What Being An Ancient Egyptian Embalmer Was Really Like

Ancient Egypt is popularly known for its pyramids, the Nile, and of course its mummies. These linen-bandaged cadavers have entered popular culture as a gothic Macguffin, starring in such films as 1932’s The Mummy with Boris Karloff to 1955’s Abbot and Costello Meet the Mummy or more recently 1999’s The Mummy. Yet mummies were neither a fantasy nor a plot device to the ancient Egyptians. They were essential spiritual vehicles. That is why the embalmers of Egyptian mummies loom large in that civilization.

Yet little has been known about embalmers or their work. However, recent discoveries and research have shed new light on this most curious of professions. Embalmers were priests, part time funeral directors, and definitely full time proto capitalists. Thousands of years before Adam Smith, they knew that every time they wrapped up a mummy, the demand for their services was not just inelastic but eternal.

Death is temporary, Ka is forever

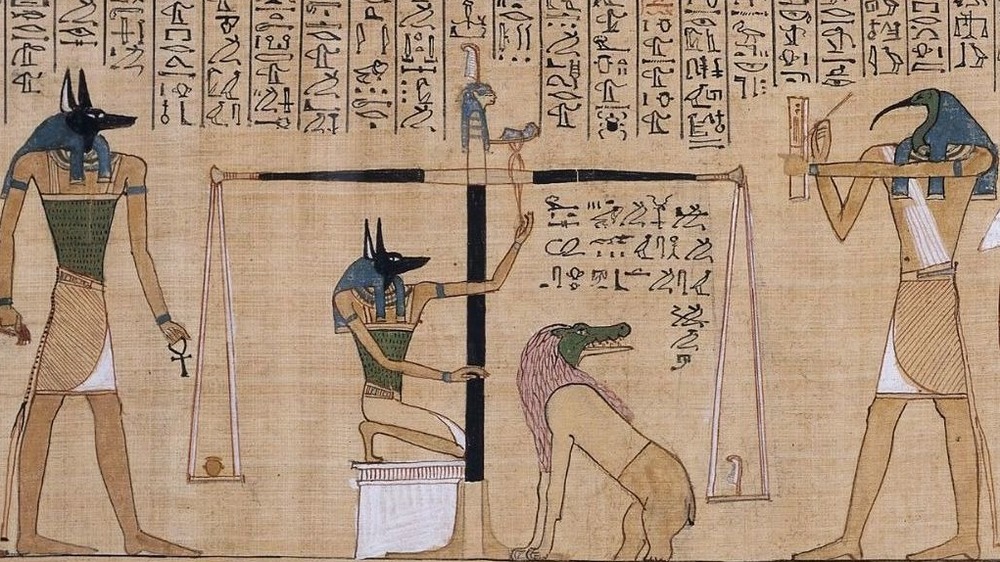

To understand what life was like for an ancient Egyptian embalmer, you need to know about Egyptian religious beliefs. According to the Dallas Museum of Art, Egyptians believed that a person needed to live in harmony with the cosmic order, called maat. After a person died, they were judged by Osiris, the Egyptian god of the dead. A person’s heart was weighed against a feather. If one’s heart was lighter than the feather, the soul, or universal spirit one received at birth called ka, would pass on to an afterlife in the Field of Reeds. If one’s heart was too heavy… they’d be devoured by Ammit, a crocodile-shaped goddess.

The Field of Reeds was a mirror image of the physical world. Ka was not an ethereal thing. It was intertwined with the physical body. Both were needed to pass into the Field of Reeds. According to Egyptologist Rita Lucarelli from the University of California, Berkeley, who was interviewed by LiveScience, “The ancient Egyptians were obsessed with the afterlife. They believed that there is another life after the life here on Earth.” This was modeled on the myth of the rebirth of the god Osiris. Thus, the idea of embalming, or preserving the dead body through mummification, was born.

Embalmers got into business after pharaohs were entombed

Mummification started by accident. The arid Egyptian environment is very conducive to mummification. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the first Egyptian mummies were bodies probably dried out in graves dug in the sand through natural processes. The resulting well-preserved bodies were an inspiring if not direct sign from the gods that this is how the dead should be treated. As society developed, the Egyptians began to place the bodies of their rulers within sarcophagi in tombs. However, bodies do not preserve as well in tombs as they did in dry desert sands. It is at this point that embalmers began to develop the techniques they needed to mummify the dead. By about 2600 B.C., Egyptians probably started to embalm the dead on purpose. According to National Geographic, this started with royalty. This practice continued for over two millennia.

