Things Gladiator Got Right About History

Ridley Scott’s “Gladiator,” released in 2000, remains one of the most epic historical dramas of the 21st century (via Esquire). From its sweeping cinematography and soul-stirring musical score by Hans Zimmer to its deeply moving storyline and romance that endures beyond death, it represents a modern classic. Elaborate sets, sumptuous costumes, and flawless action scenes present the Roman Empire at its height, with clear shadows of the fall to come. What’s more, the movie features incredible performances by Russell Crowe as Maximus Decimus Meridus and Joaquin Phoenix as the villainous Emperor Commodus.

According to IMDB, “Gladiator” cost roughly $103,000,000 to produce and grossed $34,819,017 in its opening weekend in the U.S. and Canada alone. And when all was said and done, the movie’s worldwide gross came in at a whopping $465,380,802. But impressive statistics aside, there are many unanswered questions regarding the historical basis for “Gladiator.”

For example, did a Roman General named Maximus ever exist? And did he end up in the gladiatorial ring due to a stroke of cruel fate? As for Commodus, was he really as bad as the film makes him out to be? Here’s what you need to know about the true history that inspired “Gladiator.”

The struggle was real in Germania

It’s hard to beat the opening scenes of “Gladiator” (via Screen Rant). A headless rider breeches the tension, sent into a Roman camp by opposing Germanic tribesmen. They punctuate the intimidating message by throwing the rider’s head in next, complete with ancient Germanic insult-hurling. Of course, the ancient Romans, never ones to shrink from a fight, remain stalwart.

Without a second thought, Field General Maximus Decimus Meridus orders a hailstorm (or, rather, firestorm) of flaming arrows and other incendiaries. Then, he sends in his troops to crush the opposition, all while Emperor Marcus Aurelius watches breathlessly from a safe distance. Few scenes in cinematic history prove as bloodthirsty and fantastic. From Maximus’ epic “what we do in life echoes in eternity” speech to the hardened Roman legion to the eerie forest setting. But did this battle actually take place? According to the Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, it sure did — at Vindobona, the modern-day site of Vienna.

The catapults launching flaming projectiles and the bolt throwers prove suspect, however. Sure, these weapons existed for stationary defense. But using them as siege weapons on a portion of the forested frontier? Not so much. But the battle did pit Roman soldiers against the indigenous people of Germania. And Ridley Scott got much more or less correct about the end of Emperor Marcus Aurelius’ Twelve Year Campaign, which began in 167 or 168 A.D. (via Britannica). The Battle of Vindobona marked the decisive win the Romans needed to clinch this conflict.

The (not-real) historically accurate hero

Maximus Decimus Meridius was a fictional vessel thought up by Hollywood mavens to effectively tell the story they envisioned. Nevertheless, his character is firmly grounded in actual history, from his bearing and demeanor to his dreams of becoming a farmer once his military service ends.

According to ThoughtCo., the model of a Roman man dates back to Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus. He lived in the 5th century B.C., and was a celebrated statesman, military man, and … you guessed it … farmer. Of these three titles, farmer best suited him. Kind of like Maximus, from the opening scene of the movie to the last. That said, Cincinnatus sacrificed all when the Roman Republic needed his help (despite the fact a lengthy absence on his part meant the ruin of his farm and food insecurity of his family).

Fortunately, he didn’t meet the same nasty fate as Maximus. Instead, Cincinnatus became a prominent character in Roman literature as a “model of Roman virtue.” Besides the example that Cincinnatus set, he also displayed two Roman virtues in spades: fides and pietas. According to The Great Courses Daily, fides translates as “faithfulness.” But it refers to something much broader, “sticking to a task and seeing it through to the bitter end.” As for pietas? In a word, it means “piety.” Again, there’s a deeper implied meaning, “doing the right thing.” These two traits define Maximus’ character throughout “Gladiator.”

Infighting between the Praetorian Guard and the Legion

Remember when Maximus Decimus Meridius kills his would-be executioners, referring to one derisively as “Praetorian”? There’s legit historical context for this event. Serious tension existed between the Praetorian Guard and the Legion.

