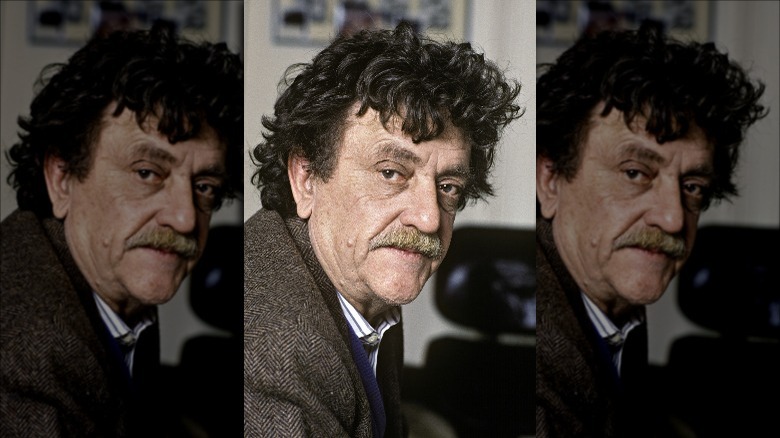

The Tragic Life Of Kurt Vonnegut

“So it goes.”

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. made these three words into a recurring motif in his most famous book, “Slaughterhouse-Five,” first published in 1969. The phrase first appears on page one, after Vonnegut tells how the mother of his “old war buddy,” Bernard V. O’Hare, died “incinerated in the Dresden fire-storm.” Thereafter, “so it goes” becomes a refrain for every death in the entire book … and has become indelibly symbolic of the work and worldview of Vonnegut in the decades since the book brought him international fame.

Many critics have interpreted this most famous phrase from Vonnegut’s oeuvre as a reflection of his resigned aloofness. However, the Booker Prize-winning author Salman Rushdie argues that the phrase is “deeply ironic. Beneath the apparent resignation is a sadness for which there are no words” (per the New Yorker). Seemingly flippant at first, Vonnegut’s repeat use of the phrase whenever death is encountered flags up the fact that scenes of death permeate the story; it is so widespread — and inevitable — that the reader in fact becomes increasingly conscious of it: rather than “letting it go,” we become aware that the world is imbued with tragedy … as Vonnegut’s own life attests.

The downfall of the Vonnegut family

On the title page of “Slaughterhouse-Five,” below the name Kurt Vonnegut Jr., follows a brief biography of the writer and his relationship to the Dresden fire-bombing, which described him as “a fourth-generation German-American now living in easy circumstances.”

The circumstances of Vonnegut’s early life were also easy initially; his father, Kurt Sr., was a famous architect, while his maternal grandfather, Albert, was the owner of a brewery that made him a famous face as one of the wealthiest people in the Vonnegut’s hometown of Indianapolis, Indiana (pictured), according to “And So It Goes,” the 2011 biography by Charles Shields. The wedding of Kurt Sr. to Vonnegut’s mother, Edith, in November 1913 was a lavish affair.

Vonnegut’s cultured family treated him to what Shields describes as a “hothouse education” after his birth in November 1922 — but trouble brewed as the years rolled on. When the Great Depression began following the stock market crash of 1929, Kurt Sr. struggled to find work, while Edith’s family fell on hard times as a result of prohibition. Suddenly, the previously affluent Vonneguts suddenly found themselves in relative poverty.

The tragic death of Kurt Vonnegut's mother

Edith Vonnegut was heartbroken by the loss of her family’s fortune, and as the years went on her unhappiness spiraled into a deep depression which permanently altered her personality and made her abusive towards her husband and children. “When my mother went off her rocker late at night, the hatred and contempt she sprayed on my father, as gentle and innocent a man as ever lived, was without limit and pure, untainted by ideas or information,” Vonnegut recalled (via The New York Times).

