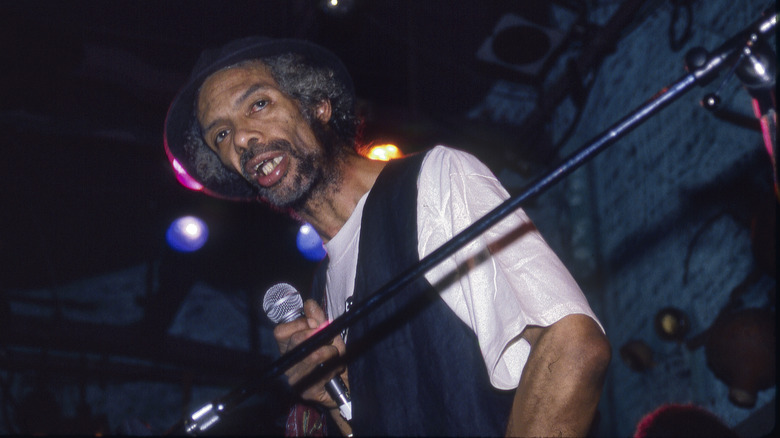

The Untold Truth Of Gil Scott-Heron

Though he preferred to refer to himself as a “bluesologist,” Gil Scott-Heron has been labeled many things. First, he was known as a poet, later, a proto-rapper, and, by the time of his death, the godfather of rap. He has been called both a revolutionary and a countercultural icon, while his manager Clive Davis envisioned Scott-Heron as the “Black Bob Dylan,” according to Newsweek.

But in many ways, Gil Scott-Heron has remained indefinable, a singular personality whose influence has continued to grow in the decade since his death in 2011 at the age of 62. The future star was born in Chicago in 1949, and overcame a turbulent childhood; his parents divorced when Gil was still an infant, and he was sent to live with his maternal grandmother in Jackson, Tennessee when he was just two years old, according to The New Yorker.

Scott-Heron adored his doting grandmother, a relationship he movingly describes on his final album, 2010’s “I’m New Here.” She died when Gil was just 12 years old — he was the one who found her body, according to the same source — and the boy reunited with his mother in New York. Despite his peripatetic upbringing, the young Scott-Heron enrolled in school and excelled, winning a scholarship to the prestigious Fieldstron School in the Bronx, according to Spare Change News. It was during these years that Scott-Heron, through his dedication and natural talent for language (and aided by the influences he would encounter during these years), that he would become what he described as “a Black man dedicated to expression; expression of the joy and pride of Blackness,” per The Guardian.

Young Gil Scott-Heron was incredibly prolific

After impressing at Fieldstron School, Gil Scott-Heron won a place at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, following in the footsteps of one of his literary idols, Langston Hughes, according to Spare Change News. It was here that Scott-Heron would encounter some of his key influences, among them fellow student Brian Jackson, a musician who would go on to become a lifelong collaborator during his recording career, and The Last Poets, an innovative spoken word group whom Scott-Heron met backstage after a performance at the university in 1969, per The New Yorker.

Already well known by friends and teachers for the quality of his writing — he completed his first collection of poetry at the age of just 13, according to Blackpast — Scott-Heron became a prolific activist and chronicler of the Black experience in America in poetry, prose, and spoken word. According to Spare Change News, Scott-Heron suspended his studies after two years and instead wrote two novels, “Vulture” and “The N***** Factory,” the first of which was published in 1970 when he was just 21 years old. The same year, he released his first spoken word album in collaboration with Jackson, “Small Talk at 125th and Lenox,” as well as a poetry collection of the same name, per Poetry Foundation.

“Revolution” is more influential than you might think

“Small Talk at 125th and Lenox” contained an early stripped-back version with just percussion accompaniment of what would become Gil Scott-Heron’s signature song, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” Rerecorded for Scott-Heron’s second album, “Pieces of a Man,” in 1971 with full instrumentation, “Revolution” has become one of the defining statements of 20th-century American poetry, and was added to the National Sound Registry in 2005, according to the Library of Congress.

