This Is How Japan Is Preparing For The 2021 Tokyo Olympics

It should go without saying that Japan’s plans for the 2021 Olympics have been a bit complicated by COVID-19. In 2021, the then-Prime-Minister-Abe-led government waited for the International Olympics Committee (IOC) to take the lead on whether to postpone or cancel the games. Eventually, the Japanese government threw up its hands and said, “Shouganai,” or otherwise put, “What are you gonna do?” (The New York Times has the full report). Of course, they were hoping for the game’s now-$15.4 billion preparation expenses (per the Associated Press) to not be wasted, while Tokyo Major Yuriko Koike insisted that the games not be postponed by more than a year (per the Japan Times). Meanwhile, not a single “Tokyo 2020 Olympics” sign, which has adorned nearly every commercial street in Tokyo for over 2 years, was taken down.

There were plans. Big plans. Tourist numbers were going to be at an all-time high of 40 million for the year, as the Japan Times says. Japan was going to wow the world with its technological savvy, with Tokyo full of self-driving taxis and multilingual robots, per the Financial Review. At the time of this writing, though, mere weeks before the Olympics, Japan is not only driverless-car-free and robot slave-less, it’s just beginning to roll out its vaccines. Per the NHK, no spectators will be allowed in any Olympic event.

Amid the concerns of politics and international reputation, money, and a pandemic, how ready is Japan, anyway?

An Olympic legacy of national pride, victory, and defeat

To really understand Japan’s preparedness toward the Olympics, and its general attitude toward the games, it’s important to place things in historical context. There’s a lot of pride at stake for Japan.

Back in 1964, Tokyo held its first Olympics following its reconstruction after World War II, as recounted by the Japanese Olympic Committee. Because of the events of the war, Japan had been banned from the Olympics in 1948 and was eager to reenter the world stage. The Japanese economy was surging. The country was trying to reconcile its early 20th-century fascist rhetoric of victory and power with its crushing atomic defeat via Little Boy and Fat Man. The country’s nationalist tenor was greatly hushed but quietly straight-backed. As an emblem of its then-present and future role on the world stage, Japan premiered its ultra-fast bullet train rail system, the shinkansen, at the 1964 Olympics, as Financial Review explains. To this day, the bullet train remains a cornerstone of transportation keeping the country connected.

Japan hosted the Winter Olympics in 1972 in its northernmost region, Hokkaido, and then again in 1998 in Nagano. It lost its bid for two Summer Olympics: 1988 in Nagoya and 2008 in Osaka. The Tokyo 2021 Olympics were always intended to be a means to reassert Japan’s relevance as a global entity exporting not only cars and video games, but plenty of soft cultural power, and invigorate an economy stagnant since the 1990s.

A host of new venues to host the games

On the infrastructure side of things, as the official Tokyo 2021 Olympics site shows, the city of Tokyo has prepared for the Olympics by building a new, main Olympic Stadium for use in the opening and closing ceremonies. The 68,000-person venue has a greenery-adorned exterior and was designed by renowned architect, Kengo Kuma. Its location is a bit odd, train-wise, but is couched between two parks, including the massive, multipart Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden. It’s also within reach of a few of Tokyo’s major shopping areas such as Shinjuku and the upscale Omotesandō .

Also on the list of venues, as the travel site, Tokyo 2020 and Beyond shows, Yoyogi National Stadium, which kind of looks like a pagoda roof, and the “spiritual heart” of martial arts, the Nippon Budokan, which will host one of Tokyo 2021’s Japan-only events, karate, near the Emperor’s Palace and palace grounds. We’ve also got the Ariake Urban Sports Park, scheduled for use in another of the 2021-only events, Skateboarding (per the Tokyo 2021 website), and the Aomi Urban Sports Center for the 2021-only sport climbing (indoor speed climbing) (also per the Tokyo 2021 website).

There were some difficulties in pushing these stadiums to completion. The Olympic Stadium, for instance, had its original, more costly design by Iraqi-British architect, Zaha Hadid, scrapped, as the Japan Times explains. There was also, as Nippon explains, a labor shortage that threatened to slow down construction.

Barrier-free access has slowly improved

Historically, Tokyo hasn’t exactly been accessible to those with mobility issues. Japan might have full, nationwide public transportation coverage and trains and buses are never any farther than 10 minutes on foot from anywhere within central Tokyo, but stations are often built deep and layered to withstand earthquakes and control floodwater. As a result, there are tons of stairs, everywhere, and many stations — and storefronts in a jam-packed urban cityscape — often lack elevator or ramp access. It might take 10 minutes or more to simply walk from the station mouth to its inner gates, which, in a dense, underground transportation-slash-shopping labyrinth full of hustling commuters and indecipherable signage is difficult enough on two, fully ambulatory legs.

All of this presents a problem for Olympic games officially named “Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games.” In fact, there are 23 Paralympic sports in the 2021 games, as Tokyo 2020 and Beyond explains. And so, Tokyo has attempted to push for better barrier-free access, all around. Many taxis now service those in wheelchairs. Many shops likely to be frequented by travelers, domestic or international, such as 7-11, have had ramps installed in the fronts or backs. Monolithic stations such as Shibuya have undergone design overhauls for better flow and elevator access. Finally, non-profits such as the Nippon Foundation Paralympic Support Center have been pushing hard to raise awareness of such issues and even built a dedicated Olympic training facility for para-athletes, the Nippon Foundation Para Arena.

Smoking, drinking, and porn: oh my

Visitors to Japan often remark on how easy it is to grab ahold of alcohol, tobacco, and pornography, regardless of age. Restaurants will never check IDs for age, and in grocery or liquor stores customers merely have to press a button at a register attesting to one’s age (the legal drinking age is 20 in Japan). Even vending machines sometimes carry alcohol, mostly outside of cities; just pop in some change and grab a beer. Same goes for tobacco: head to a vending machine and snag a pack of cigarettes. Pornography typically rests at knee- or waist-level on racks in convenience stores next to regular magazines about fashion or the economy, bound or wrapped, and very accessible to a tiny, filching child’s hands.