In 1944, Vonnegut — who was at the time training to serve in the U.S. Army — returned to his family home in Indianapolis. It was Mother’s Day. Tragically, Vonnegut was greeted by the terrible news that his mother had died by suicide. It was an event that profoundly affected the young man, and which he evoked often when discussing his own depression later in life.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Vonnegut dropped out of college to join the Army

Kurt Vonnegut Jr.’s early life and education was, like that of his father, geared towards pragmatic success. He went to Cornell University — the place where his contemporaries, the soon-to-be-famous Beat Generation, first met and exchanged ideas — but rather than a humanities degree Vonnegut studied biochemistry, at the behest of his father. Vonnegut had worked on the student paper, the Echo, when he was at high school, and at university continued to keep his hand in journalistic writing in addition to his studies.

However, by his own admission, Vonnegut was a “lousy student” (per the Vonnegut Library). Throughout his college years, World War II was raging in Europe, and as the conflict reached its endgame it appeared imminent that young men such as Vonnegut would soon be drafted in. He enlisted, and after a short training period was sent to serve as a U.S. Army private in Dresden, Germany.

Vonnegut was captured during the of the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge was the last German offensive of World War II, a surprise attack on Allied territory around Antwerp that began on December 16, 1944. Three days later, Private Kurt Vonnegut Jr., newly arrived in Germany, was captured. Per the Smithsonian Magazine, Vonnegut’s family in Indianapolis received a telegram informing them only that he was now “missing in action.”

Five months later, Vonnegut, now in a repatriation camp, was finally able to contact his family and tell them he was alive. However, the details he shared of his capture and the trials of him and his fellow prisoners of war — herded to camps in cramped, unheated boxcars — were still harrowing: “On Christmas Eve the Royal Air Force bombed and strafed our unmarked train. They killed about 150 of us. We got a little water Christmas Day and moved slowly across Germany to a large P.O.W. Camp in Mühlberg, south of Berlin. We were released from the box cars on New Year’s Day. The Germans herded us through scalding delousing showers. Many men died from shock in the showers after 10 days of starvation, thirst, and exposure. But I didn’t.” (via Open Culture)

Vonnegut explained that, according to the Geneva Convention, officer-class soldiers were not required to work while kept as prisoners of war. “I am, as you know, a private,” he blackly wrote. As such, he was taken to Dresden to perform labor at a workcamp.

Kurt Vonnegut and the Dresden fire-bombing

In their 2007 obituary of Kurt Vonnegut Jr., The New York Times described his next experience as a prisoner of war as the “defining moment of his life.” It is hard to disagree. As described by the National WWII Museum, Vonnegut and his fellow prisoners were given work in a repurposed malt-syrup factory, the long hours made intolerable still by the minimal food they were afforded by their brutal prison guards. The winter was one of the coldest in recent memory.

“On about February 14th the Americans came over, followed by the R.A.F. Their combined labors killed 250,000 people in 24 hours and destroyed all of Dresden — possibly the world’s most beautiful city, ” Vonnegut wrote (per Open Culture). Vonnegut’s workcamp detachment was kept safe in a deep basement for days on end as the bombardment and subsequent fire-storm raged.

In the days and week that followed, Vonnegut and his fellow P.O.W.s were put to work excavating the charred remains of troops and civilians who had died in the mindless bombing. (History reports that the attack was mainly on civilian and cultural targets, an intentional “terror campaign”). As the protagonist of “Slaughterhouse-Five,” Billy Pilgrim — who, like Vonnegut, survives the firestorm — describes it, Dresden after the destruction resembled the moon.

