The Civil War’s Biggest Blunders

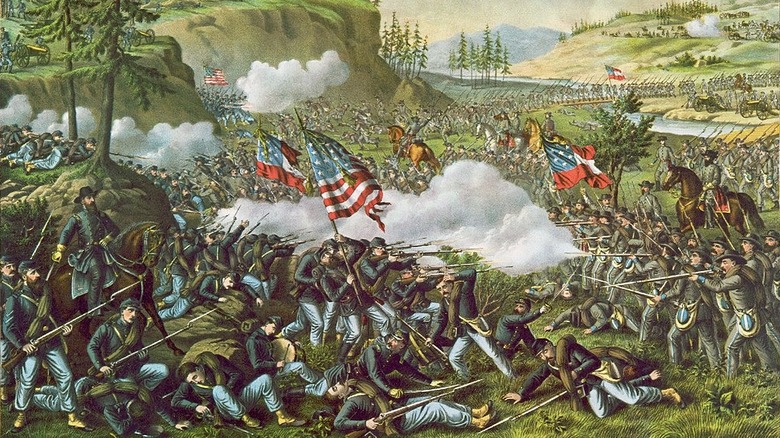

The U.S. Civil War pitted states against states and Americans against Americans. Over four years, U.S. and Confederate armies fought across the eastern half of North America, killing each other in bloody battles that would yield a butcher’s bill of nearly 600,000. As a result, the war holds the dubious title of America’s bloodiest.

Why the high casualties? One reason was that the Civil War was full of blunders by incompetent, vain, or brash generals and politicians, who influenced the progress of the war from Richmond and Washington D.C. The Civil War serves as a reminder that poor military decisions have consequences that are paid for with human life and blood. During the war, many men, whose names adorn numerous memorials and monuments throughout America, died from such decisions. Often, their deaths were unnecessary and in vain. Below are some (but definitely not all) of the worst blunders of the War between the States.

Fort Sumter, 1861: starting the war in the first place

The Civil War in and of itself can be accurately described as a Confederate blunder. The Mises Institute notes that it is unclear if Lincoln wanted a war, but his actions suggest that he may have hoped to bait the Confederates into starting one. Lincoln had been repeatedly advised to evacuate a federal installation in Charleston, South Carolina, called Fort Sumter, unless he wanted war. When U.S. ships attempted to resupply it, the Confederates took the bait, accusing Lincoln of conducting hostile operations in Confederate waters. Lincoln’s cabinet had also warned him that such a move would likely result in war, and Lincoln likely believed them yet went ahead with the resupply anyway.

On April 10, 1861, the Confederate government declared war on the United States. According to Tulane University, only Secretary of State Robert Toombs objected. With great foresight, he called the war a suicidal blunder that would doom the Confederacy and begged President Jefferson Davis to reconsider. The Confederacy could not be the aggressor in such a war. Such a posture would not win it any friends and would very likely unleash a “hornet’s nest” of hostility by much more numerous U.S. forces, per the Herald Bulletin. The South could never hope to win against this.

Despite Toombs’ correct observations, the war hawks won out. On April 12, 1861, Confederate guns under General Pierre Gustave Toussaint Beauregard shelled Sumter until it surrendered the next day. The Civil War had officially begun, and the Confederacy’s fate had been sealed.

