The Most Bitter Literary Feuds In History

Literary feuds have captured the imaginations of readers for millennia. Some of the oldest instances go back to Classical Greece, when playwrights such as Aristophanes reportedly included parodic caricatures of their literary rivals in their publicly-performed plays, according to the journal Greece & Rome (via Jstor). And through the centuries, writers have continued to face-off, with literary feuds more common and heated than ever thanks to the internet, where those involved in the dispute can respond to each other in real time to the glee of their respective tribes.

But why do such feuds attract so much attention? Partly, it is down to the fact that, as wordsmiths, those involved have the potential to perform some put-downs of a succinct, professional standard; typically, insults in such feuds drip with what the writer and academic Professor Hua Hsu describes as a “withering brevity” (per Lapham’s Quarterly). But more than this, perhaps it is that book lovers recognize that having the upper hand in the court of public opinion can shape a writer’s legacy, and that — fair or not — such squabbling might be a factor in whose new novel is read 100 years from now, and whose name is effectively forgotten. Here are some of history’s feistiest writerly wrangles.

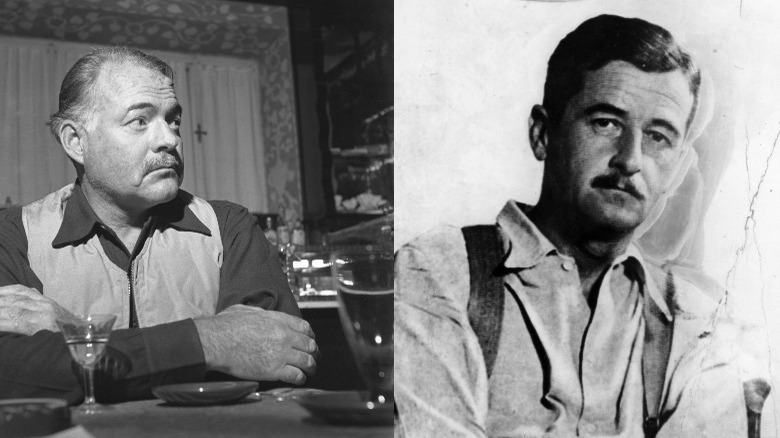

Hemingway and Faulkner's battle for supremacy

Ernest Hemingway (left) became a mythic figure in his own lifetime, a self-described “man without any ambition, except to be champion of the world” (via Google Books) and literary heavyweight who was sure of his abilities as a novelist. His confidence in his literary superiority was implicit in the fact he wrote to William Faulkner in 1947, praising him but also dishing out plenty of writing advice outlining how he might improve. In a letter to a friend, Hemingway described his frustrations with Faulkner’s writing: “He has the most talent of anybody and he just needs a sort of conscience that isn’t there … I wish the christ I owned him like you’d own a horse and train him like a horse and race him like a horse–only in writing” (via Google Books).

But as it turns out, Faulkner didn’t revere Hemingway as much as he’d supposed. In a lecture delivered later in 1947, Faulkner was asked to list the five greatest living writers, excluding himself. Faulkner put Hemingway in fourth place, commenting: “He has no courage, has never crawled out on a limb. He has never been known to use a word that might cause the reader to check with a dictionary to see if it is properly used” (via Britannica). Hemingway responded: “Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words?”

Despite Hemingway’s hubris, it was his rival who officially achieved heavyweight status first: Faulkner won his Nobel Prize in 1949, while Hemingway was only recognized in 1954.

A public spat between Lillian Hellman and Mary McCarthy

In 1980, “The Dick Cavett Show” was the most cultured of TV chat shows, with everyone from John Lennon to Salvador Dali lining up to take a seat on his couch in front of a broadcast audience of millions.

On January 26 of that year, Cavett welcomed as one of his guests Mary McCarthy (right), a seasoned regular on the show. “I always enjoyed having McCarthy as a guest. She was lively, witty, opinionated, and striking on camera,” Cavett wrote in 2002 (via The New Yorker). It had been planned that McCarthy would talk about an underrated young writer of whom she was fond, and as a playful lead-in, Cavett decided to ask her which writers she thought were overrated. But instead of pivoting towards her intended subject, McCarthy answered the question directly, and aimed her ire at her contemporary, Lillian Hellman (left), “who I think is tremendously overrated, a bad writer, and a dishonest writer, but she really belongs to the past … every word she writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.'”

The audience winced, but it would be the producers and McCarthy herself who would soon feel the pain of a huge quarter-million-dollar lawsuit filed by Hellman for libel, followed by an absurd trial in which those involved were called to the stand to discuss the accuracy of Hellman’s fiction. Though the suit rumbled on, Hellman died in 1984, and the complaint was posthumously withdrawn, per The New York Times.

