The Legend Of Fairies Explained

“Have you a little ‘Fairy’ in your home?” So asks an 1800s British manufacturer of “Fairy Soap.” Yes, little tiny beings have been flying around the universe forever, it seems, mostly as whimsical fodder of fairy tales which have been told for centuries. One of the most recent studies of this magical brand of folklore, reports Science, found that many stories about fairies may be so old that they began as “oral stories that left no written versions.” One tale, “The Smith and the Devil” (in which a blacksmith sells his soul and uses trickery to get it back), is European and can be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European people. That means that some fairy tales, and the creatures who star in them, could date as far back as 6,000 years ago. How cool is that?

Throughout the entire world, fairies (otherwise known as bodies, brownies, elves, enchanters, fay, genies, gnomes, goblins, gremlins, hobs, imps, leprechauns, mermaids, nymphs, pixies, pucks, sirens, spirits, sprites, sylphs, and nisses, according to your local thesaurus), can take all shapes and forms. According to Ancient Origins, fairies live a metaphysical existence but are able to cross into our physical world. And true to their history, we have brownies representing girl scouts, garden gnomes and fairy gardens in our yards, bands like the Pixies, and all manner of other references to our fair, mostly fun little friends. Here’s a brief rundown on fairies and how they have shaped history.

Fairies and Greek mythology

Most scholars regard fairies as a type of ancient mythology, although others refute that they originated in Greece. Rather, according to Realm of History, the early tales of 60 centuries ago helped shape the mythological gods and their counterparts in Greek and Roman history. Most of the central mythological figures resemble humans in shape and size. Apollo, Poseidon, Zeus, Aphrodite, Athena, Hestia, Hephaestus, Ares, Artemis, Demeter, Hera, and Hermes — all are the life-size, legendary Twelve Olympians, and in history, they frequently interacted with nymphs, satyrs, sirens, and more. Timeless Myths explains that nymphs in general are considered fairies, and they were around when the Greek poet Homer wrote the Iliad and the Odyssey in the eighth century BC.

Although the Twelve Olympians were gods and goddesses, nymphs were not, but they still had important roles, according to Theoi Greek Mythology. Many of them were female and were charged with caring for the Earth. From water to flowers to trees to even cooling breezes, nymphs protected the forests and the animals within them. Satyrs could range from “demi-gods” like Leneus, who oversaw wine-making, to Kerkopes, a pair of tiny troublemaking bandits (Zeus turned them into monkeys). Then there were sirens, which Greek Mythology describes as “half-birds, half beautiful maidens” whose singing attracted sailors to their doom. They “were fated to die” if any sailors survived, and when Odysseus got by the maidens without harm, the sirens took to the sea in a fit and subsequently drowned.

The fairies of Great Britain

Historic UK claims England’s fairies date back to the 13th century, when historian Gervase of Tilbury described them. At the time, belief in fairies was so prevalent that most people declined to mention them by name. Instead, they were referred to as “Little People” or “Hidden People.” In England, the variety of fairies is a pleasant bouquet of those with or without wings, the tall and the small, either beautiful or hideous. Some can even render themselves invisible. In religious circles, fairies were believed to have been fallen angels, “neither bad enough for Hell nor good enough for Heaven.” British Fairies attributes this to the gates to both places closing after Lucifer reared his ugly head.

Another theory submits that Jesus turned some children into fairies after their mother, who had 20 kids in all, hid some of them because she was ashamed of the number. They flew away and were never seen again. Even the Christian church supported the existence of fairies — a Montgomeryshire minister once theorized that “God allowed them to appear in times of great ignorance to convince people of the existence of an invisible world.” According to Between Worlds, fairies aren’t just for those of faith or the superstitious. One educated physician of Galloway said he encountered an entire group on a road late at night, which parted and bowed to him as he passed. A man from Yorkshire even claimed he caught one, but it escaped from his pocket.

The Cottingley Fairies were England's most famous fairies

In 1917, cousins Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright were scolded for “returning home wet and untidy” after playing in the water at Cottingley Beck in West Yorkshire. The girls said they had gone there “to see the fairies,” according to Historic UK. When they were laughed at, Elsie borrowed her father’s camera, and the girls went back to the little brook to photograph their proof. Arthur Wright developed film himself in his own darkroom. Amazingly, the image depicted Frances lying on the grass and complacently gazing at the camera while four tiny, winged, beautiful fairies played instruments and danced in front of her. Wright, a professional photographer, was sure the image was fake. Elsie’s mother Polly, however, believed the image was real.