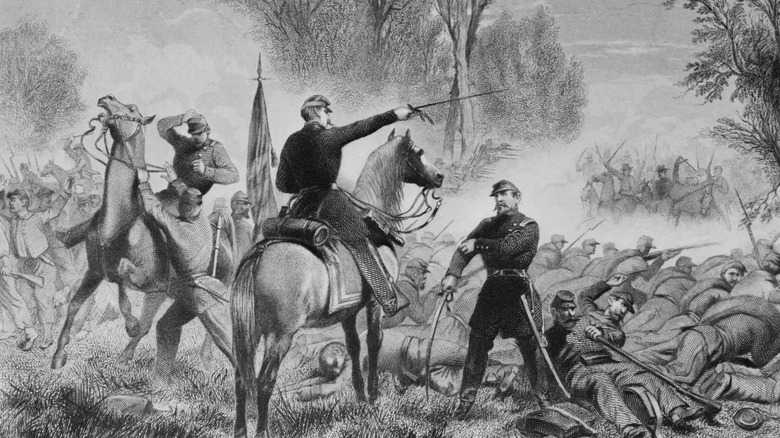

First Battle of Bull Run, 1861: Politicians set up defeat

Ohio History Connection notes that when the Civil War began in 1861, both sides expected a short, quick war. They quickly mustered up volunteer armies, setting the stage for the fiasco that was the war’s first big battle. President Lincoln had no fit commanders, so he promoted Ohio major Irvin McDowell three ranks to brigadier general (quite a jump!) and gave him around 30,000 inexperienced volunteers to make an army with. But McDowell noted that quickly forging an army from farmers, fisherman, and felons was impossible. Lincoln’s response? The Confederate forces were just as motley.

Inexperienced officers allowed McDowell to only deploy a little over half his army. Nevertheless, according to the American Battlefield Trust, McDowell’s forces drove back Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard’s men before Stonewall Jackson’s rally and Confederate reinforcements repelled them. The retreat was initially orderly. But the American political class, which had been observing the battle like a sporting event, blocked the main line of retreat with their carriages. Trapped between the spectators and pursuing Confederates, the men panicked and rushed back to D.C. in the “Great Skedaddle.”

While most of the spectators emerged unscathed, a few thrill-seekers were not so lucky. Governor William Sprague of Rhode Island was nearly killed after Confederate pursuers shot two of his horses. Judge Daniel McCook of Ohio was nearly shot, too. Most famous of all, Representative Alfred Ely of New York was captured and spent nearly half a year in a Confederate prison. Lincoln learned that he was going to need a real army to win — without interference from politicians.

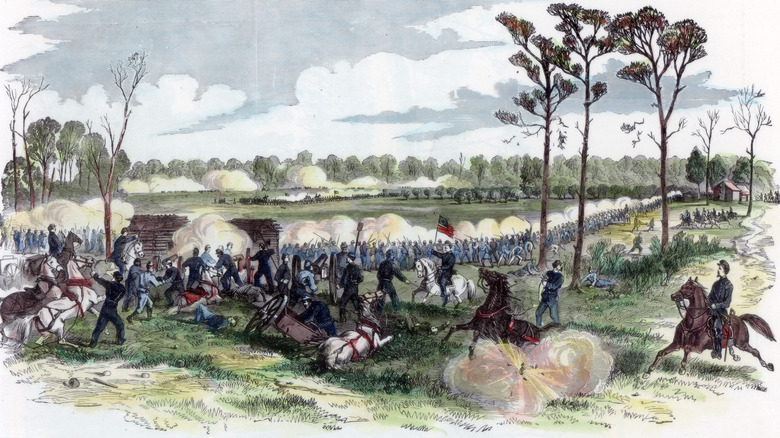

Antietam, 1862: Burnside Bridge

In 1862, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under General Robert E. Lee invaded Maryland, where they ran into General George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. At the ensuing Battle of Antietam, former Confederate Sec. of State Robert Toombs made his name for his heroic defense of the Lower Bridge.

According to the American Battlefield Trust, Ambrose Burnside, one of McClellan’s subordinates, was tasked with crossing Antietam Creek at the Lower Bridge. Due to a mix-up in orders, however, Burnside’s forces made three uncoordinated attacks across the bridge, which was defended by a mere 500 Confederates under Toombs. Toombs’ men held off Burnside’s numerically superior force for four hours, and were still standing by 1 p.m. that afternoon.