Margaret Drabble and A. S. Byatt's sibling rivalry

Tensions often run high in high-achieving families, especially among siblings. And few literary families sparkle brighter than that of the English sisters known by their pen names as Margaret Drabble (left) and A. S. Byatt. The pair seemingly had greatness thrust upon them … as well as a rivalry that would become the stuff of British literary legend.

According to The Guardian, the sisters’ parents were from working-class backgrounds, the first of their respective families to make it to college. The future writers’ domineering mother reportedly told them when they were infants that “of course, you will go to Cambridge” (via The New York Times). And both did, though it was the elder sister Byatt for whom a career as a writer was a childhood dream. Drabble wanted to be an actress, saying “I didn’t want to [become a writer]. I just happened to write a novel when I was pregnant and had nothing to do.” Yet Drabble had the first success, with the 1963 publication of “A Summer Bird Cage” arriving three years before her sister’s debut. Since then, the two have been compared to each other relentlessly, making theirs a fraught relationship (via Slate).

“It is just an incomprehensible relationship to me,” said Drabble. “I was the little sister who thought she [Byatt] was clever and wonderful, and she thought I was in the way all the time. I think it is so normal for an elder sister to resent the younger one. It’s just unfortunate that we were interested in the same things” (via The New York Times).

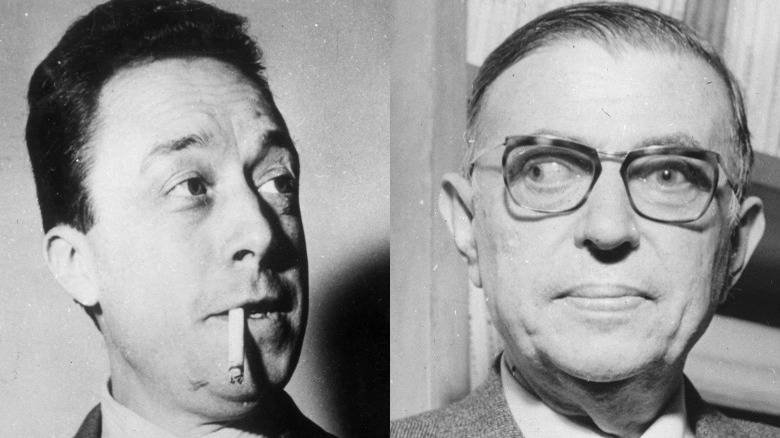

Albert Camus' success irked Jean-Paul Sartre

It is sometimes surprising when people say they don’t get on with each other because they are “too alike.” But at first glance that seems to have been the trouble with two of existential philosophy’s main players: Albert Camus (left) and Jean-Paul Sartre (right), who after enjoying a long and fruitful friendship had a very public falling out in the summer of 1952, according to Spiegel International.

Aeon reports that the two intellectuals first met in Paris, during the German occupation. Both were already famous, and they had read and reviewed each other’s work, showing a mutual respect (per University of Chicago Press). When World War II came to an end and Paris was liberated and free to once again become a bastion of European literature and freethinking, the friendship between the two blossomed, and they quickly became mutual champions and confidantes. Both Camus and Sartre were at the vanguard of modern thought; per the same source, their common search for human freedom and social justice made them philosophical and political comrades.

But as the post-war left split along tribal lines between communism and socialism, so did Sartre and Camus, aligning themselves with each ideology respectively. Meanwhile, Camus grew to outshine his former philosophical sparring partner in terms of popularity and success; he was charming and good-looking, and his novels, especially “The Plague,” vastly outsold those of Sartre.

