What It Was Like Taking Part In The Oklahoma Land Rush Of 1889

With the announcement of the Oklahoma Land Rush on March 3, 1889, America prepared for its last hurrah in the unsettled lands of the Wild West. Just a year away from the official closing of the frontier with the 1890 Census (via PBS), millions of acres of unassigned Indian Territory enticed settlers from all over the world. According to Historic Fort Reno, the settlers gathered there to prepare for an event like no other, a literal sprint for acreage. The world had never seen anything like it, and tens of thousands of people gathered to participate in late April.

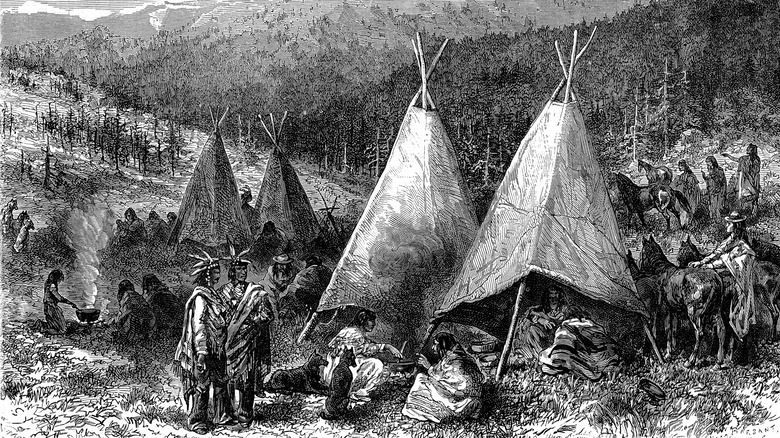

What made these lands prime pickings for settlers? Unlike other federal lands designated to specific Native American tribes, the “unassigned lands” remained a common area for the roughly 40 Native American tribes that the government had relocated, starting with the Trail of Tears. Once thought useless, various factors conspired to make this land suddenly coveted by settlers, from tech innovations to land-hungry waves of immigrants.

But what was it like to participate in the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889? The answer to this question differs based on who you were, how much capital you could devote to the effort, and how fast you could hoof it across the prairie. That said, people from just about every walk of life participated, carving their own piece of heaven out of the treeless landscape (and paving the way for the Dust Bowl). Here’s what you need to know about the Oklahoma Land Rush.

The race started with a boom

At noon on April 22, 1889, cannon booms, bugle calls, and pistol shots ushered in the Oklahoma Land Rush, as reported by Indian Country Today. How many ultimately participated in the event? Historians estimate between 50,000 and 60,000, hellbent to get a 160-acre piece of the two million “unassigned” acres up for grabs.

As reported by the Oklahoma Historical Society, the thousands of settlers poised along the line raced headlong into “unclaimed lands,” searching for the perfect place to build their homesteads. The air was alive with the sounds of spurs and thundering horse hooves. Wagons kicked up clouds of dust, and settlers cracked their whips, ripping across the plains. Racers looked to surveyors’ cornerstone markers to find the perfect plots and then plant stakes bearing their locations and names. From there, they either headed to the land office to register their claims or began making minor improvements to the land per the Homestead Act.

The federal government dispatched Buffalo Soldiers for crowd control. Comprised of six African American infantry and cavalry regiments, they served mainly in the American West. But much of the designated “Land Rush” area remained thinly manned by troops. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, “A cavalry troop from Fort Sill arrived at Purcell on the day before the run, far too late to contain the settler mass from spreading out to unmonitored points, like 7-C Flats, along the eastern and southern boundaries.”

Paving the way for the Oklahoma Land Rush

How did the United States have nearly two million acres of unclaimed land at its disposal as late as 1889 (via History)? Unlike other parts of the nation, non-indigenous settlers had no access to these so-called “unassigned lands.” Instead, they comprised part of the communal landholdings of tribes such as the Apache, Creek, Cheyenne, Choctaw, and more. But this changed with the announcement of the Oklahoma Land Rush.

“Initially considered unsuitable for white colonization, Indian Territory was thought to be an ideal place to relocate Native Americans who were removed from their traditional lands to make way for white settlement,” per History. But advances in agricultural technology by the late 19th century convinced some settlers that these previously “unassigned lands” could prove lucrative. The land sat vacant post-Civil War, designated for the settlement of Plains Indians and other Native American nations yet to experience relocation, per the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Potential settlers saw this as an opportunity to lay claim to new lands, and they had legislative backing to assist their case. For example, the 1887 Dawes Act privatized Native American land, beginning the slow stripping of territory from tribes. But only after the “Boomers” lobbied President Benjamin Harrison did the deal get clinched. It came in the form of the Indian Appropriations Act of 1889 (aka the “Sooner clause”), which permitted settlers to enter and claim the “unassigned lands” (via the National Park Service).

