The Untold Truth Of Nosferatu

Nearly a century after its 1922 premiere, “Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror” remains one of the most compelling and visually arresting adaptations of “Dracula.” Setting the tone for the modern horror film, “Nosferatu” became the template for cinematic terror in the first half of the 20th century, influencing the look and style of the genre’s golden age in the 1930s and ’40s.

As a loose, albeit unauthorized, retelling of “Dracula,” “Nosferatu,” attracted the ire of Florence Stoker, widow of “Dracula” author Bram Stoker, who successfully sued production company Prana Film for violation of copyright. Under the terms of the suit, all prints of the film were to be destroyed. Fortunately for generations of horror fans and film aficionados, “Nosferatu” survived.

From its unsettling atmosphere and stark visuals to Max Schreck’s macabre performance as the ratlike vampire Orlok, “Nosferatu” maintains its power to frighten today. Nevertheless, the story of its production and the artists who crafted this silent classic remains largely unsung. This is the untold truth of “Nosferatu.”

Albin Grau, Nosferatu's occult mastermind

The origins and unmistakable look of “Nosferatu” sprang from the imagination of production designer Albin Grau. As detailed by Fortean Times, Albin Grau was born in 1884 near Leipzig, Germany. A skilled painter, Grau left an apprenticeship as a baker to study at the Leipzig Academy of Art. Unfortunately, the outbreak of the World War I temporarily derailed his ambitions.

After serving as a soldier on the Eastern Front, Grau returned to Germany, where he landed a job as a commercial artist before moving into an industry more in line with his passions. As an artist for Universum Film AG, Germany’s principal film studio of the silent era, Grau created storyboards and concept art for movies.

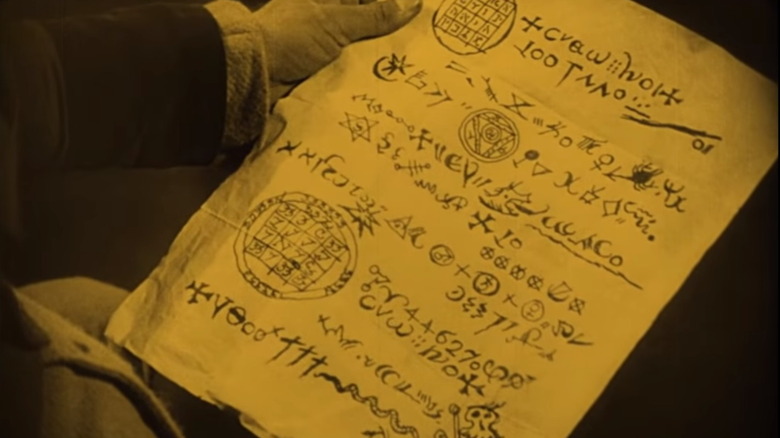

Aside from art, Grau’s guiding passion was the occult. A longtime practitioner of ritual magic, Grau was a member of several German esoteric groups including the Fraternitas Saturni (the Brotherhood of Saturn). Later in life, Grau was briefly an initiate of the Ordo Templi Orientis, led by the notorious Aleister Crowley. In 1921, Grau established Prana-Film with the sole purpose of producing movies with supernatural themes. Prana’s only production was “Nosferatu,” and although the film’s occult elements are subtle, they’re best exemplified in the scenes showing Orlok’s contract, which is covered in astrological, hermetic, and alchemical sigils.

In the 1930s, Grau’s occult practices put him at odds with Germany’s Nazi government and he was imprisoned at Buchenwald. Grau survived and escaped to Switzerland. Following World War II, he moved to Bavaria, where he died in 1971.

Nosferatu: based on a true story?

In “The Haunted Screen,” author Lotte Eisner attempts to explain the zeitgeist that led to films such as “Nosferatu” and “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.” “Mysticism and magic, the dark forces to which Germans have always been more than willing to commit themselves, had flourished in the face of death on the battlefields… And the ghosts which had haunted the German Romantics revived…” the late film scholar wrote. “A new stimulus was thus given to the eternal attraction towards all that is obscure and undetermined, towards the kind of brooding speculative reflection… which culminated in the apocalyptic doctrine of Expressionism.” Consequently, Albin Grau’s vision for “Nosferatu” was as much rooted in the horrors of World War I and life in the post-war Weimar Republic as it was in Bram Stoker’s Victorian novel.

