Here’s What It Was Like For Prisoners In Ancient Rome

To most, prison is a living hell. But in many cases, the conditions were much worse in the distant past. The ancient Romans were known for their brutality on the battlefield, and their treatment of prisoners was no different. Fortunately, for the majority of those imprisoned, confinement was often brief because even the Romans thought life imprisonment was inhumane.

But for the few not-so-lucky long-term prisoners, circumstances were horrendous, from dark caves to severely claustrophobic cells. Some prisoners were thrown into subterranean pits nearly devoid of light, which make modern-day prisons look like being locked up in a cheap motel room by comparison. Rome’s most infamous prison is an underground dungeon about 12-feet down, and it may have been the origin of the phrase “to be cast into prison.”

In general, prison sentences were short, and for the wealthy they were largely nonexistent. Blessed with prestige, the rich often faced house arrest or banishment instead of imprisonment. The poor also often avoided long confinement, but usually because they were sentenced to death instead. Here’s what it was like for prisoners in ancient Rome.

Prisoners were temporarily confined until punishment

Especially in early Roman history, prisons as we know them today did not exist. Instead, prisoners were kept in holding cells until their trial or punishment, according to UNRV. Execution was a common punishment, especially for the lower classes, and it was often carried out in a very brutal manner. Criminals convicted of less serious crimes may have had to pay a fine as a penalty, or could have been forced to serve as slave labor.

Later in the imperial age, imprisonment became more common, though this was initially an unintentional result of overcrowding before trials. Roman officials, law experts, and even emperors condemned the imprisonment as inhumane, including the third-century jurist Ulpian, who wrote “prison indeed ought to be employed for confining men, not for punishing them.”

In the reign of Hadrian, provincial governors were forbidden from confining anyone for life, regardless of the crime. Further, Emperor Antoninus must have despised the idea of imprisonment because he said, “your statement that a free man has been condemned to imprisonment in chains for life is incredible, for this penalty can scarcely be imposed [even] upon a person of servile condition.”

The barbaric punishments of the early Romans

The first written Roman law code, known as the Twelve Tables, was issued in 451 B.C. It lists several serious offenses and the harsh consequences for those convicted, according to Edward M. Peters in “Prison before the Prison.” Condemned prisoners faced all sorts of horrific capital punishments, sometimes very similar to the crime itself, such as the burning of arsonists. Other gruesome punishments included decapitation, hanging, clubbing to death, or being thrown off of the Tarpeian Rock, a steep cliff. There was also a law specifically for the Vestal Virgins, priestesses of the Roman goddess of the hearth, Vesta. If they did not remain chaste, they received the horrific fate of being buried alive.

By far, the strangest and most terrifying early punishment was the culleus, a nightmarishly creative punishment for the murderers of close relatives. The convicted person was placed in a sack with an ape, a dog, and a serpent. The sack was then sealed and tossed into the sea.

House arrest or voluntary exile for the wealthy

While conditions were often brutal for the poorest Romans convicted of a crime, the wealthiest citizens were rarely imprisoned. Instead, they were often put under house arrest while they awaited trial. Plus, voluntary exile was a much more available option to prominent aristocrats. It might sound like an obvious choice to take exile over execution, but exile came with its own dangers and hardships — even the most powerful lost their citizenship and all immovable wealth. Even worse, if they made the idiotic decision to return to Rome, any citizen was free to murder them on sight.

By the first century A.D., two main types of exile for upper class citizens had been established, according to Fergus Millar in “Condemnation to Hard Labour in the Roman Empire, from the Julio-Claudians to Constantine.” While during the Republic, wealthy Romans were only forced to stay away from certain places — most often the city of Rome and its surroundings — a newer, harsher form of exile later emerged. Deportatio forced citizens to live in a specific, undesirable location. It was the worst punishment for the rich in the early imperial age, unless the crime was particularly vile, such as arson, treason, or murdering a parent or relative.

The power of the paterfamilias to imprison family members

The male heads of Roman households, known as the paterfamilias, had unlimited power over the entire family, which even included the right to imprison family members as a punishment. Cells inside homes were called ergastulum, and they could be the size of a closest for individual punishment, or large roofed pits where several people could be imprisoned at once, according to Invicta. Forced confinement was most often used by paterfamilias to punish slaves, so villas often had designated areas for slaves to be shackled, as well as places where they were held but given a little more freedom, and areas for well-behaved slaves.

It was fully within the father’s rights to imprison any family member to maintain discipline, no matter how minor the misbehavior was. This meant that, hypothetically, an elderly, noble father even had the power to punish his established, senator son.