The tragedy of this situation is not only that Union forces achieved virtually nothing in their attacks, but that they could have achieved everything with more patience. Before attacking, the National Park Service notes that Burnside had sent Isaac Rodman to locate another crossing downstream. Eventually, he found one at Snavely Ford. Had Burnside waited, many Union lives might have been saved. What did his assaults achieve? Not much. Toombs simply withdrew his men to avoid being flanked, losing 120 men overall.

Burnside’s failure became immortalized in the name “Burnside Bridge.” Nevertheless, Lincoln later appointed him commander of the Army of the Potomac. He would lead it to the disaster at Fredericksburg in 1863. Despite his success, Toombs resigned his commission out of frustration with Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government. He would eventually flee to France to escape an indictment for treason after the war.

Ft. Donelson, 1862: Pillow breaks out and then entraps himself

According to the American Battlefield Trust, Brigadier General Gideon Pillow owed his position to his role as President James Polk’s legal partner. From a court-martial in Mexico to a failed political career in America, he was hardly someone to trust with an army. Despite his history of failure, Pillow was tasked with defending Fort Donelson, Tennessee, against Ulysses S. Grant’s advancing forces.

As it became clear that Donelson would fall, Pillow and his superior general John Floyd massed their forces for a breakout. Pillow’s men actually drove Union forces back, but according to American History Central, the general decided to withdraw to his men’s trenches to resupply instead of pushing their advantage, throwing away all their gains. A Union counterattack forced the Confederates back into the fort.

In a farcical series of events, Floyd transferred command to Pillow and fled across the Tennessee River. Pillow then transferred command to Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner and fled, too, deeming himself too important to be captured. Buckner surrendered the fort and was thus held responsible for the defeat, despite Pillow and Floyd’s cowardice.

Pillow’s actions led Grant to comment to Buckner that had he captured Pillow, he would have released him. He was too much of a liability to his own side to waste in captivity. Grant’s assessment was dead-on. At Stones River in 1862, Pillow was caught hiding behind a tree instead of leading his troops.

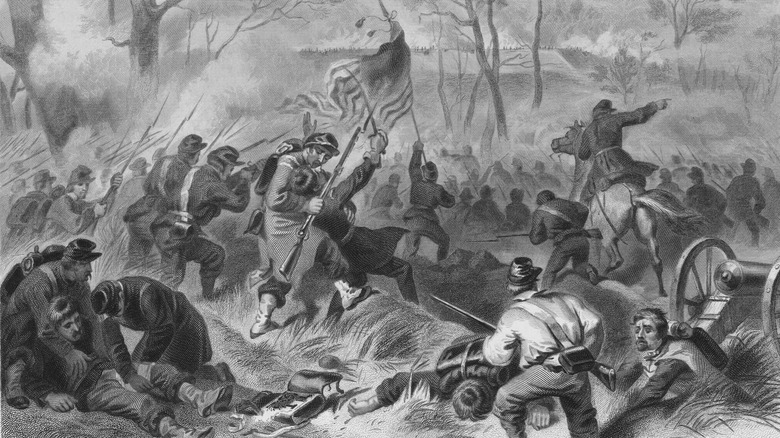

Shiloh, 1862: Don't celebrate too early

In 1862, the first major battle of the Western Front pitted Ulysses Grant against veteran Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnston. At Shiloh, a small Tennessee town, the Confederates looked to smash the Union advance into Mississippi, using speed and surprise to their advantage. Through a series of rapid and brilliant maneuvers, Johnston’s forces, per the American Battlefield Trust, outflanked Grant’s men, pushing the U.S. Army onto the banks of the Tennessee into an area called the “Hornet’s Nest.” Grant’s men hunkered down and held off repeated Confederate charges, even shooting and killing Johnston.

General P.G.T. Beauregard, transferred away from Virginia, took over after Johnston’s death. Although Union forces were stretched to their limit, his own army had suffered 10,000 casualties. Darkness and faulty intelligence convinced Beauregard to telegraph Richmond claiming victory and postpone the final attack to the next morning. Although historians disagree on the correctness of Beauregard’s actions, the battle was not over.