An incident from Grau’s days on the Eastern Front, however, brought him face-to-face with the possible reality of the supernatural, firing his imagination and kindling the spark which would blaze forth as “Nosferatu.” As detailed in Eisner’s “Murnau,” in the winter of 1916, Grau was billeted with an old peasant in Serbia. Captivated, Grau listened to the Serb tell the story of his father who had died without receiving the sacraments and wandered his village as the undead. Grau alleged that the peasant produced an official document detailing the 1884 exhumation of his father. The dead man’s body showed no signs of decay, and his teeth had become abnormally long and sharp, protruding over the lips. Grau claimed that the peasant told him that prayers were said and the supposed vampire was dispatched with a stake through the heart.

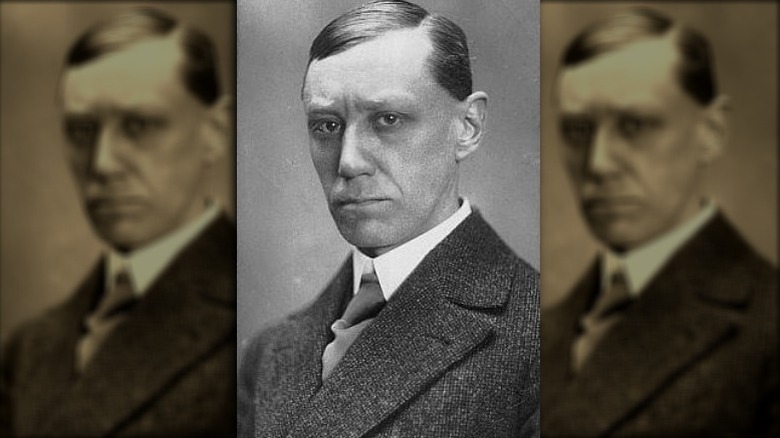

The enigmatic Max Schreck

The bald, emaciated form of “Nosferatu’s” vampire, Graf Orlok, is among the most iconic images in the history of the horror genre. However, the man behind the grotesque makeup remains largely a mystery. Although volumes have been written about Max Schreck’s contemporaries in silent horror cinema such as Lon Chaney and Conrad Veidt, as well as later figures of the genre’s golden age like Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, the life of the man who played cinema’s first real vampire has little in the way of documentation. Even Schreck’s true identity has been called into question with some sources suggesting that he was actually actor Alfred Abel, best known for his roles in Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” and “Doctor Mabuse,” working under an appropriately spooky stage name.

Max Schreck was born in Berlin in 1879. Despite speculation that Schreck — a German word meaning “fear” or “fright” — was a pseudonym, it was indeed the actor’s given surname. The son of a civil servant, Max Schreck trained to be an actor at the Berlin Royal Theater and worked extensively on the stage before entering film. As revealed in a 2008 Reuters interview with biographer Stefan Eickhoff, Schreck was remembered by those who knew him as “a loyal, conscientious loner with an offbeat sense of humor and a talent for playing the grotesque.” He was given to taking long walks through the forest, and one contemporary stated that the actor lived in “a remote and strange world.”

Schreck died in 1936 at the age of 57, having never achieved much notoriety beyond “Nosferatu.”

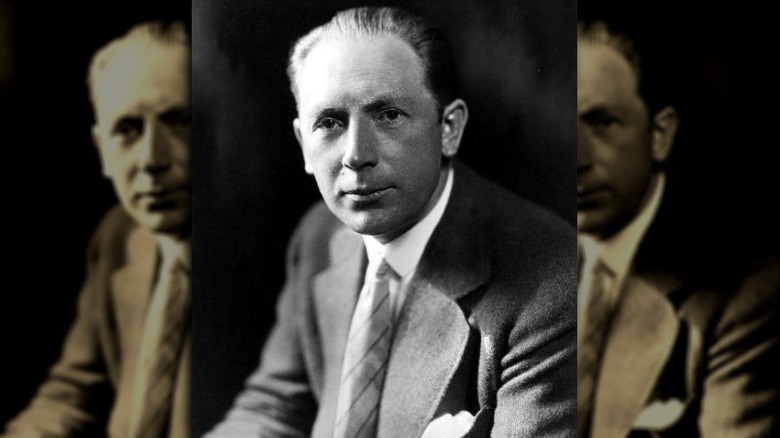

Director F.W. Murnau was a flying ace

One of German cinema’s most celebrated directors, F.W. Murnau was born Friedrich Wilhelm Plumpe on December 28, 1888, in Bielefeld. A precocious reader, Munau developed an affinity for literature and theater as a child. As detailed in “Murnau,” the “Nosferatu” director’s 16-year-old half sister gave him his first taste of the stage, casting him in her attic theater productions when he was just 7.