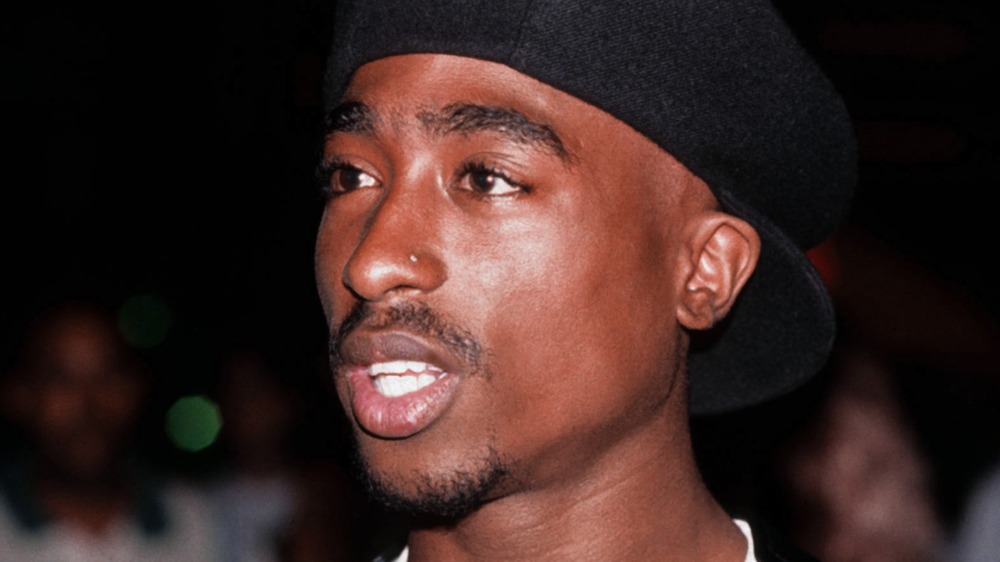

Carl Jung's rift with Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud (bottom left) and Carl Jung (bottom right) are today remembered as the most influential figures in how we have come to understand the human mind. And though many of their medical ideas have since dropped away from mainstream psychology, much of what they wrote — such as Freud’s conception of the mind as an id, ego, and superego, and Jung’s belief that our collective imagination is populated by a cast of ‘archetypes’ — remain central to discussions of the human mind in popular culture.

Freud and Jung first communicated by letter, before eventually meeting in 1907. The two hit it off, and spent a marathon 13 hours in conversation, expounding on their shared beliefs and unconventional ideas. Jung saw in the older man a fitting mentor and guide for his own free-thinking; Freud saw Jung as a potential mainstream champion of psychoanalysis who could help to overcome the antisemitic criticism that Freud’s beliefs were those of a niche Jewish intellectual cult, according to Aeon.

By 1913, however, the relationship between the two was becoming strained, and their friendship ruptured during a conference in which Jung publicly laid out the foundations of what would become his own school of psychoanalysis which would rival that of Freud. The moment was highly oedipal in nature, with Jung — willing until then to exist in the shadow of his mentor — effectively rebelling to “kill” his father figure, Freud, and forge his own path in psychoanalysis and formulating his own ideas.

Byron and Keats were very different romantics

To some, the phrase “Romantic poet” means a swashbuckler who charms with his verse and feats of heroism: that is the image of Lord Byron (left), whose semi-autobiographical epics such as “Don Juan” made him a major celebrity in his own lifetime. But to others, Romantic poets are tender individuals, who recline in nature for hours, letting the world around them stir their sensitive emotions: this caricature resembles John Keats (right), who, while he had his admirers, struggled financially throughout his life, while many critics misunderstood and slated his poetry, according to English History.

The two were known to dislike each other, as is evidenced by Keats’ September 1819 letter to his brother George, which reads: “You speak of Lord Byron and me — There is this great difference between us. He describes what he sees — I describe what I imagine – Mine is the hardest task.” Less politely, Byron criticized Keats thusly: “He is always frigging his Imagination… this miserable Self-polluter of the human mind” (per The Guardian).

But though on first look it may appear that the differences between the two men were poetical in nature, their rivalry was also spurred on by good old-fashioned class differences, with Byron and much of his aristocratic circle dismissing Keats as merely a minor “Cockney” poet who failed to possess the breeding required for epic verse. For his own part, Keats privately claimed that Byron was only prominent in poetic circles because of his upper-class background, and that, simply put, he lacked talent.

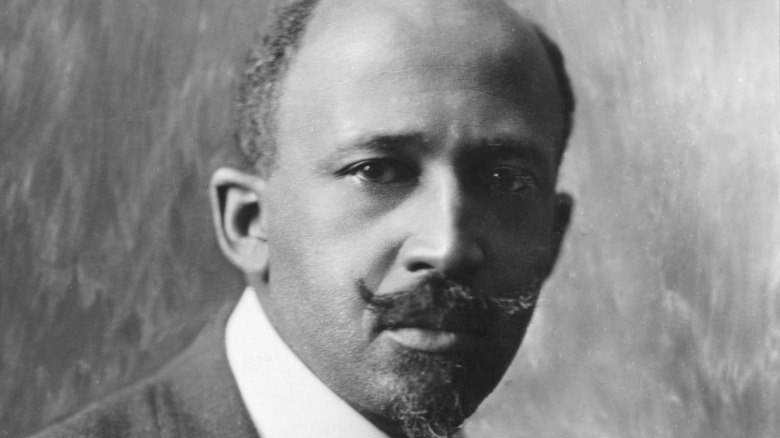

Zora Neale Huston and Langston Hughes' ill-fated collaboration

Just as famous rock bands can break up as friendship is tested by disagreements and cabin fever, literary figures who collaborate together can also have spectacular bust-ups. One of the most famous feuds in American letters is that between Zora Neale Huston (left) and Langston Hughes (right), whose eventual animosity matched in case the intensity of their one-time friendship.