While alcohol and cigarettes are still likely buyable to intrepid and bold under-agers, especially if they’re within the vicinity of said vending machines, public smoking rules have undergone a significant overhaul. As of very recently, as described on Medium, smoking indoors in restaurants and bars has finally been made illegal (there are rare exceptions, but those places at least have designated closed-door smoking rooms). Smoking outdoors is also illegal unless folks stand in designated, walled smoking areas that basically look like shame boxes. As for porn, it was simply announced that convenience stores would stop selling it, as Medium also states. At the time of writing, this has yet to happen, but the amount per convenience store has noticeably decreased.

Day trips, tourist sites, and multilingual support

Because of COVID-19, no tourists are currently allowed into Japan. While this means that hotels, tourist sites, downtown restaurants, and other high-traffic spots won’t be making as much money as they would have liked, preparations have nonetheless been underway to make Tokyo more accommodating for non-Japanese speakers. Tourist-heavy hubs of neon lights and karaoke, such as Shinjuku, have come to sport English-language signage, in honor of our global lingua franca, and staff has begun deploying common English-language phrases like, “Will that be to-go?” In a country like Japan, where the common citizen, despite a rigorous domestic educational system, utterly fails at foreign-language proficiency, this is a huge step (the Tokyo-based, English-language magazine Metropolis has a good breakdown of this issue). At least one train company, Odakyu, has also implemented multilingual support for wayward travelers.

Sites such as Tokyo 2020 and Beyond contain an in-depth look at a multitude of tiny other ways Japan has been preparing for the Olympics (here), a loose timeline of Olympic events and locations as they relate to airports (here), day trips and in-city outings (here), and even a manners guide for non-Japanese folks (here). Other sites like Voyapon have developed full-on travel guides, available on the Voyapon website. Even if none of these measures can be put to use for international travelers at this point, such resources will still be available to folks in the future.

In the meantime, here’s hoping the games go off without a hitch.

Why Woodstock Would Not Have Happened Without A Farmer

How George Orwell Was Nearly Killed While Writing One Of His Books

The Real Story Behind Beijing's Sandstorm

How The Vatican's Secret Passageway Helped Save Popes' Lives

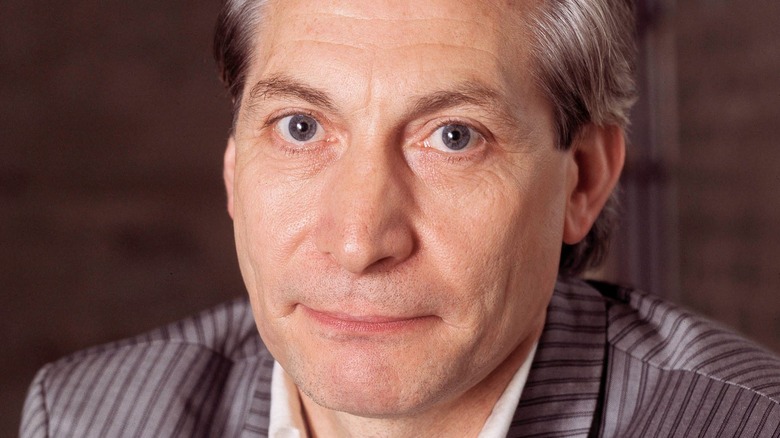

This Is How Charlie Watts Really Felt About David Bowie

The Psychology Behind Why People Join Cults

North Korea's Extreme Dating Rules Explained

This Is How DMX Really Got His Name

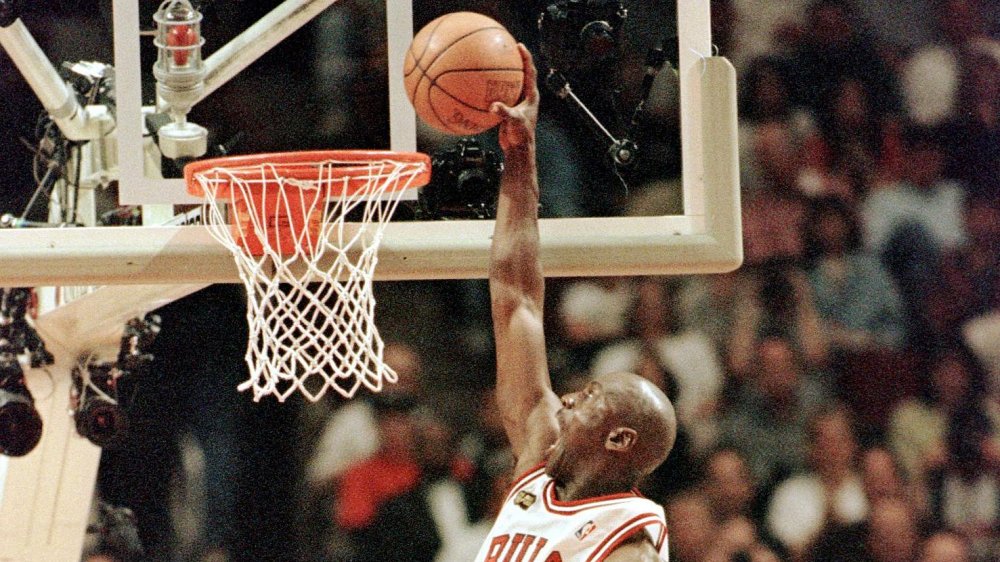

How Far Can Michael Jordan Dunk?

How Long Would It Take To Walk Across America?