The Truth About The Wicked Witch Of The West

We’ve come a long way since 17th-century witch hunters (an actual job) prowled Europe and tortured “witches” for such diabolical crimes as dancing and owning frogs. Witch hunters such as 1620’s Matthew Hopkins, responsible for the Monty Python-spoofed “if it floats, it’s a witch” notion, tortured women decades before the frenzied hysteria of the Salem Witch Trials resulted in 20 deaths and 200 accusations in New England in 1692. And yet, 250 years later, we see the same, tired belief played out in fiction in the form of the Wicked Witch of the West in 1939’s otherwise charming film “The Wizard of Oz,” based on L. Frank Baum’s 1900 novel “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.”

Thankfully, we’ve seen progress. Witches are no longer the kindly local herbalists mistaken for wart-nosed crones in league with Satan; they’re Harry Potter’s friend Hermione Granger. A literal “ice queen” with magic powers isn’t a villain (we’re talking “Frozen” here), she’s the witchy, sometimes misguided, emotionally troubled “frozen” heart of a story. And the Wicked Witch of the West from “The Wizard of Oz,” played on stage in the Broadway musical “Wicked”? She’s a misunderstood outcast, too, the child of a rape victim, forsaken but self-possessed, and “flying high, defying gravity” (clips on YouTube).

The Wicked Witch of the West — Elphaba, as she’s called in the 1995 novel “Wicked,” after which the Broadway musical is based — represents not just a story in and of herself, but the path to tolerance of beliefs and persons once executed for existing.

A cackling, broom-riding symbol of power

“I’ll get you, my pretty, and your little dog, too!” These words, spoken by the cackling, broom-riding commander of the flying monkeys of the enchanted kingdom of Oz, are proven wrong when the Wicked Witch of the West eventually gets melted by mere water (symbol of cleanliness). She shrieks, “What a world, what a world!” while her child assassin, guided by the wise, gentle, far less dark (yikes for sub-textual coding) Glinda the Good Witch, looks on.

Evaluations, insights, and reinterpretations of older stories aren’t mere “woke” nigglings or examples of historical revisionism. Stories help explain the world, revealing the meaning embedded in characters such as the Wicked Witch of the West, who, like all characters, retains deep symbolic value imparted to every viewer. In turn, such meaning and value describes actual centuries of inextricable fears about “witches,” if not millennia-old fears of female power. (If you like, the Journal of Women in Culture and Society can tell you more in “‘Feminist Consciousness'” and ‘Wicked Witches’: Recent Studies on Women in Early Modern Europe.”)

Meanwhile, L. Frank Baum’s original 1900 novel “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” is basically a children’s fairy tale. The Wicked Witch (as she’s called in the book — no “west”), a mere villainous archetype, has no name, as she eventually does in Gregory Maguire’s 1995 novel “Wicked,” upon which the Broadway musical is based. But Dorothy, much like the 1939 movie, is still charged with killing her in order to escape Oz.

L. Frank Baum's fairy tale turned cultural touchstone

Of course, it’s nonsense to think that L. Frank Baum was advocating actual witch hunts à la the 17th century, but he, and his book’s subsequent 1939 film, were building on an old tradition of folklore pertaining to shared fears, as most fairy tales do. He just needed a character for his story — good witch, bad witch (at least he had a good witch). It just so happens that his Wicked Witch is emblematic of the greater shift in attitudes towards “witches” (read: “women who threaten established power conventions”) that bookended the 20th century, from its beginning to its end. First, she was a cruel, featureless creature; then she becomes a sympathetic, multidimensional person.

Not to say that all latter-20th century depictions of the Wicked Witch of the West have been so flattering, despite the overall change in trends. As Evolution of the Wicked Witch of the West reminds us, there’s the 1978 movie “The Wiz,” whereby the Wicked Witch, here named Evillene, is a “sadistic tyrant and probable cannibal” in charge of a modern-day sweat shop. The portrayal gets a pass, though, because of its overall absurdities. The 2013 movie “Oz the Great and Powerful” features the Wicked Witch, Theodora, betrayed by her sister, who gave her a magic apple that “takes away all the good in her heart.” No redemption; she just stays that way.

Each rendition, though, ultimately shares a revelatory similarity: The witch’s power is nothing to be trifled with.

The Truth About The Secret Room In Coughton Court

The History Of Archangels Explained

The Dark Side Of Megachurches

Why The Nile Was So Essential In Ancient Egypt

Why One Criminologist Thinks They've Finally Identified Jack The Ripper

How American Pickers' Danielle Colby Really Feels About Frank Fritz's Exit

The Strange Time In History When Artichokes Took Down The Mafia

What Happened To Rob Gardner From Guns N' Roses?

This Is How Much Ava Gardner Was Worth When She Died

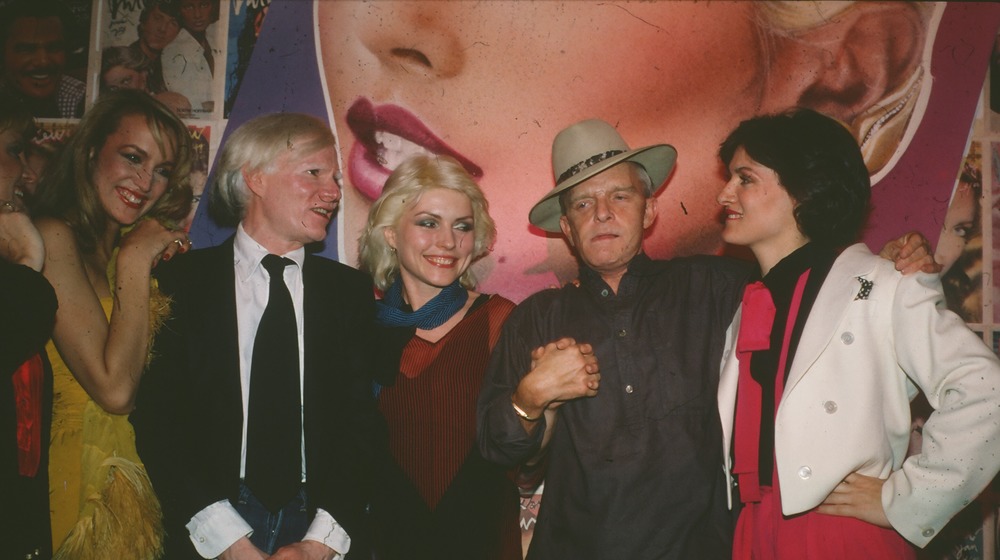

What It Was Like Working At Studio 54