The spoken-word piece is a seriocomic critique of American consumption, the dominance of white entertainment, and the prevalence of advertising, diversions that pervade American life at a time when the country’s Black population is searching for “a brighter day.” In its deployment of a litany of specific pop culture and contemporary references, it anticipated the sound of a musical genre that would come to dominate the world: hip-hop. “Gil set the template, it’s as simple as that,” claimed Public Enemy’s Chuck D, per The Los Angeles Times. “He set the template for being able to put some sort of rhythm and opinion and expressive thought and a sense of voice and musicality together.”

The song has been sampled countless times, by artists such as Pete Rock & CL Smooth in the 1990s, and, more recently, Travis Scott in 2015, according to WhoSampled, while its lyrical content has been alluded to and repurposed by scores of songwriters, rappers, and poets.

Gil Scott-Heron couldn't heed his own warnings

“A junkie walking through the twilight, I’m on my way home,” sings Gil Scott-Heron on “Home is Where the Hatred Is,” one of the standout tracks on 1971’s “Pieces of a Man.” Just as he critiqued the poverty and political chicanery that blighted the lives of Black Americans in the early 1970s, Scott-Heron was similarly willing to pointedly address the social cost of drugs and addiction — pitfalls that he found himself unable to avoid.

Scott-Heron’s music career progressed steadily throughout the ’70s and early ’80s, when he released close to an album a year, including nine for the enthusiastic Clive Davis’ Arista Records label, according to The New Yorker. Scott-Heron parted with the label in 1985, when the musician’s heavy use of crack cocaine began developing into an addiction, with catastrophic consequences for both his career and his personal life. He would record and release just one more album before the turn of the century, per Rolling Stone: “Spirits,” released in 1994.

In 2001, as news broke of what would be the first of Gil Scott-Heron’s three prison sentences relating to drug offenses, it was reported in The Guardian that his addiction was costing him around $2,000 a week.

