Famous People Who May Never Have Existed

In our present age of choking, overpowering, ubiquitous information, it’s easy to search for the biography of a celebrity or politician because history is better preserved now than ever before. Everything you never wanted to know about Britney Spears’ hairstyle history, for example, you can find out. And then you can never forget it.

Alas, it was not always this way. The facts about many historical famous people weren’t written down until years — sometimes decades or even centuries — after they allegedly lived. Given this amount of time, the evidence of the person’s existence itself may have completely deteriorated, and the legends themselves might have borne little resemblance to what actually happened. But we’re habitual creatures who like good stories, so we just keep on telling the same ones, facts be damned. Here are some famous people whose names you will recognize but who may never have existed at all, at least in their popular form.

Mulan

When Disney introduced Western children to the legend of Mulan, she was already a big deal in Chinese literature. The tale of a warrior’s daughter dressing as a man and fighting in her ailing father’s place is a timeless bit of badassery and girl power. But the evidence of her existence is scarce to say the least.

A book about women in Chinese history mentions Mulan might’ve been a made-up figure partly based on Wei Huahu, an actual female warrior from ancient China. It’s unknown, however, if Huahu ever fought in men’s clothing. As for Mulan herself, the earliest known reference to her was in the ancient ballad “The Battle of Mulan.” But the song doesn’t specify when she lived, gives few details of the actual battles she fought, and didn’t give a full name for her outside of “Mulan.” Pretty vague!

Then there’s a text (translated as Exemplary Women of Early China) written by Liu Xiang around 18 BC, and packed with over 120 biographies of famous women from ancient China. Mulan, despite supposedly being a major deal, has no biography. Granted, she supposedly lived several hundred years after Xiang first published his book, but there’s a section at the end for “supplemental biographies.” No one has ever added Mulan, even though what she did was quite exemplary indeed.

William Shakespeare

Surely the great William Shakespeare was real, right? He has writings — lots of them — and we have portraits of the man. How could he be phony? Amazingly, quite easily. Many people are convinced “William Shakespeare” was a pen name, and whoever wrote those stories might be lost to history.

As recapped by PBS, there was a guy named William Shakespeare, but we know little about him. We don’t know where he learned to write, and his will mentions no plays or sonnets. Maybe the real Shakespeare didn’t write much more than a grocery list. If so, it’s unclear who the “real” Shakespeare is. Plenty of candidates have emerged over the years — like Francis Bacon, Ben Johnson, and Christopher Marlowe — but these possibilities haven’t stuck.

There’s another legitimate possibility in the obscure Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere. According to J. Thomas Looney, a schoolteacher who uncovered a great deal about the man, Vere wrote poetry that reads much like what the Bard wrote. According to this theory, Vere used an assumed name because, as nobility, he didn’t want to be associated with a low-brow art like playwriting. Then, when he died, his followers published his plays under the pen name of some random, dead commoner named William Shakespeare.

Robin Hood

The legendary English folk hero Robin Hood is well-known for robbing from the rich and giving to the poor, residing in Sherwood Forest with his gang of outlaws, and wooing Maid Marian. The stories are certainly fictitious, but was Robin Hood a real person or simply based on one? It’s impossible to say if any one individual inspired the legend’s creation. The stories are either totally invented, or are a combination of elements taken from different historical sources.

Identifying a single person as the basis for the famous outlaw becomes even more difficult given that, as the stories began to grow in popularity in the 13th and 14th centuries, random English outlaws began to call themselves Robin Hood. Nevertheless, some historians speculate that Robin Hood was based, in part anyway, on nobleman Fulk FitzWarin, who rebelled against King John (one of Robin Hood’s foes). FitzWarin’s life was later turned into its own medieval tale, Fouke le Fitz Waryn, which holds some similarities to the Robin Hood stories. If he was the basis, then a name change was a good decision. The name Fulk FitzWarin doesn’t exactly strike fear into the hearts of villains.