The pharaohs of Egypt were considered to be divinely appointed and acted as the intermediary of the gods. For the embalmers, this meant that their work was a sacred act, and being an embalmer associated them with the priesthood and granted them high status.

How embalmers gave a corpse the royal treatment

The exact details of how Egyptian embalmers mummified the dead is a trade secret that is still being pieced together by archaeologists. There are no existing Egyptian technical manuals on the subject, but the ancient Greeks wrote about it. The first account is by Herodotus, who wrote about embalmers in 430 B.C. in his Histories.

Embalmers first needed to remove the internal organs, which easily decayed. According to National Geographic, the process began by taking the body to a temporary building called a ibw. The embalmers took an iron hook, inserted it up the cadaver’s nostril, and penetrated the brain cavity. A good embalmer tried very hard not to break the body’s nose, though sometimes it was unavoidable. Once done, the hook was used to swirl around the grey matter and extract it. The brain bits were discarded, since the Egyptians thought the brain useless. To the Egyptians, the heart was the source of a person’s individuality — their intelligence, wisdom, and personality were all in the heart not in the head.

Cutting and evisceration

According to Grafton Elliot Smith and Warren R. Dawson‘s classic account of embalming, after the brain was tossed out, work on the body proper began. A scribe marked where to cut an opening on the corpse’s side. Cutters, or slitters, did this work with an obsidian knife. Then reaching through the opening, the lungs, liver, intestines, and all other organs except the kidneys and the heart were removed.

These cutters were actually not embalmers, since the work they did was considered desecration. They were of much lower status, and after they finished their work, they fled the scene having objects and curses hurled at them as a matter of ceremony.

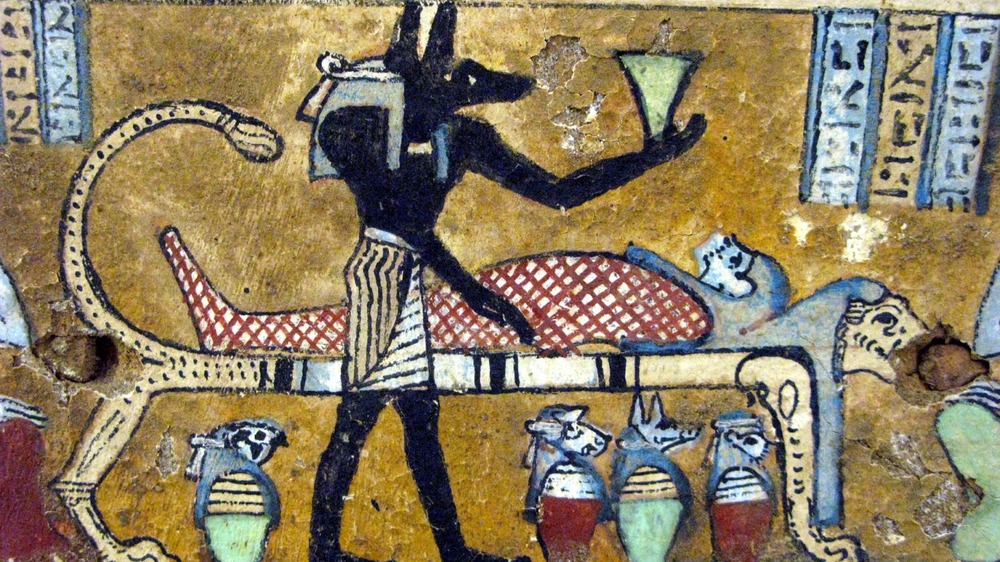

The embalmers then began the preservation process. They removed the remaining organs and cleared out the body cavity. They washed the body out with substances including palm wine. Then in order to counter any odor from putrefaction, they applied liberal amounts of aromatics such as myrrh and cinnamon. Meanwhile, organs that had been removed were washed with palm wine and placed into canopic jars for preservation. When all was done, the heart was placed back inside the body. The dead needed their hearts for when Osiris judged them. In later years, the heart was replaced with a scarab, symbolizing the god Osiris’s rebirth. The kidneys were most likely left inside the body, being considered unimportant.