Kurt Vonnegut faced multiple family tragedies

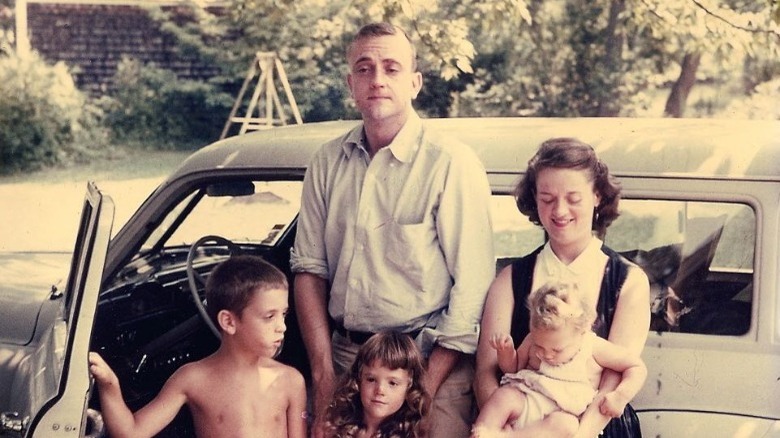

Despite the traumas of Dresden, on his return to the U.S. Kurt Vonnegut Jr. was able to quickly set about building a life for himself alongside his growing literary ambitions. Within months, Vonnegut was married to a woman named Jane Marie Cox, whom he knew from high school, per Biography, and with whom Vonnegut would soon have three children.

The couple moved to Chicago, where Vonnegut enrolled in college and found work as a reporter for a local paper, according to the Kurt Vonnegut Society. Though Vonnegut was beginning to write more and more, his first concern was supporting his family. Relocating to New York, Vonnegut became a publicist for General Electric from 1947 to 1950, a job which Vonnegut noted brought him close to scientists and engineers and which informed much of the science fiction-infused writing that followed (per The New Republic).

Vonnegut continued to move between job but eventually made the move to full time writing. However, in the 1950s his family was set to experience another trauma: in 1958, Vonnegut’s sister, Alice, and her husband, James, both died within a 48-hour period, of cancer and in a car crash respectively (per the Kurt Vonnegut Society). They left behind four boys, three of whom the Vonneguts adopted, heaping greater pressure on the budding writer to gain greater success.

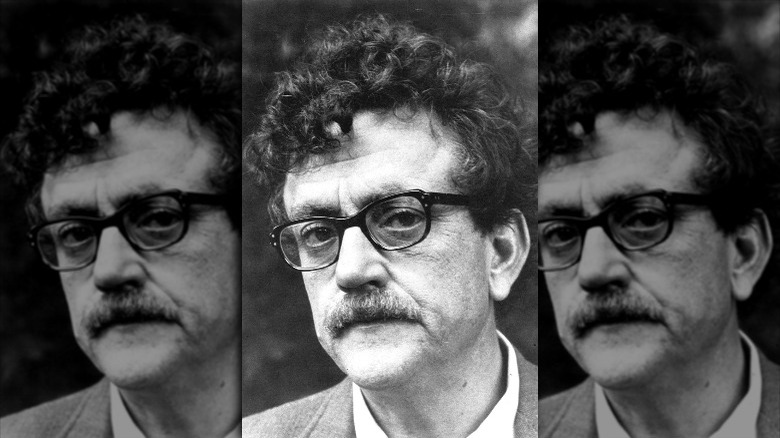

Vonnegut confronted his war trauma to write his most famous novel

The specter of the horrifying scenes that Kurt Vonnegut witnessed as a prisoner of war in Dresden in the final months of World War II haunted the writer throughout his career and the writing of his early novels, “Player Piano” (1952), “The Sirens of Titan” (1959), and “Cat’s Cradle” (1963). But although the black comic treatment of tragedy and the strong pacifist leanings that would come to define his oeuvre were already richly present in these novels, Vonnegut found himself unable to deal with his war experiences directly for many years.

According to the Independent, following the publication of “Cat’s Cradle” Vonnegut was thinking of quitting full time writing and seeking more regular work to support his growing family: “I had gone broke, was out of print and had a lot of kids,” Vonnegut later recalled. He then enjoyed two pieces of good fortune: first, he was given engaging, creative work as a teacher at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, which provided him with a much needed regular income. Second, he was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, which allowed him to return to Europe to research the details of the war in which he had served two decades earlier. As Vonnegut himself details in the opening chapter of the book, he was finally ready to confront and write about his horrifying experiences, and the result was “Slaughterhouse-Five,” which became a bestseller and made Vonnegut a household name.

