The Untold Truth Of The First Woman Elected To Congress

When discussing history, everyone loves to talk about the “firsts.” You can probably name the first man to walk on the Moon, the first African American president, and — if you’re a history buff — the first explorer to circumnavigate the world. But can you name the first woman elected to the U.S. Congress? If you’re like most people, the answer is probably “no.” But that’s unfortunate, as that woman — Jeannette Pickering Rankin — is a deeply fascinating historical figure.

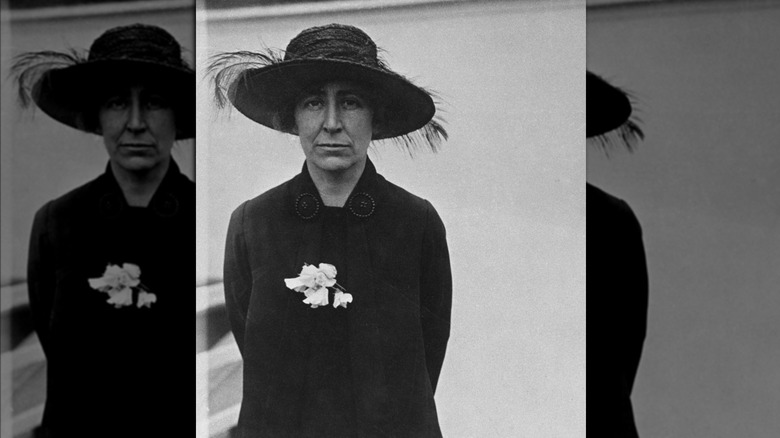

As you’ll see, Jeannette Rankin had a career that spanned decades, and left behind a tremendous legacy. From a young age, Rankin was involved in the women’s suffrage movement — the push to give women the right to vote. When Rankin became the first woman elected to Congress in 1916, she helped introduce legislation that would later become the 19th Amendment, making women’s suffrage a nationwide reality. But, for all her commitment to feminist causes, Rankin’s career was equally devoted to pacifism — and her unwavering pacifism may be what Rankin is best remembered for. In a set of two historic votes spaced decades apart, Rankin stayed committed to pacifism while the country clamored for war, and became deeply unpopular as a result.

The fact that Jeannette Rankin was elected to Congress in 1916 — years before most American women could even vote — is, in itself, astounding. But it is what Rankin chose to do with her power, and how she remained unflinchingly dedicated to her convictions, that makes her a true hero of American history.

Jeannette Rankin grew up on a Montana ranch as the eldest of seven children

Per the U.S. House of Representatives, Jeannette Rankin was born on June 11, 1880, near Missoula in the Montana Territory. (Montana didn’t become a state until 1889.) Rankin was the eldest of seven children — six girls and one boy in all — and spent her childhood on her family’s ranch. Naturally, Rankin was kept very busy; besides having to help care for her younger siblings, she also had to help out with farm chores, History reports. Plus, as a young woman in the 1800s, Rankin was expected to handle other household tasks as well, like cleaning, sewing, and cooking.

As a result, from an early age, Rankin was keenly aware that women had equal labor to men, yet did not have an equal voice. This imbalance is something that Rankin would spend her life trying to fix.

Yet, in spite of her many obligations, Rankin still made time for her education. In 1902, Rankin graduated from Montana State University with a B.S. in Biology. After college, Rankin became interested in the emerging field of social work, which she chose to study at the New York School of Philanthropy in 1908. A couple years later, Rankin moved to Seattle, where she decided to enroll in her third university — the University of Washington — to continue studying the social sciences.

Rankin became involved in the women's suffrage movement while in college

It was at the University of Washington that Jeannette Rankin became actively involved in the women’s suffrage movement. Per the US. House of Representatives, while attending the University of Washington, Rankin decided to become a student volunteer on a women’s suffrage campaign in Washington State. In 1910, those suffragists claimed a big victory: Washington became the fifth state in America to give women the right to vote.

