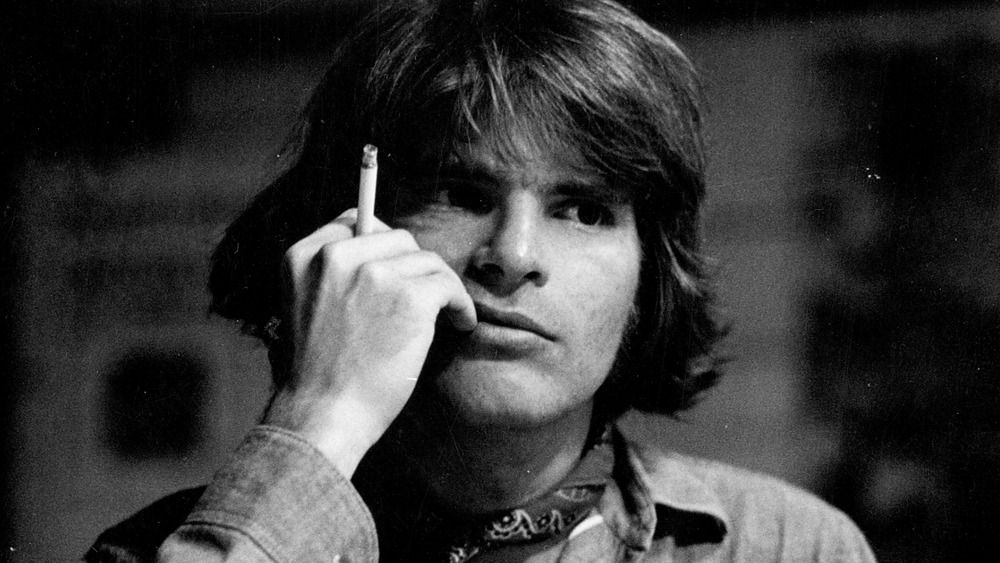

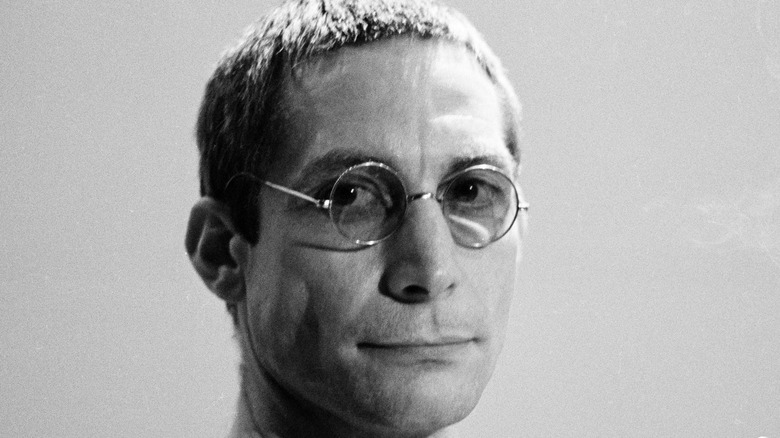

The Untold Truth Of John Fogerty

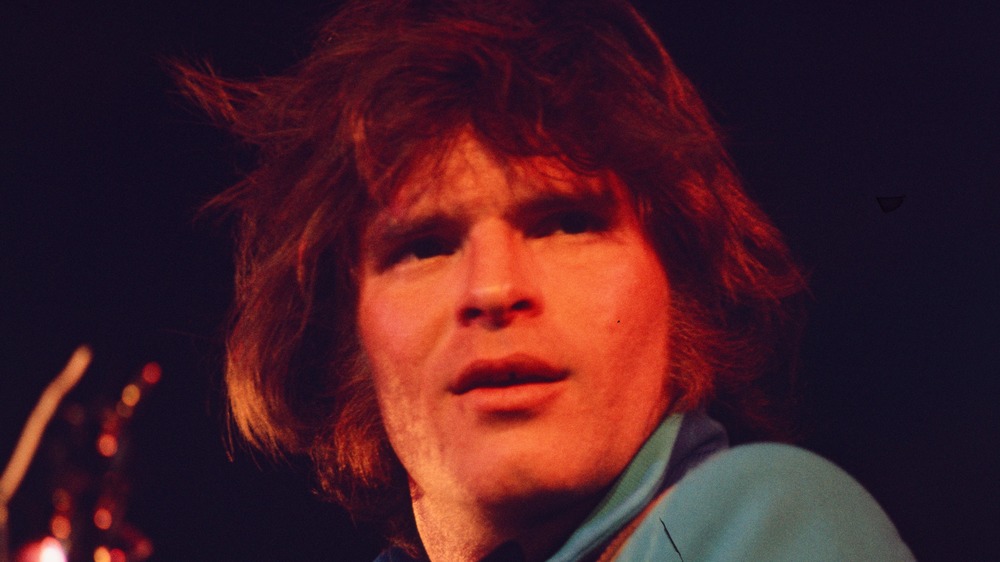

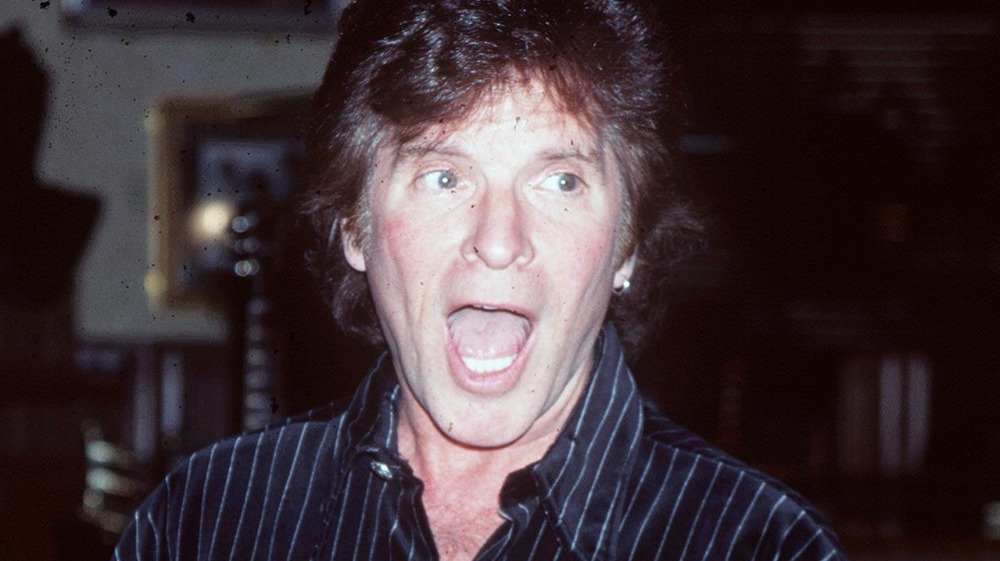

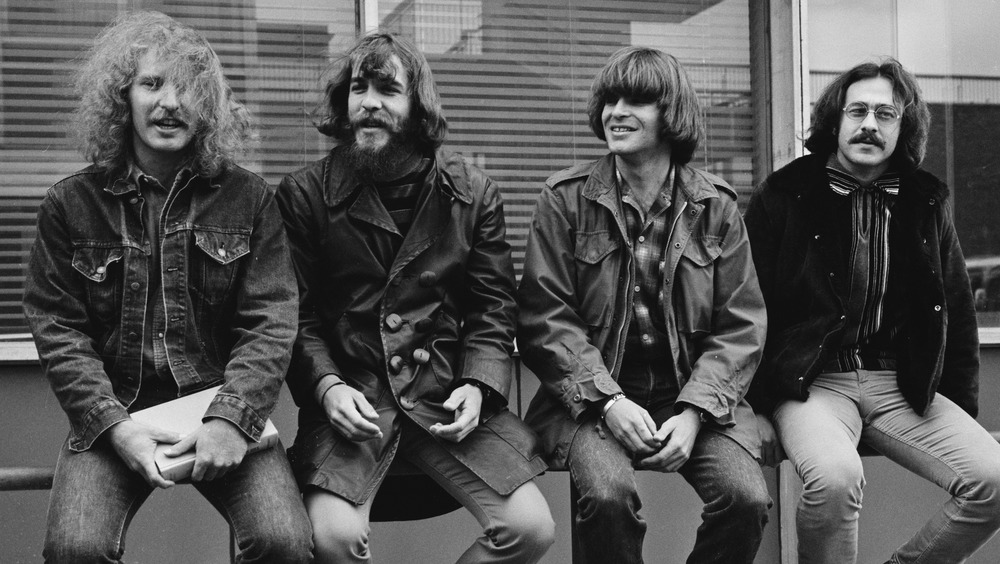

As the lead singer and primary musical force in Creedence Clearwater Revival, John Fogerty helped define one of the most important and exciting eras in rock ‘n’ roll history, becoming the voice of a generation in the process. In the late 60s and early 70s, Creedence scored a string of indelible, pristine, hippie-era rockers and ballads, including “Suzie Q,” “Proud Mary,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Green River,” “Down on the Corner,” “Who’ll Stop the Rain,” and “Have You Ever Seen the Rain.” After CCR’s acrimonious split in 1972, Fogerty embarked on a solo career, taking his self-styled “swamp rock” to the masses alone, continuing to write and record rock radio standards like “Centerfield” and “The Old Man Down the Road.”

Both in CCR and out of it, Fogerty has lived an eventful, dramatic, and remarkable life. Let’s go up around the bend, run through the jungle, and look into the personal and professional history of John Fogerty.

John Fogerty was not born on the bayou