The Praetorian Guard had a less-than-stellar reputation as the personal guard of the Roman Emperor (per World History). According to the History of Yesterday, they assassinated 13 of the emperors in their care and “even auctioned the throne to the highest bidder.” The infamy associated with the terror, treachery, and greed they caused soon preceded them. Surprisingly, things started out okay. Caesar Augustus assembled the unit as his personal bodyguard in 27 B.C., and he enjoyed a long life. Three centuries later, however, deep-seated corruption shrouded the military unit. Not only did they murder the men entrusted to their care (isn’t there a circle of hell for this?), but they held some emperors hostage, wielding political power through the sword.

The Guard ballooned from 4,500 soldiers to 15,000 by late imperial times, and they received triple the pay of legionaries like Maximus and his men. Instead of serving 20 years, the Praetorians got off at just 16. And as you can imagine, each new emperor had to pay the Guard steep bribes to stay alive. Things finally came to a head under the reign of Emperor Constantine I, who managed to disband the unit without getting skewered in the process.

Legions and their generals proved thick as thieves

There’s nothing like suffering through battles, blood loss, and uncomfortable deployment living conditions together. These realities of life on the warpath cemented a deep and abiding sense of loyalty for the soldiers of Roman legions and their generals, per PBS. “While soldiers were loyal to their emperor, this loyalty was nothing compared to the loyalty felt by many legions to their commanders.” So, the blind faith that Maximus Decimus Meridus’ men have in him proves spot-on.

Not only did hardship bind these troops and their leaders together, but they had an unprecedented focus on discipline. No army on the planet compared with the training of Rome’s legionaries. Nonetheless, danger still abounded when invading enemy territory.

Rome’s frontiers proved especially challenging for the soldiers posted there. Why? Because they never had sufficient supplies, got no breaks from the rigamarole of being a soldier, and faced constant hostility from native peoples. There weren’t any local bars to unwind in after hours, and getting lost on a bathroom break in the forest could mean a violent death. Despite all the aforementioned discipline and training, death constantly loomed. Nothing better illustrates this than the unexplained disappearance of 5,000 soldiers of the Ninth Legion along the English-Scottish border during the Emperor Hadrian’s reign. Their final fate remains a mystery to this day, according to the BBC.

Marcus Aurelius really was a cool old dude

Marcus Aurelius was far from your average bloodthirsty, power-hungry, and ruthless emperor (via Britannica). He insisted his adoptive brother Lucius Verus co-rule with him, an unprecedented move in Roman history. Verus had a meager fanbase and represented a “sitting duck” easily scratched out by a man less-reputable than Marcus Aurelius.

But Aurelius’ adoptive father, Emperor Antoninus Pius, had requested the unique arrangement. Aurelius proved a man of his word. In an age when people often had little choice over their career paths, Aurelius proved no different. He longed to be a bookworm and philosopher rather than a great military leader and statesman. Towards the end of his life, he wrote in a journal since published as “Meditations.” The work attempts to reconcile his life and daily activities with his stoic philosophy and desire to study, per History.

The movie “Gladiator” depicts Marcus Aurelius as a logical, justice-minded, and competent individual who spent a lot of time thinking. In this sense, it does a decent job of describing his actual character and interests. What’s more, many scholars believe Aurelius died on the frontier at Vindobona as the movie depicts. However, overwork and stress got him in the end rather than Commodus’ murderous grip. That said, you can’t blame Ridley Scott for wanting to spice things up a bit. After all, watching a workaholic’s dying breaths would have done little to demonstrate Commodus’ irrevocably flawed character.

Commodus was a truly nasty guy

The movie “Gladiator” depicts Commodus as a true uber-villain, and this is no exaggeration. If anything, Hollywood handled him with kid gloves. The real-life ruler gave Caligula and Nero runs for their money. No wonder he enjoyed a short career as Roman emperor, murdered by a wrestler while taking a bath at the ripe old age of 31 Britannica explains that “His brutal misrule precipitated civil strife that ended 84 years of stability and prosperity within the empire.” That’s quite a legacy.

All That’s Interesting sums Commodus up as “a paranoid megalomaniac who played gladiator and thought he was a god.” Declaring himself the Greek god Herakles incarnate, Commodus commissioned a marble bust in the accouterments of the Hellenic hero, including Hesperides’ golden apples, a club, and a lion skin headdress. A standard-bearer for Roman portraiture by today’s standards (per Musei Capitolini), at least Commodus knew how to choose a sculptor!

