The Fascinating History Of The Didgeridoo

In case you’re wondering: no, a “didgeridoo” isn’t a wondrous, magical kids’ toy of imagination brandished by Mary Poppins, nor is it a rare Dungeons and Dragons trinket dug up from the bottommost recesses of a wizard’s ancient trunk of treasures. It is, though, onomatopoeic. Western settlers who came across Aboriginal peoples in Australia found them playing the distinctive, drone-like, warbling bass tones of these long wooden instruments, as Wakademy describes. Someone said, perhaps while bobbing their head, “What are those?” Someone else raised a hand and said, “Listen to that bass! It goes di-ge-ri-doo!”

In case you’ve never heard a didgeridoo (officially Australian governmental spelling: didjeridu), give a listen to player Lewis Burns on YouTube, possibly around the 45-second mark. While it’s tempting to make comments like, “oh my gosh, it’s neolithic dubstep!” instead listen to Burns’ breathing. Try to identify when he takes a sharp inhalation, and then recognize that his lips never leave the instrument’s aperture. He never stops exhaling, for minutes on end, and the tone coming from the instrument never pauses; it just changes tempo and rhythm. Longer tones and fewer rhythmic changes: fewer breaths. Shorter tones and more frequent rhythmic changes: more breaths. The same type of technical training, called “circular breathing,” is necessary to play one of Earth’s other most difficult instruments, the Scottish bagpipes, and others like the Armenian duduk.

So where did this didgeridoo come from, exactly? How does it work, exactly? Time to take a didgeridive.

A variety of instruments across various aboriginal tribes in Australia's Northern Territory

Before continuing further, as Wakademy explains, it’s important to note that the word “didgeridoo” refers to an array of related instruments, such as the mago in the west of Arnhem Land, the northeast part of Australia’s Northern Territory. It’s shorter (1-1.4 meters), rounder, and tends to produce more harmonics (overlapping, resonant frequencies that you can hear in guitars, human voices, and so on). The yidaki, by contrast, which comes from the northeastern tip of Arnhem Land, is longer (~1.6 meters), and tends to produce a thinner, bristling tone similar to a trumpet.

Of course, not all indigenous peoples in Australia crafted digeridoos in the millennia they’ve occupied the Australian continent. There are over 500 distinct aboriginal cultures, languages, and lands, after all, per Survival International. Digeridoos are native to the Northern Territory, as ABC News tells us, and have become modernly adopted across a wider set of regions. Depictions of digeridoos adorn Northern Territory rock art that belongs to an era of time dating from about 0-500 CE, although, as Spirit Gallery says, these paintings still await carbon dating. In Kakadu National Park, specifically, there’s evidence of 11 distinct styles of digeridoos in art spanning across various environmental epochs.

Digeridoos have also come to be connected to Aboriginal “Dreamtime” myths, or “Tjukurpa,” which themselves relate to beliefs of the original humans on the Australian continent some 50,000 years ago, as dated by the University of New South Wales.

Deep drones, high harmonics, and lots of rhythm

Digeridoos are distinctive for their deep drones and high-pitched overlapping harmonics, kind of like an instrumental version of Mongolian throat singing (a whole other journey you can start on YouTube if you’d like). Much like other “fixed pitch” instruments, each digeridoo is tuned, essentially, to a single tone: A#, C, Eb, and so on. A longer instrument will be deeper in tone, and a shorter one, higher.

This doesn’t mean that digeridoos just play one, sustained note without variation. Puffing one’s cheeks, moving around your tongue, tightening the lips (as with a trumpet) changes the sounds. There are barks, yelps, whistles, growls, grunts — basically, anything you can do with your throat. And this is a key difference between the digeridoo and, say, a flute, as Spirit Gallery explains. A flautist doesn’t use her vocal chords; she purses her lips and expels air, only. A digeridoo, however, generates its sound from the human throat; it requires exhalations plus vocalizations. It’s a magnifier, more or less, for whatever vibrations a player makes in the throat. This allows for an impressive level of variation and creativity while playing.

Circular breathing is the key to unbroken digeridoo tones. Trained vocalists know that sustaining long notes depends on breath conservation — expelling minimal air in a controlled fashion. Circular breathing, as Healthline describes, involves similarly precise control over breath, such as exhaling into the cheeks at the same time as inhaling through the nose.

Hand-hewn from trees and carried to performances worldwide

Traditionally, making a digeridoo starts with finding a suitable tree: not too thick, not too crooked, and not too long. Digeridoo ambassador and world-renowned player Djalu Gurruwiwi crafted his own digeridoo — a yirdaki, specifically — on camera back in 2004 (video on YouTube). The inside of the tree has to be bored out, its edges sawed, its surface hewn and smoothed, and finally, taken to a body of water to clean before allowing to dry.

Gurruwiwi, and others like him, have helped not only to legitimize the digeridoo as a complex musical instrument worthy of attention (feel free to listen to William Barton play with an orchestra, also on YouTube), but to the status of indigenous peoples across Australia. Gurruwiwi, for instance, hails from Birritjimi land, which got caught in a sadly typical colonial land grab and now suffers from horrific poverty, as ABC News reports.

