The Untold Truth Of Harajuku Culture

Many aspects of Japan’s popular culture became trends that influenced art, music, and fashion the world over at the turn of the 21st century. Anime and manga became major cultural exports in the late 1980s, and their popularity only grew in the ’90s and into the new millennium. And toward the end of the ’90s, a new culture of street fashion originating in Tokyo’s Harajuku neighborhood captivated attentions all over the globe. Although Japan is now largely over it, the impression that the trend known as Harajuku culture left on the rest of the world endures to this day.

The term “Harajuku style” encompasses a broad range of fashion trends that took inspiration from various sources, but at its core was the combination of western styles with traditional garments like kimonos and details from Japanese culture, such as characters from anime and manga, as well as kawaii, Japan’s culture of cuteness. The story of the precipitous rise and fall of Harajuku street fashion is one of a generation’s desire to express its individualism against a strong current of conformism, and how the power force of convention ultimately won out over the wacky.

The various themes of Harajuku street style

There isn’t one kind of outfit representative of Harajuku fashion. During its heyday in the late ’90s and early 2000s, the neighborhood’s streets crawled with young people sporting a hodgepodge of eye-catching styles. The themes were so varied that Culture Trip was able to compile a list of 10 iconic Harajuku looks. Westerners are probably most familiar with the cosplay theme, in which street fashionistas dress up as their favorite characters from anime, manga, video games, and other visual art. Leaning heavily into the cuteness of kawaii culture, the look known as Kogal and/or Ko-gyaru features the short skirts, blazers, backpacks, and loose-fitting socks of high school uniforms.

Another popular theme with several subcategories is that of the Lolitas. Inspired by the skirts, petticoats, corsets, and other garments of Victorian-era England, the various takes on this style also share the overarching theme of extreme cuteness. The three main Lolita sub-styles include Classic Lolita, Gothic Lolita, and Sweet Lolita, which focuses on being very childlike. There are also Punk Lolitas and a tomboy version known as Kodona.

One of the earliest forms of countercultural fashion trends in Harajuku was Gyaru — a transliteration of the English word “gal.” This term was used for fashion-forward teen girls in the ’70s and went on to represent several styles by the time its popularity reached a peak in the early 2000s. Other styles include Decora, which features vivid colors and tons of accessories, and Ganguro, which is pretty much the fashion equivalent of watching an episode of Jersey Shore.

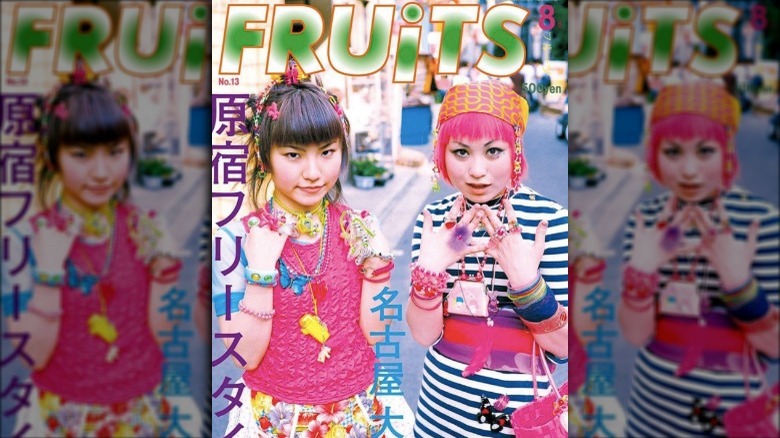

Fruits: the magazine that popularized Harajuku style

So just how did these fashion trends from the streets of a small neighborhood in Tokyo go on to captivate the entire world? According to Dazed, it all started when photographer Shoichi Aoki saw three girls on the street in 1997. Aoki had photographed street fashion in London and Paris in the 1980s, but he’d never seen something quite like what these girls in Harajuku were wearing. “They had brightly colored hair, with a mix of kimono items and western clothes,” Aoki said. “Looking back, we think of these elements as mundane, but at the time they were fresh. These girls made the new style.”