For her role on Washington’s suffrage campaign, Jeannette Rankin was chosen to serve as a field secretary for the National American Woman Suffrage Association. In this position, Rankin received word that a resolution guaranteeing women’s suffrage was about to be introduced to the state legislature in her home state of Montana. However, Rankin discovered that the resolution “was in fact part of an elaborate hoax.” Unfazed, Rankin was able to convince a Montana lawmaker to introduce the resolution anyway.

In February 1911, Rankin became the first woman to ever address the Montana legislature when she argued in favor of the suffrage resolution. Due in part to Rankin’s speech, the resolution went on to receive majority support — but not the two-thirds needed to pass. Even so, Rankin’s activism reawakened the suffrage movement in Montana. As a result of continued campaigning by women, the issue of women’s suffrage was put to a public vote in 1914; Montana’s men voted in favor of giving women the vote, making Montana the 11th state to enfranchise women.

In 1916, Jeannette Rankin became the first woman elected to the United States Congress

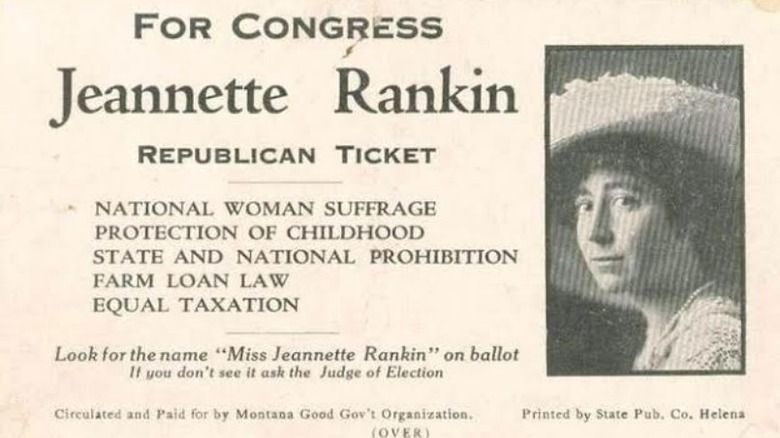

Jeannette Rankin’s role in Montana’s suffrage movement gave her a good deal of public exposure. Rankin decided to capitalize on this, and in July of 1916, she announced her candidacy for one of Montana’s two At-Large House seats, the U.S. House of Representatives reports. If elected, Rankin was going to become the first woman to ever serve in either house of Congress.

Campaigns by women across the West took most of the national attention off of Rankin. However, in her home state, Rankin remained popular. She campaigned as a progressive Republican with a platform that included nationwide women’s suffrage, child welfare legislation, the prohibition of alcohol, and U.S. neutrality in World War I. Rankin followed a grassroots approach, meeting with individual voters and small groups across Montana.

With help from her brother Wellington, who had become a well-established member of Montana’s Republican party, Rankin was able to easily secure the party’s nomination in August’s primary. Then came the general election, which was held on November 7, 1916, per History. The field was crowded with candidates; the top two vote-getters would win the two available House seats. When the results were tallied, Rankin had received the second most votes, granting her Montana’s second open seat — and the title of “first woman elected to U.S. Congress.” “I will not only represent the women of Montana, but also the women of the country, and I have plenty of work cut out for me,” Rankin stated.

