The Mythology Of Odin Explained

Odin was one of the central gods in Norse mythology, and also one of the most complex. According to the World History Encyclopedia, he was not only a god of war, but a god of poetry, magic, and the dead. Odin appears in traditional Germanic mythology under the names Woden, Wodan, Wutan, and Wuotan. These Germanic spellings give us the day of the week named after him: Wednesday. He is, possibly aside from Thor, the most well-known of all the Norse gods. So what made this most fascinating figure of the Norse pantheon tick?

To understand Odin, you need to understand the Norse conception of the universe. To the Norse people, the universe was made up of three strata of nine worlds centered around and on an elemental ash tree known as Yggdrasil. The gods of the Norse pantheon interact in these worlds not with all knowing omniscience, but with lots of unknowing. This creates a certain level of complication and allegory in Norse myth — and central to that complexity is Odin.

Odin and his brothers created the world

Odin may be known as the allfather, but he had a father and grandfather of his own. As explained in “Gods, Heroes, and Kings: The Battle for Mythic Britain,” the first god was Buri, who was licked out of cosmic ice at the beginning of time by the celestial cow Audumala. Buri had a son named Bor, who married a frost-giantess named Bestla. She gave birth to Odin and his two younger brothers, Vili and Ve.

The three brothers then came into conflict with the frost giant Ymir. This creature was no mere giant but had come into being at the beginning of time in the void between the elemental fires of Muspelheim and the elemental cold of Niflheim. The brothers slew Ymir and used his body to create the world. The giant’s skull became the heavens, his bones the mountains, and his blood the waters of the world. Then, using sparks from Muspelheim, the brothers created the stars and even assigned dwarves to the four cardinal directions.

In essence, Odin and his brothers organized the universe into the nine worlds. In doing so, they made an especially fertile land in the middle of all the worlds of Norse mythology called Midgard — the world of humans — out of Ymir’s eyebrows. As a last stroke of creation, they gave life to Ask, the first man, from an ash tree and Embla, the first woman, from an elm tree.

Odin ruled the Aesir

Norse mythology had two tribes of gods: the Vanir and the Aesir. Odin ruled over the Aesir from the realm of Asgard. Odin’s principle wife was Frigg and “Norse Mythology” also lists Rind and Jord as his wives or concubines. While the World History Encyclopedia is quick to point out the god’s philandering ways are comparable to Zeus, and in the sources Odin is often portrayed as a womanizer, the wives of Odin tell more about the naturalism of Norse mythology than philandering. Each of Odin’s wives can be read as an allegory for the state of the Earth, or put another way, a form of the earth goddess Gaia.

Frigg was representative of a bountiful, cultivated Earth, Jord was the wild Earth, and Rind the Earth covered in ice and snow. The children of each one of Odin’s wives reflected this. Thor, whose mother was Jord, was a thunder god. Balder, whose mother was Frigg, was the personification of good. Vali, who was the son of the giantess Rind, was as described by Norse Mythology for Smart People, was a god of vengeance. Odin also had other children, as explained by “Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology,” such as Hermod, Heimdal, and Tyr.

Odin was an eclectic god

Odin’s functions in Norse mythology were numerous, but “Odin, Warrior God” points out that his main function was as a god of war. In this capacity, Odin and his Valkyries chose among the slain on the field. Thus, he was also called the Father of the Slain and God of Captives. Odin, however, was more eclectic than just a warrior god.

Norse Mythology for Smart People explains that he was also a god of poetry, having stolen the Mead of Poetry from the giantess Gunnlod. In the myth, through trickery and murder, Odin gained access to the giantess. He turned himself into a handsome man and slept with the giantess for three nights with the promise that he would be allowed three sips of the divine draught that would inspire all he said and wrote. However, instead of taking the three sips, Odin drank the whole thing and escaped to Asgard by transforming into an eagle. He regurgitated the draught back to the gods and drips of the divine mead escaped from his beak to land in Asgard, where it was said they inspired average scholars and poets. Those who were true masters were given the mead directly by Odin himself.

Odin was also a god of outlaws, magic, and knowledge. This last quality, and the quest for it, was the all-consuming characteristic of Odin.

Odin ran Valhalla

Odin’s palace in Asgard was Valhalla. Valhalla had special significance to the Norse since it was populated with warriors who were slain in battle, who were chosen by the Valkyries. These warriors were selected to be a part of Odin’s army which “Odin, Warrior God” explains was called the Einherjar. Others who may have died in battle but were not chosen by the Valkyries went to the goddess Freyja’s Folkvang, also in Asgard. Going to Valhalla was the ultimate goal of any Norse warrior.