Confucius

To quote Confucius: “If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.” That’s deep … and deeply problematic. Research suggests that dishonest children become successful adults and that highly successful adults lie. That’s a whole lot of wrong there, Confucius.

Of course, if Confucius never existed, then the quote’s been misattributed, meaning the words can’t accord with the truth. Thus, in being wrong, the quote would be right, which sounds super wrong. And the Confucian confusion doesn’t end there. Experts believe he was born in Lu, China, and created the Ru School of Chinese thought. But depending on which document you read, Confucius comes off as an unflinching idealist, an ambitious politician, or a fifth-century B.C. superhero. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy cautioned that even The Analects, the go-to resource on Confucius, suffers from striking inconsistencies and improbabilities.

In fact, many claims attributed to Confucius are arguably apocryphal. Fittingly, the guy described as China’s Socrates raises more questions than he answers.

William Tell

William Tell is a Swiss folk hero best known for child endangerment. Tell allegedly lived in Switzerland during the early 14th century, when the Hapsburg dynasty of Austria ruled the land. As the story goes, an Austrian official placed a hat on a pole in city of Altdorf and commanded every Swiss subject to remove their caps as they passed by it. One day, Tell, a local peasant who was accompanied by his son, refused to do so. In response, the Austrians forced Tell to shoot an apple off his son’s head at 120 paces or face execution. Tell loaded his crossbow and skillfully shot the apple. He then went on to lead a small revolt against the Austrians — presumably after buying his son some new pants.

Tell is essentially the Swiss version of Robin Hood and, much like the outlaw of Sherwood Forest, he probably never existed. The apple story is extremely similar to a Viking folktale, which most likely was imported to Switzerland at some point and used by Swiss patriots as a rallying cry against their Austrian rulers.

Sun Tzu

Sun Tzu’s The Art of War has long been revered as the preeminent guidebook on how to properly wage war. So who better to advise than someone like Tzu, an ancient Chinese military leader and warrior who knew how to fight and win? He also knew how to motivate his charges, reportedly beheading two men popular with the king, just to show the other courtesans nobody was safe from punishment and discipline.

But now, people wonder if Sun Tzu was real at all. As History explains, scholars currently know nothing about where The Art of War came from, only that it would randomly appear — usually on sewn-together bamboo slabs — for whatever military person or scholar needed it. There’s no record of “Sun Tzu” promoting himself as the author, and even the story of him beheading those poor courtesans is unsourced and quite possibly a myth.

It stands to reason “Sun Tzu” is a pen name, and Art of War’s contents are cobbled together from generations of Chinese military lessons, theories, and strategies. Considering how people worldwide are still reading and learning from it, thousands of years after it first appeared, it’s clearly solid advice. It just probably didn’t come from the mind of one cruel military genius.

Sybil Ludington

Sybil Ludington is remembered for having been forgotten, an unsung heroine from the Revolutionary War eclipsed by a lesser contemporary. Known by many as the female Paul Revere, Ludington legendarily rode 40 miles alone in the rain over difficult terrain to warn New York Yankees that the British were coming for more than crumpets. At just 16 years old, she braved the dangers of tea-swilling troops and lurking lawbreakers, sounding the alarm from Putnam County to Dutchess County in New York’s Hudson Valley. And it was 1777, so there was no 7-Eleven to save her from a snack attack.

According to that account, history should laud Ludington more than Revere because she traveled double the distance he did under dismal conditions. But tell that to history and it might call you a filthy liar due to lack of reliable sources. As per Smithsonian Magazine, the first mention of Ludington’s ride didn’t appear until 1880, more than a century after it supposedly happened. That’s no small oversight, considering that women of the age (understandably) wanted to vaunt their own contributions to American independence.

Nowadays, Ludington’s face features on stamps and in coloring books. She has become a mascot for feminists and anti-Communists as well as a bogey-woman for certain political factions. She’s as real or fake as people need her to be to make a point, much like history itself.

