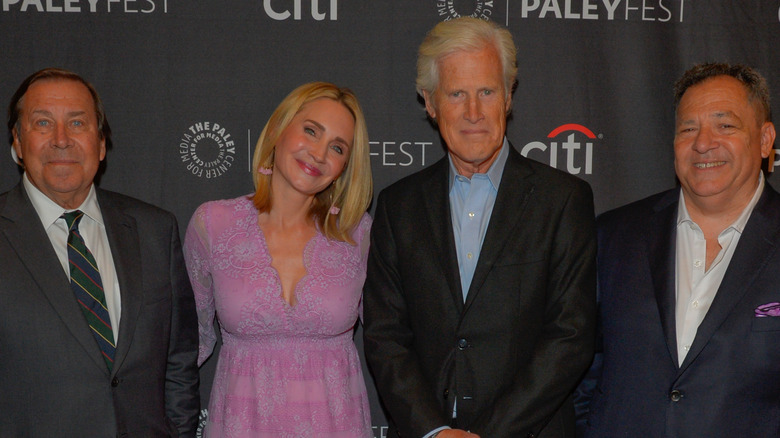

The Untold Truth Of Dateline

The Rolling Stones Album Mick Jagger Thinks Is Overrated

The Tragic Death Of Robin Gibb

The Real Reason Mick Foley Retired From The WWE

The Tragic Death Of John Candy's Father

The Untold Truth Of Pentagram

The Untold Truth Of Sam Cooke

Inside MF Doom's Relationship With Kanye West