As a young man, Murnau studied literature and art history in Berlin and Heidelberg, according to Filmportal.de. However, much to his father’s disappointment, Murnau left university to study drama. Dropping his birth name of Plumpe for the stage moniker Murnau — taken from the Bavarian town Murnau am Staffelsee — the young actor sought to distance himself from his parents, who were critical of his artistic ambitions and his life as a gay man. In 1913, he was accepted as a member of Max Reinhardt’s prestigious acting troupe.

However, the outbreak of World War I would temporarily end Murnau’s career in the theater. Drafted into the German infantry, Munau served on the Eastern Front before becoming a combat pilot. During his career as a flyer, Murnau crashed at least seven times, miraculously escaping serious injury. During his last mission, he lost his way in heavy fog and landed in Switzerland, where he was imprisoned for the remainder of the war. While interned, he acted in and directed theatrical productions and assisted in the production of propaganda films for the German embassy in Bern.

Nosferatu star Gustav von Wangenheim fled the Nazis

Like director F.W. Murnau, actor Gustav von Wangenheim, who portrayed Thomas Hutter, “Nosferatu’s” German analog to “Dracula’s” heroic Jonathan Harker, was a protégé of theatrical innovator Max Reinhardt and a veteran of World War I. Born into a family of actors, Von Wangenheim’s career on the stage began early in life. He made his film debut in 1914’s “Passionels Tagebuch” and went on to star in many silent features for such German filmmaking luminaries as Fritz Lang.

Von Wangenheim was also a political firebrand who endeavored to use his art as an actor, writer, and director to spur social change. According to Classic Monsters, von Wangenheim was a dedicated member of the Communist Party of Germany. In 1931, he founded Die Truppe ’31, a Communist theater group that soon ran afoul of the Nazi government and was forced to disband. Von Wangenheim fled Germany for Paris in 1933, and eventually settled in Moscow, where he continued to work in film and theater with other German expatriates until 1935. During World War II, von Wangenheim became a Soviet citizen and wrote scripts for Radio Free Germany as a member of the National Committee for Free Germany. Following the war, he moved to East Germany, where he remained active in the arts until the end of his life. He died in Berlin in 1975

A most unusual casting call

One of the most compelling plot elements of “Nosferatu,” and one that is not present in Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” is the use of its main antagonist as a harbinger of disease and pestilence. When Graf Orlok arrives in Wisborg, he brings with him a horde of plague-infected rats that decimates the population. Ultimately, the vampire’s presence is secondary to the horrors that disease inflicts on the city. With the rise of COVID-19, “Nosferatu’s” themes of disease and quarantine would see renewed relevance a century later.

As detailed in a 2020 feature published by northjersey.com, the producers of “Nosferatu” went to unusual lengths to acquire their cast of rodent extras. On July 31, 1921, Prana-Film ran a newspaper ad that would lead to an unusual casting call: “Wanted: 30–50 living rats.” The ad was apparently successful. In one of the film’s most memorable sequences, Orlok’s coffin is hacked open, unleashing a stampede of vermin.

Following World War II, many critics came to interpret Orlok’s plague of rats as a metaphor for anti-Semitism in the Weimar Republic. Although this reading has merit in retrospect, it was not the intent of the filmmakers. Production designer Albin Grau felt the film was reflective of its era. Produced against the backdrop of Germany’s post-World War I decline and the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which killed 287,000 in Germany alone, “Nosferatu,” in Grau’s words, was reflective of “the monstrous events that had depleted the world like a cosmic vampire, drinking the blood of millions.”

