The Mythology Of Artemis Explained

When it comes to the gods and goddesses of the ancient pantheons, not all were created equal. Some were to be feared more than worshipped, but when it came to favorites, Artemis was definitely up there.

Britannica says that she was incredibly popular, especially among the rural and agricultural sections of the Greek empire. That’s not entirely surprising — her domain was the wilderness, where she reigned as the goddess of the hunt, protector of animals, and overseer of wild growth. From vast meadows to streams, lakes, and mountains, she preferred running with her animals and dancing with nymphs to hanging out with the other Olympians. With her family, that’s pretty understandable.

As explained by ThoughtCo, Artemis was often depicted alongside either a dog or a stag, and was almost always holding a bow and arrows. Homeric hymns referred to her as Artemis Iokheaira — who delights in arrows — and she definitely wasn’t afraid to use them.

While some of her fellow Olympians — like her father, Zeus — made it a point to get as many notches on his divine bedpost as possible, Artemis was never married. As the virgin goddess, she became known as the protector of women and girls — particularly those facing the harrowing experience that was childbirth.

Those are the basics, but there’s a lot more to this beloved goddess of the wild.

Artemis had a much older form, and was adopted by the Greeks

Artemis might be most famously known as one of the 12 Olympians, but she’s much older than that. According to Livius, she was originally called Artimus, and her worship went back to an area in what’s now western Turkey. She was one of the mother goddesses, and while it’s not clear just when her cult developed, she had a massive temple in Lydia by 560 B.C.

She also has connections to ancient Persia and Babylonia, and copies of some of her ancient statues are still around (although many of the originals are long gone). She also looked a little different. While the Greeks portrayed her as a young girl, this pre-Greek Artimus was more mature. Statues show her wearing a zodiac symbol around her neck and a dress covered with images of animals, while her chest and stomach are covered with what looks a little like a series of egg sacks. Scholars are still arguing exactly what they’re meant to represent.

Like her Greek counterpart, she was connected to fertility and the protection of women in childbirth. It’s been suggested that she’s covered in female breasts, but most historians now think that’s completely wrong. Two popular theories suggest they’re either gourds — ancient symbols of fertility — or bull testicles. ThoughtCo says that the sacks could be a reference to the bulls regularly sacrificed in her honor.

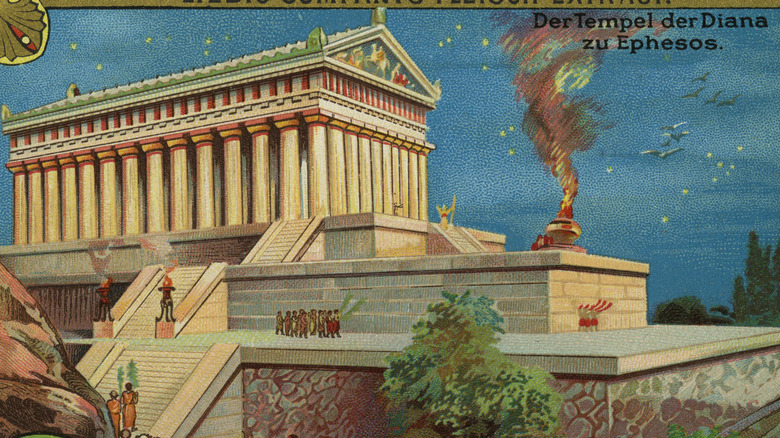

Her temple burned while she was at the birth of one of history's greatest warriors

According to the University of Warwick, it’s not clear just how long Ephesus was dedicated to the worship of Artemis, but a first temple was destroyed at some point during the 7th century B.C.

It was rebuilt again around 560 B.C., and in 356 B.C., it was burned by Herostratus in the hopes of cementing his place in history. (It didn’t really work — a decree from the Ephesians forbid recording his name, which only existed in a work by Strabo.) Explaining how that happened could be a tricky, but it was said that Artemis had left her temple to attend the birth of Alexander the Great.

He didn’t forget, either. When Alexander took control of Ephesus, he offered to fund the rebuilding of her temple. His offer was refused: the Ephesians responded “it was inappropriate for a god to dedicate offerings to gods.”

The temple honored the goddess’s birthplace, and it was nothing short of awe-inspiring. It would become one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, and Antipater of Sindon wrote (via the University of Chicago): “I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon … the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus, and the hanging gardens, and the colossus of the Sun, and the huge labor of the high pyramids … but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy …”

Ruins of the temple still remain in Ephesus.