Both major figures in the Harlem Renaissance, Alice Walker has claimed that: “Each was to the other an affirming example of what black people could be like: wild, crazy, creative, spontaneous, at ease with who they are, and funny” (per The New York Times).

Though Huston and Hughes never claimed to be anything more than friends publicly, their falling out was more explosive than that of most love affairs. Per The Time Literary Supplement. They had first met in New Orleans in 1925, and by 1930 were collaborating on a play, “The Mule-Bone,” an adaption of a Hughes short story. However, critics agree that it was Hurston who did the majority of the work on the play, and that frustrations grew until, per the same source, the writers descended into an “epic custody battle” over the play, according to the same source. After a lengthy legal struggle, it was agreed that performances of the play were banned until after the deaths of both parties.

Tibor Fischer's brutal takedown of Martin Amis

Martin Amis (left) emerged as a darling of the British literati thanks to his caustic early work such zeitgeist-y yuppie-baiting novel “Money” (1984), while mid-career high points such as the technically adept “Time’s Arrow” (1991) sealed his reputation as one of Britain’s foremost writers. But British authors have a long history of trading barbed comments, with wars of words often becoming a sort of blood sport for the country’s incestuous literary scene. By the early 2000s, the critics were increasingly split over the quality of Amis’ recent work, and many were more than willing to take a swipe at an author whose powers were seen to be declining.

One of these was Tibor Fischer (right), a contemporary of Amis’ and a comic novelist himself who in 2003 lambasted Amis’ latest offering, “Yellow Dog,” as “not-knowing-where-to-look-bad”, and compared his shock at the poor quality of Amis’ writing as akin to finding “your favorite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating” (per The Guardian).

Amis willingly responded — though perhaps not with the relish that Fischer displayed in his hatchet job — stating in an interview shortly after the review was published: “Tibor Fischer is a creep. Oh yeah … and a fat arse.” (via The Telegraph) But by then, one of the decade’s most memorable literary putdowns had already been unleashed.

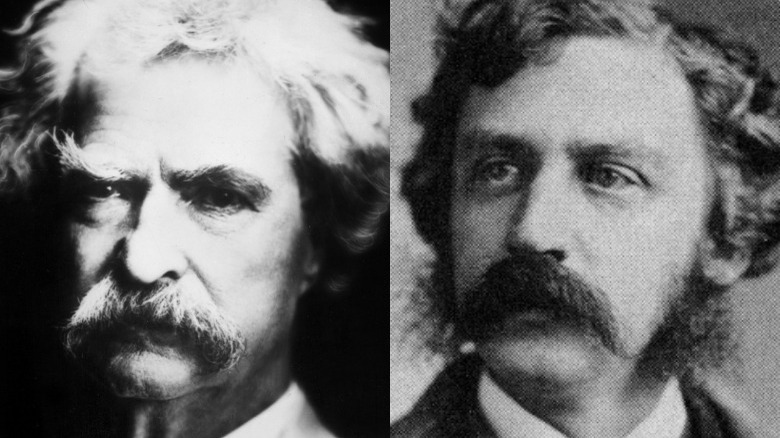

Mark Twain's merciless pursuit of Bret Harte

The world’s appreciation of Mark Twain’s genius has grown and grown in the years since his death, to the point at which in the 21st century he is held up as the patron saint of American comedy, with the nation’s most prestigious comedy prize named after him (per The Kennedy Center).

But Twain (left) wasn’t always the pure comedic soul that we consider him to be today, as evidenced by his atrocious treatment of fellow writer Bret Harte (right). When he first befriended Harte, Twain was the junior figure, though the commonalities between Twain’s early work and Harte’s “pioneer fiction” made collaboration between the two writers a natural development, according to Books Tell You Why. Ever-willing commentators of societal wrongs, Harte and Twain began work on a play, “Ah Sin,” which the duo envisaged as a critique of the wave of anti-Chinese rhetoric that swept among American workers in the 1860s.

However, the two men clashed repeatedly over their script, with Harte eventually removing himself from the project before a performance had even been given. Twain was furious, and in the weeks that followed began a smear campaign against his former friend, writing anonymously in national newspapers to call into question Harte’s moral character. Twain even continued to rage against Harte — in particular his inability to repay loans — years after Harte’s death, according to the Mark Twain Journal (via Jstor).