Speed was the name of the game

While many settlers relied on fleet-footed steeds, about one-third took “Boomer trains” into the heart of the unassigned territory (via the Oklahoma Historical Society). Operated by the Santa Fe Railway, these trains were not permitted to travel faster than horses. That way, they ensured a fair and equitable distribution of land, free from technological manipulation.

These train-riding “Boomers” converged at two locations, Purcell and Arkansas City. At Purcell, passengers flooded railcars, vying for top dog positioning. Many optimistic land seekers also lined up in Arkansas City. Townsite companies and settlers also flocked to railroad stations in Oklahoma City, Verbeck (modern-day Moore), Guthrie, and Norman. Although the 1889 Land Rush placed a primary focus on securing agricultural plots for homesteading, a significant number of individuals had their sights set on establishing city centers.

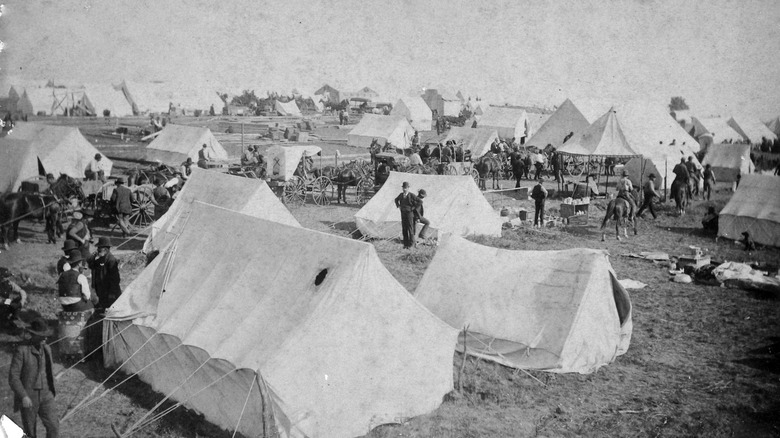

These included companies such as the Seminole Townsite and Improvement Company, founded by members of the Santa Fe line. They received early access to the “unassigned lands” to survey potential townsites. Other groups also got in on the action. The result? According to History, cities like “Guthrie had been transformed from a small railroad station to a tent city of 10,000 people in just hours. By nightfall, more than 11,000 agricultural homesteads had been claimed during the Oklahoma Land Rush.” Conflicts about town lots sold to settlers by more than one company would soon ignite.

What was the deal with Boomers and Sooners?

Despite the U.S. military presence, some settlers managed to sneak into the unoccupied lands early. There, they hid until the Land Rush officially began. Known as “Sooners,” they hoped to secure choice pieces of land ahead of the main event. According to the National Park Service, the presence of Sooners, as well as multiple claims to the same properties led to hundreds of lawsuits.

Besides dealing with Sooners, the Oklahoma Land Rush also brought out another archetype that would be honored by some and disparaged by others, the “Boomer.” According to NON DOC, “In the late 1870s, Boomers, notably led by David L. Payne (until his death in 1884), were so named because they were ‘booming,’ or making considerable noise, about opening Indian Territory to Anglo settlement.” But they did more than make noise. Many illegally camped in Indian Territory, attempting to claim land prematurely and unfairly.

In other words, Sooners sought an unfair advantage and refused to follow the rules, while Boomers focused on stealing land secured via hundreds of treaties from Native American tribes. Historically, both came with an air of criminality: “Calling someone a Sooner could get you killed, whereas the Boomer label carried with it a faint whiff of pioneering spirit,” per NON DOC.

The Oklahoma Land Rush had an international flavor

Who participated in the Oklahoma Land Rush? According to History, individuals from all over the world, including recent immigrants from England, France, Scotland, and Ireland. Why did these immigrants move to the United States? For a variety of different reasons.

French immigrants often fled the turbulent political and economic climate of 19th century France. And as for British immigrants? Moving around had become a habit. As reported by Gale, “From moving down the street, across the country or overseas, migration was a common experience in Britain during the nineteenth century — not only for native Britons, but also for substantial numbers of immigrants who chose to make their homes in Britain.”