Unbeknownst to Beauregard, Gen. Don Carlos Buell arrived at 6 a.m. with nearly 20,000 reinforcements. The outnumbered Confederates now had no chance of winning and retreated to Corinth, Mississippi. The blow to the Confederacy was enormous: Grant now had a clear path into Mississippi, and the Confederacy had lost its best general.

Stones River, 1862/1863: Cheatham's drunk attack

New Year’s Eve is normally a time for new beginnings and celebration. But for the men of the Union Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of Tennessee, New Year’s Eve 1862 and New Year’s Day 1863 were spent fighting each other in the cold Appalachian winter. At the Battle of Stones River, the Confederate defeat was worsened when General Benjamin Franklin Cheatham celebrated New Year’s instead of doing his job.

During Stones River, the Confederacy’s Braxton Bragg and the Union’s William Rosecrans planned to break each other’s right flanks. Bragg seized the initiative and attacked first, forcing Rosecrans into defensive posture. The Confederate left, under Irish-born general Patrick Cleburne, spearheaded the attack but soon found its flank unprotected. Cleburne’s colleague, Major General Benjamin Cheatham, had not committed his forces in full support of Cleburne as Bragg had planned.

Cheatham was supposed to strike his opposite, Philip Sheridan, with the full force of his division. Instead, according to the National Park Service, Cheatham sent individual brigades to attack piecemeal. Thus, Sheridan had time to repel his opponents, reorganize, and repel the next wave. Cheatham’s men were slaughtered.

Why was the general so incompetent that day? According to Cheatham’s critics, he and many of his men, for some reason or other, were drunk on good Tennessee whiskey. Their movements were uncoordinated, they struggled to advance against the enemy lines, and Cheatham appears to have had no idea what was going on. His failure to break Sheridan allowed Rosecrans to win the day, forcing Bragg to retreat into Eastern Tennessee.

Chickamauga, 1863: The gap that wasn't

In 1862-1863, the Confederacy managed to put together a new army, the Army of Tennessee under General Braxton Bragg. Bragg led his army to a series of tactical victories in Tennessee, but since he did not follow up on them, Union general William Rosecrans marched on the railroad hub of Chattanooga on the Georgia-Tennessee state line. Bragg decided to encircle his enemy, but friction with his subordinates, who hated him (and vice versa), doomed the plan. Yet Bragg did not simply retreat deep into Georgia as Rosecrans expected. Instead, he concentrated his forces along Chickamauga Creek near the state line and made a stand, forcing the federal army into a fight it did not expect.

At Chickamauga, the two sides battered away at each other in a horrendous battle that saw a lot of close combat with bayonets. Despite bloody assault after bloody assault, Rosecrans’ lines held. Then inexplicably, the normally competent Union general made a colossal error that cost him the battle and nearly destroyed his army. The American Battlefield Trust notes that as the engagement progressed, Rosecrans believed that a gap had developed in his line. He pulled back a division to plug it. The only problem? The gap had never existed. In pulling back men to plug this nonexistent gap, he had opened up a real one. Confederate forces, incredulous at their luck, charged through and broke Rosecrans’ army, which retreated to Chattanooga. Fortunately, Bragg did not pursue him, allowing his forces to rally the next chapter of the action two months later.