Through his work in Creedence Clearwater Revival and his subsequent solo efforts, John Fogerty has been a proponent and practitioner of “swamp rock,” a style of music that combines 60s-type hard rock with blues, folk, and various forms of folk music native to the Gulf Coast area of the American southeast. Acting like a Louisiana boy is something Fogerty fully embraced, singing in a gritty, raspy voice with a strong twinge of a bayou-area accent on all of his songs, beyond just “Born on the Bayou” and “Jambalaya (On the Bayou).”

While Fogerty obviously loves and appreciates swamp rock and all it represents, he wasn’t born into its geography. The singer-songwriter was born far away from the swamps and the bayou, in Berkeley, Calif., in 1945, as per AllMusic. (However, that city is about 90 miles away from the subject of another Creedence song, “Lodi.”)

John Fogerty was a real-life fortunate son

John Fogerty wrote Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son,” a savage and blistering takedown of young men who used their money, power, and connections to avoid serving in combat in the Vietnam War. Because of its relevant satirical content, and on account of how it was released at the peak of the conflict in 1969, “Fortunate Son” is frequently used in movies set around the Vietnam War. Inspired by his distaste for the lavish, 1968 wedding between Dwight Eisenhower’s grandson and Richard Nixon’s daughter, in contrast to the massive violence and subsequent protests going on, Fogerty composed the song in just 20 minutes, per Financial Times.

Fogerty may have written the tune in such short order because he could pull from his own combat-avoidance history. Right around the same time that he received his draft notice, Fogerty went to an army recruiter and volunteered, hoping to be rewarded with a less dangerous assignment. The future rock legend wound up with a job as a supply clerk in the U.S. Army Reserve, according to the U.S. Army’s Fort Knox News. He went through training at Fort Bragg and was stationed at Fort Knox, serving stateside for about two years in total. “Luckily for me, I didn’t have to go overseas or serve three years in the hard-core Army,” Fogerty told Goldmine, as he was “able to finagle” that spot in the Reserves.

What's a “Creedence Clearwater Revival” anyway?

In the late 60s and early 70s, when rock bands favored short, memorable, and punchy names like Led Zeppelin, the Doors, and the Who, here came a group with a long-winded, vaguely pretentious, mouthful of a name — Creedence Clearwater Revival. Three words, each seemingly carefully chosen — certainly it must have some deeper meaning.