Valhalla is described in the Old Norse book of myths, the “Prose Edda.” It is an immense palace with over 600 doors, through which 800 Einherjar could walk abreast. Each day, the warriors feasted on the boar Saehrimnir, which renewed its flesh every day. The goat Heidrun provided a limitless supply of mead from her teats. Thus the Einherjar feasted and fought. Those who died were revived at the end of the day. This life of nonstop battle and partying went on for eternity until the warriors rode with Odin to Ragnarök, the final battle at the end of the world.

Odin gave up his eye for wisdom

Gods in polytheistic traditions are generally not omniscient like monotheistic gods. Odin did not know everything, but he sure wanted to. Much of the god’s character arc is spent on his quest for knowledge of all things — past, present, and future.

One of the most famous myths concerning Odin is how he became one-eyed. “Gods, Heroes, and Kings,” summarizes that Odin journeyed to Jotunheim, the land of giants, where he followed the root of the world tree Yggdrasil to Mimir’s Well. Mimir was a god known for his wisdom, which was imparted by the waters of the well. Odin wanted to drink that water, so he asked Mimir if he may. Mimir said that he could, but that he needed to deposit his eye in the well first. Odin agreed and removed his own eye and drank the water. Of course the god gained much wisdom, but he found that the more he drank, the more he wanted to know. Meanwhile, the eye remained concealed at the base of the well.

This tale is sometimes called “Fjolnir’s Pledge.” Fjolnir means the “concealer,” and it was another name of Odin.

Odin sacrificed himself to gain knowledge

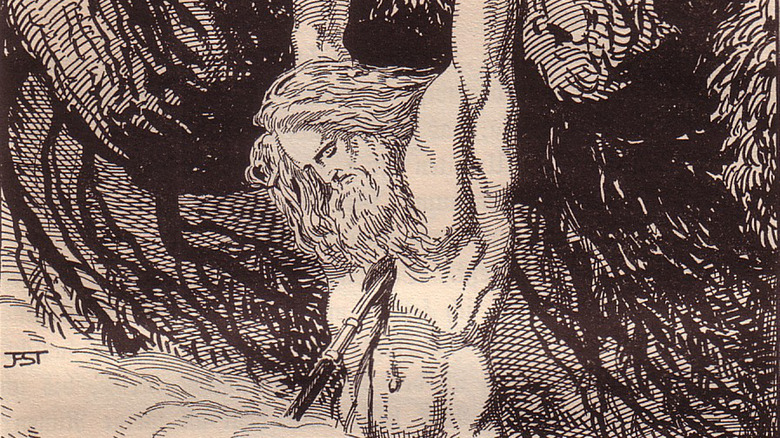

Odin was so consumed to know all that he sacrificed himself to gain even more wisdom. One of the most evocative stories from Norse myth is Odin’s quest to understand the power of the runes. The runes were magical, a symbol of magic and power. Norse Mythology for Smart People, explains how Odin wanted to learn the knowledge of the Norns, who were the personification of fate and masters of the runes. To prove himself, he needed to torment himself.

“Ethics and Medievalism” quotes parts of the “Hávamál,” which is a poem found in the “Poetic Edda” that describes how Odin hung himself from the world tree, Yggdrasil.

I hung, I know,

on the wind-tossed tree

for nine nights in all,

suffered the spear wound,

was offered to Odin,

— myself to myself —

tormented on the tree

which rises from roots

hidden from human kind.

Odin refused all help, and on the ninth night the power of the runes came to him. He became a master of magic. He could heal. He could emasculate his foes. He could even wake the dead. As noted in “Religion of the Gods,” this sacrifice of Odin is sometimes compared to Jesus Christ due to its similarity, and it is sometimes thought that the Christ story inspired the Odin story. However, Odin’s tale is likely a separate cultic practice.

Odin had interesting animal friends

“Odin, Warrior God” explains that ravens were specifically associated with Odin because of their appearance on the battlefield as carrion birds. Odin had two special ravens, Hugin and Munin (sometimes Muguinn), whose names mean thought and memory respectively. Both birds flew throughout the world gathering knowledge and information to return to the allfather. The raven featured prominently in Norse heraldry as a result. If ravens were seen after a sacrifice, it was believed that Odin had accepted the offering. Is written in the “Elder Edda” that Odin said:

Hugin and Munin

Each dawn take their flight

Earth’s fields over.