As a tween, he had a servant thrown to his death in a furnace for providing lukewarm bathwater (via the Los Angeles Times). As an emperor, he kept a harem of more than 600 boys and women. He shirked his leadership duties, leaving them to Marcia, his mistress, and a handful of other self-serving favorites. And he focused on his gladiatorial career, charging the empire the ridiculous sum of 25,000 silver pieces each time he fought. History tells us he made 735 appearances. Do the math on that!

Rome did have a Senate

The movie “Gladiator” depicts Roman senators opposing Commodus. This longstanding institution endured both the Republic and the Empire. But the film also couches them in an anachronistic democratic context that didn’t exist. Although the Roman Republic boasted a democratic constitution, “in practice [it was] a fundamentally undemocratic society, dominated by a select caste of wealthy aristocrats” (via Inquiries Journal). What’s more, by the time of Commodus, centuries cemented the transition to an empire.

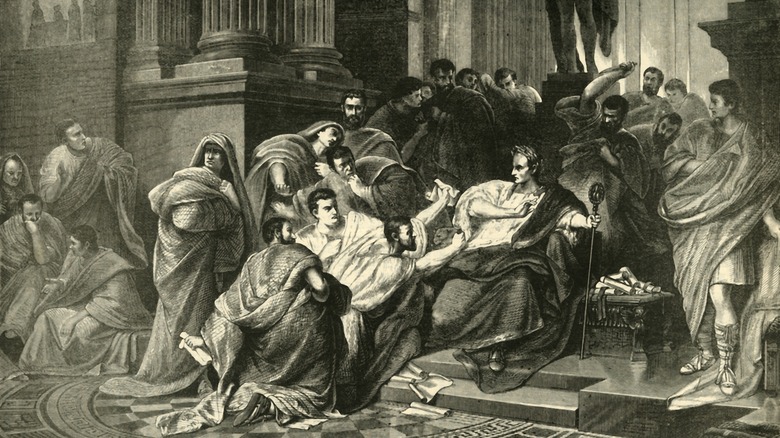

The Republic came crashing down with Julius Caesar’s power grab in 60 B.C. Sure, this resulted in his stabbing death on the floor of the Roman Senate by a group of senators. (Talk about cutthroat politics!) But even assassination couldn’t take the nation off its trajectory into imperial despotism. According to The Collector, “the Roman Senate saw dramatic changes to its composition, influence, and powers” over the many centuries of the civilization’s existence.

Surprisingly, the senators would outlive almost every other institution of Rome, including the vaunted emperors. Perhaps this makes their name even more fitting. You see, the word senator comes from the Latin term senex, which translates simply as “old man.” So, what did “Gladiator” get right about the senators? For starters, they’re accurately dressed and have the distinguished bearing, white hair, and beards you’d expect from these iconic “old men.” And a conspiracy to remove Commodus from power existed, according to the Los Angeles Times.

The complicated relationship between Commodus and Lucilla

To say the relationship between Commodus and his sister Lucilla was complicated is an understatement. But no historical evidence points to physical attraction between Commodus and his sister. After all, he had 600 sex slaves, a mistress, and a wife to keep him busy. But Lucilla did operate as one of the most influential and politically powerful women in the Empire, per Bust. And she did engineer a failed assassination attempt on her brother, which later resulted in Commodus having her killed. See what we mean by complicated?

According to the Los Angeles Times, she turned to the Roman Senate for support in killing her brother. Why had senators turned against Commodus? Certainly not based on ideological principles or an attempt to restore the empire to its former republican glory. Nope, Commodus raised their ire by increasing their taxes, becoming the “betrayer of his own senatorial class.”

The senators engineered their leader’s death by sending a dagger-wielding assassin after him as he walked through a dark passageway. As the assailant came in for the kill, he screamed, “This is what the Senate sends thee!” But his breath proved not only wasted but highly incriminating. Quickly disarmed and killed, the would-be murderer’s premature words contributed to the execution of many Roman senators, something you sure don’t see in “Gladiator.”