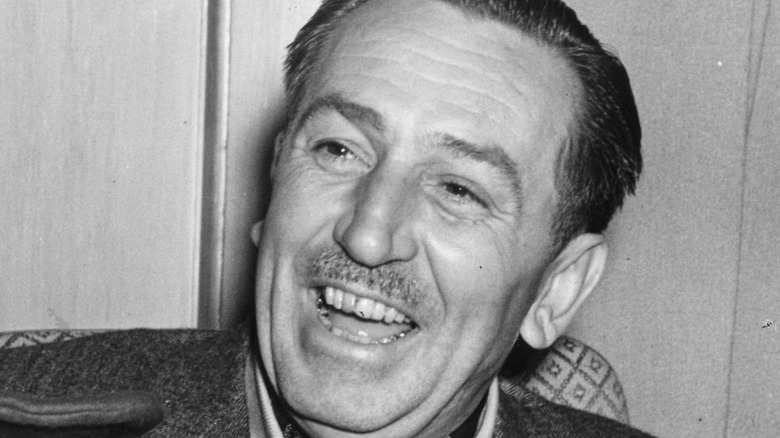

When Saul Zaentz of Fantasy Records signed the up-and-coming band, it was called the Golliwogs. “I hated the name,” Zaentz said in Bad Moon Rising. “It was ridiculous — a stupid name.” The executive struck a deal with the musicians. They’d come up with ten new name possibilities, and he’d come up with another ten, and they’d find one everybody agreed on. According to guitarist Tom Fogerty, some of the suggestions included Muddy Rabbit, Deep Bottle Blue, and Credence Nuball and the Ruby. His bandmates became obsessed with the latter, inspired by the real name of a friend of Fogerty. Then they started surgically building a title, adding an “e” to make Credence into “Creedence,” suggesting a “creed,” or a deeply held belief. Clearwater was taken from an ad for Olympia Beer, produced from “cool, clear water.” Then John Fogerty put those together with “Revival,” because the band felt like they were getting a second wind with their record deal.

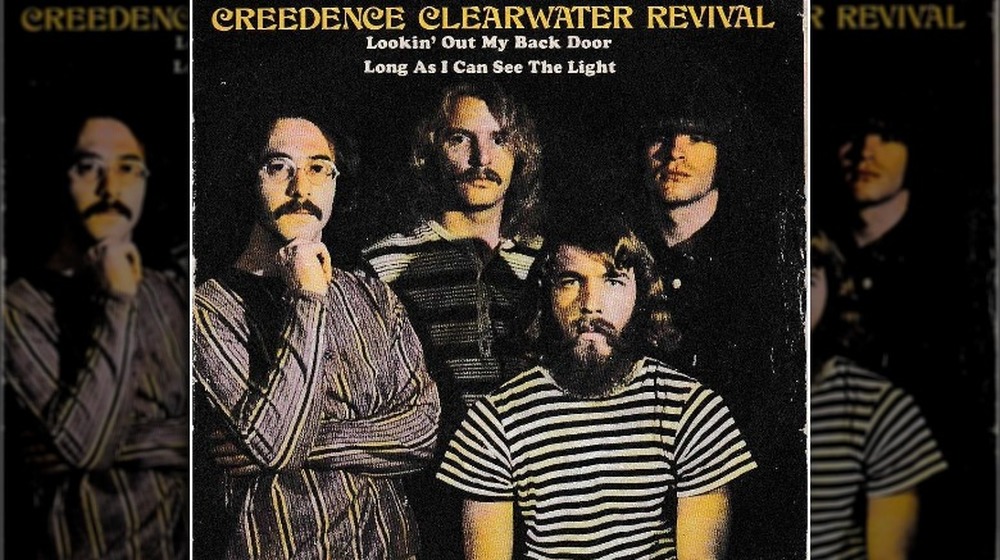

One famous CCR song John Fogerty wrote is just kid stuff

Creedence Clearwater Revival wasn’t just about that hard, fast, and dirty rock n’ roll — the band occasionally released pleasant little ditties that made for great singalongs. Case in point — the joyful and jaunty “Lookin’ Out My Back Door,” a No. 2 hit in 1970. According to CCR drummer Doug Clifford in Bad Moon Rising, John Fogerty “wrote that for his kid,” meaning Fogerty’s son Josh, three years old at the time of composition.

The song describes in great detail a wacky, circus-like parade procession (witnessed by the narrator looking out their back door). Among the sights to behold — a cartwheeling giant, musician elephants, flying spoons, and a magician creating illusions. And to think that Fogerty was inspired by a not-very rock ‘n’ roll source — Dr. Seuss’s 1937 parade-centric children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. “To a youngster, a parade is very exciting, goofy, and bizarre in a kid kind of way,” Fogerty said. “Elephants beating on drums, giraffes, and a monkey playing a xylophone.” He knew his son would enjoy hearing his father’s voice coming out of the radio crooning, “doot doot doo, looking out my back door.”

Nevertheless, the preponderance of weird events and magical creatures led many at the time to think the song celebrated mind-altering drugs. Vice President Spiro Agnew even publicly called out the song for its psychedelic references that weren’t quite there.