Homer

Homer is the Greek poet who wrote two of the books that your English teacher forced you to read in high school — the mythological epics The Iliad and The Odyssey. Despite the popularity and importance of these epics, their author remains shrouded in mystery. For one thing, Homer almost certainly wasn’t the originator of these tales, which likely preceded him by about 1,000 years. He was simply the first to write them down. As for the poet himself, some say Homer was blind, while at least one author argues that Homer was actually a woman.

Some historians believe that Homer was not a single person, but rather a group of Greek scholars. In the end, we will probably never know the answer, but the legacy of Homer’s works will continue, both in the nuclear plant and beyond.

King Arthur

Unless you’ve been living under a rock — a heavy one — you’re probably familiar with the Arthurian legend. Even if you haven’t read the stories, you likely saw Monty Python and the Holy Grail at least once in college, or maybe you heard the bad reviews about the 2017 King Arthur movie, pictured above. In any case, the British king is said to have claimed the sword, Excalibur, from the Lady of the Lake and found the aforementioned Cup of Christ. These fantastical stories are clearly a mishmash of folklore, but was the Arthur of legend based on a real man? The first tales of Arthur appeared in the ninth century and chronicle his battle against the invading Saxon armies, so it’s likely that the individuals — if they existed — who served as the basis for Arthur lived sometime before then.

Some historians suggest the Roman military commander Lucius Artorius Castus as a possible candidate. The King Arthur movie from 2004, starring Clive Owen, follows this line of reasoning and depicts him as a Roman soldier. Others suggest Riothamus, king of the Britons during the fifth century. In any case, we’re reasonably confident that the historical Arthur — whoever he was — didn’t have easy access to two hollowed-out coconuts.

Mary Magdalene

For seemingly forever, much of mankind has celebrated three major Marys: the Virgin, the Poppins, and the Magdalene. The first birthed a divine baby. The second brandished a magical umbrella. And the third knew men biblically for pay. Or did she? Most people know Mary Magdalene as the penitent prostitute who came to Jesus and atoned for her fleshly indiscretions. But as the BBC observed, there is zero scriptural justification for that belief.

The Bible never described Magdalene as a sinner, let alone a play-for-pay pal. As far as the Good Book is concerned, she was a good woman who did Christ a solid by washing his feet. Plus, she saw his resurrection, which sounds pretty important. The Independent, on the other hand, raised a more radical possibility: that Magdalene married Jesus. A 1,500-year-old text called “The Lost Gospel” claimed that Jesus and his favorite foot-cleanser actually became Mr. and Mrs. Christ and had a kid together. In this alternate history, the Virgin Mary is Mary Magdalene and not Jesus’ mom.

So how did the apparent mix-up happen? The BBC posited that Magdalene got conflated with a different biblical Mary (the sister of Martha) and an unnamed prostitute. Smithsonian Magazine similarly postulated that the Bible’s five different Marys and three carnally wayward women (who are all nameless) caused confusion. Mary Poppins thankfully doesn’t have that problem.

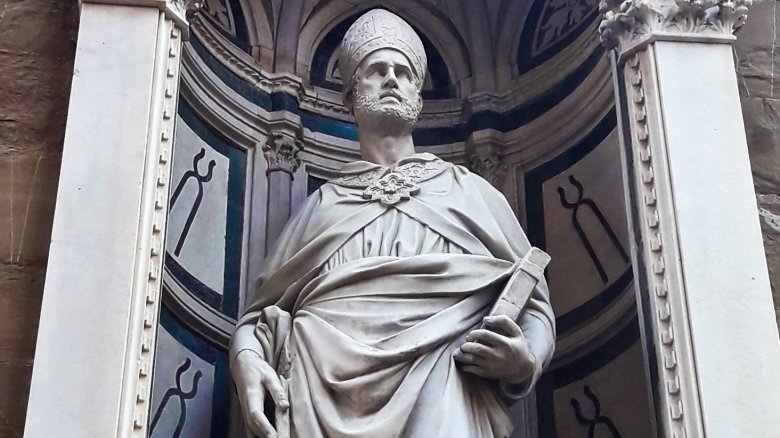

Pope Joan

Pope Joan supposedly became pope in 855 AD, a time when most women weren’t allowed to do anything at all. But then, two years later, she got pregnant and was either murdered or banished that day, depending on the storyteller. It’s an amazing tale, both from a feminist and historical perspective.