Seventy days

The mummy-to-be was removed to a per nefer, meaning “house of beauty.” To dry the corpse, the embalmers used natron, a form of naturally occurring salt that the Egyptians harvested from lake beds. Embalmers buried the body with natron, as well as inserting packets of it inside the body cavity. The corpse sat ideally for 40 days. When the time was up, the embalmers took the body, washed it, and removed the packets. The resulting body was dried out but otherwise recognizable. To improve its appearance, in some instances the embalmers filled the inside with rags or straw to puff out sunken areas. They even added false eyes — sometimes using onions. Their work impressed the deceased’s kin. The Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus, remarked, “every member of [the body] having been so preserved intact that even the hair on the eyelids and brows remains, the entire appearance of the body is unchanged, and the cast of its shape is recognizable.”

The embalmers then entered the last stage of the work, spending some 30 days dressing the body. They applied sticky resin to the body and wrapped it with hundreds of yards of linen bandages. At points they stopped either to insert a protective amulet there or recite a chant there. Then after over two months of work… Voila! The mummy was complete. All that was left was the “Opening of the Mouth Ceremony” in which the mummy was placed into a standing position and symbolically reanimated for the afterlife.

Mummies for the masses!

Embalmers originally treated only Egyptian royalty. According to National Geographic, there was only one team of embalmers for the royal family and those who the pharaoh deemed worthy of mummification. However, when the Old Kingdom gave way to the Middle Kingdom (1938-1630 B.C.), embalming started to extend to the population at large. Independent and entrepreneurial embalmers set up workshops and acted as the physical connection between the realms of the living and the dead.

Embalming reached its peak as an art and science during the New Kingdom (1552-1069 B.C.), however embalming continued for centuries after. Throughout this period, embalmers would modify their recipes and ingredients, but in general, the mummification process remained the same.

The embalming business grew into one of Egypt’s most thriving industries. Salima Ikram, an Egyptologist at the American University in Cairo, was interviewed by Nova and asked how many mummies were there. She replied, “Some people estimate 70 million mummies, but I think that’s an underestimate. Mummification was carried out in Egypt… for over 3,000 years. I’m sure more human mummies were made during this time period.”

While mummification had moved to the masses, not all mummies were created equally.

Embalmers, incorporated

Embalmers were among the higher status holders in society. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus noted that embalmers were “considered worthy of every honour and consideration, associating with the priests and even coming and going in the temples without hindrance, as being undefiled.”

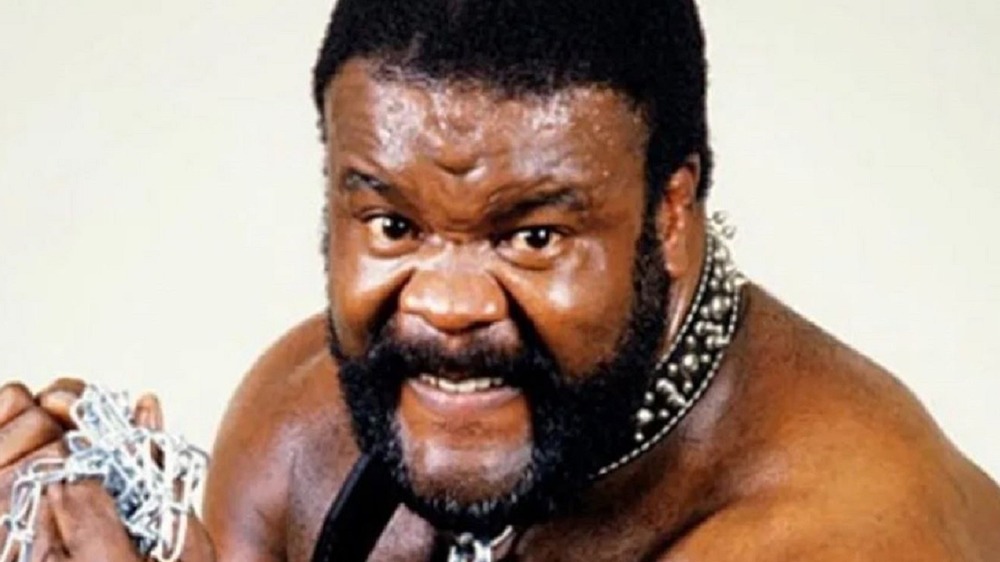

Siculus, however, did not differentiate between different kinds of embalmers, each of which had different statuses. According to Jim Pipe in his Egyptian Mummies: A Very Peculiar History, the most revered embalmer was the hery-seshta, who oversaw the entire process. He stood in for the god Anubis, the jackal-headed god of death and mummification. The hery-seshta even wore a dog mask to set an appropriate tone. Below him was his assistant, the hetemu-netjer. Spells and prayers were recited by the hery-heb. Those who did the bandaging were wetyu. The scribe who marked the body for incision was the sesh. Those who did the cutting, and subsequently driven off, were the parascites.