They were also the impetus behind his founding of the street fashion magazine Fruits that same year. Aoki knew that he had stumbled onto something truly unique. “The kids made their own original fashion,” he said, adding that the young people creating Harajuku street fashion were pulling off something that even the avant-garde designers in Japan were unable to do: mix Japanese and western styles in a way that looked good. “The early Fruits years were the first time young people had entered that territory. What’s more, I think they gave a perfect answer. There’s been almost nothing like it since then.”

Fruits ran for two decades, printing its final issue in February 2017. Aoki told Dazed that he was digitizing the 20,000 photos in the magazine’s archives, and he planned on donating them to fashion institutes and other international groups who could use them to preserve the looks for posterity.

Harajuku style wasn't inspired by haute couture

The 1980s were a time of off-the-wall fashion advances in Japan. Designers like Rei Kawakubo, who founded the label Comme des Garçons in 1969, Issey Miyake, and Yohji Yamamoto revolutionized people’s assumptions about what could be considered fashion. Kawakubo, for example, shocked with her cumbersome designs, distressed or defective fabrics, and lots and lots of black.

But while we might want to see links between these innovative designers and Harajuku street fashion, for Aoki, no such inspiration exists. “The Harajuku fashion movement was a counter-movement to the designer boom of Kawakubo, Miyake and Yohji”, he told Dazed. “In the wake of a boom like that, everything that comes out of it starts to look unfashionable. Bright color is a perplexing area in fashion … and a challenge to it.”

So where were the young people of Harajuku taking their cues from if not from the great fashion minds that came before them? Aoki said they most likely found inspiration in one of the most traditionally unfashionable sources possible: their grandparents. He said that while mixing Japanese and western styles had long been a taboo for designers of haute couture, these kids’ grandparents had been doing so for years. The Harajuku fashionistas took their grandparents’ uncool ideas and carefree attitudes and created entirely new looks that pushed Japanese fashion design beyond boundaries the previous Paris-obsessed generation had been afraid to cross.

Harajuku style in western popular culture

It didn’t take long for the rest of the world to get wise to what caught Aoki’s eye on the street that day in 1997. Harajuku fashion and culture took the world by storm and proliferated into even more sub-styles. Soon writers, artists, and musicians all over the world were incorporating elements of Harajuku culture into their work. One notable example was singer Gwen Stefani’s Harajuku girl dancers on her Harajuku Lovers Tour in 2004 and 2005, which as USA Today notes, earned her accusations of cultural appropriation, despite the fact that much of Harajuku fashion itself is unapologetic cultural appropriation.

In their 2003 song “I’m a Cuckoo,” the Scottish indie band Belle and Sebastian sings, “I’d rather be in Tokyo/ I’d rather listen to Thin Lizzy-oh/ Watch the Sunday gang in Harajuku/ There’s something wrong with me, I’m a cuckoo.” But they weren’t the only indie pop rockers from Europe to feel the Harajuku enchantment in the noughties. The video for Peter Bjorn and John’s first single “Nothing to Worry About” features another Harajuku staple. Sporting oversized ducktails and pompadours, the dancing rockabillies of Yoyogi Park aren’t generally included in the lists of Harajuku fashion styles, but as noted by AnOther magazine, they are another group from the district that has used western influences to create their own unique and photogenic sense of identity.

Harajuku style is no longer in fashion in Harajuku

Fashion is by nature a fleeting concept. What’s in doesn’t stay there for long before being replaced by something totally new, or something old enough to be new. So it’s no surprise that the streets of Harajuku aren’t as colorful as they were at the turn of the century. In fact, in 2017, Quartz went so far as to proclaim Harajuku street style “dead.” The bright colors, mismatched styles, and head-turning looks of the neighborhood’s heyday are almost all gone, largely replaced by the normcore looks of fast fashion stores like Uniqlo, Forever 21, Gap, H&M, and other corporate clothing giants.

But while the new generation of Harajuku kids have moved on, the rest of the world largely has not. For many, cute, bubbly Lolitas and Cosplaying teenagers are what come to mind when they think of Japanese youth culture. And in 2019, “Harajuku style” was still the fifth most popular Fashion Style search term on Google. Despite the style’s decline in popularity, the creative ’90s kids sewing their grandmas’ kimonos onto torn-up CBGB T-shirts continue to influence those looking for the next big thing in fashion to this day.