Artemis took her position in the pantheon the moment she was born

Artemis is the twin sister of Apollo, and their mother was Leto, according to Theoi. Leto was one of the Titans, but it’s unclear what her role in the pantheon was. It’s been suggested she was the embodiment of motherhood, and that she may have also been connected with decorum and modesty, or the night, or — weirdly — the day.

There are a few different versions to the tale, but the basics tend to stay the same. Leto was one of the Zeus’s lovers, and according to the story, he actually loved her, which sent his wife, Hera, into a rage. Hera sent their son Ares to make sure the pregnant Leto could never rest, and it was only when Zeus turned Leto into a quail that she made her way to Delos. It was there that she gave birth first to Artemis — who, according to Homer, was carried and birthed completely pain-free, after nine days of agony inflicted by Hera and Ares.

Then, Leto delivered Apollo, cementing her association with childbirth and delivery.

Zeus has a ton of children who aren’t among the Olympians, and the position of Artemis and Apollo is thanks to Leto. Homer recounted that after the twins’ birth, the three of them headed to Mount Olympus, where Leto strolled with her children, hung their weapons up, and told them to take their rightful place as children of a god.

The wishes of a child goddess

According to Homer (via Theoi), Hera didn’t have much of a choice but to allow her husband’s children into Olympus. Artemis was just a child when Zeus told her, “When goddesses bear me children like this, little need I heed the wrath of jealous Hera.”

When she was young, Artemis asked her father for a series of gifts. The first was to always remain a virgin, and the second was to never fight or argue with her brother.

Then, she asked for a short tunic that would allow her to run and hunt, 60 young attendants, and a further 20 handmaidens who would hunt with her and care for her dogs. When it came time to choose a patron city, she told him it didn’t matter — she would prefer, instead, the mountains, and said that she would only visit a city when a woman in the pains of childbirth needed her.

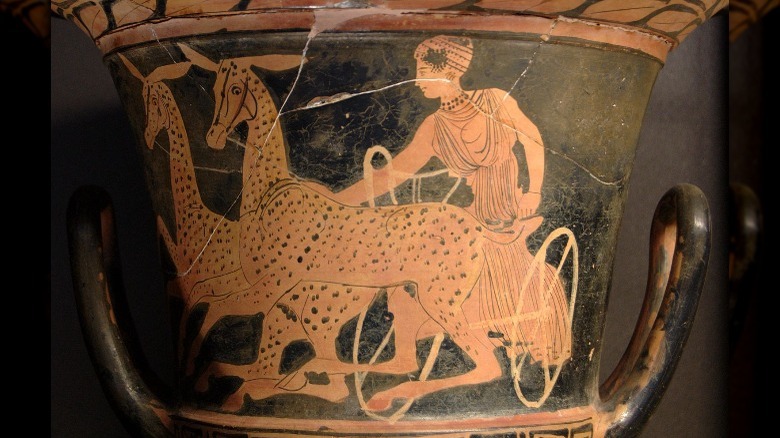

Pan gave her dogs — two black and white, three red, one with spots, and seven females so fast they could catch anything. The other things she was known for, she got herself. Callimachus’s Hymn to Artemis tells how Artemis went straight to the Kyklopes to ask them to make her a bow with arrows for her quiver. And finally, she tracked and captured golden-horned deer to pull her chariot.

Artemis was always her mother's protector

Theoi says that when Leto shows up in Greek art, she’s usually pictured with her children. Both Artemis and Apollo were fiercely protective of her, and would absolutely kill to right a wrong against her, no matter how slight.

Niobe was the Queen of Thebes, and according to the tale told by Ovid (via ThoughtCo), she made a major mistake when she was told that her people should probably pay homage to Leto and her children. Niobe scoffed at the idea, saying that the people of Thebes shouldn’t worship a woman who had only two children, that they should worship her as queen and granddaughter of Zeus and Atlas, and a mother of 14.

There are two versions of what happens after Leto finds out about this and tells her children, and neither work out for Niobe. In one, Apollo gets revenge by shooting all the sons with arrows carrying a plague, which sweeps through the whole family. In the more widely told tale, Apollo kills all her sons, while Artemis kills all her daughters. Niobe is turned to stone, and the people of Thebes know to not only honor Artemis and Apollo, but Leto as well.

One of her myths contributed to numerous Renaissance works

The Greek myths provided some rich source materials for artists throughout the Renaissance, and according to History Today, the story of Artemis (who was known as Diana in Rome) and Actaeon was one of the most popular — so popular that when it was painted by the master Titian, it became one of the most well-known and highly regarded works of the era.