Except that may be all it is: a tale. According to ABC News, there’s lots of debate about whether Pope Joan ever existed. Believers point to hundreds of documents detailing her life, and Renaissance poet Giovanni Boccaccio placing her #51 in his book 100 Famous Women. Plus, St. Peter’s Square sports carvings of a woman wearing a papal crown while giving birth. That sounds very Joan.

The Catholic Church’s official stance is that she’s an urban legend, and legitimate scholars back them up. Professor Valerie Hotchkiss, of Southern Methodist University, believes Joan’s story comes largely from a single book: History of Emperors and Popes, by a monk named Martin Polonus. However, Polonus might not have added Joan — somebody else possibly edited her in after his death. From there, other monks blindly added the story into their manuscripts, because it sounded good and they didn’t think enough to fact-check it. True or not, we can all agree it’s a great story.

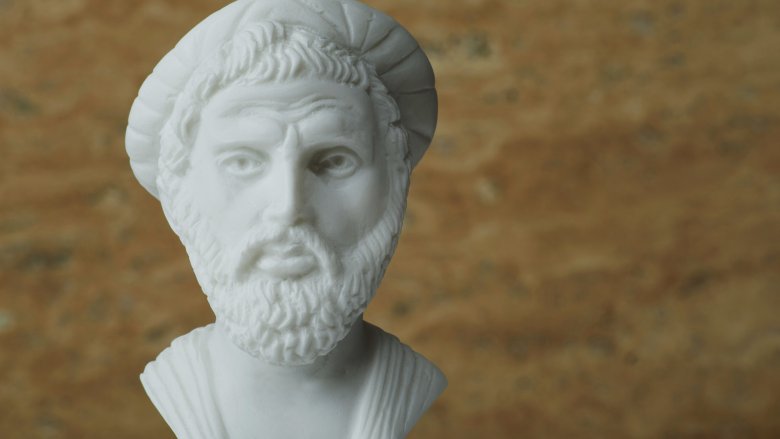

Pythagoras

Pythagoras’ influence on mathematics can’t be overstated, though high school students stumped by the Pythagorean Theorem might argue otherwise. But there’s a growing movement of people who don’t see Pythagoras as a mere bane of freshman geometry class — they see him as a work of fiction.

As explained in the bookClassical Philosophy: A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, Volume 1, Pythagoras never wrote anything that we know of. Everything we know about the man comes from outside sources like his followers, known as Pythagoreans (like Hulkamaniacs, only way dorkier). There’s even doubt that his mathematical breakthroughs came from him or his followers. As told by M.F. Burnyeat, he didn’t discover his own theorem, and celestial spheres weren’t seriously thought about until decades after he died.

Then there’s the Book Of Dead Philosophers, which states even classical scholars think Pythagoras is a made-up famous person. That’s because of his lack of writings and also an ancient Italian cult called Pythagoreans. They might well have invented Pythagoras as a figurehead “leader” to justify wacky, fanatical beliefs like “A-squared + B-squared = C-squared.” Also, that odd numbers are male and even ones are female. If Pythagoras was real, he was clearly an odd duck.

John Henry

John Henry has been immortalized in folk music since the 1800s. His “Ballad of John Henry” tells the story of an ex-slave working on the railroad who could wield a hammer with the best of them. He challenged a steam drill to see who could work faster, and he won, though he soon died from sheer exhaustion. The greatest heroes die in the end, and Henry’s story has ascended to near-myth because of it.

