Tricks The FBI Uses To Interview Serial Killers

The FBI has tried to disabuse the public that interviewing serial killers is much like Clarice Starling first looking Hannibal Lecter in the eyes for the first time through bulletproof glass. It does make for a better movie than the stacks of paperwork that follows any attempt at speaking to a killer, let alone the footwork that goes into making it worthwhile.

But that doesn’t mean that these interviews don’t happen or that there aren’t reliable tricks that the investigators use to get the worst people on earth to feel chatty. The FBI has had decades of practice perfecting the art of convincing a serial killer to work against his best interest to, in a sick way, do the right thing.

(If you are a serial killer who has yet to be caught, maybe it is best that you skip this feature and read something that will make you want to turn yourself in. No sense giving you tips.)

Why bother?

It might seem like a waste of FBI resources to keep interviewing these guys (with notable exceptions, serial killers tend to be men). The killers have already been arrested and, for many, admitted enough to be locked away for the rest of their lives, if not outright sentenced to death. No matter what they say, you can’t execute them twice, so why speak at all?

The killers often have information that the police need and their victims’ families want, such as the location of bodies or exactly how many victims there are. As is a surprise to no one, serial killers are not nice people and are not inclined to be forthcoming, particularly when they can taunt law enforcement by keeping information to themselves. For instance, according to the Los Angeles Times, Samuel Little was convicted of strangling three women in 2014. Investigators suspected there were more, but they lacked the hard evidence to prove it. They would only get their answers from Little himself. Through interviews, they were able to get him to confess to killing 90 women over 35 years.

Knowledge is power

Investigators do not go into the interview with many things they don’t know. They have reviewed every case file and memorized every grisly crime scene photo. Most questions the investigator asks, they already know the answer. It is a means either to get the killer to admit to the facts or lead them to confess something more. In an interview with Mental Floss, Former FBI special agent John Douglas said, “Before I go in to do an interview, [I] go back into the files and fully look at the case that got him or her incarcerated to begin with. … You want to be totally armed with the case when you go in.”

They want to be able to call the killer on any misinformation he might try to slip by, either to distract the proceeding or show how he is smarter than the law. (The killer did get away with killing up to this point, so he is sure that he is the sharpest person in the room). In pointing out where the killer is trying to deceive, investigators prove their mettle to the killer, make him more uncertain what the law actually knows and earns the killer’s trust.

No “good cop, bad cop”

The investigator doesn’t go in, guns blazing, threatening to assault the killer if he doesn’t start talking. John Douglas told Mental Floss that he asks questions “in a very relaxed kind of a format, making the subject … feel real comfortable and feel at the same time that they are controlling me during the interview.” He added to AETV, “I just kind of laugh and joke around with them, which totally changes things.”

The investigator is not the killer’s friend and doesn’t pretend otherwise, but they approach this dispassionately. They are casual in asking about the details of the killings, no matter how gruesome, though Douglas — the inspiration for Jack Crawford in The Silence of the Lambs — does not use words like “killing” and “rape” that place blame. For some killers, this is enough to earn the investigator some respect. To AETV, Douglas noted, “Some agents in my unit want to strangle the guys. Deep down, I’d like to strangle them, too, but I can’t.”

For other killers, this tack gets them to feel safe enough to start boasting. After all, they are not getting out soon. Why not be proud of what they’ve done?

The investigator tries to find a point on which they can connect with the killer. Is he a big sports fan? Does he read romance novels? Anything that will play upon mutual humanity helps loosen lips. Killers are unlikely to go into this fully believing the officers are human.

Who were they?

Before entering the room, the FBI has combed through anything they could find about the killer — purchase history, clubs they’ve joined, library records, places they’ve lived. It is challenging to know which detail will be important to the interview, but stitching them together gives the investigator grounding. This also facilitates finding a point where they can have a friendlier conversation to help the killer let his guard down. Douglas noted to AETV, “I can’t think of one who did not come from some type of dysfunctional family, whether they were abused or neglected.”

In a report by CBS News, Special Agent Katherine Nelson, who investigated Israel Keyes, said that they obtained “cell phone records, financial records, anything we could find out about his background, his travels. … Anything that would just tell us a better story about him.”