Next, Elsie and Frances produced another photograph, showing Elsie with a gnome. In 1919, according to Quartz, Polly Wright was able to get both images to the Theosophical Society, which investigated “unexplained phenomena.” They were a hit. Even author and physician Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was impressed and talked the girls into producing more photos as evidence in 1920. Skeptics came out of the woodwork, and in 1978, according to the Museum of Hoaxes, James Randi found images of the same exact fairies in Princess Mary’s Gift Book, which was published in 1915. In 1981, Elsie Wright admitted the photos were fake, although Frances did not. Both ladies, however, maintained that they really did see fairies at Cottingley Beck.

The fairies of Ireland

Fairy folklore in Ireland, according to Celtic Wedding Rings, comes from Celtic, Greco-Roman, and German beliefs. Their legends began with pagan storytellers and later combined with Celt and Christian folklore to evolve into modern-day stories. Naturally, the leprechaun is the best-known of Irish fairies, a tiny mischief-maker wearing a green outfit. If you’re lucky enough to catch one, he is bound to grant you three wishes. Alternatively, reports U.S. Money Reserve, one Irish farm couple who caught a leprechaun was granted only one wish. But their list of wants was so long that the little guy finally advised looking for a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow. A legend was born.

Mark Doherty at Vagabond Tours of Ireland claims that today, “most Irish have no beliefs in the fairy folk,” though they do retain respect for the beliefs of their forebears. All the same, Doherty says, “Asking an average Irish person, ‘Do you believe in the fairies?’ will get a response similar to asking an average Irish person, ‘Are you stupid?’ ” Yet, acknowledgment of Irish fairies is still firmly entrenched in the culture, and talk of fairies and pixies remains common — even certain websites, like Ireland Before You Die, give lists of where visitors are most likely to find them.

Feminist fairy tales of France

Wonders and Marvels confirms that the earliest written fairy tales were done by Countess Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy (pictured) in 1697. That same year, Charles Perrault wrote Tales of Mother Goose, which remains far more familiar to today’s readers. But d’Aulnoy was more inspired than Perrault. According to The Local, she was only 15 years old when she was kidnapped, possibly with the aid of her father, and forced to marry a wealthy baron who was 30 years older than she. When d’Aulnoy and her sympathetic mother were suspected of trying to have the baron executed, the girl fled across Europe. She eventually returned to Paris, where she set up one of the first literary clubs for women. The ladies found solace in writing fairy tales, generating two thirds of France’s known stories between 1690 and 1715.

It was not until 1860 that there were efforts to collect and record such folktales, according to French Fairy Tales and Legends. Between 1871 and 1914, hundreds of folklore books about fairy tales, legends, and songs were published. They shared a common bond: Most centered around put-upon young girls who find freedom through interacting with fairies. Reading about them remained a highly popular pastime until World War I but resumed after World War II. Some Cajun fairy tales, such as those about the Grunch, the wolf-headed Rougarou, and Le Feu Follet, even managed to migrate over to Louisiana around the time of the Louisiana Purchase.

The American fairy

When settlers migrated to America, fairies apparently hitched a ride with them, resulting in some amazing folklore that is still talked of today. One journal from 1894 spoke of the good fairies and the bad pixies of Massachusetts, according to The Agora, which explained simply that “where people from a culture go, their spirits also go.” American history is rife with mostly Irish but also other geographically tagged fairy lore. American house fairies like Scottish brownies and Finnish tomtras are believed to still live in older homes and serve as protectors of the house — although tomtras tend to be somewhat mischievous. As late as the 2000s, A Letter from Hardscrabble Creek recounts a firefighter in Alaska who was chopping down a tree when it “shrunk down and a not-so-handsome little man about a foot tall with a beard and many wrinkles on his face stared up at me and screamed ‘Noooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo.’ “