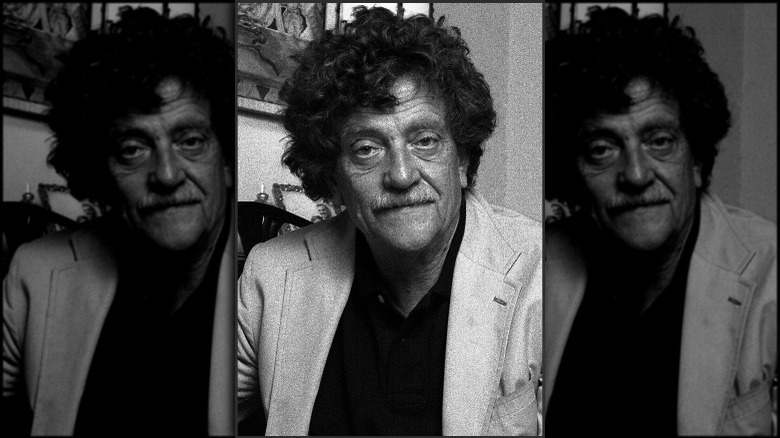

The breakup of Kurt Vonnegut's marriage

Kurt Vonnegut was now a major celebrity, with “Slaughterhouse-Five” making him a darling of the growing anti-war movement that emerged in response to U.S. intervention in Vietnam. But while the writer was enjoying the success that he had been working towards for a quarter of a century, his private life was beginning to fall apart.

Vonnegut had been married to his wife, Jane, since 1945. According to the New Yorker, the two had known each other since kindergarten, and had been childhood friends before hitting off a romantic relationship while Vonnegut was at Cornell. The same source details how Jane had been a key influence of Vonnegut throughout his early career, a sounding board for his ideas and a figure who would encourage him amid the scores of rejections he received when starting out.

But now Vonnegut was barely home, and when he was the two argued constantly. Per The Guardian, Jane had developed a growing interest in Christianity, and her newfound spirituality clashed with Vonnegut’s out-and-out atheism. The couple effectively split in 1970, and endured a painful dissolution of their marriage before eventually divorcing in 1979 (per the Daily Beast). The same year, Vonnegut married the photographer Jill Krementz, who would remain his partner for the rest of his life.

Kurt Vonnegut's suicide attempt

In the years following the success of “Slaughterhouse-Five,” the Vonnegut family was also rocked by mental illness. On Valentine’s Day, 1971, Kurt and Jane Vonnegut’s son, Mark, was committed to Hollywood Psychiatric Hospital, Vancouver, where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia (via The New York Times). By 1975, Mark had recovered sufficiently to write about his experiences, and he promoted the book alongside his father, who spoke about his guilt. “I thought perhaps he would never recover … I’m deeply relieved that I’m not to blame for his insanity. You can make other persons insane by treating them badly.”

But Vonnegut’s own mental health was beginning to deteriorate. In a 1973 interview with Playboy, Vonnegut described how depression led to him sleeping round the clock, and that he experienced “periodic blowups” in which he would lash out at those around him (via Scraps From The Loft). He was prescribed Ritalin, he tells the interviewer, claiming: “It worked. It really impressed me … I was so interested that my mood could be changed by a pill.”

But Vonnegut’s struggles with depression continued. In 1984, he attempted to die by suicide at his New York home. “I decided it was finally time,” he said, according to the Washington Post. Thankfully, Vonnegut was found, and was taken to recover at a nearby hospital.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

'Can I go home now?'

