The Legend Of The Sphinx Explained

The sphinx never really existed, but it’s probably one of the most mystifying creatures ever imagined. To some cultures it was a terrible monster, for others it was more like a guardian spirit, but for everyone, the sphinx was always a frightful and legendary creature.

Most people have probably heard of the Great Sphinx of Giza, the famous statue that sits not far from the Pyramids, but that is just one of many depictions. The ambiguous history of the symbol reflects the ambiguous nature of the sphinx itself. Sphinxes play with lines and boundaries like giant cats and a piece of string. They don’t care about sharp distinctions; they love transgressions and passageways. Whether benevolent or malevolent, a sphinx always keeps you on your toes. In most cultures, the sphinx is associated with knowledge and specifically with riddles. Be careful when answering, though — even the right answer can be treacherous. This is the legend of the sphinx explained.

The sphinx originated in antiquity

A fantastical creature that defies logic and comprehension, the sphinx appears in legends from all over the world. The sphinx may well be one of the most well-known figures in mythology. Emblematic of ambiguity itself, it is a beast whose infinite knowledge is coupled with infinite secrecy. According to the Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, the sphinx first appeared in Egypt, often depicted with the head of a man and a body of a lion, although variations incorporated terrifying combinations of ram and hawk heads as well. The sphinx can be seen on relics from the ancient Nubian and Minoan civilizations, though archaeologists like Nota Kourou aren’t sure if these sphinxes meant exactly the same thing as they did in Egypt.

As the sphinx traveled the world, it was modified to suit people’s needs while never losing its chimeral nature as a monstrous fusion that defies the laws of nature. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the sphinx got its wings in Asia. This alteration reappeared in later in Greece in the eighth century B.C. But no matter where it arrived, the sphinx was both revered and feared.

How the sphinx sprang forth in the Egyptian Delta

In Ancient Egypt, sphinxes were considered spiritual guardians, protector of passageways. They had a threatening majesty and were thus often placed at the entrances of tombs and temples. After all, who would dare try to sneak past such a terrifying beast? The Egyptian sphinx often wore the pharaonic headdress, the nemes, leaving no doubt as to its godly associations since the pharaohs were the closest link between man and the gods.

According to the Ancient Egypt Research Associates, the term for “sphinx” in Ancient Egyptian was “shesep ankh Antum,” which translates to “living image of Atum.” Atum was the original creator god in Egyptian mythology during the Old Kingdom, who created himself out of chaos and was incarnated every day as the setting sun. Just like the sphinx, Atum transgressed boundaries between being and nothingness, so it’s no surprise that the Egyptians associated such a mighty beast with their most formidable deity.

What is a sphinx if not two things at once? Just as the sphinx has two forms in its physical body, it was associated with both the creator god and the underworld. Aker (also known as Ruti), the deity who guards the gates of dawn and life after death, was also represented as a two-headed conjoined sphinx, taking the duality of a sphinx to another level. No matter where the sphinx was guiding you, it was considered a benevolent force, despite its awe-inspiring might.