While there was no known guild for embalmers, the trade was passed along through the generations. These set up workshops to perform the embalming rituals in necropolises, cities of the dead. One of the most significant sites is the necropolis at Saqqara. The site was used as an Egyptian burial ground for millennia — which was plenty of time for embalmers to establish a flourishing industry.

An Egyptian embalmer's workshop

A recent discovery at Saqqara was reported by National Geographic, which shows just how business-savvy these embalmers were. In 2018, field archaeologists found what was purported to be history’s first funeral home deep underground in long ignored shafts. After two years of excavation, archaeologists found a workshop dated to approximately 600 B.C. It sported a raised table, drainage channels for blood, and sensible ventilation shafts. Ramadan Hussein, one of the chief Egyptologists working the site said to National Geographic, “If you’re doing evisceration down there, you need air moving in to get rid of insects. You want constant movement of air when you’re dealing with cadavers.”

If there was a worry about the smell, the very large incense burner could furnish enough aroma to overpower any whiff of putrefaction. What is more, the archaeologists found considerable amounts of pottery shards, as well as oils that were used in the embalming process. When reconstructed, Egyptologists saw that these were labeled with ingredients and instructions that provided clues as to what ingredients the embalmers were using to prepare the mummies. Hussein said, “For the first time, we can talk about the archaeology of embalming.”

All of this adds to our knowledge of ancient Egyptian society. Where there is written and even artistic evidence of embalming, there has been little archaeological evidence hitherto. Much of this new work is presented in National Geographic’s new series, Kingdom of the Mummies.

Embalmers had a flexible business model

While Egyptian royalty and the richest in society could afford the full embalming treatment, those of lesser means needed to find a more middling vehicle to pass into the afterlife. This was no problem for the embalmers who offered a menu of options that a dead person’s relations could choose from.

The process started with the deceased’s next of kin being presented with model mummies, each of different quality. The bereaved needed to select a tasteful, yet affordable plan. Herodotus named three basic plans. There was the full royal treatment as described earlier. Then there was the middle-class treatment, which consisted of injecting cedar oil into the body cavity with natron. This apparently dissolved the organs, which were then purged. A low-income person could resort to a simple purge followed by the natron treatment before the body was returned to his or her kin.

Herodotus’s account holds up to archaeological findings. As reported by the Guardian, Ramadan Hussein stated, “There are clear socioeconomic differences between the mummies in the shaft. We see that mummification happened above ground, while some of those buried down there were either buried in private or shared chambers.”

According to National Geographic, the embalmers also provided ongoing services in a priestly capacity, such as caring for the soul of the deceased. Literally, hundreds of bodies could be housed within their tombs. The family of the deceased was responsible for bringing cash donations to keep their lost kin in good graces.

Embalmers also mummified millions of animals

Embalmers also had a flourishing business mummifying animals. Since the afterlife was considered to be just like the living world, Egyptians expected to have all the necessary accoutrements for a rewarding post-life. According to an article in the journal Nature, this included having animals for food, animals to sacrifice to or honor the gods, and animals to have as pets. Cats, ibis, crocodiles, dogs, hawks, and snakes are all animals that embalmers mummified.

According to Egyptologist Salima Ikram, one section of the Saqqara necropolis has an estimated 8 million mummified dogs and 4 million ibises in a neighboring area. These were not pets but considered votive offerings to Anubis (the dogs) and Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom. It is not clear if the embalmers themselves were engaged in the procurement of these animals or just embalming them. Still, the authors of the Nature article noted there was money to be made — “The animal mummification ‘industry’ required high production volumes, necessitating significant infrastructure, resources, and staffing of farms that reared animals for mummification and subsequent sale. Dedicated keepers were employed to breed the animals, while other animals were imported or gathered from the wild. Temple priests killed and embalmed the animals so they were made suitable as offerings to the gods.”

An eternal business ends

While Ka may last forever, the embalming business in Egypt did not. It is unclear as to exactly when embalming died as a practice, but it is certainly connected to the rise of Christianity, reports PBS. As Egyptians converted to Christianity between the fourth and seventh centuries A.D., demand for mummification dwindled. Still it is worth noting that early Christians in Egypt did accept mummification to some degree until it faded away. However, embalming has made some sort of comeback as deceased popes have been commonly embalmed in recent history.