As with many myths, there are a few different versions of the story. The one painted by Titian (pictured) is from the version retold by Ovid in Metamorphoses. Actaeon — exhausted from the day’s hunt — has sent his men away and wanders into the forest for some good old R&R. Fate had something else in mind, and he stumbles right into a pool where Artemis and her nymphs are bathing. Everyone’s as naked as the day they were born, and even as her nymphs scramble to hide Artemis and preserve her modesty, it’s too late.

Artemis throws water in Actaeon’s face and promises that if he can, he can tell everyone that he’s seen her naked. He immediately starts to change, turning into a stag just like the ones he was just hunting. That’s when his dogs catch the scent of their prey.

He runs, but not fast enough: His dogs give chase and catch him, tearing him to pieces for his accidental crime against the virgin huntress.

Artemis and Orion: Friends or frenemies?

Orion is one of the easiest constellations to find in the night sky, and it’s not a coincidence that NASA‘s Artemis I mission involves a spacecraft named Orion.

Strangely, there’s two different versions of the Artemis-Orion myth, and they couldn’t be more different.

Theoi explains that Orion and Artemis were the best of friends, hunting together and generally just hanging out until things went sideways. In one myth, Gaia (the Earth) gets mad at them, because Orion either threatens to kill everything on the planet, or says that he’s capable of it. She sends a massive scorpion to kill him, and Artemis secures him a place among the stars of the night sky. In another version, Apollo gets insanely jealous that his sister has a best friend that isn’t him, and tricks her into killing Orion during an archery contest. Again, she mourns him and gives him a place among the stars.

Other stories (via Theoi) are a little less kind to Orion. Some claim he died after challenging Artemis to a discus throw, while others claim he attempted to assault either the goddess herself or one of her virgin attendants. Stories where she kills him often take a strange stance, calling her things like “the cruel virgin.”

No, Artemis is not anti-man

One of Artemis’ key characteristics is her perpetual virginity, but even though any man who threatens that usually pays with his life, to say she’s anti-man is not only incorrect, but doing her a disservice.

Theoi reports that Homeric hymns say that there are only three deities that are immune to Aphrodite’s ability to stir up love and lust: Artemis, Zeus, and Athena. But men are among those who receive Artemis’ divine favor. Hippolytos, for example, was a prince and devotee of Artemis. When he was killed by Theseus on orders from Aphrodite, Artemis intervened and convinced Asklepios to raise him from the dead. Hippolytos returned to become king and dedicated a section of his land to the goddess, while Zeus killed Asklepios for his actions.

Artemis also intervened with her brother on behalf of a Babylonian king, Klinis. Klinis mistakenly thought Apollo would like a donkey sacrifice, and when Apollo made it clear that wasn’t cool, his priests didn’t stop the sacrifice in spite of Klinis’ instructions. Apollo drove the donkeys mad, and when they started eating everyone in sight, Artemis turned the king into an eagle to save him from the man-eating donkeys.

Research done via the University of Birmingham found that Artemis was considered as important to all children, and was seen as a guide that helped boys on their path to manhood. Boys undertaking a rite of passage would appeal to Artemis, and it was believed she would help guide them on their way to being warriors and fathers.

Artemis vs. Herakles

Artemis shows up three times on Herakles’ journey to undertake his 12 Labors, and in one, she was almost the end of him.

His third labor was to capture the Hind of Ceryneia, which basically means that Eurystheus wanted him to capture the golden-horned, bronze-hoofed deer that was sacred to Artemis. According to the Perseus Project, Herakles stalked the deer for a year before shooting and wounding it as it was about to escape across the river. That’s when Artemis showed up; in spite of her rage, though, she allowed Herakles to explain. Once she understood what was going on, she healed the deer and let her half-brother take the hind to Mycenae and fulfil the conditions of his labor.

Some stories also connect her to two other of the 12 labors. In Homer’s Odyssey (via Theoi), it’s said that the rampaging Erymanthian Boar was actually another of her sacred animals. Pausanias writes that the Stymphalian birds were also sacred to her, and the site of the labor was the temple of Stymphalian Artemis.

The Trojan War and her defeat in combat… twice

The Trojan War is one of the most famous episodes in Greek mythology, and Artemis was in the middle of it right from the beginning. In the Iliad (via Theoi), she was the one that put a stop to the winds, and forced the Greeks to look into sacrificing the daughter of Agamemnon. The idea was abhorrent to Artemis. She rescued Iphigeneia and granted her immortality, then threw in solidly on the side of the Trojans.

