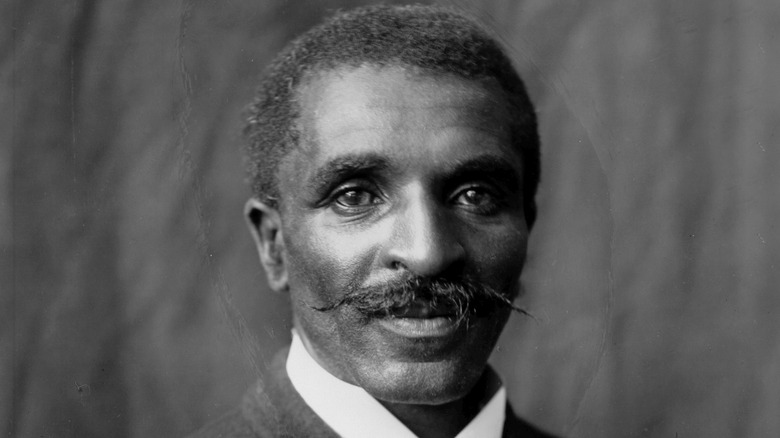

The Truth About George Washington Carver’s School On Wheels

The name of George Washington Carver is synonymous with many scientific and agricultural advancements of the 20th century. At a time when African-Americans were still often seen as inferior to their white counterparts, and even as a former slave, Carver still managed to become one of the most influential scientists of the day. It was the die-hard pursuit of his education that provided him the opportunities to succeed in life.

According to History, he not only graduated from high school in 1880, but went on to become the first African-American to earn both a Bachelor of Science and Master of Agriculture degree in the United States. He then used his position at the Tuskegee Institute, under the direction of Booker T. Washington, to provide a way to bring his knowledge directly to farmers by creating the Jesup Agricultural Wagon.

The Encyclopedia of Alabama reported that Washington had been spending time with farming Black people since about 1881 in his capacity with the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. He spent time with them at their homes, talking, sharing meals, and staying overnight, and he realized that the rural farmers he visited with were in great need of education, but they were too bound to their land to travel to learn. It was a problem. But when Carver was hired on as head of the Tuskegee school of agriculture, things started taking shape.

BRINGING EDUCATION TO THE PEOPLE

The original wagon, named for Morris K. Jesup who financed this project, was a horse-drawn vehicle designed and built by Carver and his students to “take their teaching to the community,” per the National Park Service. They would go on the weekends, bringing materials and necessary tools and give demonstrations to the rural farmers. According to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, Booker T. Washington earned enough political support for the mission in 1897 that the program was dubbed the Tuskegee Agricultural Experiment Station. That distinction upgraded the effort with a government-supplied four-wheeled coach, more tools, seed packets, and “demonstration plants” which were all taken around to teach farmers best practices.

The Encyclopedia of Alabama said that the wagon was incredibly well-stocked to teach farmers about all kinds of aspects of DIY food production: “revolving churn, butter mold, diverse cultivator, planters, a cotton chopper, plows, different kinds of fertilizers, seeds, foodstuffs, a milk tester, and a cream separator, as well as a number of charts and demonstration materials. Recommended breeds of cows and chickens, well-developed ears of corn, stalks of cotton, bundles of oats and seeds, and garden products were included, all based on the locality visited and the season of the year.”

Women were educated by women

While Carver never actually operated the wagon itself, he selected the equipment, drew the charts for farm operations, and chose lecture topics focused on self-sufficient farming, fertilization, and best crops to grow in certain soils (per ACS). This humble-looking truck provided the farmers of rural Alabama access to farming knowledge that they otherwise would not have had.

And it wasn’t just raising animals and crops that was the focus of the moveable school. There was also instruction for women specific to their roles in the house, including how to cook, preserve and can farm-produced foods, how to maintain their homes, and education on health and best sanitary practices was shared, per the Encyclopedia of Alabama. Later, in 1914, there was even an increased focus on educating women when the Smith-Lever Act resulted in more financial support for the traveling wagon school, as the act created a national extension system — or an educational system for those whose livelihoods are based in agriculture. That extension meant that education specific to women’s roles in the household and as caretakers were financially supported and a “woman home demonstration agent” was hired on full time.

In 1918 the Jesup Wagon was replaced with a Ford truck called Knapp Agricultural Truck, after a man named Seaman A. Knapp, who was known as the “father” of the national Cooperative Extension System, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama. In 1920, they brought on Tuskegee graduate and Registered Nurse Uva Mae Hester.

The movable school had far reaching implications, for the good

Overall the effort was a great success. According to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, in the first summer of its educational efforts, an estimated 2,000 people per month benefited from the efforts of George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington’s brainchild. By 1923 the Knapp Agricultural Truck wasn’t enough to keep up with the demand, but it had helped so many for so long that more than 30,000 people chipped in so that the program could buy a new vehicle.

That’s when the little horse-drawn Jesup wagon evolved into its third incarnation, called the Booker T. Washington Agricultural School on Wheels. This upgraded version was now bringing vaccines for livestock, spraying equipment, an early version of a generator, a baby bath and clothes, sewing machines, carpenters tools, medicine cabinets, and even playground equipment, because life shouldn’t be all work. With the federalized extension program getting off the ground, the Tuskegee program that created the moveable school was finally retired in 1944, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

For his efforts, George Washington Carver is not only remembered as using his vast knowledge to revolutionize the agricultural industry. He also helped empower an oppressed group of people to take control of their future.

The Untold Truth Of Spencer

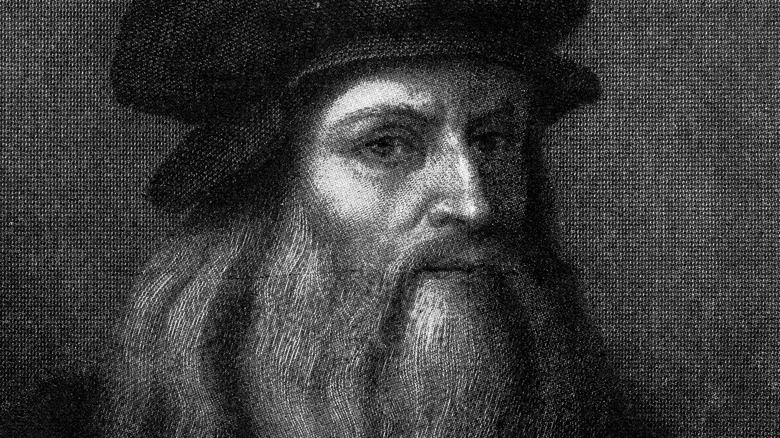

12 Best Leonardo Da Vinci Inventions

What Happens To Your Body When You Are Strangled To Death

This Famous Film Inspired David Bowie's Space Oddity

Why Parents In London Would Set Their Infants In Window Cages

Was The Attica Rebellion Really The Worst Prison Riot In History?

Do We Know What The Sea Peoples' Ships Looked Like?

How Much Al Green Is Actually Worth

The Real Reason Monaco Doesn't Have A King Or Queen

The Secret Deal That Coca-Cola Has With The DEA