What Really Happened With That Huge Earthquake In Haiti?

Known as Douz Janvye in Haiti, the 2010 earthquake devastated the people of Haiti. Over a million people were left without homes, hundreds of thousands of people died, and several hundreds of thousands were injured.

Although there was a flood of international aid and relief sent in response to the earthquake, the people of Haiti received hardly any of it. Private contractors and nongovernmental organizations (NGO) ended up receiving most of the funds, and with little transparency and accountability, it continues to be unclear exactly what happened with all the money that was meant for Haiti. The introduction of humanitarian aid also ended up doing more harm than good.

Ten years after the earthquake, people in Haiti continue to struggle. Foreign governments direct their aid based on prioritizing private sector interests, and over a quarter-of-a-million people remain displaced with no running water. Local efforts have achieved the most when it comes to helping the people of Haiti, but with the government squandering funds meant for infrastructure, the people of Haiti have had difficulty rebuilding the country. This is the story of what really happened with the earthquake in Haiti.

Seismic activity of the area

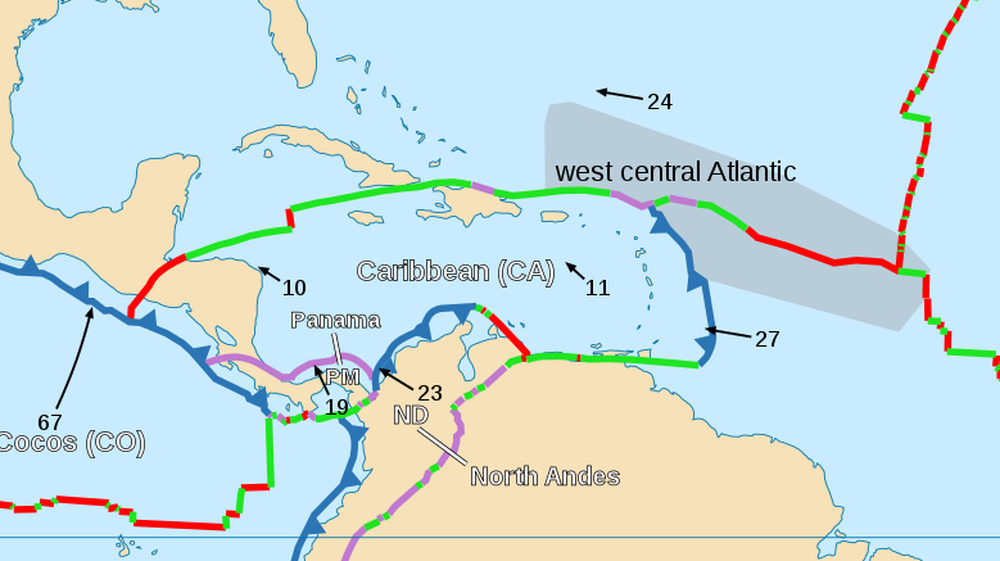

The island of Hispaniola, shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic, lies on top of a tectonic plate boundary in the Caribbean Sea. The top of the Carribean plate and the bottom of the North Atlantic plate run along the top of the island of Hispaniola, where the two plates move against one another horizontally creating seismic disturbances. The most prominent fault line of the two plates is the Puerto Rico Trench, which is the deepest part of the Atlantic.

According to Berkeley Seismology Lab, the island of Hispaniola has the Septentrional Fault running along the north coast, as well as the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden Fault running through its southern part. As a result, earthquakes have been recorded multiple times in the region throughout history.

The 1842 earthquake that struck Cap-Haïtien was the worst earthquake in Haiti’s history. According to The University of the West Indies, the earthquake had a magnitude of 8.1 and resulted in the death of 5,000 people in Cap-Haïtien, roughly half of the port city’s population. In Port-de-Paix, a neighboring city, the sea was recorded to have withdrawn 200 feet and then returned to bury the city under 15 feet of water.

It’s believed that the first recorded earthquake on the island in 1564 matched the intensity of the 1842 earthquake, but there were also several severe earthquakes throughout the late 1700s. Founded in 1749, Port-au-Prince suffered damage almost from its inception when it was destroyed in the 1751 earthquake.