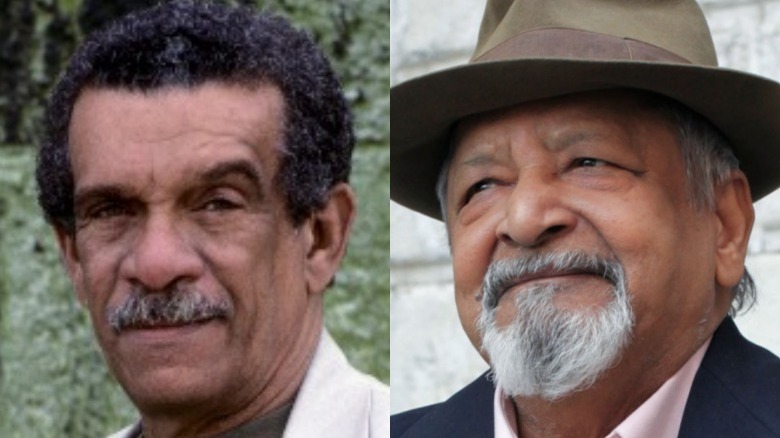

Derek Walcott got his revenge on V. S. Naipaul in verse

Even the most cerebral authors with decades of experience behind them find it difficult to take criticism lying down. By the late 2000s, St. Lucian poet Derek Walcott (left) was one of the greatest and most celebrated poets on the planet. Then in his late 70s, Walcott’s poetry, such as the beautiful “Love After Love,” was widely taught in schools and colleges, and Walcott had already been awarded literature’s greatest honor, the Nobel Prize, in 1992. But according to the New Yorker, Walcott’s hackles were raised when in 2007 the Trinidadian novelist V. S. Naipaul (right) criticized Walcott’s later work by claiming Walcott had become “a man whose talent has been all but strangled by his colonial setting.”

Walcott’s revenge took the form of a very public roasting of Naipaul, in verse form, of course. At the 2008 Calabash International Literary Festival, Walcott unveiled a new poem, “The Mongoose,” and the poet made clear the target of his vitriol; “You’ll recognize Mr. Naipaul,” Walcott reportedly told the audience according to The Guardian.

“I must have been bitten/ I must avoid infection/ Or else I will be as dead/ As Naipaul’s fiction,” read one representative stanza, while elsewhere Walcott derided his critic as a “rodent in old age” and a “burnt out comic” (per The New Yorker).

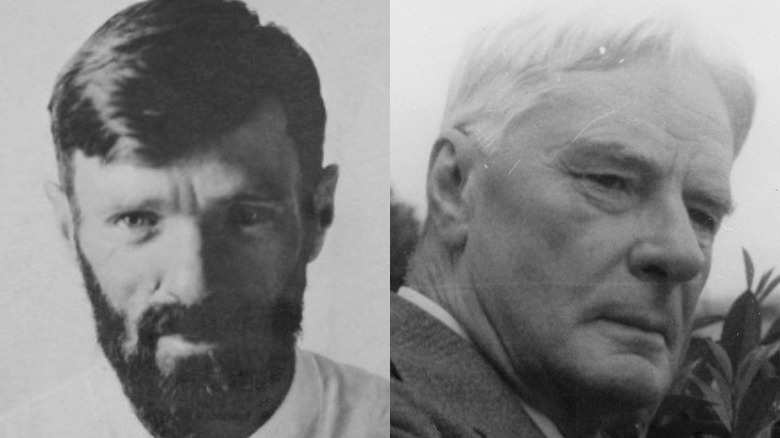

D. H. Lawrence's fictionalizing went too far for Norman Douglas

In the 1920s, the novelists D. H. Lawrence (left) and Norman Douglas (right) were close friends and accomplices, whose fiery writings challenged traditional tastes and caused a continuous stir among Britain’s literati. But the two writers went to war with each other following the death of their common friend, an American traveler and journalist named Maurice Magnus, and Lawrence’s being employed to write the introduction of Magnus’ posthumously-published final memoir, “Memoirs of the Foreign Legion.” According to The D. H. Lawrence Review (via Jstor), the piece took the form of a long narrative, and included thinly-veiled but highly critical portrayals of both Douglas and the late Magnus.

In response, Douglas published a pamphlet, “D. H. Lawrence & Maurice Magnus: A Plea For Better Manners,” which hotly contested the portrayal of Magnus, per the D. H. Lawrence Review, and claimed that Lawrence had with a “novelist’s touch” misrepresented the truth of his relationship with Magnus, and suggested he had turned against his late friend as Magnus had owed him money at the time of his death. Douglas’ pamphlet was considered a mic drop moment in literary circles, and effectively exploded his friendship with Lawrence.