In her first week in office, Rankin voted against America entering World War I

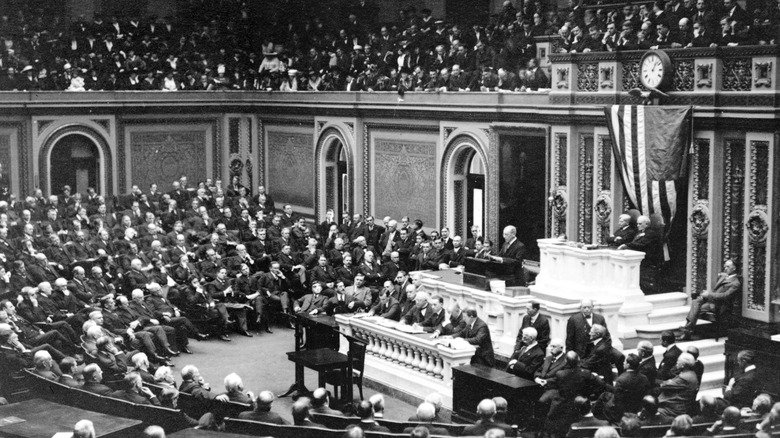

Per History, Jeannette Rankin took her seat in Congress on April 2, 1917. That very same day, President Woodrow Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress “and urged a declaration of war against Germany.” By then, World War I had been raging for nearly three years, and the United States had managed to maintain its neutrality. But, per the U.S. House of Representatives, President Wilson felt that Germany’s submarine warfare and attacks on merchant ships had gone too far.

Rankin found herself in a difficult position; she was a committed pacifist, and had said as much during her campaign, but the American public vastly favored war. Rankin’s colleagues in the suffrage movement urged her not to be too outspoken in her pacifism, worrying that she (and women suffragists in general) might come across as unpatriotic. Similarly, Rankin’s brother Wellington urged her to vote for war.

But when the war resolution was put to a vote on April 6th, Rankin voted “No.” Unsurprisingly, the resolution still passed by a wide margin: 373 to 50. Following the vote, Rankin was widely criticized; one Montana newspaper likened her to “a dupe of the Kaiser” and “a crying schoolgirl,” and even the National American Woman Suffrage Association distanced itself from her. But Rankin did not regret her decision; “I felt the first time the first woman had a chance to say no to war, she should do it,” she would later recall, per American Heritage.

As a congresswoman, Rankin fought for the rights of workers and women

Just five days into her term, Jeannette Rankin had already become a controversial figure in Washington; her pacifism, coupled with her gender, made her a lightning rod of criticism from the media and even from her colleagues. But Rankin had a full two year term ahead of her, and could not let the denigration weigh her down. And on the bright side, per the U.S. House of Representatives, Rankin received letters of support from many of her constituents back home in Montana. So, Rankin remained focused. She dedicated her congressional term to a number of causes — most centrally, towards protecting the rights of women, children, and workers.

In June of 1917 — two months into Rankin’s term — disaster struck at a mine in her home state of Montana, when 168 miners were killed in a fire. The remaining workers went on strike against the company, Anaconda Copper Mining, and Rankin openly supported the striking workers. Rankin took to the House floor to denounce the working conditions at Anaconda and companies like it; Rankin even proposed that the government seize control of Anaconda’s mines, both to improve working conditions there and to supply the war effort with materials. Rankin’s proposal was rejected, but it did gain her more support among working-class voters, whom she continued to fight for throughout her term.

But, as the only woman in the entire country with a voice in Congress, Rankin also used her unique position to continue to advance the women’s suffrage movement.

Jeannette Rankin introduced the legislation that would become the 19th Amendment

During the first year of her term, Jeannette Rankin supported a proposal by California Representative John Edward Raker to establish a House Committee on Women’s Suffrage. That resolution passed, and the Committee was established on September 24, 1917 — with Jeannette Rankin as a Ranking Member, per the U.S. House of Representatives.

According to History, the House Suffrage Committee’s primary goal was to pass a constitutional amendment to guarantee women’s suffrage nationwide. Such an amendment was drafted, and in January of 1918, it was introduced to the House, with Jeannette Rankin personally opening the floor to debate. “How shall we explain … the meaning of democracy if the same Congress that voted for war to make the world safe for democracy refuses to give this small measure of democracy to the women of our country?” Rankin asked.