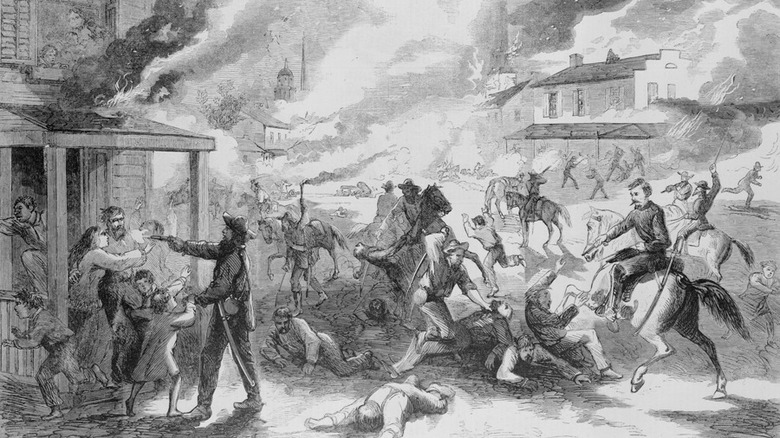

Centralia, 1864: Bloody Bill lives up to his name

Missouri was one of the four slave-holding border states that opted to remain part of the United States in 1861, but it hosted a significant population of Confederate sympathizers, which rose up against Union forces there. According to the American Battlefield Trust, the war in Missouri, unlike the main theaters, was a no-holds-barred guerrilla conflict that saw horrific massacres. Among the most notorious was the 1864 Centralia Massacre, when untrained, unarmed Missouri farm boys were sent to fight veteran Confederate guerrillas and lost.

According to American Experience, “Bloody Bill” Anderson lived up to his name. His pro-Confederate raiders terrorized towns, robbed civilians, and raped and killed slaves. After his men massacred a train of unarmed Union recruits at Centralia, local Union commanders sent the 39th Missouri Mounted Infantry to stop the veteran guerrilla force. But in their haste, the commanders had not even bothered to properly equip the men, let alone train them. Anderson’s men left Centralia and hid behind a hill outside town. The unsuspecting men advanced, followed, and were promptly massacred.

Centralia was no ordinary massacre. While commanders often respected dead soldiers’ bodies, Confederate guerrillas observed no such niceties. Anderson, who had earned his stripes fighting Native Americans on the frontier, had also picked up their practice of scalping dead opponents. He now meted out this treatment to his opponents, writing his place in Civil War history as the most brutal commander. Among his subordinates who first made his name was a young man who would later become America’s most famous outlaw, Jesse James.

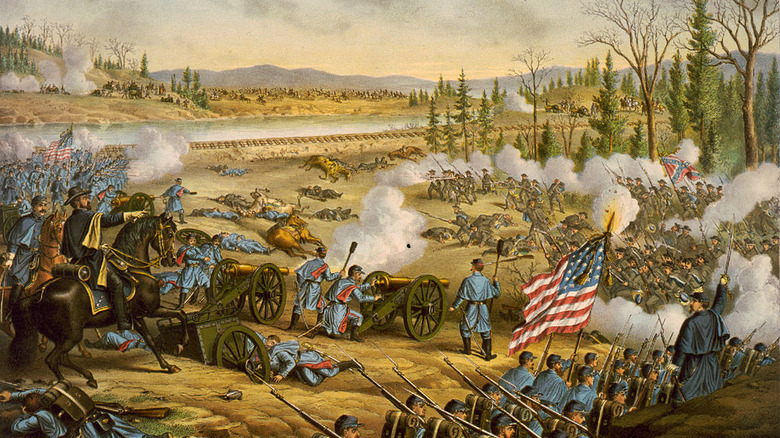

Battle of Franklin, 1864: Hood's suicidal assault

In 1864, the Confederate Army of Tennessee abandoned Atlanta and the Confederate war industries to General Sherman’s army and retreated into Tennessee. According to the Tennessee Encyclopedia, double amputee general John Bell Hood’s depleted army now attempted to trap Union forces near Nashville in a bid to raise the flagging Confederate morale. After a failed encirclement of said Union forces, an embarrassed Hood’s desire for revenge resulted in the war’s worst blunder bar none, one which permanently broke the Army of Tennessee.