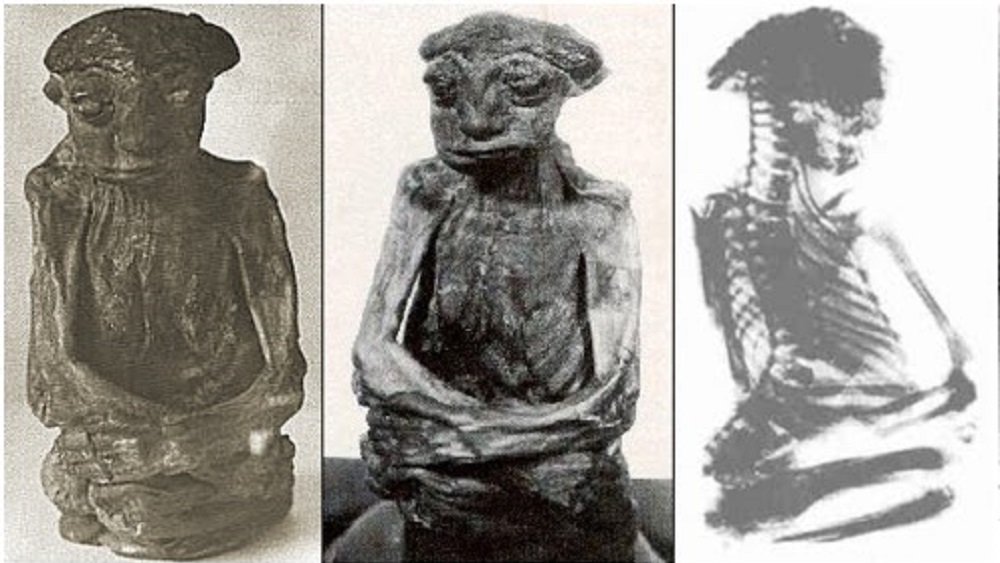

What most pilgrims didn’t realize until later is that indigenous Americans had their own kinds of fairies, known as “little people,” according to Other Worldly Oracle. These tiny beings helped children but also taught shamans their healing powers. The Shoshone call them Nimerigar. Cherokee lore has three different types of fairies: Dogwoods are good-hearted, laurels are mischievous, and rocks are aggressive. The list goes on and on, including “proof” in the 1930s, when a tiny mummy (pictured) was discovered in Wyoming, complete with an adult set of teeth.

There are good fairies

Around the world, fairies come in literally hundreds of forms and temperaments, and many of them are friendly and helpful. Brownies, for instance, are social little guardians who help do housework and odd jobs, says Origins of Fairies. In Scottish lore, this can prove difficult, since they have “no separate toes or fingers.” Some of the most alluring fairies are “merfolk,” which Real Fairies explains are mermaids and mermen who live in the sea, hunting for food and watching over their young ones. Gnomes are shy little people wearing red caps who mostly eat fauna. Due to their short stature — around nine inches — they try to remain unnoticed. Their most powerful ability is to heal sick and injured animals, making them a boon to the forest world.

Perhaps one of the best-known fairies, according to Writing in Margins, is the ever-endearing fairy godmother. Yep, the benevolent, magical, grandmotherly spirits of tales like Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella date back as far as 1621. Their job is to dispense wise advice, bestow gifts like beauty and a lovely singing voice, and act as a guardian over their young, usually female charges. Sometimes, they look after young men as well, such as with Tom Thumb’s “kind Midwife & good Godmother.” Fairy godmothers may preside over the birth of a new baby, as well as its christening, lest an evil fairy come along and steal the child. Notably, an angry fairy godmother is able to dispense a curse if needed.

There are bad fairies

Fairy godmothers aren’t the only ones to put a curse on those who displease them. Bad fairies can range from simple tricksters, like leprechauns, to those who kidnap children, like the “unseelie court,” says British Fairies, which also maintains that all fairies can go bad if they are rubbed the wrong way. The Origins of Fairies provides a list of fairies who are always bad no matter how they are rubbed. These include banshees, who appear to tell of an impending death, goblins and bug-a-boos, which are always up to no good, and Black Annis, the blue-faced hag who is responsible for the wicked storms in the Scottish lowlands. There and also in America, the Jack-o-Lantern haunts marshy areas and lures unsuspecting travelers to stinky bogs from which they never return.

Ancient Origins talks about fairy rings, which, while intriguing, are something to be avoided. They are geared toward unsuspecting men who, enchanted at the sight of beautiful little creatures dancing in a circle, are tempted to join the party. By doing so, they become trapped and doomed. Depending on which lore you believe, you might become invisible to humans as you remain trapped in the fairy world. Or you can lose an eye. Worse yet, you will be forced to dance around and around the ring until you “die of exhaustion or madness.” Some fairy rings are marked by a border of mushrooms. Just don’t step inside of one.