The proposed amendment narrowly achieved the necessary two-thirds in the House, with a vote of 274 to 136. Per the House of Representatives, women cheered in the House galleries, as it was the first time a suffrage resolution had passed in either house of Congress. Unfortunately, the same resolution died in the Senate. Yet, in 1919 — a year after Rankin had already left Congress — the same suffrage resolution passed through both houses of Congress “with overwhelming margins.” After ratification from three-quarters of the states in 1920, the resolution officially became the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote across America.

Rankin lost her race for the Senate in 1918, but spent two decades lobbying for pacifist causes

Jeannette Rankin’s time in the House was limited. In 1917, per the U.S. House of Representatives, Montana’s At-Large House seats were replaced with congressional districts — and the one Rankin belonged to was overwhelmingly Democratic. Rankin knew she could never win re-election to the House (and suspected that the redistricting may have occurred specifically to keep her out), but Rankin refused to leave that easily. Instead, she announced her candidacy for Montana’s Senate seat in 1918. However — perhaps due to her still-controversial pacifism — Rankin narrowly failed to receive the Republican party nomination. She instead accepted the nomination of an obscure third party, and still received over 20% of the vote in November’s general election.

Rankin was no longer an elected official, but that didn’t stop her from remaining active in politics. Following the end of World War I, Rankin acted on behalf of a number of pacifist groups which sought to maintain lasting peace; she traveled to a peace conference in Switzerland in 1919. Rankin also lobbied Congress to pass social welfare legislation aimed at, among other things, reducing infant mortality.

In 1924, Rankin moved to a farm outside Athens, Georgia, where she lived a simple, low-tech life. Yet Rankin continued her activism, founding the Georgia Peace Society in 1928, per Georgia Women. Living in Georgia allowed Rankin to lobby in Washington, D.C. more effectively than if she had stayed in Montana.

In 1940, Jeannette Rankin was re-elected to Congress

Yet, after two decades of tireless work, Jeannette Rankin found that lobbying was insufficient to truly advance the causes she cared about — particularly pacifist ones. This became especially evident at the end of the 1930s, when it was clear that the United States was likely to be sucked into another world war.

So, per the U.S. House of Representatives, Jeannette Rankin returned home to Montana in 1940 and announced her second candidacy for the House. Rankin’s 1940 campaign followed a similar grassroots strategy to her 1916 campaign — with Rankin giving speeches at 52 of her district’s 56 high schools, per the book “Jeannette Rankin: America’s Conscience.” And, again, Rankin’s campaign was financed and supported by her well-connected brother Wellington — despite the siblings’ increasingly divergent views.

Rankin challenged then-Representative Jacob Thorkelson — an outspoken antisemite — in the Republican primary, and won. Leading up to the general election, Rankin received endorsements from many well-known progressives, including New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. When Election Day came, Jeannette Rankin defeated the Democratic candidate Jerry O’Connell with 54% of the vote. And when Rankin took her seat in 1941, she was no longer the only woman in Congress; she was now one of seven women serving in the House of Representatives, per History.