A masterpiece that stands to this day

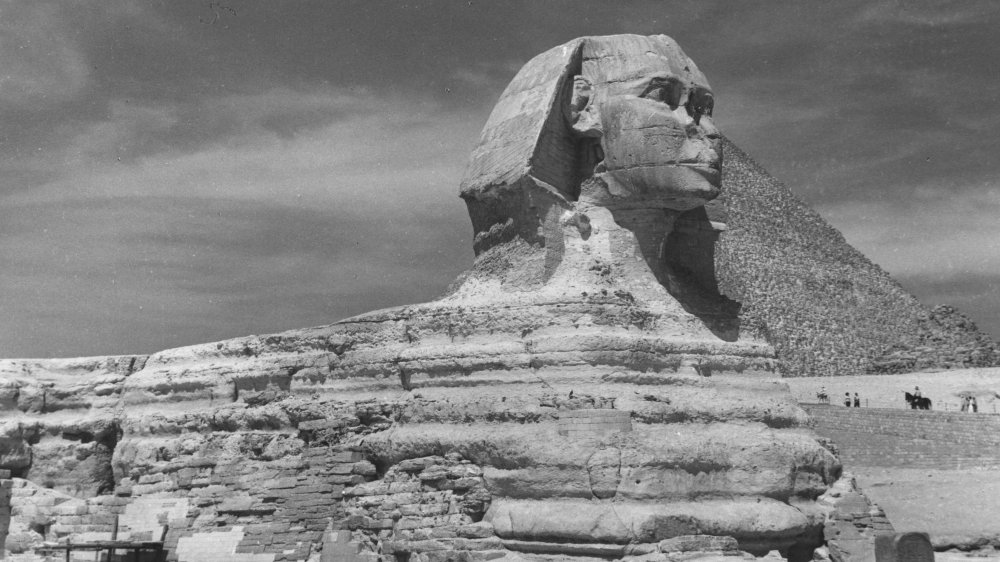

The most famous of the sphinxes is the one still majestically lying at Giza. Repeatedly unearthed and reburied by the sand through the centuries, the Great Sphinx of Giza is probably the most recognizable sphinx in history, its profile emblazoned on anything from cigarettes to typewriter paper. According to National Geographic, it’s unclear who exactly built the Great Sphinx, although estimates put its construction during the Old Kingdom, more specifically somewhere around 2558 and 2532 B.C.

The Great Sphinx has been called by many names: Horemakhet (Sun on the Horizon), Harmarkhis (Son of the Sun), and Abu-al-Hol (Father of Terror). It seems appropriate that a multifaceted creature should have so many titles. Though it bears a striking resemblance to the pharaoh Khafra, who reigned in the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (around 2570 B.C.), considering the date of his rule it’s likely that in his vanity he redid the face of the preexisting Sphinx to look like him.

All this does little to shed light on the meaning of the Sphinx, but that doesn’t stop archaeologists from guessing. According to Smithsonian Magazine, archaeologist Mark Lehner noticed that at the time of the summer solstice, when standing at the Great Sphinx, the sun sets halfway between the Khafre and Kufu pyramids: the formation looks just like the Egyptian hieroglyph akhet. Not only does this hieroglyph translate to “horizon,” but it was considered symbolic for life, death and rebirth.

The Great Sphinx's mysterious nose

The mystery of the Great Sphinx’s missing nose is one of its most enigmatic qualities, continuing to perplex archaeologists to this day. While the entirety of its massive body has suffered wear and tear over the years, from natural elements or touristic frenzy, its missing nose has been a constant, inspiring a variety of tales as to how this great beast came to lose what must once have been its most prominent feature.

Some claim that the nose was broken during Napoleon’s invasion from 1798-1801, blaming Napoleon’s soldiers and Mamluks for firing a cannonball into the face of the Great Sphinx. But according to Smithsonian Journeys, the Danish explorer Frederic Louis Norden had made sketches of the Sphinx in 1737, before Napoleon’s reign, and the Sphinx’s nose was already missing. The plot thickens.

Another theory comes from al-Maqrizi, an Egyptian historian who wrote in the 15th century that the nose was vandalized by a Sufi Muslim protesting the devotion shown to the statue. Mohammed Sa’im al-Dahr was said to have attacked the Sphinx in 1378, enraged at local peasants for praying to the Sphinx in the hopes that their crops would improve.

Regardless of how the Great Sphinx’s nose was broken, its scarred face is now one of its essential qualities, a testament to its fragmented nature.