The embalming craft of ancient Egypt became lost to history and is now being pieced together by archaeologists. In the embalmers 3,000-year history, it is estimated that they created at least 70 million mummies, not to mention embalmed millions of animals. If so many mummies were made, you may wonder what happened to them all? The answer is perhaps even more macabre than the process embalmers used to make mummies in the first place.

Got mummy?

Sadly, most of the legacy of ancient Egypt’s embalmers has been lost to posterity due to cannibalism and Victorian-era gothic parties. According to Richard Sugg, author of Mummies, Cannibals, and Vampires, mummies were taken from their tombs for use as medicine over the centuries. The remains, called mumia, refers to the bitumen with which some mummies were believed to have been treated with. Mumia was used to treat as many ailments as snake oil. An article by Medical News Today examined an 18th century medical treatise that lists mummy for use as a blood thinner, cough suppressant, pain killer, and women’s menstrual aid.

There were also rumors that mummies had been used for fuel for steam locomotives and fertilizer. Neither of these seem to have a basis in fact. However, what is true is that mummy remains were used as a paint pigment, and British Victorians held mummy unwrapping parties. The trend actually started in 1698 with the French consul in Cairo, but by the 19th century, British Victorians were wild for unwrapping mummies. These public dissections actually humanized the ancient Egyptians for many people and provided knowledge on how they were individuals. Ultimately, however, it was the embalmers who knew their clients intimately, who they transported to the Field of Reeds.

The Surprising Reason Rotting Teeth Was Once A Sign Of Wealth

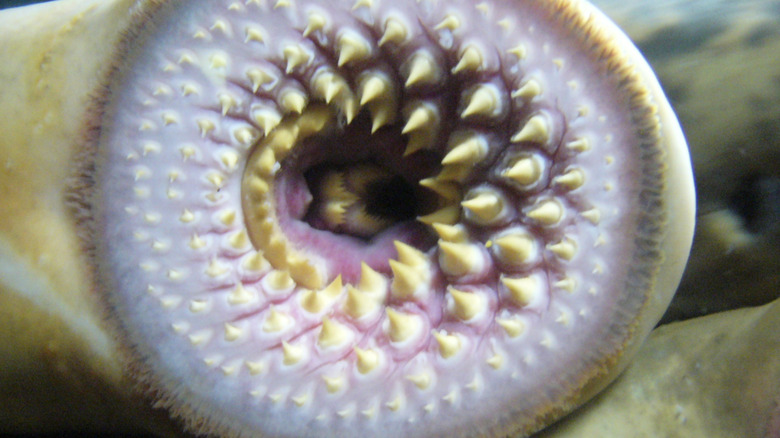

The Hideous Fish That Was Said To Be The Cause Of Henry I's Death

The Mysterious Death Of The Man Known As Peter Bergmann

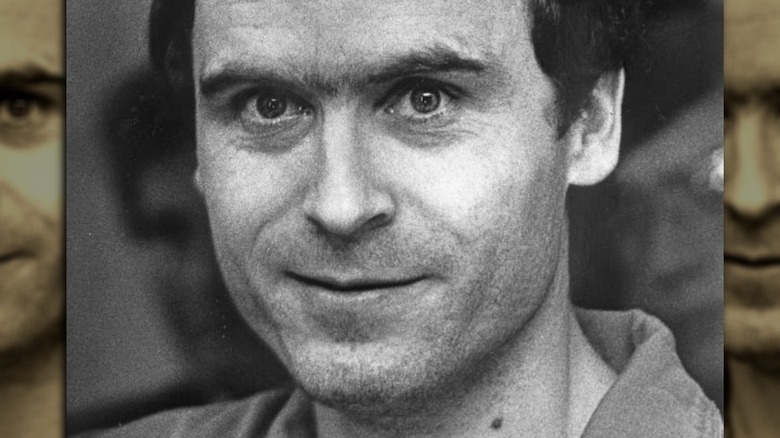

Here's What Happened To The Bodies Of These Serial Killers

Astronomers Detect Biggest Known Explosion In The Universe

Antarctica Just Recorded Its Hottest Temperature Ever

Scientists Turned Their Own Frozen Poop Into Knives

Frozen LEGOs May Change Quantum Computing

The Weirdest Things Spotted On Google Earth

The One Place In The US That Google Earth Didn't Update For Years