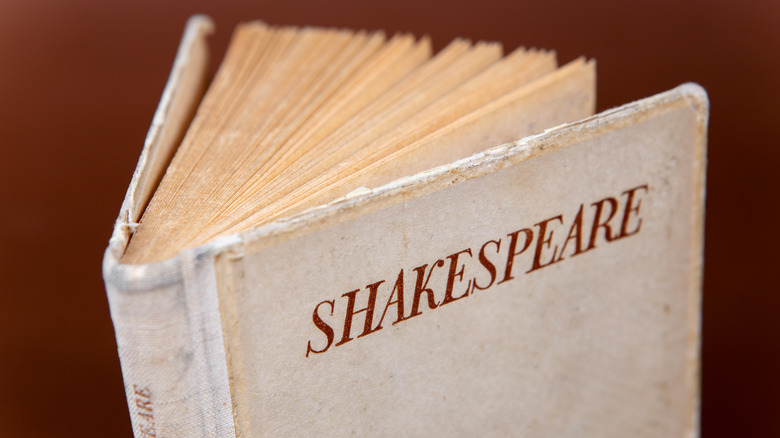

The dubious origins of the word nosferatu

Although “Nosferatu” has long been assumed to be a Romanian word synonymous with “vampire,” the term’s origins present a complicated linguistic mystery. The word entered Western literature with the 1897 publication of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula.” According to horror historian David J. Skal, author of “Something in the Blood: The Untold Story of Bram Stoker, the Man Who Wrote Dracula,” Stoker encountered the word in writer Emily Gerard’s 1885 essay “Transylvanian Superstitions,” which was later included in her book “The Land Beyond the Forests: Facts, Figures and Fancies from Transylvania.” “More decidedly evil is the nosferatu or vampire, in which every Roumanian peasant believes as firmly as he does in heaven or hell,” Gerard wrote. “Every person killed by a nosferatu becomes likewise a vampire after death.”

Despite Gerard’s assertions, “nosferatu” is seemingly unknown in Romanian folklore and all attempts to trace the word dead end with Gerard’s writing. Attempts to find a etymological source for “nosferatu,” also remain inconclusive with the Romanian “necurat” (“unclean”) and “nesuferit” (“insufferable”) as well as the Greek word “nosophoros” (“plague carrier”) offered by various researchers as likely candidates.

In 2011, writer Anthony Hogg discovered an earlier source containing “nosferatu.” Predating “Transylvanian Superstitions” by 20 years, “Das Jahr und seine Tage in Meinung und Brauch der Rumänen Siebenbürgens” (“The Year and its Days in the Opinion and Custom of the Romanians of Transylvania “) by Wilhelm Schmidt contains the mysterious word much as defined by Gerard. However, “nosferatu’s” true origins remain murky.

Nosferatu on location

“Nosferatu” dispenses with the artifice of “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” for an Expressionism that’s more akin to a heightened, yet nightmarish reality. Much of the film’s terrifying atmosphere stems from F.W. Murnau’s use of practical locations. Slovakia was chosen to stand in for “Nosferatu’s” Romanian countryside. But filming in the rough Slovakian terrain of the High Tatras proved challenging. One panoramic shot required porters to carry the camera and film canisters 7,200 feet up a rock wall and hoist the equipment into place with chains.

Some of “Nosferatu’s” most memorable scenes take place at Orlok’s castle, where Hutter first lays eyes on the ancient vampire. Located high above the village of Oravský Podzámok, the 13th century fortress Orava Castle doubles for Orlok’s domain. Today, it stands virtually unchanged and is a popular historical tourist attraction. However, the decaying remains of Orlok’s castle as depicted at the film’s conclusion are actually the ruins of Starý hrad in north-central Slovakia.

The northern German town of Lübeck served as “Nosferatu’s” fictional town of Wisborg. A Unesco World Heritage site, Lübeck’s is home to several “Nosferatu” locations that are still recognizable today, including the Salzspeicher (salt storage house) that serves as Olrok’s German abode, Hutter’s home, and the cobblestone streets through which the coffins of the plague victims are carried.

How Nosferatu miraculously survived

As an unabashed and wholly unauthorized adaptation of “Dracula,” “Nosferatu” famously drew the ire of Bram Stoker’s widow. With “Dracula” her only source of income, Florence Stoker was notoriously protective of her late husband’s copyright. Although Prana-Film’s bankruptcy precluded a monetary settlement, Stoker, who had never seen so much as a single frame of “Nosferatu,” successfully sued to have all prints of the film destroyed. Consequently, the film was very nearly lost.