That said, authors Karen Maguire and Branton Wiederholt argue in their paper “1889 Oklahoma Land Run: The Settlement of Payne County” that most land rush participants proved American-born. Maguire and Wiederholt describe them as, “Many thousands strong, the boomer, the settler, the gambler, the speculator, the land shark, the honest home seeker, the adventurer.” No wonder federal troops had their hands full enforcing the Sooner clause, which prohibited individuals from arriving to occupy the land before the president’s proclamation date.

Women enjoyed new land ownership opportunities

Although women still lacked the right to vote in the United States, they could participate in the land rush, as reported by the Oklahoma Historical Society. While married women generally followed their husbands, widowed and single women headed out on their own. Any woman 21 or older could claim a 160-acre homestead as head of household, and both white and African American women took part in the land rush.

What were these women like, and what brought them to Oklahoma? According to Arrell M. Gibson, an Oklahoma historian, the frontier women involved in this event were “resourceful, inventive, creative and versatile.” These women would also exercise a significant influence in their new home. Not only did they act as wives and mothers, but they also rose to the ranks of politicians, lawyers, and more.

Many of these talented and influential women recorded their stories in journal entries and autobiographical works. Through these writings, historians have gained a wealth of knowledge about what life was like in Oklahoma’s land-boom towns.

African Americans looked to a bright future in Oklahoma

How many African Americans participated in the land rush? It’s hard to know for sure, but 1,365 Black individuals lived in Oklahoma one year after the rush. What’s more, between 1865 and 1920, more than 50 all-Black towns and settlements were established across the “unassigned” lands.

Why did Oklahoma see an early and prolific establishment of so many all-Black towns? It represented a natural extension of the Trail of Tears, which displaced the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes.” You see, some Native Americans involved in the Trail of Tears were slave owners, and they used the cover of Indian territory to keep up the abhorrent practice, according to the University of Tulsa. “The Five Civilized Tribes were deeply committed to slavery, established their own racialized Black codes, immediately reestablished slavery when they arrived in Indian territory, rebuilt their nations with slave labor, crushed slave rebellions, and enthusiastically sided with the Confederacy in the Civil War” (via Smithsonian Magazine).

Besides establishing African American communities in the aftermath of Native American slaveholding, the 1889 Land Rush also attracted more African Americans into the territory. The Oklahoma Historical Society’s cultural diversity curator, Bruce Fisher, notes in an interview with The Oklahoman, the prominent presence of African Americans in all of Oklahoma’s land rushes. As these settlers poured into the region, they established newspapers advertising the state as a “promised land.”

Native Americans saw it as a 'desperate, dark day'

While many settlers looked to the Oklahoma Land Rush with excitement, seeing it as an opportunity to create a brighter future, Native Americans perceived it very differently. According to Daniel Swan in an interview with Indian Country Today, the land rush “further marginalized” these populations and represented a “desperate, dark day.”

To accommodate the land-hungry, non-indigenous settlers, more than 375 treaties made with various Native American tribes were broken. Once upon a time, these treaties had forbidden settlers from entering Indian Territory (via The Conversation). But with the realization that the land protected by these treaties had commercial value, everything changed in a matter of a month, leaving the Natives reeling as the land they once shared disappeared. The last land rushes ushered in beginning in 1889 also coincided with the official closing of the frontier, which meant for the first time in history, Americans no longer had greener pastures to dream about, per PBS.

What significance would this have moving forward? According to Frederick Jackson Turner, a young historian, “The frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.” Without distant wildernesses to conquer, how would Americans maintain their vitality and “rugged individualism?” Nobody knew. But with two million acres left to claim, settlers turned their attention to the veritable “final frontier” with a gusto.

Asian perspectives on the Oklahoma Land Rush

Among the first Asians to settle in Oklahoma were the Chinese, as reported by the Oklahoma Historical Society. Some historians argue these individuals may have had familiarity with the unassigned lands while working for the Southern Kansas Railway, a line constructed from Kansas through Oklahoma between 1886 and 1887. Others may have arrived as laundrymen and cooks employed by the US Army in 1889.

Where did these Chinese immigrants go? They arrived in places such as Guthrie around the time of the 1889 Oklahoma Land Rush. By the end of that year, the city boasted five laundries that were Chinese-owned and operated. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, many of these immigrants also opened restaurants.

Soon, Oklahoma City boasted a small Chinatown, which would continue to grow through the 1920s. What do Census records tell us about the Asian presence in Oklahoma? They fail to provide a full picture, which has left many historians scrambling for an accurate count. For example, according to a 1921 check by a journalist and Health Department workers, Oklahoma City’s Chinatown had approximately 200 residents, “but the Census had recorded only 110.”