The initial quake

At 4:53 p.m. on Jan. 12, 2010, Haiti was hit by a magnitude 7.0 earthquake. The epicenter of the earthquake was roughly 15.5 miles southwest of Port-au-Prince, and its resulting destruction radiated across Haiti. Estimates for the death toll range from 85,000 to 300,000 and over 1 million people were displaced. However, exact estimates for the death toll are unfortunately difficult to come by.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, it’s estimated that “60% of the nation’s administrative and economic infrastructure was lost, and 80% of the schools and more than 50% of the hospitals were destroyed or damaged.” In Léogâne, near the epicenter, roughly 80-90% of buildings were damaged or destroyed. The reason that the quake had such a devastating effect was because it occurred just over 6 miles below the surface, a relatively shallow depth.

The shocks of the earthquake were felt throughout Haiti and the Dominican Republic and reached as far as Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and Cuba. However, according to NPR, there wasn’t much damage on the Dominican Republic side of the island. Much of the damage wasn’t seen until the outskirts of Port-au-Prince. But getting “closer and closer into the heart of the city, things just got worse and worse and worse.”

The aftershocks of the quake

Within 20 minutes after the main shock, there were two large aftershocks of magnitude 6.0 and 5.7, respectively. Another aftershock occurred eight days later, with a magnitude of 5.9, which led to the collapse of many buildings that had already been damaged by the main quake. Some of the biggest reasons why so many buildings were destroyed during the main quake and aftershocks included the building codes and construction materials that were used.

It costs roughly 10-20% more to build an earthquake-resistant building, so “these added costs made safe construction an unaffordable luxury” (via Inside Disaster). Combined with few building codes, many buildings “were brittle and had no flexibility,” according to seismologist Ian Main, resulting in catastrophic damage when the earthquake hit. In the end, one in seven people were suddenly homeless. Unfortunately, many buildings in Haiti still aren’t earthquake-resistant, including the building that houses the earthquake surveillance units.

According to Wired, although the frequency of aftershocks is supposed to decrease over time, it’s possible that the aftershocks continued for years. At most, it’s possible that the aftershocks continued until 2018, when a magnitude 5.9 earthquake hit Port-au-Prince again.

The destruction of Port-au-Prince

Haiti’s capital and most populous city Port-au-Prince suffered some of the most damage. It was estimated that in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area alone over 150,000 people died. Countless buildings disintegrated, trapping or killing the people inside. Many other buildings like the National Palace, the cathedral, and the United Nations (U.N.) headquarters suffered heavy damage and caused dozens of fatalities.

According to NPR, “it was almost as if a bomb went straight to the heart of Port-au-Prince.” People were fleeing days after the main quake, trying to escape what remained of the city. And before the earthquake, one-in-four Haitians lived in Port-au-Prince out of a population of 10 million, which meant that upwards of 3 million people were affected by the earthquake.

The main quake also produced at least two tsunamis that reached 9 feet high and, according to Nature, in Port-au-Prince the waves rushed at least 230 feet inland. Over 200,000 homes were damaged, and over 100,000 homes were completely destroyed. According to reliefweb, at least half of Haiti’s schools were also badly damaged or destroyed. The three main universities were almost completely destroyed too.

Many hospitals were destroyed, and efforts to get aid in were hampered by key roads blocked by debris. Communications networks were also heavily affected, and with limited runway space, relief efforts were repeatedly obstructed.

Attempts to recover people

Despite aid coming to Haiti, much of it was unable to reach people in time. And while hospitals had open beds in northern Haiti, there was little-to-no way of getting people there from Port-au-Prince.

During the week after the earthquake, the search and rescue teams pulled over 130 people out alive from the collapsed buildings. Almost 2,000 people and over 150 dogs went through the ruins of Port-au-Prince and other villages and towns looking for anyone who might still be alive.

The government also provided free transport to other cities, and within a week, over 100,000 people left Port-au-Prince. But according to The Guardian, the Haitian government ended its rescue efforts ten days after the earthquake, deciding that it was unlikely that many would have survived after being trapped for so long.