Confederate soldier Sam Watkins described the horror of the battle, which he called the “grand coronation of death.” Hood threw 23,000 men against Union hilltop positions near Franklin, Tennessee. Confederate forces, without artillery support and armed with single-shot muskets and rifles, stood no chance against the U.S. forces on the high ground, who were armed with 16-shot repeating rifles. Hood’s men would pay for their commander’s rash decision with their lives.

Unsurprisingly, the battle was a horrific massacre, one that Watkins likened to a harvest by the Angel of Death. Hood’s outgunned and outnumbered soldiers suffered over 6,000 casualties (20% of his army), including seven generals (six killed, one captured) and an astounding 63 dead regimental commanders. Even by Civil War standards, this was catastrophic. Lower-ranking officers were forced to take charge of larger divisions due to a lack of commanders. At Nashville, the Army of Tennessee was routed and reduced to a mob of 20,000 men, a sad end for an army that had fought so hard and so well despite its commanders.

Generals drink, men die

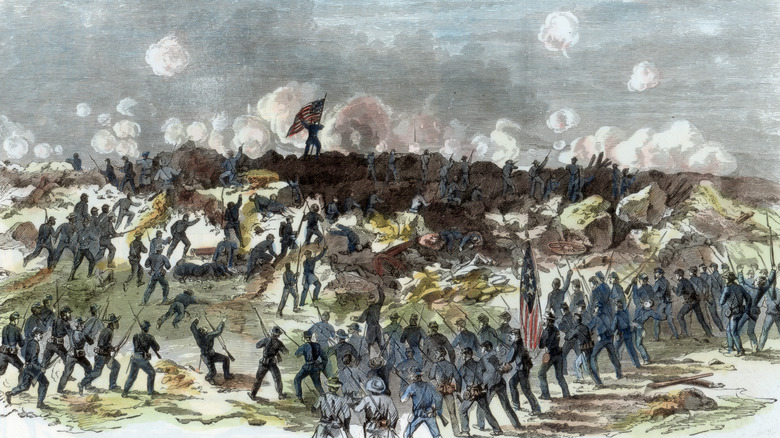

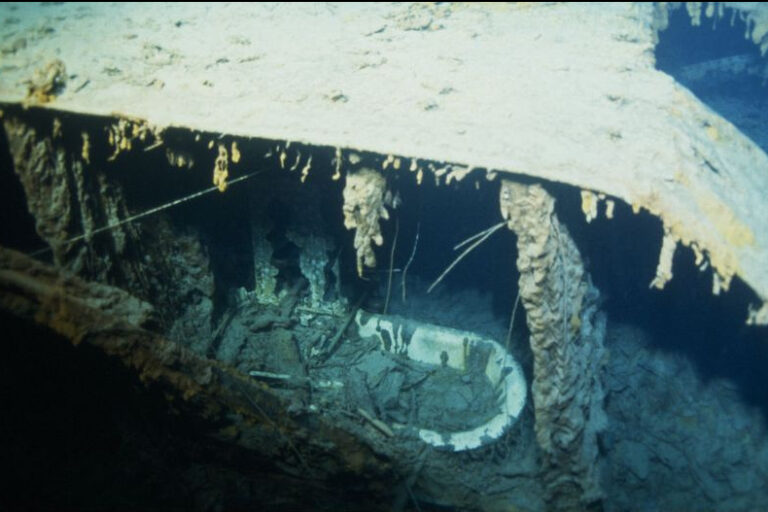

In 1864, General Grant’s army marched on Richmond looking to end the war. General Beauregard (again!) barred the road at Petersburg. According to Penn Live, a unit of Pennsylvania coal miners blew up the Confederate fortifications by digging under them and planting explosives, leaving behind a massive breach that Union forces could rush. The chance to win the war was at hand. However, lackadaisical generals and unclear orders doomed the attack and sent 6,000 mainly Black soldiers to their graves.