Along with Apollo and Leto, Artemis showed up occasionally throughout the epic, usually saving one of Troy’s wounded warriors. But the Greeks had Hera, and the pretense of the conflict allowed her to settle an old score. The two goddesses went head-to-head, and it ended with Artemis getting a sound beating from her father’s long-suffering wife after being challenged: “… if you would learn what fighting is, come on. You will find out how much stronger I am when you try to match strength against me.”

That’s not the only time Artemis found herself on the receiving end of a beating from Hera, and when the gods were split into factions during the so-called Indian Wars of Dionysos, they were once again on opposing sides. And once again, Hera won. “Hera picked up a rough missile of the air, a frozen mass of hail, circled it, and struck Artemis with the jagged mass. … Artemis, smitten by the weapon of ice, emptied her quiver upon the ground.”

The Cult of the She-Bear

It’s impossible to exaggerate the importance of Artemis and her cult to the people of ancient Greece. According to Women in Antiquity, she wasn’t just the goddess of the wild and the hunt, she was the goddess of transition: between the wild and civilization, between boyhood and manhood, between a girl’s childhood, puberty, and fertility. Excavation of her shrine at Brauron in Attica suggests that she “presides over changes in the states of being.” If there’s ever a time when a person feels they need a little divine support, it’s during major life changes.

There are two myths that contribute to the worship of Artemis at Brauron (via Study). The first happens when Iphigeneia — now a priestess of Artemis — helps her brother steal a statue of the goddess. After the theft, Iphigenia set up the site at Brauron, while Orestes started another cult to Artemis. The other says that two Athenian hunters killed a bear beloved to Artemis, and in retribution, the goddess sent a plague to the city every fifth year. In order to avert the plague, Athenian girls were given to the cult of Artemis — known as the Great-She-Bear — every five years.

The site at Brauron was important to ancient Greek women. The clothing of women who died in childbirth would be taken there and given to Iphigenia, as a priestess associated with sacrifice. The clothing of women who had successful deliveries would be given to Artemis, with their thanks.

There's a theory her cult was folded into the Virgin Mary

Similarly to how Artemis was adopted by Greek mythology from an earlier incarnation, there’s a theory that she once again made the jump from an ancient religion into a newer one: Christianity, in the form of the Virgin Mary.

It’s not as far-fetched as it seems at first glance. The Universitet Metropolitan Beograd reports that evidence starts in the western Balkans. That’s where archaeologists have found evidence of a temple to Artemis being replaced with a church to the Virgin Mary.

And that’s not all. Carla Ionescu from York University argues that for generations, Artemis was such an important part of life that when her temples were razed and Christianity started gaining favor, the Virgin Mary only became such an important figure because she was standing on the shoulders of Artemis. When citizens started to lose their original Mother Goddess — particularly in Ephesus — the adoption of the Virgin Mary as significant was a way of converting the populace to Christianity, while still allowing them to keep their age-old beliefs in a sacred female watching over them as healer and virgin mother.

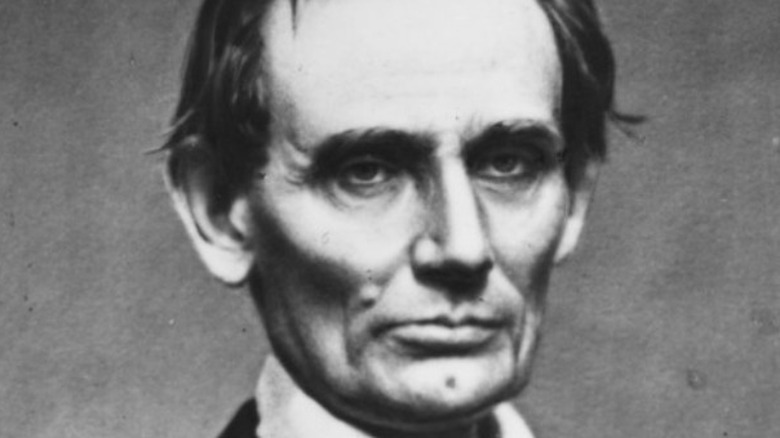

How A Lincoln Assassination Co-Conspirator Wound Up Saving Dozens Of Lives In Prison

The Crazy True Story Of Satirist Dorothy Parker

The Untold Story Of The First RVs

The Civil War Battle That Also Took Place In Yorktown

What Did The Titanic Look Like In Color?

Here's How Shakespeare's Globe Theatre Was Destroyed

This Is When Donald Harvey Killed For The First Time

This Was The Secret To Jesse Owens' Speed

Artists Who Were Ahead Of Their Time

Why The 1982 Genesis Reunion Was A Matter Of Life Or Death