This can also help tie the killer to other crimes, either because of cold cases where they can be proven to have lived or crimes that seem to fit the same MO. (Unfortunately, in this field, there is the concept of the “less dead.” Killers are more likely to prey upon those who tend to slip through the cracks of public notice or caring, like transients, the homeless, and sex workers.)

Dr. Aysha Akhtar told Writer’s Digest, “serial murderers are still individuals with emotions and who respond to basic courtesies. … You must consider yourself a partner with the interviewee if you hope to get honest responses.”

Better have a good memory

The moment an investigator takes out a recording device, the interview grinds to a halt. Killers are often paranoid and do not want this to be part of the permanent record (this is not universal — some killers desperately want the world to know what they did as a sort of immortality). In Mental Floss, John Douglas said, “If my head is down, [they’ll ask], ‘What, are you taping this? Why are you writing these notes down?’ … It’s going to be key [for] me to maintain some eye contact …”

The same goes even for a pad of paper and a pencil. The interview’s focus becomes what is being written about, why the interviewer found those words so interesting, and possibly how to make the investigator write down nonsense and lies.

The interviewer has to treat this as a conversation and nothing more. Both parties know why they are there, but that sense of relative informality is the only thing that is going to get information to flow. The killer has to be a subject in the conversation, not the object of an interrogation.

According to AETV, teacher-turned-murderer Joseph McGowan wrote to a pen pal, “During the interview, I looked down and noticed this guy Douglas wasn’t taking notes. But he knew more about the case than anyone who’s ever spoken to me.”

Killers lie

Once the investigator teases a confession out, their job has only begun. As Michael Berry, senior lecturer in forensic pathology, noted to The Independent, “They are going to play lots of games, offer the police things and then not come up with the goods.”

Any information killers give is picked apart and compared against the facts. John Douglas said to Mental Floss, “If [an interviewer relies] on self-reporting, they’re going to be filled with a lot of lies coming from the person they’re interviewing.”

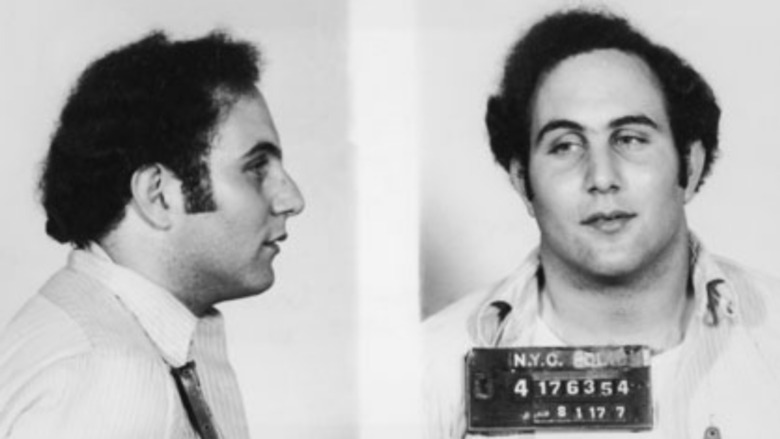

Killers are more likely to have mental illnesses that lead to having a loose relationship with the truth. Douglas affirmed this to AETV, saying, “The majority have antisocial personality [disorder] or are psychopaths. They know right from wrong, they just don’t care.” Visionary killers like David “Son of Sam” Berkowitz, for instance, believe they are compelled to kill by an outside force. Missionary ones think they are doing the world a favor by purging it of undesirables. Hedonistic criminals just enjoy killing. None of them make sense to the healthy members of society. (People with mental illnesses are far more likely to be the ones murdered, however.)

Sometimes, the killers lie just for the fun of making a fool of the FBI. Others, it is self-serving, such as claiming to know where a body is but will only show them, not tell them. The killer gets a field trip in the sunshine, getting fast food, and watching officers muck about in a bog.

Investigators tell the truth

Though the killers should be assumed to speak only in lies, the investigator doesn’t. Even when it might be easier, the investigator sticks as close to the truth as possible. If they claim to have a piece of evidence that the killer knows they don’t, all the trust is destroyed, and the killer won’t be any more forthcoming (and certainly not honest). Killers hate the idea that someone might be trying to trick them, that someone could be playing the same game they are.