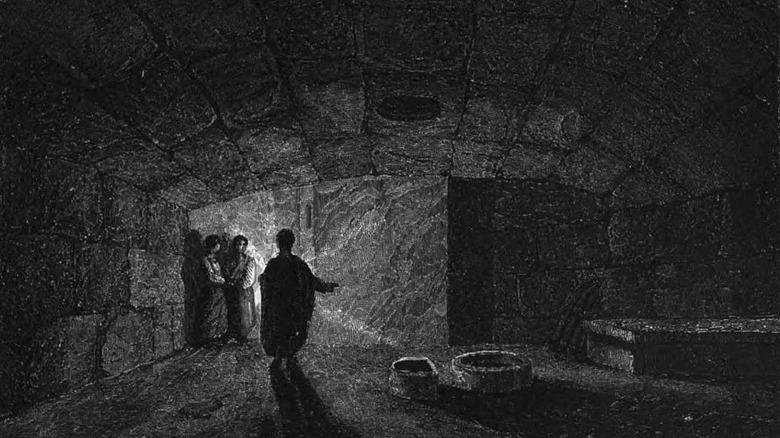

The Mamertine Prison

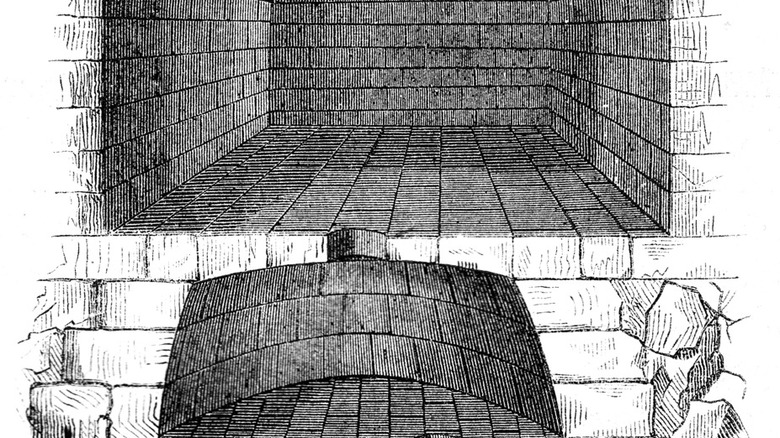

The Romans’ first prison was also its most notorious, with an ancient history stretching back to the fourth king of the city. According to UNRV, in the seventh century B.C., Ancus Marcius began the construction of a subterranean structure at the foot of the Capitoline Hill and next to the Forum Romanum. According to Atlas Obscura, the site was originally a cistern for a spring underneath the floor before it was converted into the infamous prison cell.

The small, horrifying dungeon served as either an execution chamber or a place where prisoners were confined and left to die of starvation. The sixth king, Servius Tullius, covered up the dungeon except for a tiny hole for an entrance, making the prison even more dark and terrifying. The nearly pitch-black chamber is 22-feet wide, 30-feet long, with walls only 6.5-feet high, and located more than 12-feet underground. By the third century B.C., the prison was known as the Tullianum. The Roman historian Sallust described the dungeon as “disgusting and vile by reason of the filth, the darkness and the stench.” (via UNRV).

In the late second century B.C., a far less ghastly, trapezoidal cell was added above the Tullianum to give some prisoners slightly better conditions during their confinement, including light from a small window. By the Middle Ages, the entire complex was known as the Mamertine Prison, a name most likely derived from the nearby temple of Mars Ultor.