How the sphinx journeyed across the Mediterranean

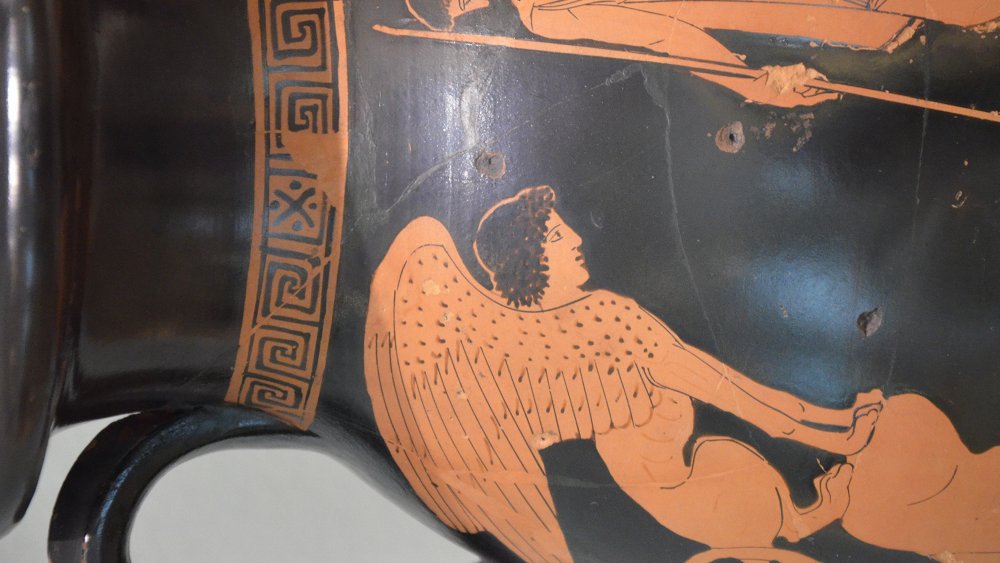

When the sphinx was brought to the Ancient Greeks during the Bronze Age, the Greeks gave it a backstory, incorporating it into their own mythology.

In the Theogony, the Greek poet Hesiod wrote about the origins of the sphinx, which he called Phix. According to him, she is the child of Echidna and Orthrus, two monsters in Greek mythology, although some versions say Echidna’s daughter Chimaera is Phix’s mother. Echidna and Orthrus are themselves bi-natured: Echidna is half-woman, half-snake, and her son and lover Orthrus is a two-headed dog. If that sounds familiar, it’s probably because of Orthrus’ better known brother Cerberus, the guard of Hades. Born of monsters, Phix was a terrible force of destruction and bad luck.

The word “sphinx” comes from ancient Greek, from the word “sphingein,” meaning binding or squeezing, which would go on to become the lasting name of this incredible monster. And while Egyptian sphinxes were almost always depicted with a man’s head and torso, which Hesiod referred to as an “androsphinx,” Greek sphinxes had a woman’s body and torso. In Greece, too, the sphinx loses its Egyptian benevolence, becoming instead a malevolent force. While the Egyptian sphinx may have been trusted to guide one into the underworld [mention underworld above], the Greek sphinx becomes a pathway only to peril.

Riddles of the sphinx

Phix’s claim to fame is her guest appearance in the story of Oedipus, best known from Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. In some stories, Hera sent Phix to Thebes as punishment for King Laius’ sins, while in others, Apollo sent the sphinx to avenge the king’s murder. But regardless of how the sphinx got there, it was soon wreaking havoc on the city, devouring anyone who could not answer her riddle: “What goes on four feet in the morning, two feet at noon, and three feet in the evening?”

Arriving in Thebes after unwittingly killing his father, Oedipus is able to correctly outwit Phix by solving her riddle. His answer: Man, who crawls as a baby, walks as an adult, and uses a cane in old age. Ever the drama queen, she flings herself to her death. Oedipus saves the city, but dooms himself by winning Queen Jocasta’s hand in marriage and setting in motion his terrible fate of killing his father and bedding his mother.