Jewish settlers during the Oklahoma Land Rush

History also points to the presence of Jewish settlers during the Oklahoma Land Rush, according to the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. They flocked to the territory, drawn to the fact land claims required nothing more than hard work. The opportunities afforded in the Oklahoma territory marked a distinct departure from other parts of the world, where religious stipulations muddied the waters of land ownership.

As Jerry Klinger notes, “The six great land rushes in Oklahoma, between 1889-1895, transformed the future state. An unknown number of Jews moved and settled in and around the developing communities, towns and emergent cities such as Ardmore and Muskogee.” What kinds of jobs did these new Jewish immigrants fill? Some owned their own ranches and farms while others chose a more urban lifestyle. These latter individuals built reputations and fortunes by providing the bare necessities and more, from baked foods to restaurant fare, tailoring and clothes-making services to various retail enterprises.

These Jewish immigrants flourished in Oklahoma, creating prosperous farms and businesses. Some rose to prominent positions as politicians and community leaders. They established organizations, business infrastructure, and synagogues.

A mixed reception to the Oklahoma Land Rush

National and international settlers cheered the Oklahoma Land Rush, according to History. They charged headlong into the fray with the promise that five years of hard work would result in free and clear land ownership of 160 acres. Because Oklahoma’s cities sprang up quickly, they lacked the social stratification that metropolises did back East and in other parts of the world.

This lack of stratification meant individuals got judged by their contributions and abilities rather than their religion, ethnicity, or other traditional markers of class structure. As a result, a variety of immigrants thrived, establishing robust enterprises and international communities. But the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 marked a dark day for Native Americans who found themselves further stripped of land and confined to reservations.

It also brought the worst out in some participants, including the Sooners and Boomers, as discussed by NON DOC. Both groups had no qualms about breaking the rules and stealing what was never theirs. While Sooners would retain a lousy reputation, Boomers tended to be seen in a more ambivalent light. However, both groups proved instrumental in robbing Native Americans of lands once promised to them by the Federal government.