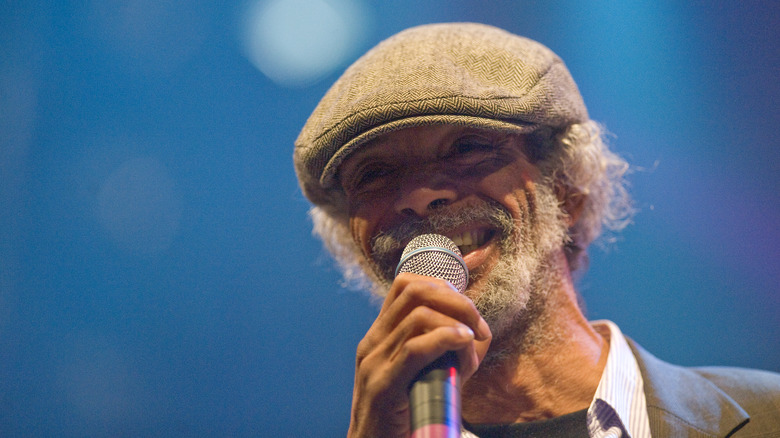

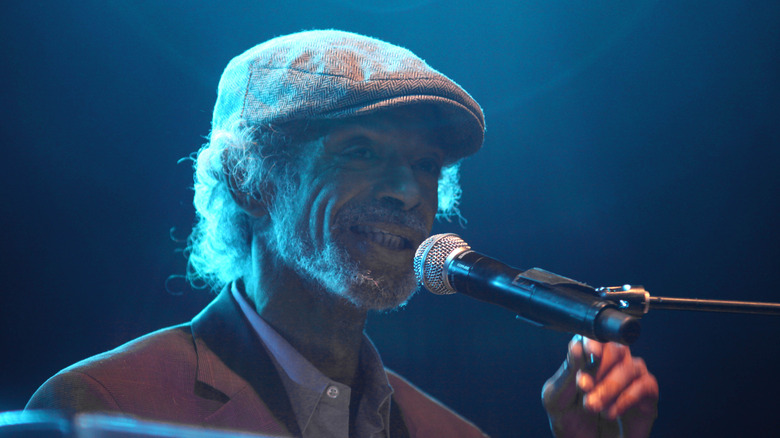

Gil Scott-Heron's had an old-fashioned attitude toward music

Music critics were in awe when in 2009 it was announced, seemingly against all odds, that Gil Scott-Heron — by then considered by most to be a wayward icon — would be releasing a new album, his first in 15 years. The project came about thanks to Richard Russell, founder of the British label XL Records, who decided to visit Scott-Heron while he was imprisoned at Rikers Island and float the idea of a new album, according to The Guardian.

“It’s hard to talk about without sounding outrageously woo-woo,” Russell told The Guardian, “But when I laid eyes on him, the first thing he said was, ‘There you are.'” The two built up a keen understanding, with Scott-Heron and Russell, in something of a retro step for the late 2000s, becoming pen-pals, according to Huck. “I’m New Here” was released in February 2010, to widespread critical acclaim.

The album was remixed in 2011 by British producer Jamie xx — whose work as part of indie band the xx had influenced Russell’s production of the 2010 album — as “We’re New Here,” which set Scott-Heron’s sparse lyricism and soulful vocal performances against a backdrop of techno-influenced electronics, opening up his final work to yet another new audience. Again, Scott-Heron communicated with the British artist through the use of letters by which to discuss production choices, according to Fact Mag.

Gil Scott-Heron's health problems worsen

Gil Scott-Heron died on May 27, 2011, shortly after returning from Europe after a successful live tour in support of “I’m New Here,” the album which turned out to be his swansong. The exact cause of death was not widely reported, however, many obituaries pointed to an interview Gil Scott-Heron gave to New York magazine in 2008, in which he discussed the health problems that had plagued him in recent years. According to the article, Scott-Heron had in recent years been diagnosed as HIV-positive, and had been hospitalized following a bout of pneumonia. He is survived by his children.

In May 2021, it was revealed that Gil Scott-Heron was due to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, receiving an Early Influence Award, according to the institution’s official website. February 2020 saw the release of “We’re New Again” — A Reimagining By Makaya McCraven,” for which the songs of the late artist’s final album were reinvigorated by fresh new jazz instrumentation. Heron’s legacy, it seems, lives on.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit theSubstance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration websiteor contact SAMHSA’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

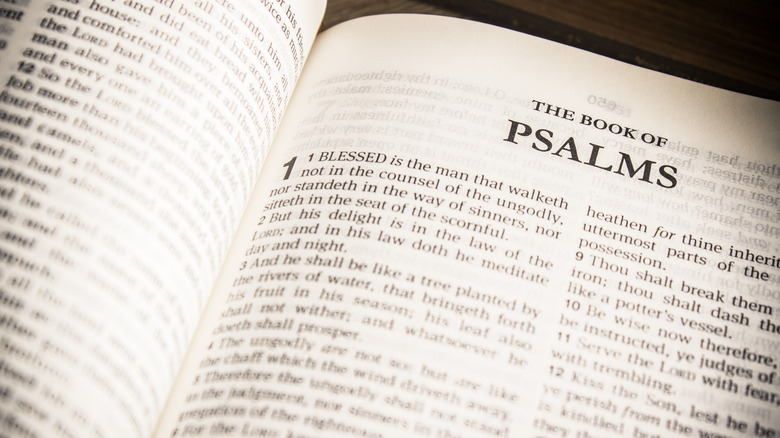

The Untold Truth Of The Book Of Psalms

Is Biggie Smalls Buried Anywhere?