Even beyond the case’s facts, the investigator never promises the killer anything they cannot deliver. The killer can make his confession contingent on getting a reduced sentence, but that is not a request the investigator can necessarily grant. They can tell the killer that they will see what they can do, but promising something that doesn’t happen will shut the killer down. Again, killers need to feel they have power. Broken promises make them realize how weak they are. These promises are not always demanding more privileges or reduced punishment. Serial killer Israel Keyes said that he would only fess up if the interviewer promised that they would tell him his date of execution, according to CBS News. All the interviewer could say is that, the more Keyes told him about killing people, the likelier it was that the jury would want to give him a death sentence.

A team affair

It is not one — or even a few — people prepping for the interview. Though, to not overwhelm the killer, only one or two agents usually go in, and these agents have a large team of analysts and profilers at all levels behind them.

This large team focuses on the detective work that provides the interviewer with the background they need to be most effective. People peruse old news stories, cold cases, interviews with people who knew the killer as far back as they can go — even talking to elementary school teachers if that is what it takes.

Even though Samuel Little confessed to 90 murders, the Los Angeles Times reported that the police could only corroborate 36 and were, as of 2018, vetting the rest. Killers, after all, are not trustworthy by nature. Kevin Fitzsimmons, an analyst for the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program, said, “Law enforcement has verified he did these things. It takes a lot of work, but we are doing it.”

It is rarely only one interview, but a series of them, each built upon the information (or lack thereof) that the killer provided last time. By the time that the interviewer speaks to the killer, they want to know the killer better than he knows himself. Israel Keyes, for instance, gave two dozen interviews to several investigators over seven months, according to CBS News, giving only morsels each time, until they had a handle on the immensity of his crimes.

Get cozy

Unlike what the media would show us — all harsh light and bare room — the investigator tries to use the environment to their advantage. They cannot provide the killer anything that could be turned into a weapon, but they do what they can to make it comfortable and cozy. They want the killer to be as relaxed as is possible under the circumstances. A tense subject, one visually reminded that they are in prison, will not feel chatty.

John Douglas told Mental Floss that he swears by this. “If I’m dealing with a real paranoid type of individual, I need to put this person near a window — if there’s a window — so that he can look out the window and psychologically escape.”

Douglas says that even his posture plays a part in setting the killer at ease. He looks entirely in his element and composed, “like on a date kind of thing.” He doesn’t cross his arms over his chest or sneer, even when he hears the worse information anyone ever could. He is clear on his purpose, but he uses the room and his own demeanor to suggest to the killer that they are both working toward the common goal of getting his story out of him, and that they are on the same side.

The way to the truth is through the stomach

Sometimes, the interviewer will enter the room with coffee, asking the killer if he wants something. In an interview on Serial Killer Info with Robert Pickton, the first recorded words were about the freshness of the orange juice that morning. Food naturally sets people at ease, makes the interview seem more casual, and subtly suggests to the killer that the interviewer is looking out for them and can get them what they want. Even if the killer declines, the seed is planted in his mind.

The food they can get in interviews — and certainly that they can ask for what they want — is a sight better than depending on the prison cafeteria. It gives the killer a reason to look forward to being interviewed and provides more incentive to start talking since more information means more M&Ms. In a report by CBS News, Special Agent Jolene Goeden said that Israel Keyes only gave information in exchange for food and tobacco. “He wanted an Americano coffee from Starbucks. … He wanted a Snickers bar, and he wanted a particular cigar.”

Even when they allow the prisoner out (with much supervision) to point out where bodies might be or scan an area to see if anything is familiar, they stop for food. Though no one pretends to be friends, it is hard for the killer to be too angry at the guards and investigators while drinking a milkshake.

Use the killer's arrogance

The investigator is a master of psychology, subtly using what they know about the killer to get him to talk. Like Ted Bundy, some killers are only too eager to be goaded into bragging about how clever they were, how they evaded the police, or tricked their victims. They want their fame. According to John Douglas’ interview with Mental Floss, the killers basically say, “‘But I’m the main guy, right? You’re doing this research and you guys got the real McCoy here. I’m the best and the worst of the worst.'” (Accord to NPR, Samuel Little wins that revolting award in the United States. Semana claims that title internationally for Luis Garavito.) Of Israel Keyes, Special Agent Jolene Goeden said to CBS News, “he wanted to tell this story. He wanted to talk about what he did.”