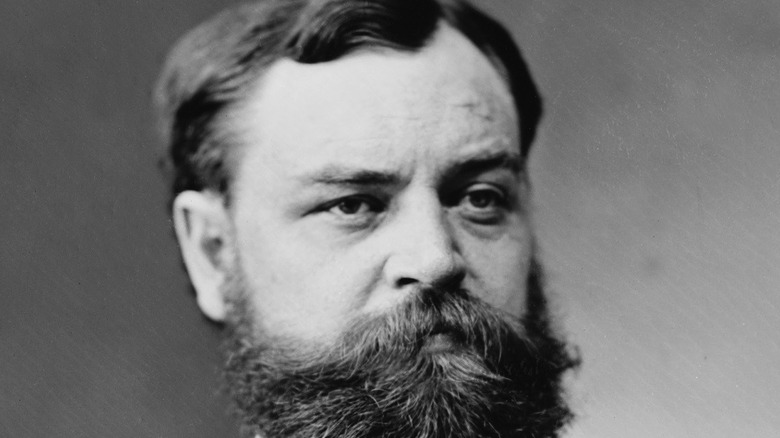

High-profile prisoners of Rome

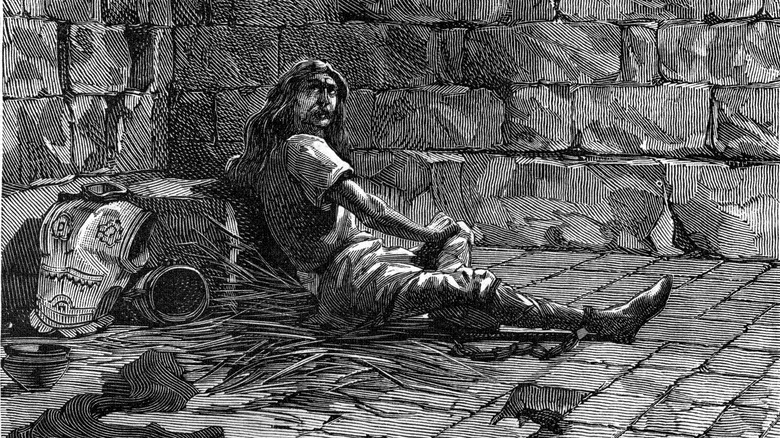

Many people, both citizens and foreigners, endured the horrid conditions of the Mamertine Prison over the centuries, including several famous men who defied Rome. According to Encyclopaedia Romana, these prisoners include Jugurtha, the king of Numidia, who was starved to death within the Tullianum; Vercingetorix, the rebel leader of the Gauls, who fought Caesar before he was executed; Simon Bar Jioras, the commander, who defended Jerusalem; and the martyr St. Paul. Many captured kings and foreign leaders faced the ultimate humiliation of being paraded through the city in triumph before they were lowered down into the subterranean dungeon.

Important Romans were also imprisoned within the Mamertine Prison during the Republic and the empire, including Lentulus and his co-conspirators with Catiline in 63 B.C. and Emperor Tiberius’ praetorian prefect, Sejanus, in 31 A.D. UNRV reports that it is said that the corpses of prisoners from the Tullianum were tossed through an iron door into the main sewer of Rome.

Private prisons run by debt collectors

In addition to household cells and the often-brief confinement prisoners endured before execution, there was another kind of Roman prison — those owned and operated by private creditors. Known as carcer privatus, these private prisons were used to hold citizens who failed or refused to pay their debt. In fact, imprisonment is only mentioned in the Twelve Tables when referring to laws about debt, according to Edward M. Peters.

Debtors could be imprisoned for up to 60 days if they were unable or unwilling to pay off their debt. Then, after their debt was announced publicly three market days in a row and the situation remained the same, debtors were either sold into slavery outside Rome or executed. The wealthy took advantage of these private prisons during the first century B.C., when Rome was fraught with civil war and instability. The rich targeted poverty-stricken farmers, or even innocent travelers, and forced them to labor on their massive lands and estates.

The Roman magistrates with the power to imprison citizens

Minor magistrates called tresviri capitales served as an early type of police force in ancient Roman society. These officials had the authority to temporarily imprison citizens for disobeying their commands, or for public disorder. Along with the famous playwright Naevius the satirist, the tresviri capitales are known to have imprisoned a man named C. Cornelius after he was convicted of abusing a young boy. These two prisoners were probably confined within the Mamertine Prison.

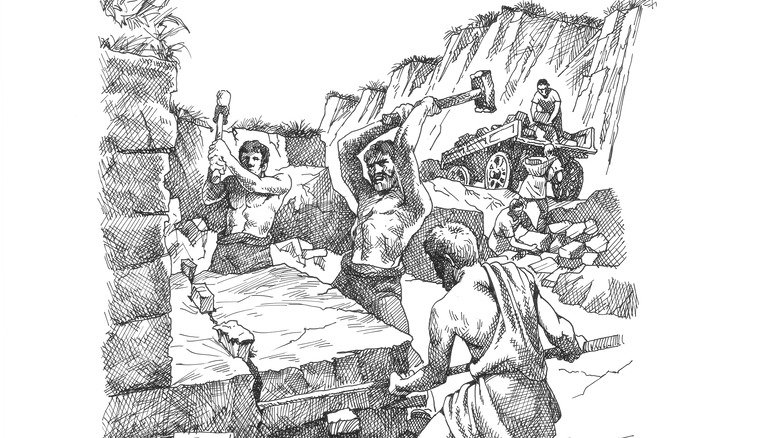

There was also another option more suitable to imprison larger groups of people. By the second century B.C., a former quarry located at the Capitoline Hill was converted into prisons called lautumiae, which were often used to hold prisoners of war but also confined some citizens. According to T. J. Cadoux in “The Roman Carcer and Its Adjuncts,” the carved-out caves of the lautumiae held large amounts of less-important prisoners, who were overseen by a few guards. It was not considered a big deal if a few prisoners managed to escape from the quarry caves.