Gladiatorial competitions were wildly popular

Rome’s famed gladiatorial games proved just as savage and popular as the movie portrays them. They included men chained together and fighting in pairs, the introduction of starved and ferocious wild animals, trap doors, and much more (via the Los Angeles Times). And Ridley Scott had a field day including some of these elements in his film.

What’s more, the movie gets right just how popular certain gladiators could become. Perhaps this is best illustrated by the story of Flamma, a Syrian soldier-turned-gladiator (per Mental Floss). He proved so skilled and entertaining in the ring that Roman politicians offered him four chances at freedom. But addicted to the blood, adrenaline, and fame of the Coliseum, he refused. After all, History tells us that gladiators could quickly rise to the ranks as veritable sex symbols. (Gladiator sweat even got marketed as an aphrodisiac.) Unfortunately, Flamma’s love affair with the fame that came with the blade caused his premature undoing. By 30, he lay dead in the ring. Yet, the Romans so adored him that his face got minted on coins!

And if you think Scott’s grandiose vision of gladiatorial competitions proves a little over the top, think again. The Romans spared no expense when it came to entertaining the masses. Emperor Titus had the Coliseum filled with water in 80 A.D. to host a re-enactment of a naval battle involving 3,000 men.

The social status of gladiators

“Gladiator” focuses primarily on Maximus Decimus Meridus’ time as a slave compelled to compete in gladiatorial competitions. And this proved a historical reality for many who fought in the ring. According to History, Rome fueled its bloodlust, especially early on, by forcing conquered and imprisoned people into gladiatorial combat. Criminals who committed particularly nasty offences could also find themselves fighting for their lives before the masses. But a study of grave inscriptions from the 1st century A.D. points to an evolution of combatants.

Over time, free men started signing contracts to become gladiators. And could you blame them? I mean, Commodus himself couldn’t overcome the lure of adoring fans. These men came from various social classes stretching from impoverished individuals in pursuit of a lucky strike to ex-soldiers and even upper-class individuals and senators ready to show off their fighting prowess.

According to the BBC, “To the Romans themselves, the institution of the arena was one of the defining features of their civilisation.” When viewed within this context, it’s a little easier to see why men who never needed to be in harm’s way would give it all up for a chance to kill each other to satiate roaring mobs. (And the down payment they received upon signing their contract wasn’t a meager incentive either.) But a downside did exist. Gladiators who received money faced lifelong infamy as members of Rome’s disreputable professions, along with sex workers and actors.

Gladiators could and did win their freedom

One of “Gladiator’s” most beloved characters is Proximo, a former gladiator-turned-owner of fellow gladiators. He tells Maximus about receiving his freedom from Emperor Marcus Aurelius via the gift of a wooden sword. Known as a rudis or rudes, gladiators trained and sparred with them (via ThoughtCo.). When an individual decisively won a competition, securing his or her freedom, they received a rudis and a palm branch, symbols of newly won liberty.

One of the most interesting gladiator-related historical accounts comes from the poet Martial, who recounted two gladiators fighting for hours. Their well-matched bravery and skill won the hearts of the crowds and resulted in a stalemate. Then, the unthinkable occurred. Both warriors received a rudis and palm branch from the emperor.

What happened to retired gladiators? They forged a new profession. Some became farmers. Others went on to train future gladiators at a local school. The most fortunate warriors rose to the ranks of summa rudis, an elite group that wore white tunics trimmed with purple, denoting their standing. They carried whips or batons, using them to point out illegal maneuvers, and they ensured that “the gladiators fought bravely, skillfully, and according to the rules.” After all, strict rules of conduct existed despite Ridley Scott’s depictions of seemingly no-holds-barred events.

A Look At The Link Between Queen Elizabeth I And Shakespeare

How The Leader Of Scientology, David Miscavige, Rose To Power

Most Popular Ways People Entertained Themselves While Stuck at Home

The Untold Truth Of Methuselah

Why The Sex Pistols Are Suing Johnny Rotten

Where Is Making A Murderer's Brendan Dassey Today?

Don McLean's Daughter Details Years Of Alleged Abuse

You'll Never Guess The Pillsbury Doughboy's Real Name

The Scariest Creepypasta From Around The Internet

How Winston Churchill Really Felt About Gandhi