This is especially shameful because digeridoos have become part and parcel of the heritage of regional Aboriginal peoples, and emblematic of what’s known as “Dreamtime” myths, which, as Aboriginal Art Australia explains, describe how the world and its people were created. There’s a great emphasis on the balance of nature, animism, and natural laws related to human conduct, including rituals connected to marriage, death, and prominent cultural narratives. Nothing could be more perfect for such tales than the resonant, reverent, “Om”-like tones of the digeridoo.

The Real Reason Why Clouds Move

Things Fans Might Not Know About The Addams Family

The Truth Behind Chicken Pox Parties

The Bizarre True Story Of The Flatwoods Monster

This Gross Ingredient Was Once Used As A Popular Teeth Whitener

Here's How Many People Have Died At Disneyland

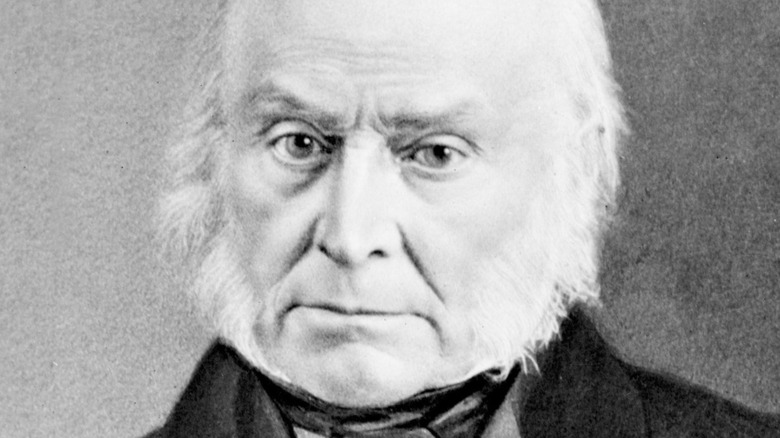

Stories From History That Sound Fake But Are Completely Real

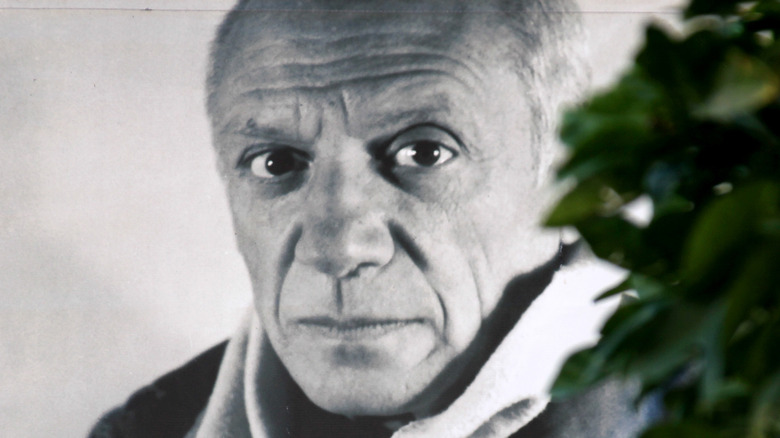

What You Didn't Know About Pablo Picasso's Blue Period

Here's How John DeLorean Was Acquitted Of All His Charges

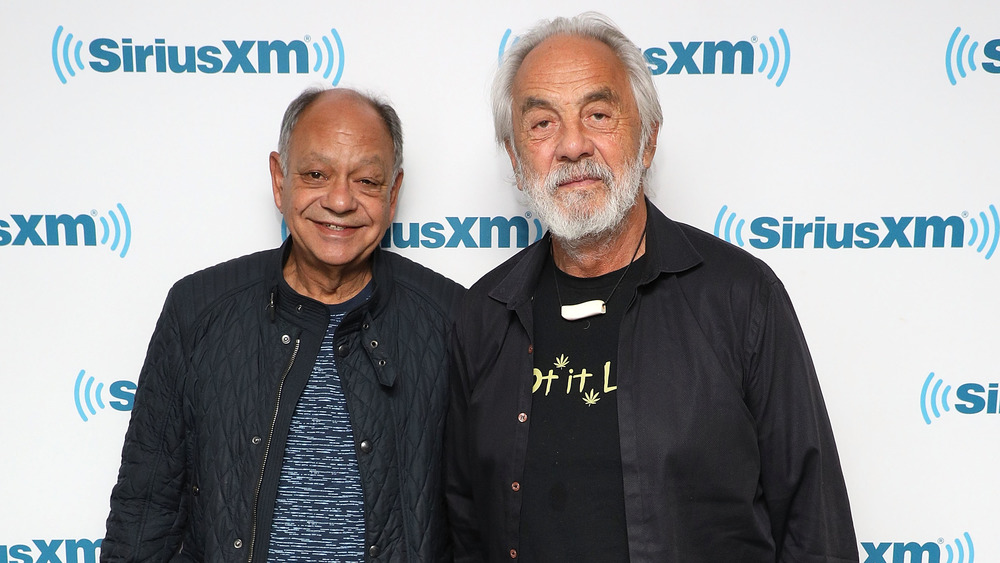

Cheech And Chong's Net Worth Is Higher Than You Might Think