Thing is, though, he might actually be a myth. As NPR explains, John Henry is almost certainly a “tall tale,” though one based on “historical circumstance.” There were obviously men working on railroads back in the 1800s, and steam drills were eventually introduced as a way to speed up labor and reduce costs. More than likely, the rail workers disapproved of a machine taking their jobs, so the idea of outworking a machine was an inviting one.

St. Christopher

St. Christopher is one of those jack-of-all-trades saints. He’s the patron saint of travelers and fruit dealers. Followers adore him, and his talisman is a popular item among believers and tourists alike. There’s just one issue: He may not have been a real saint, or even a real person.

As explained by the LA Times, many scholars are convinced he wasn’t real. At the least, they feel that were he real, everything saintly about him is based on pure myth. Instead of someone who accepted Christ and converted 40,000 pagans to Christianity before being martyred, he might have been just a regular guy who, after being captured by the Romans and drafted into their military, converted to Christianity and was murdered for it. Those from the local church called him Christopher since they didn’t know his real name, and Christopher meant “bearer of Christ” so it worked.

The issue of his existence is so controversial that, in 1969, the Vatican “kicked [him] off the universal calendar,” meaning his feast day was no longer required, and you only had to venerate him if you really wanted to. But he was never de-sanctified because, according to Professor David Woods of University College Cork, Christopher “has a genuine historical core.” We may never know.

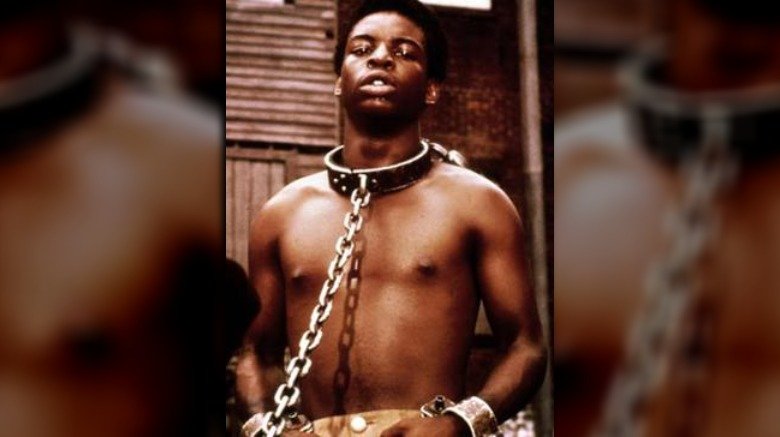

Kunta Kinte

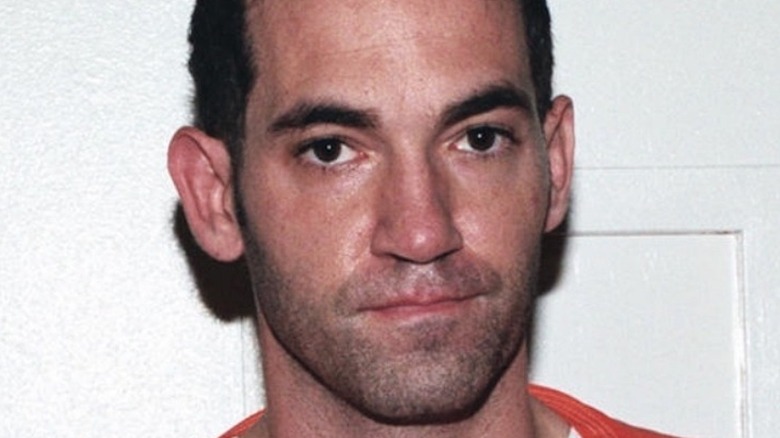

In his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Roots, Alex Haley poignantly wrote: “In all of us there is a hunger, marrow deep, to know our heritage.” His own ancestral hunger led him to Juffureh, Gambia, where his great-great-great-great grandfather Kunta Kinte (depicted above) was purportedly born. Per Haley’s own description, Kinte lost his freedom in 1767 when he was enslaved by British captors. Bondage didn’t break his spirit, however. After arriving in America, Kinte repeatedly defied his oppressors, escaping multiple times.