Although Nick Birnback, a spokesman for U.N. peacekeeping operations, claimed that rescue teams would continue to work, the plan was to start shifting focus from rescue to recovery. With thousands of bodies in the rubble, it became a priority “to remove bodies and clean up affected areas to avoid health hazards and the spread of disease.” But Haiti’s morgue had overflowed quickly, and thousands ended up buried in mass graves.

The U.N. brings a cholera epidemic to Haiti

In October 2010, the U.N. relocated several U.N. peacekeepers from Nepal to Haiti to help with the earthquake. Unfortunately, the U.N.’s failure to screen for cholera led to the eruption of an epidemic just a few months after the earthquake.

According to Humanitarian Aftershocks in Haiti, by Mark Schuller, genetic and epidemiological evidence confirms that infected U.N. troops were the source of the cholera outbreak in Haiti. Although killing over 10,000 people — and some studies claim that the number might be three times as great – a few days before the five year anniversary of the earthquake, a judge ruled that the United Nations was immune from responsibility. In December 2016, the U.N. issued a carefully worded apology that admitted the U.N.’s culpability but maintained that “there continues to be an explicit refusal to accept any formal responsibility, let alone legal responsibility” (via The Guardian).

But despite the fact that immunity has been granted, the U.N. continues to “deny legal responsibility, refuses to establish any procedure to resolve the disputes over its responsibility, and is blocking all other attempts at resolution.” Although it appears that the last reported case of cholera in Haiti occurred in January 2019, almost all of the public health work around the epidemic was done by local health workers, with the U.N. playing a negligible part.

In 2019, the United States Supreme Court declined to review the issue.

Canceling Haiti's debt

After the earthquakes, several countries such as Venezuela wrote off Haiti’s debts in an attempt to prevent the country from falling into a debt crisis. By July, both the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank had canceled Haiti’s debt. But according to the Jubilee Debt Campaign, despite the cancelation of Haiti’s $1.3 billion debt, new construction funds were given as loans, rather than grants, setting the foundation for another debt crisis.

France also canceled a debt of $77 million, but this debt was unrelated to the debt that Haiti paid for its independence. According to The Africa Report, one of the greatest heists in history occurred in 1825 when King Charles X of France decreed that Haiti’s independence would only be recognized “at the price of 150 million francs,” an amount that was meant to compensate the French for any lost profit from slavery.

Although the amount was reduced to 60 million francs in 1838, the Haitian government had to take out loans multiple times to pay the balance. And according to “Haiti, France and the Independence Debt of 1825,” by Anthony Phillips, 80% of the government’s revenue went to Haiti’s debt as late as 1915. As a result, healthcare, education, and infrastructure funding were practically nonexistent throughout the 19th century.

Haiti continued to pay its independence debt until 1947, 122 years after independence, and researchers agree that the drain of the independence debt is directly responsible for the underfunded public resources in the country.

Disastrous aid

Although billions of dollars were seemingly raised, a fraction actually made it to the Haitian population. When the Nonprofit Disaster Accountability Project tried to conduct a report on the transparency of NGOs in Haiti, only eight out of 196 organizations had readily available information about their work. And of the roughly 40 organizations who responded to the report, they claimed that they spent roughly $730 million on relief efforts despite receiving more than $1.4 billion.

According to ProPublic, the Red Cross was one of the many organizations to misuse funds meant for earthquake relief. Although the Red Cross raised nearly half-a-billion dollars and claimed to have built homes for over 100,000 people, in reality they only built six permanent homes in all of Haiti. They also refused to disclose information about how they spent the hundreds of millions of dollars, and “will not provide a list of specific programs it ran, how much they cost or what their expenses were” (via NPR). Ultimately, most of the money never reached those who needed it.

It’s also impossible to know which projects failed and which ones succeeded. But it’s estimated that out of $6 billion dollars in aid, less than 10% went to the Haitian government and “less than 0.6% went directly to Haitian NGOs and businesses.” Meanwhile, as of 2020, over 300,000 people remain in tent cities as a result of the earthquake, and many more still don’t have reliable paved roads, clean water, or electricity.