The legend of the Tooth Fairy

In America, the Tooth Fairy reigns as the best ethereal being by far. Although she takes a backseat to Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny, the Tooth Fairy brings one heck of a great gift: cold, hard cash, left under your pillow while you sleep. Per Salon, although the Tooth Fairy has been an oral tradition (pardon the pun) since about 1900, the first written documentation of her was in a 1927 play written by Esther Watkins Arnold. Other cultures dispose of their discarded baby teeth by throwing them to the sun, or into a fire, or some other method. But, this brings no reward. 123 Dentist found a survey stating that the average American kid gets $3.70 per tooth.

Although other countries also celebrate the coming of the Tooth Fairy, there are conditions. In Europe, only the sixth tooth coming out is deemed special enough for a gift. In France, the Tooth Fairy is a mouse or a rabbit. In Spain, Ratoncito Perez is a little rodent who leaves gifts in exchange for teeth, according to Pets Lady. But it is France’s tradition, according to Kids Healthy Teeth, that America follows most closely. French children leave their tooth in a shoe and receive a coin in the morning. Nobody seems sure why American children leave it under their pillow — and it’s notable that the Tooth Fairy often resembles Mom or Dad, who exchanges the tooth for a few bucks.

How to spot a fairy

So, with all of this information in mind, just how does one go about finding a fairy? As Fabulous Fairy Tales notes, fairies flourish anywhere from houses to gardens to forests. They can live in flower pots, trees, water, or even their own tiny kingdoms underground. But what do fairies look like, and what do they wear? It’s hard to say. Some are tiny, or even invisible. If they wear clothing at all, they seem to like solid colors, from their red hats to green outfits to blue dresses. They can be miniature, beautiful maidens, nasty-looking old hags, wrinkled little men, or sometimes animals. Some of them can change their appearance at any time.

Catching a fairy is not easy. For ideas, the Vermont Institute of Natural Science recommends visiting their Fairy Town for ideas to build houses to attract fairies and to see where they live. There is even a fairy godmother on hand to dispense further advice, and yes, wearing your own fairy wings is encouraged. Alternatively, you can buy a fairy-catching kit or, better yet, make one of your own. Instructables recommends using a small net, picnicking inside a circle made with shiny objects and sweet treats, and wearing fairy wings as a disguise. Oh yeah, and you need a jar to observe the little creatures after you catch them. Just be sure to let them go afterward or turn them loose in your fairy garden.

Fairies remain among us today

As ol’ Raymond “Ray” Reddington says on The Blacklist, “I can only lead you to the truth. I can’t make you believe it.” Even those who don’t believe in fairies, however, may not realize how highly influential the wee ones and their stories have been on modern-day culture. Games Radar lists 50 movies that are based on fairy tales, including Disney classics like Cinderella, Peter Pan, Pinocchio, Sleeping Beauty, and Snow White. Even more recent films — notably Shrek, Splash, Labyrinth, and The Matrix are based, at least in part, on fairy tales. Then there’s The Brothers Grimm, a fictionalized version of what happens when the fairy tale authors encounter an actual fairy curse.

Granted, movies like Brothers Grimm and many others take much in the way of poetic license, acknowledges NPR. To make some of the more gruesome stories more palatable, modern adaptations have been applied. Take Snow White, for instance, who originally was only seven years old and whose own mother plotted to kill her. Then there’s the first version of Cinderella, in which Horror Fuel reveals that one evil stepsister slices off her toes and the other cuts off her heel in order for her foot to fit into the magic slipper. And at the end, a sweet little bird pecks their eyes out as Cinderella marries her Prince Charming. Who wants to see that?

Here's How Many Dead Bodies Have Been Found In The Hudson

Guinness World Records That Are No Longer Accepted

This Is The World's Oldest Bottle Of Wine

Weird Things You Didn't Know About The Smurfs

The 1922 Riots That Were Started Because Of A Clothing Item

Coronavirus Myths You Need To Stop Believing

Doctors Report First Known Case Of Person Who Urinates Alcohol

Baboon Recreates Iconic Lion King Scene

Who Will Be The World's First Trillionaire?

Strange Things That Happened On The Set Of Serial Killer Movies