The Surprising Thing That Happened On Ellis Island In The Early 1800s

The Untold Truth Of Victor Hugo's Hunchback Of Notre-Dame

Here's What Really Happened To Mao Zedong's Corpse

The Mythology Of Poseidon Explained

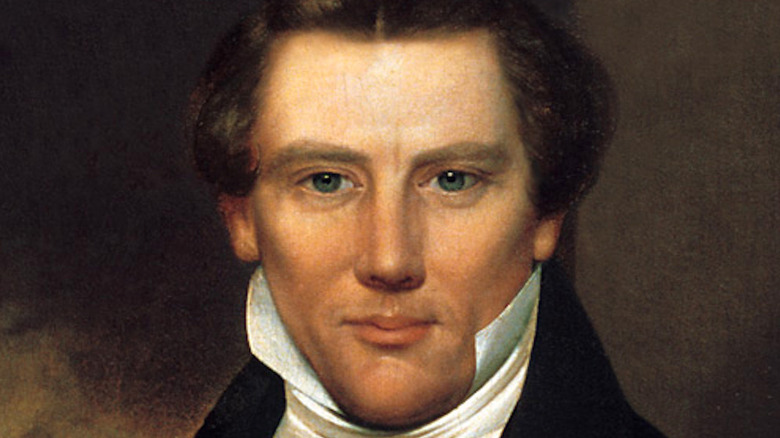

How Many Wives Did Joseph Smith Really Have?

Inside The Soviet Boycott Of The 1984 Olympics

The Truth About Elize And Marcos Matsunaga's Marriage

The Tragic Death Of Barry White

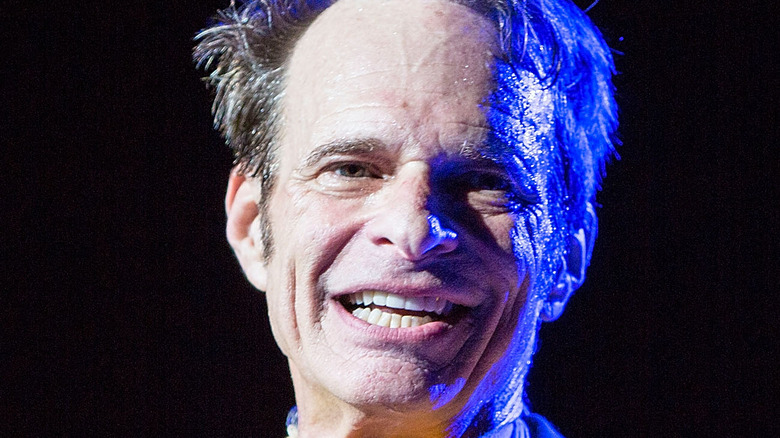

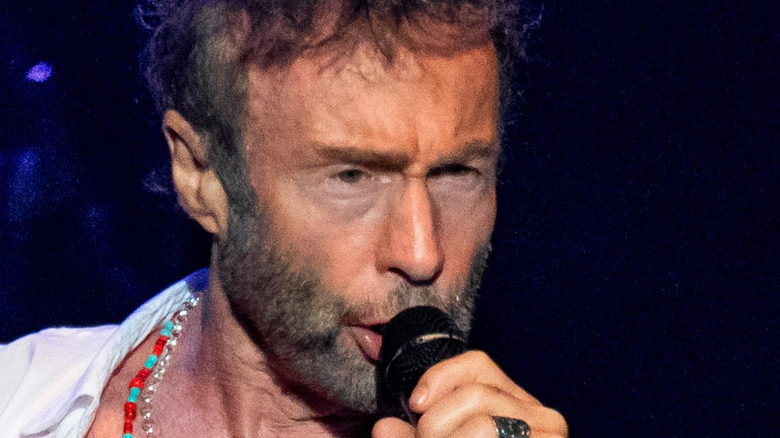

This Is How Much Paul Rodgers Is Actually Worth

Hilarious Animal Videos You Have to Laugh At