According to the American Battlefield Trust, General Ambrose Burnside had originally planned to send Black regiments under General Edward Ferrero into the breach. Their superior, General Meade, however, nixed the plan. The white troops had more battlefield experience, so Burnside’s men drew lots to decide who would get the unenviable job of leading the attack. Brigadier General James Ledlie drew the short straw.

According to Historic Petersburg, Ledlie’s forces entered the crater and milled about at the bottom awaiting orders. A Confederate counterattack slaughtered the Union soldiers like sitting ducks. Inexplicably, Burnside sent Ferrero’s Black regiments into the crater. As historian Elizabeth Varon notes, the Black troops received no quarter from their Confederate opposites. So bloody was the massacre that even some Confederate commanders questioned the necessity of the brutality meted out to the Black regiments.

To add insult to injury, Varon notes that neither Ledlie nor Ferrero actually led their units. Both generals stayed behind the lines in a bunker drinking rum while more than 6,000 of their men were slaughtered in vain. Grant was forced into a nine-month siege of Petersburg that would drag the war into 1865.

Here's How Early Humans Lived Through The Ice Age

Japanese Weapons That Could Have Completely Changed World War II

How A Computer Virus Might Have Saved The World From Nuclear Attack

Why The Oldest Person To Ever Live Might Have Been A Fraud

What Is The Significance Of Baptism In The Bible?

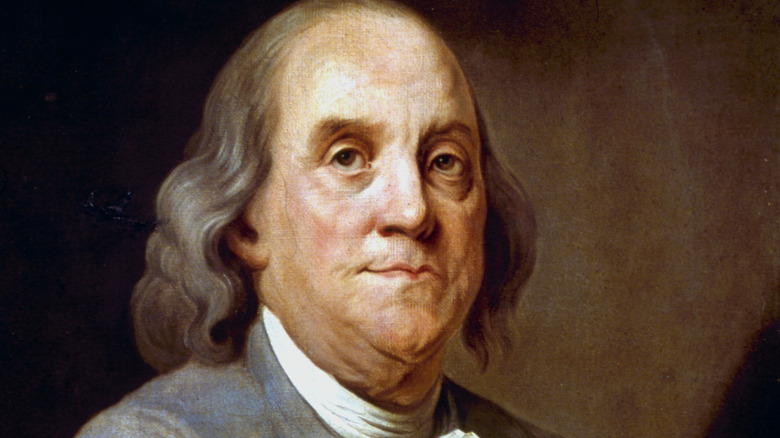

The Truth About Benjamin Franklin's Relationship With His Wife

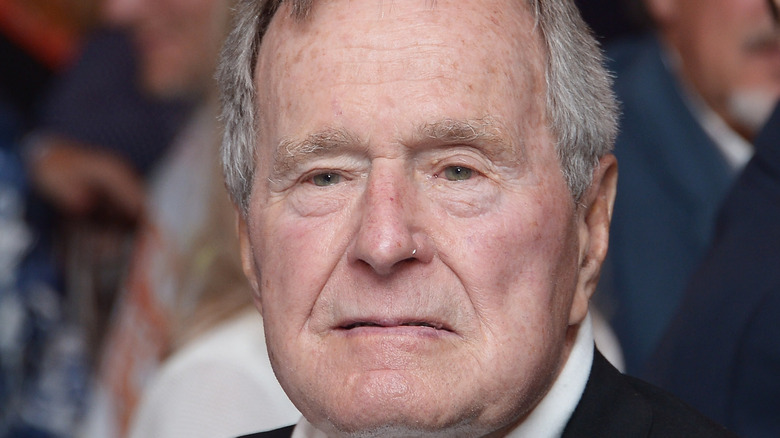

How George H.W. Bush Once Evaded Being Eaten By Cannibals

Why We Don't Know Much About George Washington's Religious Beliefs

How Many Victims Did 'Gorilla Man' Earle Nelson Have?

The Untold Truth Of The Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section