Rankin was the only congressperson to vote against America entering World War II

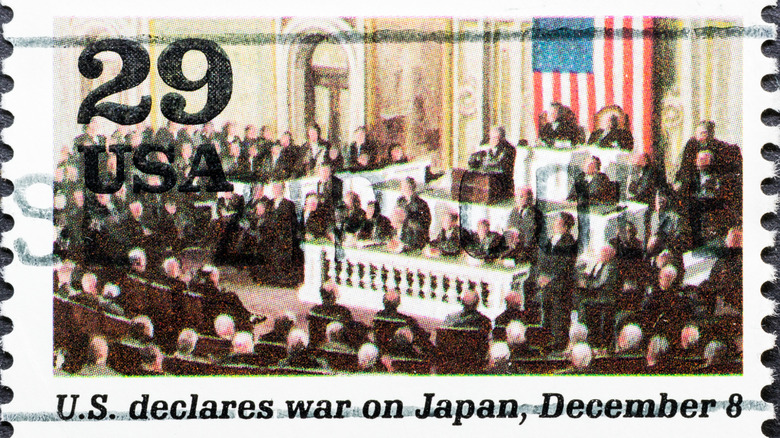

Twenty-two years after her departure, Jeannette Rankin was back in Congress. And, just like in her first term, Rankin again found herself arguing for pacifism in a time when war was far more popular. Throughout 1941, one of the biggest questions facing Congress was whether the United States should enter World War II on behalf of the Allies. But, in the final month of that year, the question was put to rest. On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy conducted a sneak attack on America’s Pearl Harbor naval base, per the National Park Service. When news reached Washington, it was essentially unanimous: America must declare war against Japan and enter World War II.

But it wasn’t completely unanimous. When, the day after the Pearl Harbor attack, Congress considered a resolution declaring war on Japan, one lone voice spoke out against war: Jeannette Rankin. As the floor was opened to debate on the resolution, Rankin repeatedly sought recognition to speak — but the House Speaker declared her out of order, and others called for her to sit down, per the U.S. House of Representatives. When it came time to vote, some of Rankin’s colleagues urged her to vote in favor of the war — or at the very least to abstain — for the sake of national unity. But Rankin refused to abandon her pacifist convictions. When the votes were tallied, the Senate had voted unanimously in favor of war against Japan, while the House had voted 388 to 1.

Jeannette Rankin's opposition to WWII ended her political career

Per the U.S. House of Representatives, on the day she voted against declaring war on Japan, Jeannette Rankin said, “As a woman I can’t go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else.” But, while Rankin’s vote against World War I had made her unpopular, her vote against World War II made her despised. The Associated Press reported that Rankin’s “No” vote was met with “a chorus of hisses and boos” across the House Chamber. When Rankin exited the room following the vote, she was swarmed by fellow politicians and members of the press, and had to take shelter from the mob in a phone booth until the Capitol police could come and evacuate her. In the days that followed, Rankin received furious telegrams and phone calls — some from her constituents back in Montana. One such call came from her own brother Wellington, who told her that “Montana is 110 percent against you.”

While Rankin still had over a year left in her congressional term, her political career was over. Two days later, she chose to vote “present” when Congress declared war on Germany and Italy. In the following months, Rankin found herself shunned by colleagues and the press.

Rankin tried to make the most of her remaining time in office, focusing primarily on addressing wartime fraud and protecting free speech. But, when her term expired, Rankin knew she had no future left in politics; she chose not to run for re-election.

Rankin remained a passionate pacifist, leading demonstrations against the Vietnam War

After leaving Congress, Jeannette Rankin split her time between her homes in Georgia and Montana. Per the U.S. House of Representatives, Rankin also spent her retirement from politics traveling — including to India, where she studied the pacifist teachings of Mahatma Gandhi.

In the United States, Rankin was a role model for generations of younger pacifists. In the 1960s, Rankin became openly critical of the Vietnam War — and, despite being in her 80s at the time, Rankin decided to mobilize a pacifist movement against it. Per American Heritage, in 1968, Rankin led 5,000 black-clad women — the Jeannette Rankin Peace Brigade — on an anti-Vietnam War march in Washington, D.C. It was one of the biggest marches by women that the country had ever seen. In 1972, per the House of Representatives, the National Organization for Women named Rankin the “World’s outstanding living feminist.”

That same year, at the age of 92, Jeannette Rankin considered running for Congress for a third time to further advance her anti-Vietnam War message. However, heart and throat problems prevented Rankin from making a final congressional run a reality. Later in life, Rankin was asked if she regretted the 1941 anti-war vote that ended her career in politics. “Never,” she replied, per biographer Mary O’Brien. “If you’re against war, you’re against war regardless of what happens. It’s a wrong method of trying to settle a dispute.”