Who Inherited The Notorious B.I.G.'s Money After His Death?

The Mysterious Truth Of The Dutch Schultz Treasure

The Mystery Of The Lost Victorio Peak Treasure

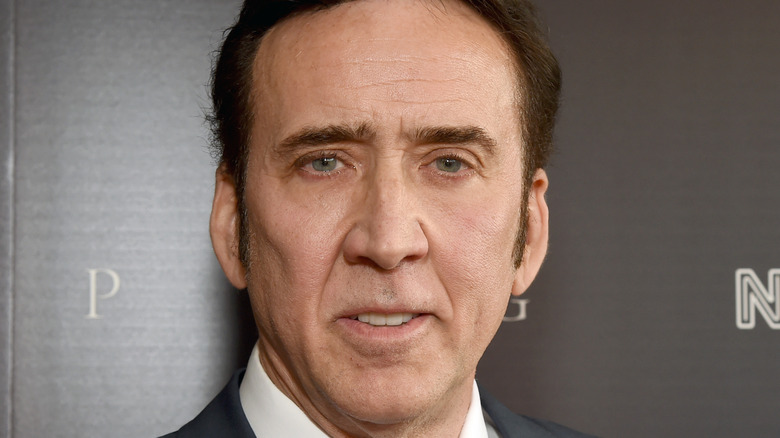

Why Some People Are Convinced Nicolas Cage Is Immortal

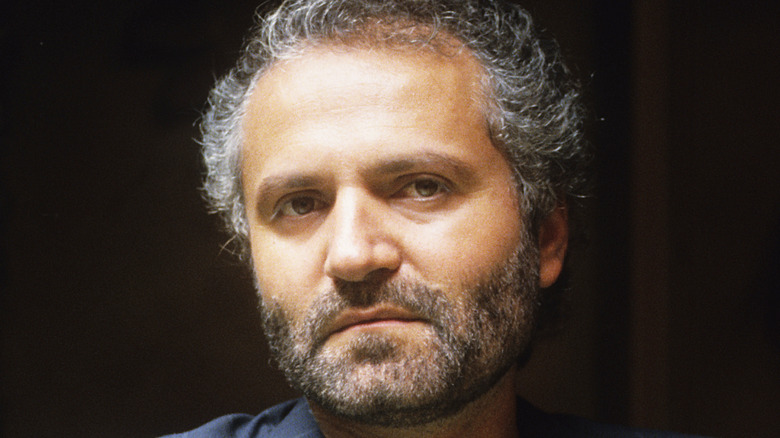

Gianni Versace: The Tragic Real-Life Story

The Wizard Of Oz Scene You Never Got To See Until Now

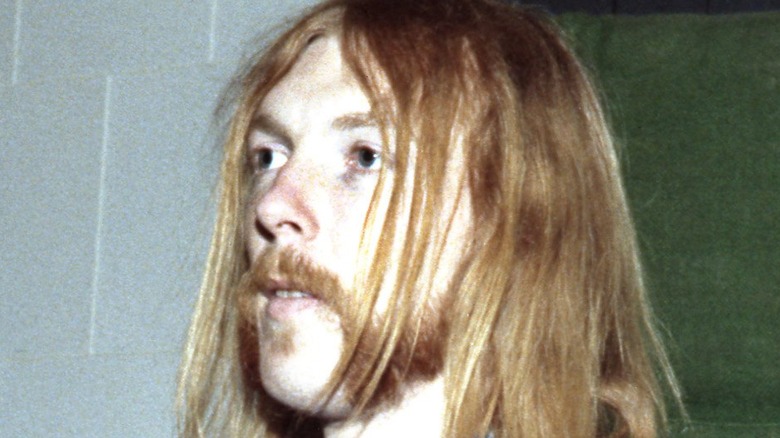

The Eerily Similar Deaths Of Duane Allman And Berry Oakley

Messed Up Things That Happened At The Viper Room