“Travelin' Band” got John Fogerty sued

In 1970, Creedence Clearwater Revival took the John Fogerty composition “Travelin’ Band” all the way to No. 2 on the pop chart. It was both new and old at once — a fast and hard-rocking song with howling vocals from Fogerty that spoke to the contemporary rise of heavy metal but also felt like a classic 50s rocker, the kind of frenetic song that Little Richard would have recorded. That evocation was likely no accident — Fogerty was a big fan of the rock ‘n’ roll pioneer. “Little Richard was the greatest rock and roll singer of all time,” he told Rolling Stone. “I was a kid when his records were coming out, so I got to experience them in real time.”

All those great early Little Richard songs — “Tutti Frutti,” “Good Golly, Miss Molly” — were recorded and released by Art Rupe’s Specialty Records, which, according to Forbes, signed the performer to an exploitative and woefully unfair contract, initially paying him $50 for the rights to songs with a half-cent royalty for each copy sold. Specialty controlled “Good Golly, Miss Molly,” and in October 1971, the company felt that CCR’s “Travelin’ Band” was such an egregious rip-off of its Little Richard song that it sued Fogerty for copyright infringement. (The case was later dropped.)

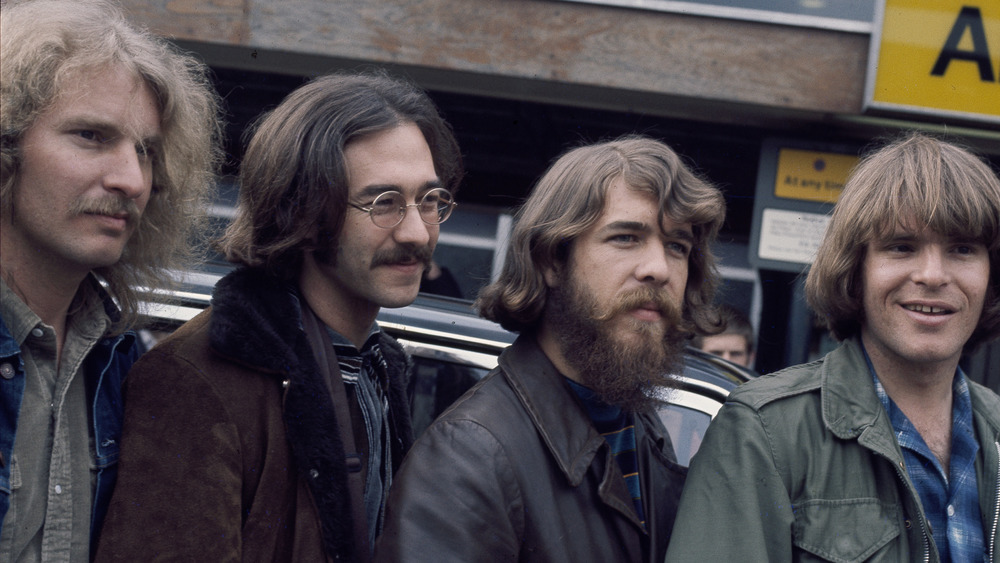

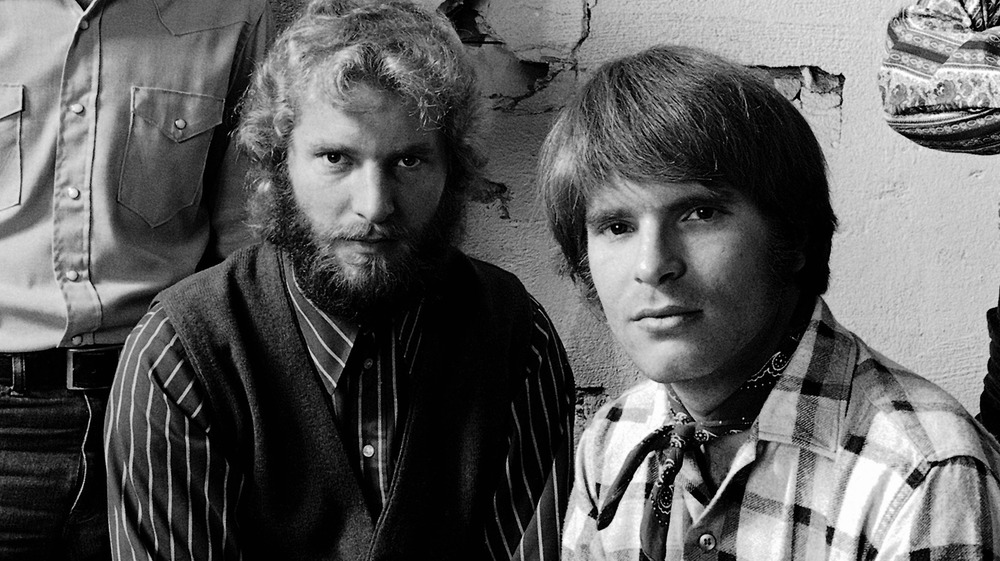

John Fogerty was permanently estranged from his brother, Tom Fogerty

There was another Fogerty in Creedence Clearwater Revival besides John — his older brother, Tom Fogerty. Both had their own Northern California rock bands, per AllMusic, and after his group, Spider Webb and the Insects flopped, he joined John Fogerty in the group that would become CCR. Tom Fogerty could sing and write songs, but John Fogerty quickly emerged as the more dominant frontman and composer. Only one song Tom wrote, “Walk on the Water,” made it onto CCR’s first album. Frustrated by his lack of creative input as CCR rose to the top of the rock world, Tom left Creedence Clearwater Revival in 1971.

That tension was already in place, and disputes over the control of CCR’s music further drove a wedge between brothers. John contributed some work to Tom’s 1974 album, Zephyr National, and saw him occasionally, but they remained distant until the end. According to the Houston Chronicle, Tom died from complications of AIDS in 1990 at age 48, reportedly contracting the disease from a blood transfusion he received after a surgical procedure. Years later, John came to terms with the relationship. “At some point, I made a point to myself of forgiving my brother,” John told Ultimate Classic Rock. “I just felt like I had to do that because he wasn’t around for me to get to work it out with him. I tried but he was so not connected to reality.”