About 200 years after Kinte’s kidnapping, the TV miniseries Roots became an instant classic. According to CNN, the broadcast marked a watershed moment in American perceptions of slavery. It also deeply impacted Gambia, where an island was named after Kinte and his birthplace became a tourist attraction. These are effects are real, but there’s a really strong chance that Kinte isn’t.

You might already know that Haley’s Roots had a strained relationship with the truth and got pretty chummy with plagiarism, but it’s worse than you might think. As the Washington Post reported, journalist Mark Ottoway ripped Roots’ avowed historicity to shreds, dismissing Kinte’s backstory as highly implausible. Haley’s single source of information was a demonstrably unreliable villager. And at the time Kinte was supposedly enslaved, his village was already a British trading post where Gambians worked alongside, not against, slavers. Unless Haley’s chronology was way off, a real-life Kinte would have likely remained free. Whatever Haley hungered for, it wasn’t accuracy.

Lycurgus

Lycurgus is famous as the lawgiver who shaped much of ancient Sparta’s legal policy. Someone had to come up with these laws, so why not Lycurgus, a guy well-versed in doing so? Well, maybe Lycurgus was just a mascot.

According to Britannica, several writers and historians from the fourth century BC and prior wrote of Lycurgus, though rarely did they agree on specifics. Herodotus, for example, wrote that his policies were shaped by what Crete did. He also said Lycurgus belonged to the Agiad house, one of two Spartan houses that controlled the nation’s royalty. Meanwhile, a historian named Xenophon believed his ideas came from the Dorians after they invaded Laconia and turned the Achaean people there into serfs. By Xenophon’s time, many people believed Lycurgus was part of Sparta’s other ruling house, Eurypontid, and was king regent there. Basically, his origin story is more muddled than Wolverine’s.

It gets even more confusing because some scholars believe a guy named Lycurgus really existed and really played a role in introducing sweeping reform to quell a major serf revolt in the seventh century BC. But the famous Lycurgus who basically shaped Spartan law by himself, many believe, wasn’t real, he was just used as a catch-all figure for ancient Greeks to name-check when discussing politics, as they were apparently wont to do. It’s certainly easier than rattling off the many hundreds of names who played an actual role.

Lao Dan

The founder of Taoism, ancient Chinese philosopher Lao “Laozi” Dan is a revered figure indeed. Those who do so, however, may be looking up to a made-up master.

According to GB Times, there’s a ton of confusion regarding Lao Dan, including his name. Some believe Lao Dan was his real name, while others think scholar Sima Qian — among the first to write of Dan — confused stories he heard about Laozi with that of another philosopher, Li Er. According to this theory, he mistakenly combined the names to come up with Laozi, or Lao Dan. But Laozi was also a term of respect for Laoist teachers, complicating the matter even further.

Then there’s his writings. Supposedly, Dan wrote the Tao Te Ching, but reading it’s like reading the same book by several different authors. There are many shifts in tone, style, and content, and we currently have little proof the book’s language was even used when the book was supposedly published. Likely, then, Laozi’s writings were written long after Lao Dan supposedly lived and died, and probably several people cobbled “his” life-affirming teachings together into one semi-coherent package. It’s like if all the stories in Chicken Soup For The Soul were credited to one guy named Bill.

How Rabbits Once Nearly Assassinated Napoleon

The Truth About A Feral Child Who Was Kept As A Royal Pet

The Reason Some Are Convinced Kurt Cobain Is Still Alive

This Is Where You'll Find The Remains Of Pringles Designer Fredric Baur

Newly Discovered Brain Signal May Explain What Makes Us 'Human'

82-Year Old Female Bodybuilder 'Clobbers' Home Intruder

Here's How Much A Miniature Cow Will Cost You

What Is The Longest Tapeworm Ever Recorded?

How Much Money Does Mark Zuckerberg Make Per Hour?

Who Owns The Moon?