“Most ‘lost’ films have vanished through neglect,” author David J. Skal writes in “Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen.” “But in the case of ‘Nosferatu’ we have one of the few instances in film history, and perhaps the only one, in which an obliterating capital punishment is sought for a work of cinematic art, strictly on legalistic grounds, by a person with no knowledge of the work’s specific contents or artistic merit.”

Yet, “Nosferatu” survived. In 1925, a livid Florence Stoker discovered that a British film club called the Film Society was planning a private showing of “Nosferatu.” Stoker immediately attempted to seize the film, but the Film Society’s co-founder Ivor Montagu was able to keep her legal agents at bay with evasion and stonewalling. By the time Montagu’s source for the film was discovered, the print had disappeared. Eventually “Nosferatu” turned up in the United States where, through a loophole in copyright law, “Dracula” had always been in the public domain and out of Stoker’s reach.

Nosferatu's Orlok: vampire or something worse?

Although “Nosferatu” is a adaptation of “Dracula,” its antagonist Graf Orlok resembles neither the novel’s aging aristocrat nor the suave and seductive image of Dracula made famous by Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee. Orlok is, first and foremost, an ancient monster. From his first appearance on screen, his true nature is never in doubt.

Allegorical baggage aside, it’s evident that Orlok is much more than he seems. As depicted in the film, Thomas Hutter discovers an old book detailing the origins and habits of supernatural creatures while staying at a Transylvanian inn. In the ancient tome he reads, “From the seed of Belial sprang the Vampyre Nosferatu who liveth and feedeth on human blood.” As detailed by Christianity.com, Belial is a “personification of wickedness and evil.” In the Old Testament, the word refers broadly to lawlessness and rebellion, however, the New Testament specifically identifies Belial as Satan (2 Corinthians 6:15). Given this scriptural context, Orlok is the literal son of the devil.

The bizarre fate of F.W. Murnau

As documented by Turner Classic Movies, F.W. Murnau emigrated to the United States in 1926. Brought to Hollywood at the behest of producer William Fox, Murnau was afforded unprecedented creative control for his first American film, “Sunrise.” An artistic triumph noted for Murnau’s revolutionary camera work, “Sunrise” won the first Academy Award for Best Unique and Artistic Picture (a category that no longer exists). After 1930’s “City Girl,” the director left Fox to make “Tabu” with documentarian Robert Flaherty. Set in Tahiti, “Tabu” was Murnau’s only box office hit after leaving Germany.

F.W. Murnau’s life came to an end on March 11, 1931, when his car, driven by 14-year-old Garcia Stevenson, collided with an electric pole at high speed on California’s winding Pacific Coast Highway. Murnau’s body was returned to Germany, where it was interred at Stahnsdorf Southwestern Cemetery, near Berlin.

In July 2015, graverobbers broke into Murnua’s tomb and removed the director’s skull from his iron coffin. Candle wax left at the scene led to speculation that Murnau’s corpse had been used in an occult ceremony. Murnau’s skull remains missing.

An acclaimed but troubled remake

In 1979, filmmaker Werner Herzog mounted an ambitious and thematically complex remake of “Nosferatu.” Starring Klaus Kiniski as Count Dracula (with “Dracula” in the public domain, Herzog was free to use Stoker’s characters), the film presents the vampire as a lonely outsider who yearns for love and beauty.

Herzog’s “Nosferatu the Vampyre” was a hit with critics, who lauded the film for its visuals and innovative take on the vampire myth. But the film’s production was plagued with accusations of animal cruelty. As detailed by “Albedo One,” 12,000 white laboratory rats imported from Hungary for the production were kept in cramped conditions without food. Consequently, they resorted to cannibalism. Herzog then demanded that the rats be dyed gray in a process that involved submerging them in boiling water. Nearly half of the rats died and the behavioral biologist hired to supervise the animals quit in protest.

The Dark Reason Actors Refuse To Say The Word Macbeth

The Dark History Behind Kleenex Will Surprise You

Did Secretariat Ever Lose A Race?

This City Was Captured For Over A Year During The War Of 1812

The Children Of Bodom Album Alexi Laiho Thought Was The All-Time Best

The Real Reason The Mexican-American War Happened

This Is Stevie Nicks' Biggest Regret

This Is Paul McCartney's Biggest Regret

The Bet Elton John Made With John Lennon

The Truth About Judas Priest And Subliminal Messages