The Imagist poet and Lawrence ally Richard Aldington sadly deplored the affair, claiming that “warfare between two such free spirits and great writers as Norman Douglas and D. H. Lawrence was a misfortune for both literature and themselves,” per the same source.

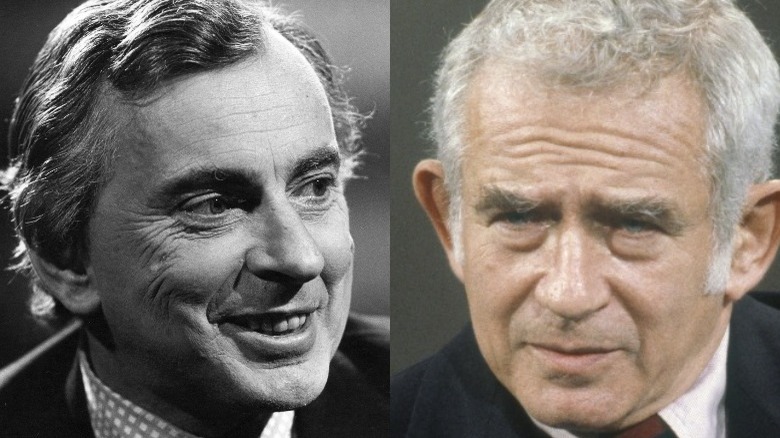

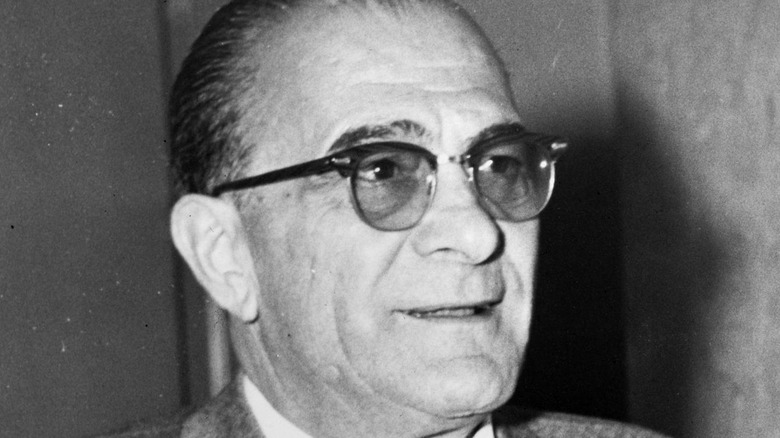

Gore Vidal's knockout blow for Norman Mailer

Gore Vidal (left) and Norman Mailer (right) had a rocky association that lasted the best part of 50 years. It began around the time that Mailer was at his most famous, when his 1948 novel, “The Naked and the Dead,” made him a household name, according to Entertainment Weekly. Vidal had already published books of his own but had failed to reach such heights as Mailer had, and the two writers began a troubled friendship driven by ambition and rivalry more than respect and affection.

And in 1971, relations between the two rivals hit a nadir, which played out publicly in incidents that have become the stuff of American literary folklore. Amid a fierce debate among American public figures about the rise of feminism, Vidal and Mailer became engaged in a feud over their opposing beliefs, with Vidal skewering Mailer in an article that compared the writer to Charles Manson, saying they both saw “women as at best, breeders of sons; at worst, objects to be poked, humiliated, killed,” per the same source. Mailer attempted to take Vidal to task on “The Dick Cavett Show,” but only succeeded in alienating the other guests as well as the host as he brazenly declared his own moral and intellectual superiority.

The two clashed as functions throughout the seventies, until in 1977 Mailer punched Vidal at a New York party, according to The Guardian. After the initial shock, Vidal is said to have uttered the immortal line: “Norman, once again words have failed you.”

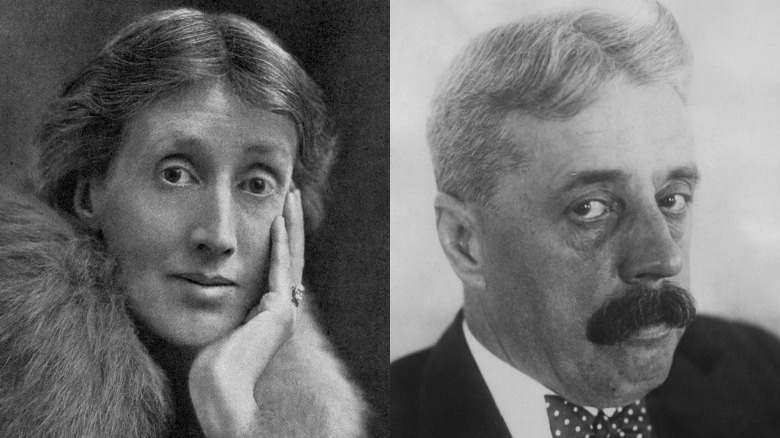

Virginia Woolf buried the past, specifically Arnold Bennett

Intergenerational jealousy is alive and well today — how else do you account for all the “OK boomer” memes and lazy stereotypes about the work ethic and financial habits of millennials and Gen Z? — but it has long been an aggravating factor in some of history’s most vicious literary battles.