The sphinx is a foil to Oedipus: Phix is herself a product of the same incest that Oedipus goes on to commit, an inescapable symbol of its oncoming fate. Poets like Mural Rukeyser put their own twists on the Oedipal story, with the sphinx revealing to Oedipus later in life that the reason he failed to recognize his own mother is because he failed to include women in his fateful answer to the riddle.

Through the Levant and down the Silk Road

From Egypt and Greece, the sphinx traveled the world, becoming famous from Mesopotamia to India to Thailand. Stories of the sphinx were traded alongside the goods that moved down the Silk Road. And while the sphinx was transformed in each place, its chimeral nature was, ironically, unchanging. The sphinx also repeatedly appeared as one form of guardian or another, often placed as talismans at the entrances of temples, to ward off bad luck and evil spirits.

In Sanskrit, the sphinx was known as “purushamriga” (“human-beast), and Indian sculptors created statues just as fearsome as their Egyptian and Greek counterparts. Myanmar and Thailand also have their versions of the sphinx, known respectively as manussiha and apsonsi (seen above in Bangkok). According to Ancient Origins, the Asian sphinxes were born as Hellenistic culture traveled ancient trade routes.

Every version of the sphinx finds itself inextricably linked to the fantastic and the divine. Like the Egyptian sphinx, the Asian sphinx was mostly benevolent, though it would be a mistake to underestimate its power. Like their Western counterparts, too, Asian sphinxes are shrouded in ambiguity and mystery. Few texts survive to explain the meaning and the mystery of these ominous creatures, leaving archaeologists to speculate endlessly over their remains.