Conditions in the lautumiae were certainly not ideal, yet they were better than the Tullianum since prisoners were usually fed and not just left to die. But even so, some prisoners were forced to resort to cannibalism to survive.

Prisoners of the provincial governors

There were also prisons outside of Rome, including one at Alba Fucens in central Italy. The captured king of Macedonia, Perseus, nearly died from the terrible conditions here in the early second century B.C. According to author David J. Rothman, the historian Diodorus Siculus described the prison at Alba Fucens as an underground cell only the size of a dining room meant for nine people, but often having far more crammed in. Siculus says that the experience turned the prisoners into brutes “since their food and everything pertaining to their other needs was all so foully commingled, a stench so terrible assailed anyone who drew near it that it could scarcely be endured.”

Perseus was not set to be executed. Instead, the Roman guards provided him with a noose and a sword, hoping he would choose to commit suicide. After he refused to take his own life, the king was removed from the gruesome environment. Perseus then survived two years in a slightly better prison until his guards murdered him by depriving him of sleep. Not much else is known about prisons outside of Rome, except that Hadrian specifically prohibited provincial governors from issuing life sentences.

More and more court cases increased holding cells throughout the empire

While Julius Caesar and Augustus ruled over Rome, the ever-expanding city replaced the latumiae with new buildings, says T. J. Cadoux. As Roman society became more sophisticated and the legal system evolved, more citizens went to court and needed to be contained before their cases were addressed, so more prisons were built to hold them. By the second century A.D., the increasing number of prisons in Rome led the satirist Juvenal to write about how he longed for the good old days when the city only needed one prison.

But even though there were more prisons, the legal system simply could not keep up with the number of cases. So, prisoners were confined for longer periods than was intended, especially among the poor. To deal with the issue, the Romans passed laws like limiting the amount of time that a person could be imprisoned to one year. Bail was also an option for those who could afford it. One exception to these rules were those labeled insane or mentally handicapped, who were often confined for life. When including both the public prisons and the private prisons run by creditors, along with prisons in the provinces, the overall number had grown considerably by the imperial age.

Owners of private prisons were imprisoned in the empire

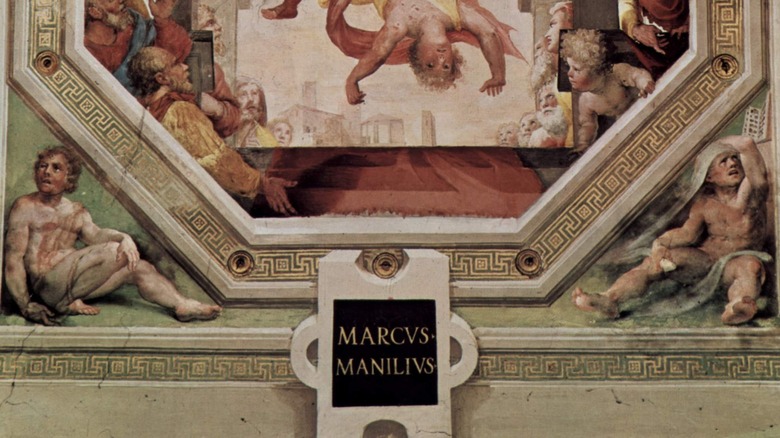

The demise of private prisons would not occur until the imperial age, but there were early signs that the people hated the practice. In 385 B.C., the war hero Marcus Manlius became even more popular when he tried to release a group of confined debtors. But the attempt failed, and Malius was imprisoned before being executed.

After the fall of the Republic, the emperors consolidated their power, and so private prisons were increasingly viewed as outside the law, says Invicta. In this new era, those who were caught running such prisons were imprisoned themselves in public prisons for as long as they had held others. If there had been many prisoners, the creditors had to be imprisoned for as long as they all were combined. Plus, all the debts they were owed from their captives were erased as well. But those were not the only consequences one could face — some creditors were tried and convicted of treason, which ultimately led to their execution.