As the decades rolled on, Kurt Vonnegut continued to write, though by the end of the 20th century he had turned away from fiction. His last novel, “Timequake,” was published in 1997 to mixed reviews, similar to the lukewarm reception received by much of his work in the ’80s and ’90s (via the Daily Beast). Vonnegut had previously abandoned the novel in favor of turning his hand to plays, and by the turn of the millennium he was writing journalism almost exclusively.

Vonnegut was still a popular public figure and speaker, but as he entered old age his growing world-weariness came to consume him. In 2006, Vonnegut, then 83 years old, gave an interview to Rolling Stone, in which he compared his mentality — he readiness for death — to waiting to be discharged at the end of World War II: “The Army kept me on because I could type, so I was typing other people’s discharges and stuff. And my feeling was ‘Please, I’ve done everything I was supposed to do. Can I go home now?’ That’s what I feel right now. I’ve written books. Lots of them. Please, I’ve done everything I’m supposed to do. Can I go home now?” (via Notable Quotes).

The death of Kurt Vonnegut

“I’ve been smoking Pall Mall unfiltered cigarettes since I was 12 or 14,” Kurt Vonnegut claimed in an interview. “So I’m going to sue the Brown & Williamson Tobacco Company, who manufactured them. And do you know why? Because I’m 83 years old. The lying bastards! On the package Brown & Williamson promised to kill me” (via Time).

As it turned out, Vonnegut didn’t have much longer to wait. But however much Vonnegut may have told the world he was ready to go — and the grand old age he got to, despite being a lifelong smoker — the circumstances of his death were still tragic.

On April 11, 2007, Reuters reported that the great writer had died in hospital, where he had been cared for following a fall outside his New York home some weeks earlier. Reportedly, his death was the result of severe brain injuries he had suffered during the fall. He was 84.

The enduring popularity of Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut enjoyed telling the story of his return to his family’s hometown of Indianapolis following “Slaughterhouse-Five” becoming a bestseller. He claimed that he was expected to be greeted by a rapturous reception — instead, he signed only a few copies of his book during a long signing session at a local bookstore, and they were mainly for family and friends.

But in the years since his death, the popularity of his work — especially “Slaughterhouse-Five” — has endured, and his writing is treasured as some of the most important novels of the century. On the 50th anniversary of the release of “Slaughterhouse-Five,” the Kurt Vonnegut Museum & Library announced that it was partnering with Penguin Random House and the Indiana State Library to supply 86,000 copies of Vonnegut’s greatest novel to every sophomore in the state of Indiana.

His body of work continues to grow — numerous posthumous works have been published in recent years, including “Armageddon in Retrospect,” a collection of essays edited by Vonnegut’s son, Mark — as does academic interest. His writing is now discussed as a major achievement of American postmodernism. Not that Vonnegut himself would give that much thought; as he once so memorably explained: “I tell you, we are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you different” (via BrainyQuote).

This Is The Best And The Worst Path You Can Choose In Netflix's Escape The Undertaker