How the sphinx enchanted Europeans

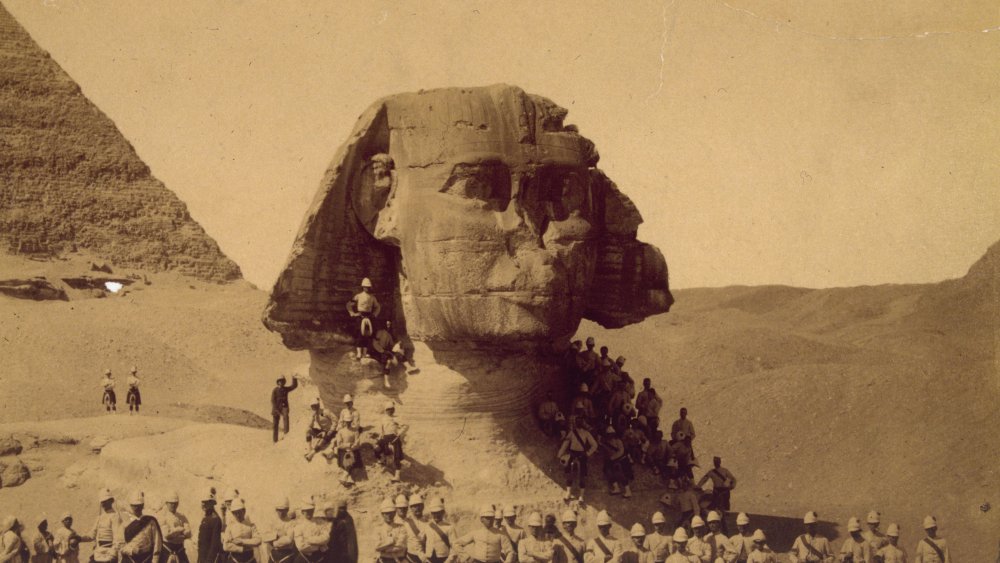

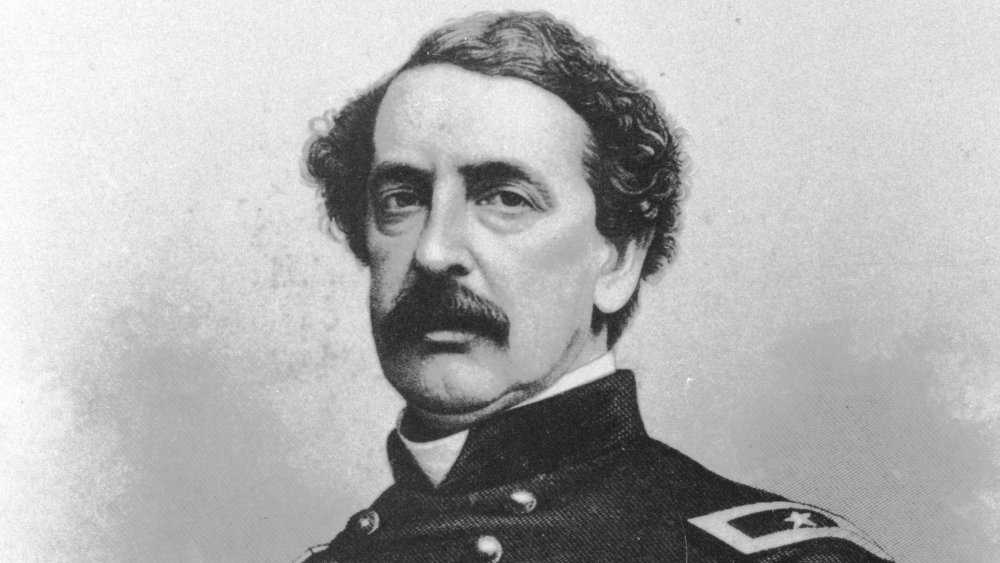

The magnificent mystery of the sphinx would infiltrate Europe, too, especially after Napoleon’s campaign into Egypt. As early as the Renaissance, the rediscovery of Greco-Roman writing inspired a surge in European curiosity about Ancient Egypt, but in the late 18th and early 19th century, this interest was magnified into a frenzy known as Egyptomania. Artists scrambled to Egypt to paint and photograph the domineering creature in the desert sands: one of the earliest photographs was taken in 1865 by Felix Bonfils, according to the Guardian. The sphinx bewitched writers, too, with W.B. Yeats penning one of the most well-known descriptions of the lumbering beast in his poem “The Second Coming.”

Outside of Egyptomania, the sphinx also invaded the European imagination through the Oedipus myth. In 1864, the artist Gustave Moreau painted “Oedipus and the Sphinx,” where a feminine sphinx captivates Oedipus with her eternal stare. The two characters are coupled, their duality unavoidable as they mirror one another in a moment of calm before the storm.

Maybe surprisingly, Sigmund Freud was one of the few who avoided the sphinx’s alluring gaze. His formulation of the Oedipus complex omits any mention of the sphinx or its riddle. One would think that one of the story’s most mystifying scenes would be of great interest to a psychoanalyst but alas, Freud responded to the sphinx’s riddle with his own: of silence.

The mysteries of the sphinx

The sphinx motif was taken up by those intrigued by mystery and magic. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the Freemasons were notoriously obsessed with Egyptian imagery. The secrecy of the sphinx echoed their own clandestine nature. Their iconography is sprinkled with countless pyramids and references to the Egyptian eye of Ra or the “all-seeing eye.” Not to say that the Freemasons weren’t creative in their extravagances, but they did know what they liked.

In the late Victorian era, the famous English occultist Aleister Crowley was also intrigued by the sphinx, writing in Liber Aleph (De Natura) of the sphinx’s wholeness and simultaneous fragmentation, an intermingling of the feminine and the masculine. There, the sphinx becomes a symbol of that which cannot be signified. According to Willis Goth Regier in Book of the Sphinx, the French symbolist Alfred Jerry, who lived at the same time as Crowley, was also fascinated by the sphinx. He ascribed similar combinations of the masculine and the feminine to it, alongside a silence that threatens but never reveals. Through its many faces, the sphinx was understood as defying the seemingly inviolable laws of nature, making it a menacing riddle of uncertainty.