Take, for example, the bitterness that eventually grew between Arnold Bennett (right), a prolific British author born in 1867, and Virginia Woolf (left), a now-iconic modernist writer some 15 years his junior. According to Debating Modernism, it was Bennett’s dismissal of Woolf’s powers of characterization in her just-published novel “Mrs. Dalloway.” Little did Bennett know, he was waking a dragon. Woolf’s response, “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown,” was a searing riposte to Bennett which dismissed the whole literary mode of his Edwardian generation, and which effectively undid his legacy — unfairly or not — in a stroke.

As noted in the journal Novel: A Forum of Fiction, Bennett’s vast fame eclipsed that of his younger sparring partner, but Woolf’s essay seems to have killed his reputation off for the generations that followed; “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown” is still widely studied, while, per the same source, all eight books of Bennett’s criticism are currently out of print. Similarly, his novels remain little read today.

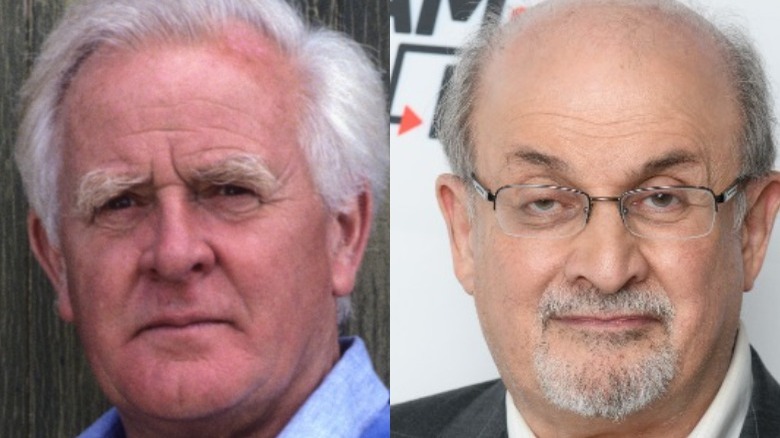

John le Carre and Salman Rushdie's regrettable feud

You know that a literary feud is really boiling over when the literature writers for both The Guardian and The New York Times reach for the adjective ‘vituperative,’ and that’s just what happened in the case of John le Carre (left) vs. Salman Rushdie (right), yet another case of two British authors who famously enjoy more than their fair share of their country’s famous verbal wit descending into schoolyard insults and damaging their own reputations in the process. And in stereotypical writerly fashion, many of the insults were slung via the classic forum of a newspaper’s letters page.

The row erupted when le Carre, responding to a negative review of his 1996 book “The Tailor of Panama” that criticized his portrayal of a Jewish character as potentially antisemitic. When le Carre wrote a response claiming he had been the victim of “political correctness,” Rushdie waded in, chastising his fellow writer for failing to support him when he to a greater degree caused offense for his critique of Islam in his book “The Satanic Verses,” which led to a fatwa being put on his head and the novelist going into hiding.

Le Carre claimed that Rushdie was being “arrogant” and “self-canonizing,” and that his longtime notoriety had gone to his head, while Rushdie called le Carre a “pompous ass” and explained le Carre’s earlier reluctance to defend free speech due to his being “semi-literate.” The two eventually reconciled over a decade later, with both showing remorse for the spat, according to The Guardian.