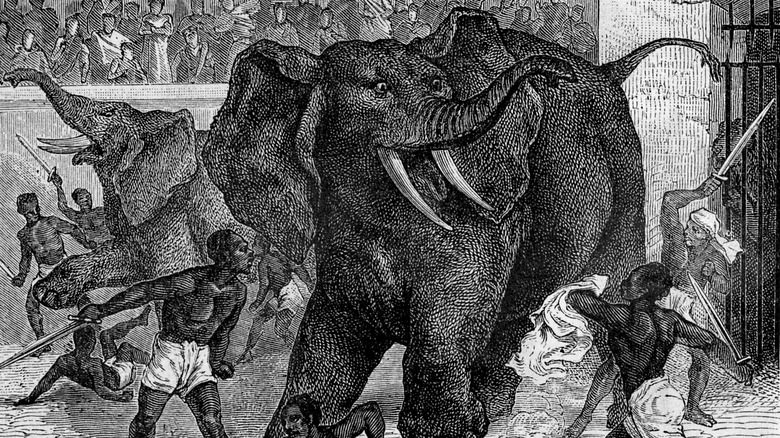

The “highest punishments” of imperial Rome

Both as a way to display their unlimited power and to deter crimes through horrific spectacles, the Roman emperors greatly increased the amount of the most brutal executions for the worst criminals — those guilty of crimes such as treason, murder, sexual assault, adultery, sorcery, and desecrating the dead. The executions were called summa supplicia, or the highest punishments, and included crucifixion, being thrown to the beasts, and being burned alive, according to Edward M. Peters. All of the executions were public events that were usually done in arenas, or at least in front of a crowd of onlookers.

The highest punishments were first used early in the imperial age, but reached an obscene level during the second and third centuries A.D. These later times were so bad that even the wealthy could be tortured or forced to endure the summa supplicia when found guilty.

Christian, traitor, and rebel prisoners of the Roman Empire

As the empire got larger, the overcrowded prisons not only had to deal with more criminal cases, but also with a growing number of Rome’s enemies, says Invicta. Rebels, traitors, and Christians were not only the ones who often received the highest punishments, but they usually endured harsh confinement and brutal torture since the prisoners were so despised by the state.

Imprisonment was not usually part of the official sentence, but some Christians, including one named Ptolemaeus, endured long periods of confinement before their official punishment. However, some Christians had a slightly better experience of imprisonment because they had regular visitors. In “The Oxford History of the Prison,” author David J. Rothman explains that “among Christians, the duty of visiting prisoners was recognized as soon as the persecutions began in earnest in the second century,” and that this was a result of Jesus’ prediction that those who visited prisoners would be counted among the righteous at the Last Judgment.

Prisons were regulated under Christian emperors

By the third century A.D., conditions in prisons had become so bad that later Christian emperors tried to reverse the trend and go back to at least some sense of civility when dealing with prisoners. From the reign of Constantine the Great and onwards, the worst parts of Roman criminal law were gradually removed until it was more similar to the laws of the early empire, as seen in the later law compendiums of the Code and the Digest of Justinian, according to Edward M. Peters.

As Christianity became more popular throughout the empire, it began to influence the way people saw prisoners and prisons. Early Christian views promoted charity and less severe punishments for fellow members of the church, but since the entire empire became Christian in the fourth century A.D., this concept became difficult to use as criminal policy.

How Lincoln's Son Was Linked To The Assassination Of Three US Presidents

Why Charles Lindbergh Was Once Given An Award By The Nazis

The Mysterious Disappearance Of Jennifer Dulos

The Deadly Cosmetic Trends Women Once Relied On

The Historical Cruelty Of Andrew Stoney And Mary Bowes' Marriage

The Truth About The Deadly Vaal Reefs Tragedy

The Most Infamous Crime Machine Gun Kelly Committed

The Tragic Story Of Britain's 1919 Race Riots

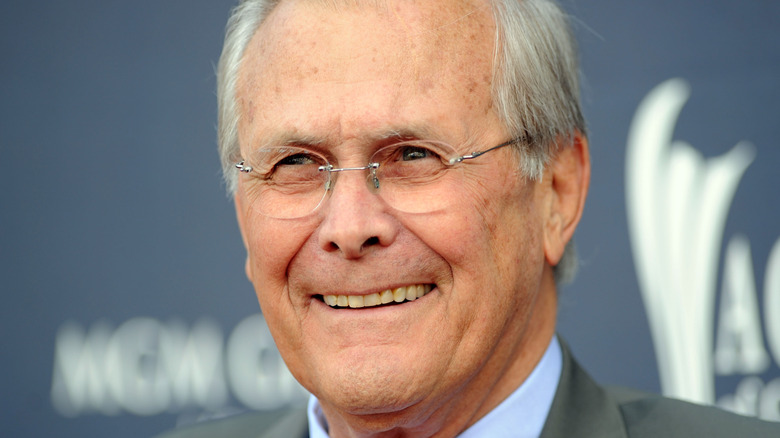

What Was Donald Rumsfeld's Net Worth When He Died?

The Real Reason The Rolling Stones Didn't Perform At Woodstock