Why John Fogerty disappeared for ten years

After Creedence Clearwater Revival ended in 1972, John Fogerty released a couple of albums, but neither sold well. In 1976, Fogerty put together Hoodoo, but the single, “You Got the Magic,” tanked. Asylum Records opted to shelve the album instead, finding it lackluster. Fogerty had to deal with that personal failure while still dealing with lingering issues over what he felt were unfair deals with Saul Zaentz and Fantasy Records, CCR’s label. Between 1975 and 1985, what should have been prime years for his solo career, Fogerty didn’t make any albums at all. According to The Los Angeles Times, he didn’t start recording again until 1983, then deleted an entire album because he thought it was sub-par. In 1985, Fogerty unleashed Centerfield, where he worked out some demons — the songs “Mr. Greed” and “Zanz Kant Danz” were both about Zaentz, although a slander lawsuit forced him to change the latter to “Vanz Kant Danz.”

The bitterness persisted. According to Billboard, Fogerty didn’t start playing his CCR songs live until 2004. A year later, he signed a new contract with, ironically, Fantasy Records. Zaentz was out of the picture, as the label had sold to Concord Music Group (per The New York Times). In an interview with Ultimate Classic Rock, Fogerty revealed that the full rights to all of his songs will revert to him around the year 2025.

John Fogerty didn't get along with the rest of Creedence Clearwater Revival

Creedence Clearwater Revival’s fifth album, Cosmo’s Factory, is full of CCR chestnuts like “Who’ll Stop the Rain” and “Up Around the Bend.” Its title speaks to simmering band turmoil. According to uDiscoverMusic, the band used to practice in a Berkeley, Calif., warehouse. That atmosphere, along with how John Fogerty made drummer Doug “Cosmo” Clifford relentlessly rehearse, made it feel like a factory.

Fogerty not only determined CCR’s musical direction, but he managed the band, too. “John was brilliant at all the musical things, but he had no experience at managing, particularly at the level we were involved at,” Clifford told Classic Rock. “It was a critical mistake, and ultimately it broke up the band.” After the band split, members took sides. Fogerty, eager to get out his contracts with Fantasy Records, thought his bandmates “betrayed” him (as he told Opie Radio ) because they’d sold their right to vote on band decisions — and thus control of CCR — to label head Saul Zaentz.