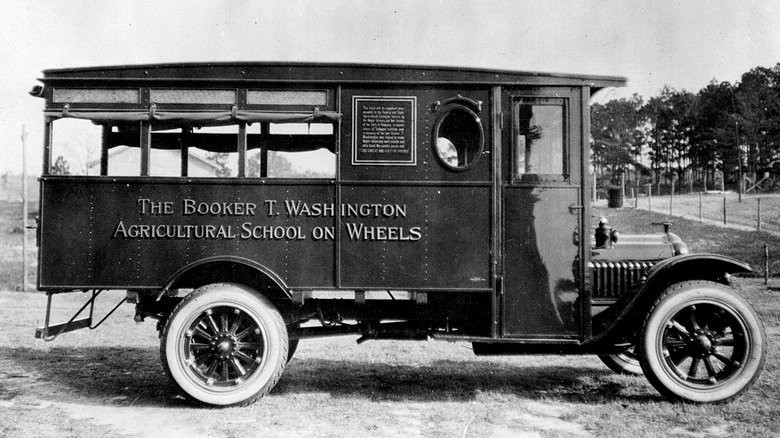

The Truth About George Washington Carver's School On Wheels

The Mythology Of Demeter Explained

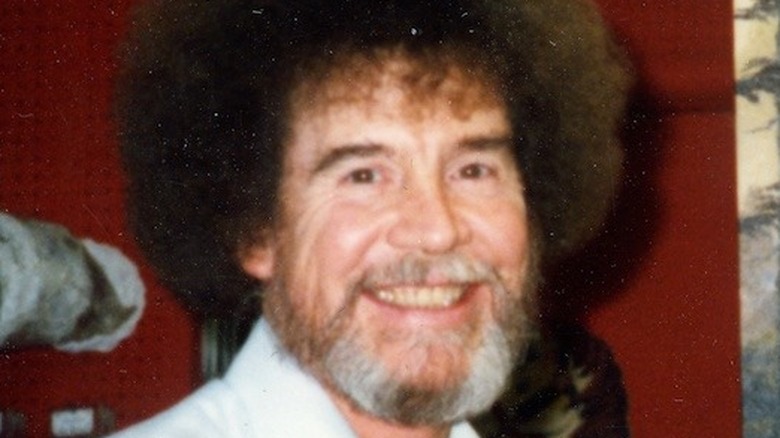

How Long It Took Bob Ross To Film An Entire Season Of The Joy Of Painting

The Messed Up Truth About The Southern Redemption Movement

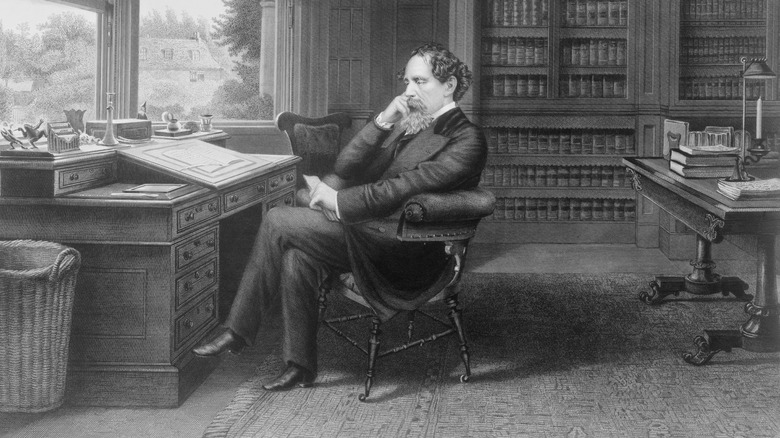

The Tragic Death Of Charles Dickens' Children

The Truth About Dan And Betty Broderick's Children

The History Of The Golem Explained

The Most Dangerous Drugs Throughout History

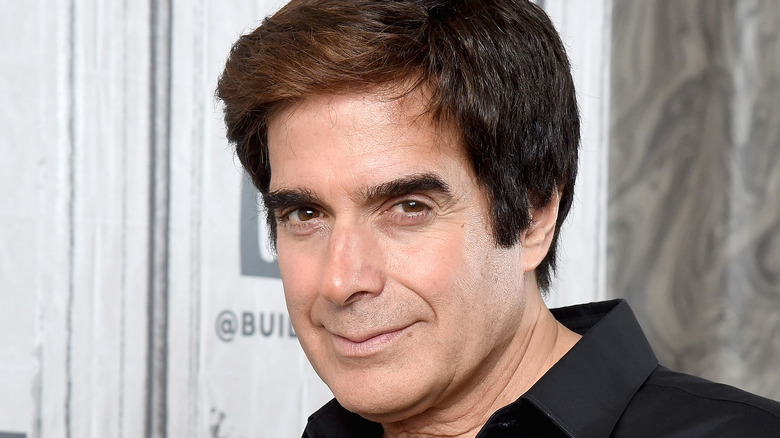

How David Copperfield Made The Statue Of Liberty Disappear