How the sphinx was linked to the feminine

The sphinx became a favorite symbol for writers and artists since in its ambiguity it could signify practically anything. The sphinx was picked up as an abstraction on the feminine: dominating and at times treacherous, a manifestation of the hybrid and the paradoxical.

According to The London List, the sphinx was an especially powerful image for Argentinian Surrealist painter Leonor Fini. In most of her paintings, the sphinx appeared as a representation of the dominant feminine. Franz von Stuck was also drawn to the allure of the sphinx, immortalizing her embrace in his 1895 painting “The Sphinx’s Kiss.” For him, the sphinx becomes lust incarnate, tempting man toward the unknown.

In his novel Nadja, published in 1928, André Breton repeatedly compares the titular character to a sphinx. Her mystery drives the narrator crazy until he begins to learn more about her, at which point he loses interest. Typical. Breton even begins his novel with the question “Who am I?”, echoing the Oedipal question of identity and self-knowing. Oscar Wilde, never one to be left out of literary investigations, invokes a femme fatale version of the sphinx, where female sexuality is to be banished.

And unlike the willfully oblivious Freud, Carl Jung recognized the significance of such a mysterious signifier, proclaiming the sphinx as an archetype of the “mother-imago,” or Terrible Mother. He compares the sphinx’s riddling to the seductive nature of women, whose animality is feared by men who seek cohesion and comprehension.

The sphinx as a symbol for the symbolic

Philosophers were also obsessed with the imagery of the sphinx and took it to the limits of interpretation and back. The German philosopher Hegel underlined the ambiguity of the creature by calling it a “symbol for the symbolic.” The sphinx solidifies itself as a sign for the indecipherable, a trope that has seemingly followed it from its inception. And Hegel pretty much nails it in his description, since everyone picks for themselves what they want the sphinx to mean.

But for Hegel, the sphinx was something to be defeated: It was man’s grotesque unconscious, redeemable only by the conscious. In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche also took up the image of the sphinx as both truth and the desire for truth. He gives man the ability to preach riddling truth, just as the sphinx did. And in typical Nietzschean fashion, he encourages the reader to be both Oedipus and sphinx, as the sphinx embodied the contradictory oneness that can be found in Nietzsche’s countless paradoxes.

Sphinxes in contemporary culture

The sphinx continues to captivate people, whether as an echo of their former mythology or in new forms. Per the Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual, sphinxes, like their ancestors, are monsters that guard entranceways, though in this modern capitalist world, they can be seen accepting payments for their help on particularly tricky riddles.

The Neverending Story by Michael Ende also contains a timeless description of two sphinxes who guard the first gate to the Southern Oracle, appropriately called the Riddle Gate. These sphinxes stare stonily ahead, eyes locked with one another, as they share the riddles of the universe back and forth. The movie version gets especially wild, with the sphinxes basically shooting lasers out of their eyes to destroy anyone unworthy who tries to pass.

Though its form may change, the sphinx is always a protector, associated with mysterious knowledge. While the frenzy for the sphinx has died down since 19th-century Egyptomania, the impenetrable gaze of the sphinx continues to mystify and intrigue. Sphinxes lend their names to cats and moths and even software documentation programs. The riddle of the sphinx has become an interest in its enduring appeal, a fascination that holds fast despite, or perhaps because of, its inscrutability.

The Truth About Canada And Denmark's Fight For Hans Island

Jokes That Predicted The Future

What Being An Ancient Egyptian Embalmer Was Really Like

The Creepiest Tales Of Island Ghosts

The Bizarre Way Your Character Could Die In Killer Instinct

The Truth About The Exorcism Of Anna Ecklund

What We Know About The 'Ghost Population' Of Missing Humans

Sloped Toilet Designed To Shorten Workplace Bathroom Breaks

University Of Phoenix Agrees To Cancel $141 Million Of Student Loan Debt

The Bizarre True Story Of Bigfoot, America's Missing Ape