I fear me for Hugin,

Lest he come not back,

But much more for Munin.

Odin also rode an eight-legged horse named Sleipnir. According to Norse Mythology for Smart People, the name means the “sliding one” and Slepnir could ride as easily in the air as on land. The horse has a rather unsavory origin, being the offspring of the trickster god Loki and a stallion in a plot to deceive a giant. According to “Odin: The Viking Allfather,” the god also possessed two wolves that laid at his feet during feasting: Freki and Geri, whose names both mean the “greedy one.”

Odin had powerful accoutrements

Odin had some nifty accessories. Two of the most famous are his spear, Gungnir, and the ring Draupnir. Both of these came into Odin’s possession through Loki. The story, as related in “Tales of Valhalla,” describes how Loki had abused the goddess Sif and cut off her golden hair. Thor threatened Loki with extreme violence if he did not replace her hair. Loki, therefore, went to the dwarves and not only obtained replacement gold hair for Sif, but other valuable items including Gungnir, which means “swaying,” as well as a ship for the god Freyr. Loki then bet his head that the dwarves could not make three more objects just as valuable. The dwarves accepted. In order to save himself, Loki transformed into a fly to distract the dwarves. While he managed to disturb the creation of Mjolnir, Thor’s hammer, it did not disturb the forging of a golden boar, as well as the ring Draupnir.

Loki later presented these gifts to the gods and give Gungnir and Draupnir to Odin. No special abilities are attributed to Gungnir, although it could be assumed to be a powerful weapon. Draupnir, for its part, was a source of limitless wealth. Every ninth night, the ring would drip eight new rings. As an afterword, the dwarves had won the bet, but Loki noted that the dwarves owned his head, and not his neck so it had to stay on it. The dwarves, instead, sewed his mouth shut.

Odin's helpers were the Valkyries

Odin, as pointed out by “Odin, Warrior God,” was a tactician and strategist who the Vikings prayed to for victory. He was no warrior. In fact, certain tactics, such as the svynfylking or “swine array,” a wedge formation, were attributed to Odin although it is more likely that the formation came from the Romans. Much of the reason why Odin was the warrior god was because it was he and demi-gods called the Valkyries who chose among the slain in battle to bring them to Valhalla in the afterlife.

The number of Valkyries vary throughout the mythology. In the beginning, there were six Valkyries but later on they could appear in groups of up to 27. The Valkyries themselves would make a dramatic appearance to the battlefield, riding through lightning in bloody mail and wielding a spear. These maidens of Odin were also called the Witches of the Shield, Maidens of Victory, and Maidens of the Slain. “The Norse Myths” explains that the Valkyries influenced the course of battle, but they also accompanied Odin on the “wild hunt” through the skies. Some were apparently daughters of the god.

Odin accepted human sacrifices

Sacrifice was very important to the Vikings, both animal and human. “Odin, Warrior God” explains that there were three main sacrificial events on the Norse calendar. One of these, called the Sigrblot, meant “victory sacrifice,” and was dedicated to Odin. It was celebrated in the early spring. The purpose of the event was to gain the favor of the war god to bring victory in battle during the upcoming raiding season. Sacrifice also occurred before and after battle. Indeed, the warriors who the Vikings were about to slay could be seen as a sacrifices to Odin.

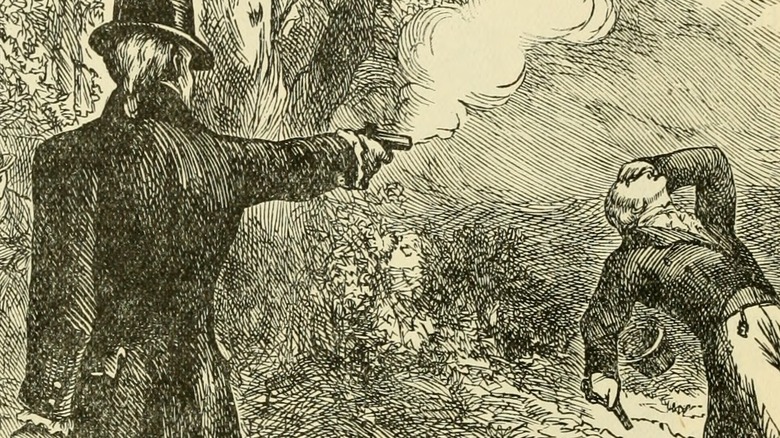

There were also more significant religious events that required sacrifice. “The Untold History of the Vikings” details how every nine years, nine men were sacrificed as part of a religious festival in Uppsala, now Sweden. Every day for nine days one victim, in emulation of Odin’s self-sacrifice, was hung from a tree. Typically, the sacrificial victims were criminals or outlaws, although at times of desperation others might be given over to the god.