Others were driven by feeling inadequate, possibly due to having been abused as children, according to Douglas to AETV. They will need a gentler touch and are inclined to minimize their number of victims and justify why they did it.

Rarely do the killers want to put their victims’ families at peace by finding the bodies (or even admitting that he was the killer). Often, they do not even regard their victims as people. Little only talked with investigators because he wanted to relive his crimes, according to the Los Angeles Times, and could become angry when it was reframed as helping his victims’ families.

Let him hold the cards

Once the killer is in the interview room, he has little power left. They are never going to be free again. They have lost access to what made them feel powerful. The investigator lets them think that they have power in the interview.

And they do. As Dr. Aysha Akhtar put it to Writer’s Digest, “[I]f they are not getting anything out of the conversations, why should they bother with you?” These interviews are voluntary. The killer can ask to be taken back to his cell if annoyed. The interviewer cannot keep him there.

However, sitting alone in a cell is likely to be more boring than chatting about your favorite hobby with an interested party whom you can try to shock with your deviance, a person who can get you a latte if you ask for it. The Independent quoted Keith Hellawell, a senior officer who interviewed the Yorkshire Ripper, as saying, “They tell you what they want you to know and to some of them … it was a game.”

The investigators know never to lord over their interview subjects, even though they are always the ones with the control. According to Mental Floss, when 5-foot 2-inch Charles Manson sat on the back of his chair to seem taller, John Douglas let him. He went on to say, “I know you hate me, but go ahead and do it. I’m just trying to get a little bit of information now.”

Disturbing Details Discovered In Lucille Ball's Autopsy Report

Why Nirvana Was Kicked Out Of Their Own Album Release Party

The Real Reason The Roman Colosseum Was Abandoned For Centuries

What Really Happened During The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War?

How American History Classes Lie About D-Day

The Bizarre Reason A Virginia Man Sued Himself For $5 Million

The Truth About The Longest Piano Masterpiece Ever Produced

What Is Manna?

Why People Don't Believe Son Of Sam Killed Alone

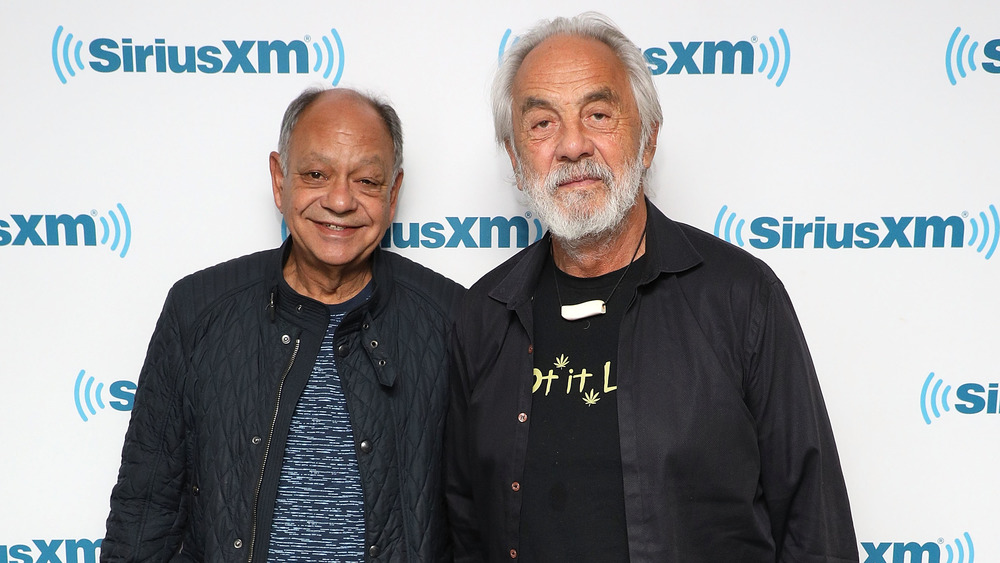

Cheech And Chong's Net Worth Is Higher Than You Might Think