Jeannette Rankin died in 1973 at the age of 92

Per the New York Times, Jeannette Rankin died on March 18, 1973, at the age of 92. Rankin had lived an incredibly busy life — from early fights to women’s suffrage, to two congressional terms, to tireless lobbying and activism. Rankin never married, but did maintain “a lifelong, intimate relationship” with the journalist Katherine Anthony, per Politico. As a result, historians have debated Rankin’s sexual orientation — but generally agree that she was too busy for long-term romance.

When Rankin died, she gave away her estate to help “mature, unemployed women workers.” Today, the Jeannette Rankin Women’s Scholarship Fund that was established through her original donation reports having awarded $3 million dollars in scholarships to over 1,000 women.

To this day, Jeannette Rankin remains the only woman elected to Congress from the state of Montana, per History. But, even so, Rankin paved the way for hundreds of women to enter U.S. politics in the 20th and 21st centuries. Jeannette Rankin left behind an impressive legacy of pacifism and feminism over her decades-long career. Per the Bill of Rights Institute, in 1972, Rankin stated, “If I am remembered for no other act, I want to be remembered as the only woman who ever voted to give women the right to vote.”

How Ronald Reagan Saved The Lives Of 77 People

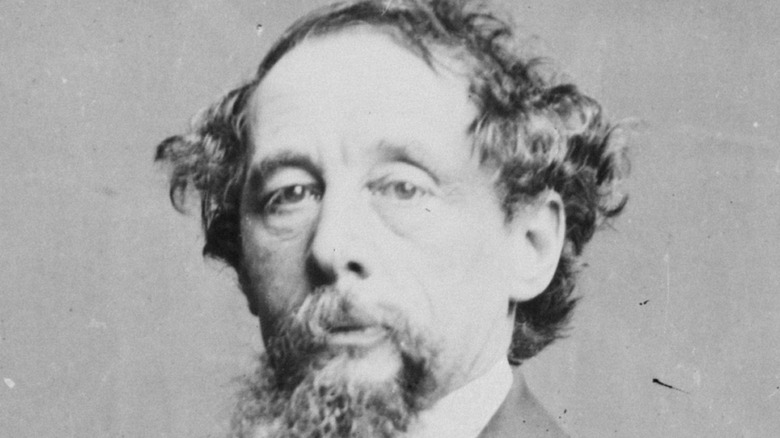

The Tragic Deaths Of Charles Dickens' Siblings

Canada's Most Dangerous Cities

The Untold Truth Of Sharia Law

The Tragic Story Of The Huascaran Avalanche In Peru

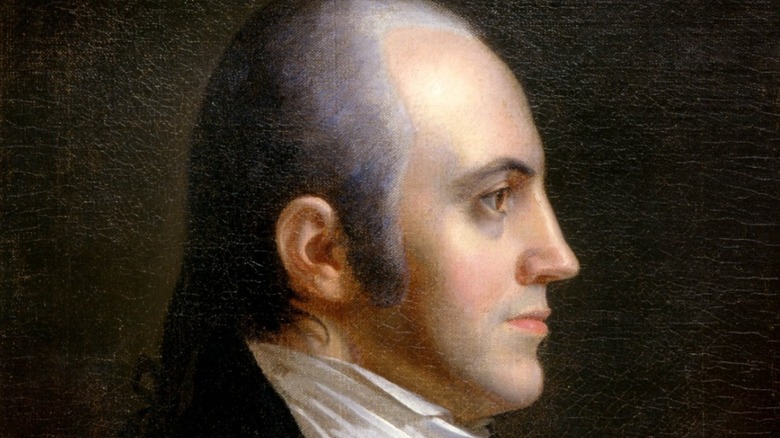

The Tragic Death Of Aaron Burr's First Wife

What Dragons Look Like Around The World

What You Didn't Know About Joseph Bell And Florence Nightingale's Friendship

Musicians Who Were Ahead Of Their Time

Why Pope Francis Thinks People Should Embrace Tattoos