How Skulls Were Once Used As Medicine

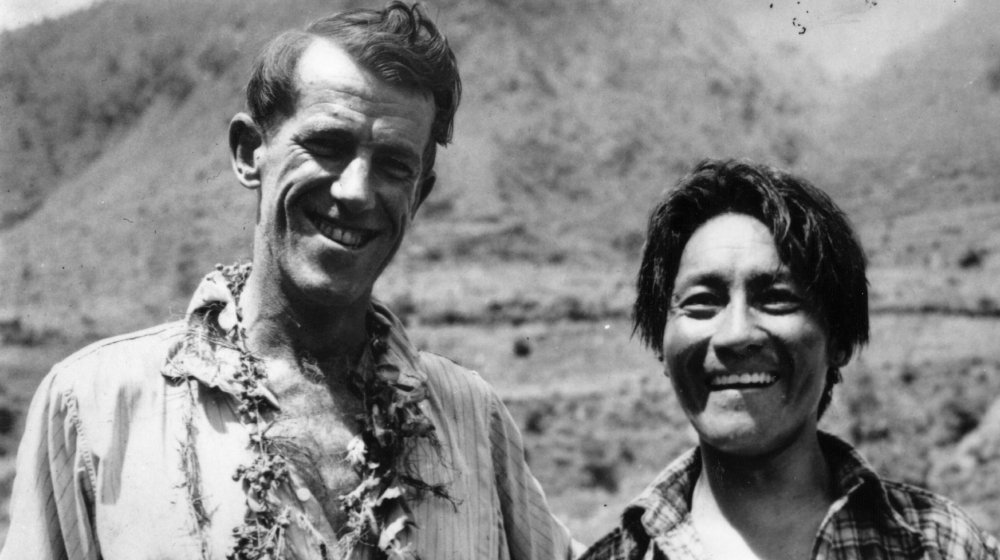

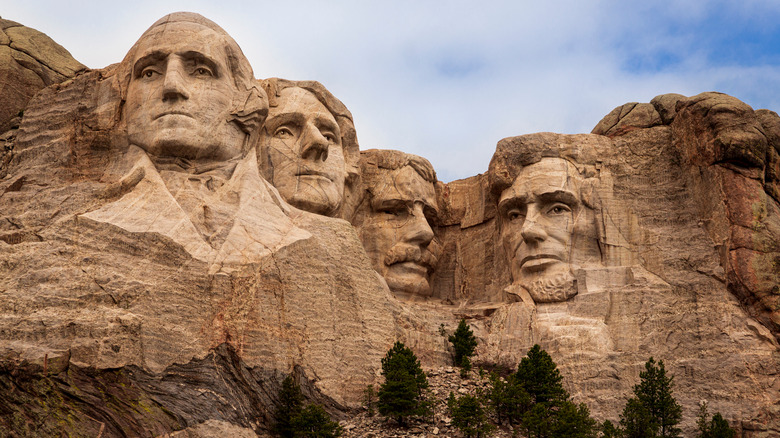

The Time Mount Rushmore Had A Baseball Team

The Truth About The Peaceful Saddam Hussein Heist

The Untold Truth Of Sirhan Sirhan

How Elon Musk Really Feels About Nikola Tesla

The Tragic Death Of Harpo Marx

How Building The Palace Of Versailles Helped Advance Science

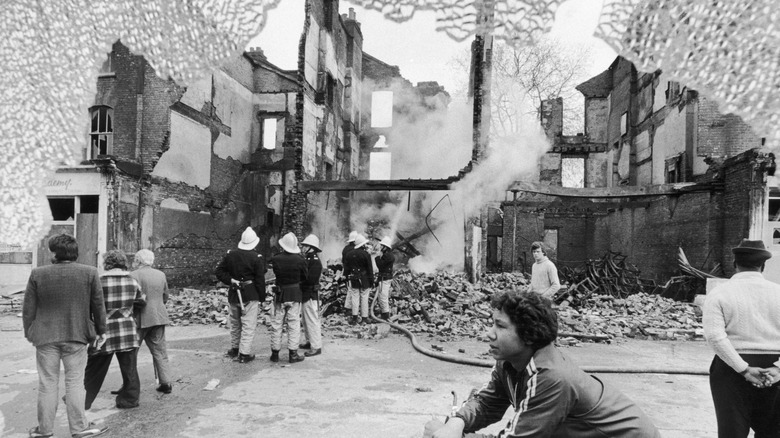

The Tragic True Story Of The 1981 Brixton Riots

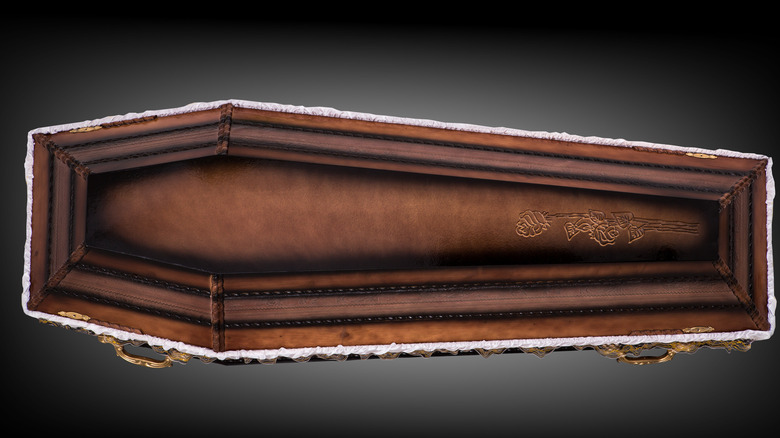

This Is The Difference Between A Coffin And A Casket

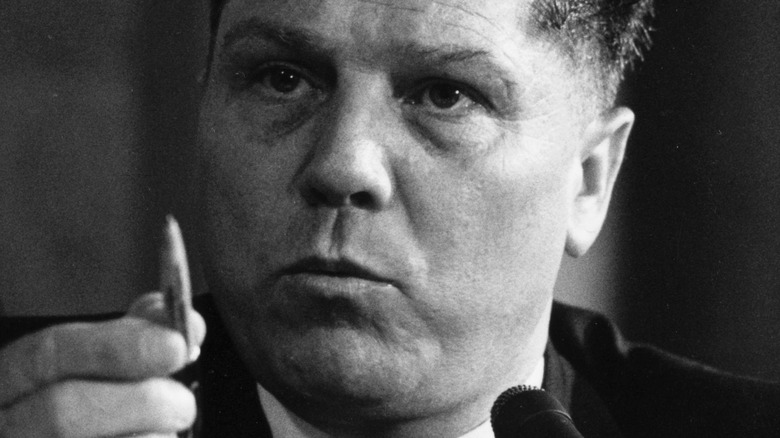

The Truth About Frank Sheeran And Jimmy Hoffa's Relationship