While Fogerty and his bandmates remained distant over the years, their lawyers didn’t. According to the Times-Picayune, Clifford and bassist Stu Cook toured in the 90s as Creedence Clearwater Revisited. Fogerty sued in 1996, as he controlled the CCR name. The parties reached an agreement in 2001 wherein Clifford and Cook paid Fogerty a royalty for billing themselves by that Creedence variant. They stopped paying that fee in 2011 when Fogerty disparaged Revisited in interviews — a violation of the legal agreement — which led to even more lawsuits.

John Fogerty was sued for sounding too much like John Fogerty

“Run Through the Jungle” was one of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s biggest hits. The swampy, bluesy song hit No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1970, one of the band’s last successes before splitting up in 1972. The rights to the song weren’t controlled by John Fogerty or CCR as a whole, however, but by Fantasy Records and its owner, Saul Zaentz. He and Fogerty butted heads over the years in a long battle, which took a strange twist after 1985. That year, Fogerty released “The Old Man Down the Road,” which hit the Billboard Top 10, the only time a Fogerty solo song would reach such heights. That might be because it reminded millions of listeners of classic CCR tunes. One man who found it particularly familiar was Zaentz. According to Mental Floss, Zaentz thought “The Old Man Down the Road” bore a striking, undeniable similarity to “Run Through the Jungle.” As he owned the rights to that song, he filed a federal lawsuit against Fogerty for copyright infringement, which put the rock star in the cosmically weird situation of being accused of plagiarizing a song he wrote in another song he wrote.

During the two-week trial in 1988, Fogerty took the stand, wielding his guitar to show judge and jury that while the two songs were similar, it was only because they were representative of his signature musical style. After two hours of deliberation, the jury ruled in Fogerty’s favor.

John Fogerty is in the Baseball Hall of Fame

After a ten-year break from releasing new material, John Fogerty came back in a big way in 1985 with Centerfield, a No. 1-charting album named after the hit single, “Centerfield.” It’s a nostalgic tune about baseball, and it soon became a standard, consistently played over the loudspeakers during games at major and minor league ballparks. (And if not the full song, its introduction — a series of 11 rhythmic hand-claps — is used to get crowds pumped up.)

The song was inspired by stories Fogerty’s father and older brothers told him about legendary baseball players like Joe DiMaggio and Babe Ruth. “When I was a little kid, there were no teams on the West Coast, so the idea of a Major League team was really mythical to me,” northern California native Fogerty told MLB.com. “The players were heroes to me as long as I can remember.” Because DiMaggio, born in San Francisco, played center field, Fogerty came to believe that “the most hallowed place in all of the universe was center field in Yankee Stadium.”

In 2010, Fogerty was recognized for his unique contribution to the national pastime by the gatekeepers of baseball history. The National Baseball Hall of Famehonored “Centerfield” on the occasion of its 25th anniversary. Fogerty played live at the induction ceremony and also donated his custom, bat-shaped guitar to the museum.

Inside the disastrous CCR reunion attempts

Not only did John Fogerty loathe and resent Fantasy Records boss Saul Zaentz, he loathed and resented his former Creedence Clearwater Revival bandmates, Stu Cook and Doug Clifford. That deep, long-standing animosity has precluded Creedence Clearwater Revival from reuniting since its 1972 split. (All four musicians played together again just once, in 1980, at Tom Fogerty’s wedding.)

John Fogerty was given a chance to let bygones be bygones in 1993, when the incoming president, Bill Clinton, asked Creedence to play at the inauguration. Fogerty passed on the high-profile opportunity. “I said, ‘I’m not playing as a band with Creedence. I don’t play with those guys. We will never play as a band again,'” John recalled in his memoir, Fortunate Son (via Rolling Stone).