Odin often disguised himself

“Myths of the Pagan North: The Gods of the Norsemen,” explains that Odin was well known in Norse mythology for his trickery and his willingness to betray others. This is reflected in the gods’ many disguises. Odin did this to gain knowledge, such as when he went to Mimir’s well or when he disguised himself to steal the Mead of Poetry. Another instance of Odin’s use of disguise is how he needed to use multiple transformations to finally seduce the giantess Rind. One of his most famous disguises, as told by “Odin: Ecstasy, Runes, & Norse Magic” is that of Grimnir, which means “hooded one.” The god disguised himself as a cloaked and hooded old man. Sometimes he wore a hat. Think of how Gandalf from “The Lord of the Rings” looks, but with only one eye. Sometimes Odin was called “the wanderer.”

Because of the ever changing nature of Odin, it was easy for the Norse to begin to associate him with Jesus Christ when polytheism gave ground to Christianity. As pointed out by “Vikings at War,” the Norse assumed Christ was one of the disguises of Odin.

Odin was doomed to die at Ragnarök

In Norse mythology, Ragnarök is the final battle of the gods and the end of the world, which ultimately leads to a renewed world. As the World History Encyclopedia explains, at Ragnarök the forces of the underworld, which included Loki and his children, Hel, the Midgard Serpent, and the wolf Fenrir, lead the forces of darkness against the Aesir and the host of the Einherjar led by Odin.

Odin may have caused Ragnarök. The god learned a prophecy that Loki and his children would cause trouble, so he exiled Hel and Loki, as well as chaining the terrible Fenrir. This no doubt alienated them.

“The Handbook of Norse Mythology” explains that at this final battle, Odin fought the fearsome Fenrir, who had broken from his chains. Fenrir had already swallowed the sun, and his jaws were as wide as the Earth to the heavens. Odin attacked Fenrir with Gungnir, but he was swallowed by the world. According to the “Prose Edda,” Odin is immediately avenged by his son, Vidar, but it is too late. This maw was a symbol of the void, and as Odin entered it, so too did the old world that he had helped create. In this respect, Odin was a fulfilment of the cyclical nature of Norse mythology.

The Billy The Kid Theory That Could Change Everything

The Real Reason The Gnostic Gospels Aren't In The Bible

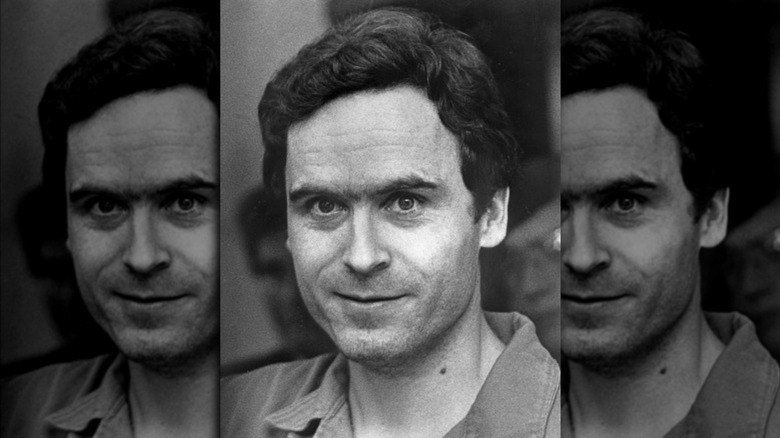

What Was In Ted Bundy's Trunk The Night Of His First Arrest?

Little Known Secrets That Rock Star Obituaries Revealed

Here's What The Bible Really Says About Immigration

Why Joel Osteen's Teachings Have Been Compared To Atheism

The Crimean War Was The First To Feature These Two Things

What Heaven Really Looks Like In The Bible

The Tragedy Of David Berman

America's Oldest Commercial Soft Drink Isn't Coca-Cola