NGOs in Haiti

Roughly 4,000 NGOs are registered in Haiti, but there’s no oversight over their aid or even the efficacy of the aid. And the number of missionaries in Haiti is completely unknown. According to The Guardian, Haiti has “more NGOs per square mile than any other country.”

In 2004, the United States instigated a coup to overthrow President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who had been democratically elected, and the coup was supported by numerous NGOs. And during the attempted reconstruction after the earthquake, NGOs repeatedly kept Haitian people out of the decision-making process, while bringing in their own amateurs.

It’s estimated that out of every $100 spent on Haiti’s reconstruction projects after the earthquake, “$98.40 returned to American companies.” According to “Disastrous Aid in Haiti Before and After the Earthquake,” by SarahAnne Perel and Madeline Halpert, out of the $200 million given by USAID for construction and relief contracts, after a year “only 2.5% of the money had gone to local companies.” Often looking only to help themselves, in doing so NGOs also end up wasting a great deal of the money, sometimes paying five times more to foreign contractors than what it would’ve cost with a local contractor.

Political dysfunction in Haiti

After the earthquake, Haiti was wracked with political dysfunction as Haitians lost faith in their political leaders, reports National Geographic. And with multiple presidential and legislative elections between 2010 and 2020, the people repeatedly tried and were unable to get their bearings.

According to Jubilee Debt Campaign, part of this dysfunction may have arose as a result of the United States’ interference in the 2010 election, “effectively banning one party, preventing Aristide’s return and influencing the vote counting process.” And according to the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, both the United States and the European Union had little concern about low voter turnout and fraud.

The election in 2016 also had a “record low participation of 17.3%,” and President Jovenel Moïse, who came to power in 2016 as a result, encouraged the Haitian Army and marginalized small-scale farmers. Since 2018, waves of protests have erupted across Haiti calling for the resignation of President Jovenel Moïse. In September 2020, Port-au-Prince was also brought to a standstill by police who were protesting the ruling class.

A countrywide lockdown known as Peyi Lòk occurred in 2019, lasting almost three months as anti-government protestors shut down streets to prevent movement around the capitol. Most of the discontent was fueled by the embezzlement of at least $2 billion in aid that was meant to be invested in post-earthquake projects and in the government’s lack of accountability.

Still recovering a decade later

Since many of the NGOs that arrived in Haiti after the earthquake came to serve their own interests, with little-to-no coordination between them, and with unstable and corrupt governments, for many Haitians things have only “gotten worse” in the ten years since the earthquake.

Although the cholera crisis was reigned in after ten years, according to the Centre for Humanitarian Action, it’s estimated that over 4 million people in Haiti are still affected by food insecurity. At minimum, 30,000 people remain displaced, living in tent cities that turned into permanent settlements with no power.

According to National Geographic, both the presidential palace and the cathedral remain in ruins and still haven’t been rebuilt, and a public hospital that was promised by France and the United States “remains an empty shell, the work temporarily halted due to a dispute over money.” And, despite the existence of earthquake monitors, no one monitors the equipment overnight because the building where the equipment is kept isn’t earthquake proof, and the shift is unpaid.

In October 2019, the government also failed to hold elections for parliament seats, and as a result President Jovenel Moïse has been ruling by decree since January 2020. In October 2020, Moïse also began pushing for constitutional reform. Despite the many protests against him, Moïse is refusing to give up power, and with the COVID pandemic, Haiti is at risk of another humanitarian crisis.

The Truth About Saddam Hussein's Forbidden Blood Qur'an

The Archangel Uriel: The Untold Truth

The Tragic Story Of Chinese General Yuan Shikai

The Dark Truth About Radical Group Boko Haram

The Myth About Ostriches You Need Stop Believing

The Mystery Of Australia's Pink-Colored Lake Hillier

Son Of Sam: The True Details About David Berkowitz's Military Service

How This Charming Fruit Bat Is Easing Into Retirement

Ridiculous Ideas That Made Millions Of Dollars

What Really Ended Hulk Hogan's Wrestling Career