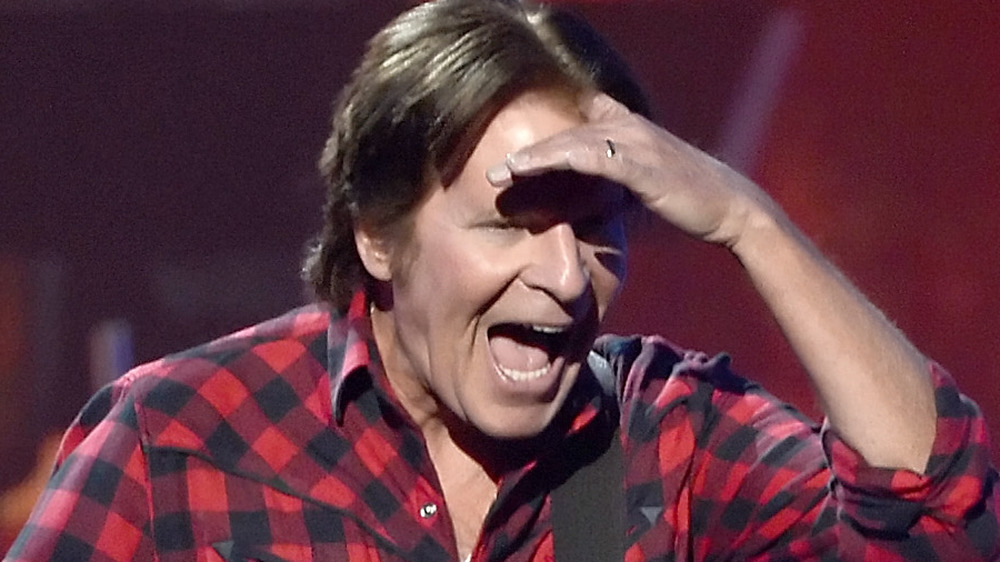

John is a man of his word, CCR still hasn’t played music together, but the surviving original members did all share a stage later in 1993, for speeches, when the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But when it came time for the customary performance for the newly inducted act, Fogerty played with rock legends Bruce Springsteen and Robbie Robertson — he’d prevented Cook and Clifford from taking the stage.

The Crocodile Moment That Had Steve Irwin Fans Seeing Red

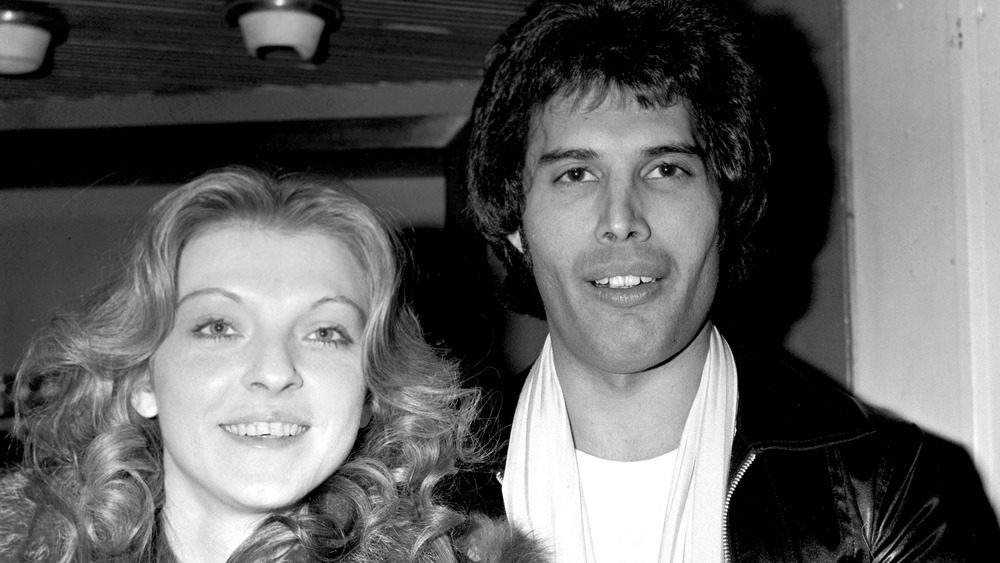

The Important Advice Freddie Mercury Gave Brian May

The Surprising Thing The Rolling Stones' Charlie Watts Did At The Playboy Mansion

Who Was The Better Drummer: Charlie Watts Or Ringo Starr?

What Hollywood Gets Wrong About Demons

The Unsolved Murder Of Hollywood Director William Desmond Taylor

The Untold Truth Of The Bay City Rollers

The Truth About Damian Lillard's Rap Career

This Is What Tommy Chong Did Before The Fame

How Bohemian Rhapsody Got Freddie Mercury And Mary Austin's Relationship Wrong