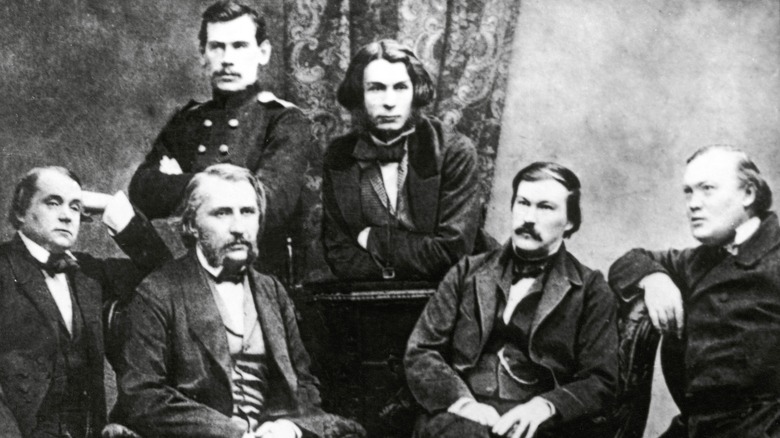

Dostoevsky vs. Turgenev vs. Tolstoy

In the 19th century, Russian literature was populated by giants, and, as such, when they went at it with each other the resulting quarrels were spectacular. In the case of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ivan Turgenev (second left, bottom), and Leo Tolstoy (second left, top), the stakes were, of course, their own literary reputations. But as widely-read commentators of a country that was continually looking to examine and come to terms with itself, the greater prize was to be the leading light who influenced how Russian life was ultimately characterized.

In an 1867 letter to a friend in which he discussed Turgenev’s latest novel, “Smoke,” Dostoevsky ranted that: “All these wretched liberals find their principal pleasure in abusing Russia” (per Russia Beyond). Dostoevsky was a nationalist and conventional in his views of how society should operate, while with his classic novel, “Fathers and Sons,” Turgenev single-handedly outlined a subversive attitude of rebellion that came to be known as nihilism (per Britannica).

The writers sniped at each other endlessly, but they arguably each had a bigger fish to fry in Tolstoy; Dostoevsky clashed with the younger writer over matters of foreign policy, according to Open Democracy, while Turgenev enjoyed a fraught friendship with Tolstoy, on one hand holidaying with him and on the other losing patience with one another so entirely that they came close to dueling, according to the New York Public Library.

How Marquis De Lafayette Helped Create A New Dog Breed

The Surprising Amount Of Money Someone Once Paid For Hitler's Boxers

The Truth About The Person Who Photographed The Titanic Disaster

A Day In The Life Of A Prisoner At Guantanamo Bay

Why Urine Was Once Used To Make Gunpowder

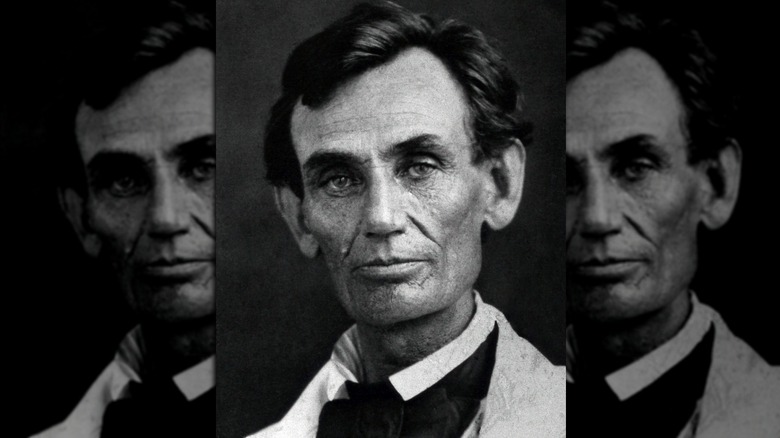

What Did Abraham Lincoln Look Like In Color?

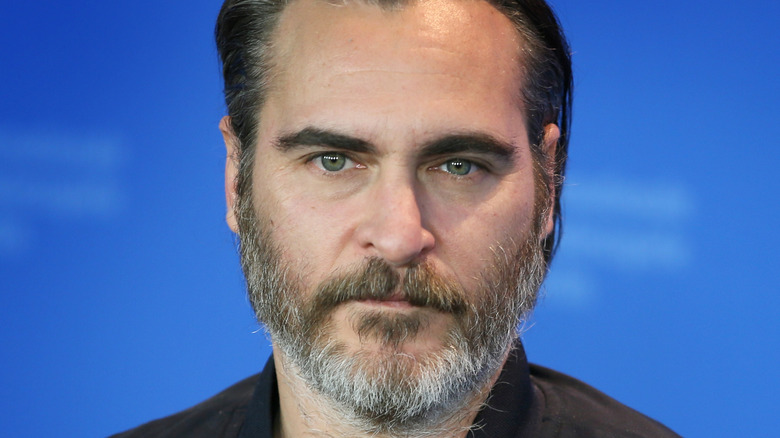

This Was Joaquin Phoenix's Experience In The Children Of God Cult

Who Divided The Bible Into Chapters And Verses?

Messed Up Things That Happened During The Mexican-American War

How Dr. Joseph Bell Became The Real-Life Sherlock Holmes