The Surprising Mental Health Benefits Of Listening To Metal Music

Headbanging, mosh pits, devil horns, walls of death, swirling vortices of stomping, rampaging concert-goers who might strap on a stilted suit and tie come Monday. We get it, the assumption is easy to make: angry music, angry people. But by the same token, we doubt that anyone who listens to easy-breezy pop wants to be classified as an “airhead.” Nothing and no one can be so easily stripped down.

Music exists, in part, to express the ineffable, the inscrutable, and the uncapturable by words or other means. It relates the densest complexities and richness of human experience, not its most reduced simplicities. It’s lightning in a bottle, like the two-minute climax of a moving film that leaves people crying. In the same way, the catharsis of music is defined by its transience — it comes and goes, much like glee, or a sunset, or flash-in-the-pan rage.

So what are we to make of metal and its listeners? Is it all about connecting to “primitive” sensations that have driven our species to survive since its earliest days? Is it merely an excuse for some puerile jerks to act like man babies? Anyone who has turned to a favorite song or musician for comfort at a critical juncture in their life should understand the truth. Metal produces a veritable cornucopia of well-researched, well-documented mental health benefits: reduced blood pressure, calmer baseline emotions, better adjustment in middle age, and much more.

Reduced anger, anxiety, stress, sorrow, and more

Out of all available resources, a 2015 article in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience best sums up the mental health benefits of listening to metal: “Extreme music matches and helps to process anger.” In its most basic form, the study showed that metalheads experienced better emotional regulation not just when listening to metal but in general. When listening, feelings of relaxation matched and eventually surpassed those experienced in absolute silence.

The study’s design is easy enough to understand. There was a questionnaire component where participants answered questions about their listening habits and a biometrics component that measured bodily responses such as heart rate when listening to metal tracks by various artists. These biometrics were compared with a Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) inventory, which basically asks people to self-report how they’re feeling at a given moment. And to be clear, when we say that participants listened to “metal,” we’re not just talking ’80s thrash. We’ve got power metal, metalcore, death metal, black metal, nu-metal, prog metal, and lots more. There were 46 artists total, including Meshuggah, Trivium, Amon Amarth, Judas Priest, Danzig, Tesseract, and even more poppy-dancy industrial stuff like “Dragula” by Rob Zombie (yes, it’s still metal — purists be silent).

Participants didn’t just process anger better, but also depression, sorrow, anxiety, stress, and more. In the end, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience wrote, “Extreme music fans reported using their music to enhance their happiness, to immerse themselves in feelings of love, and agreed that their music enhanced their well-being.”

Old stereotypes flipped on their heads

Truth be told, none of this information will be the least bit surprising to any metalhead. It’s not uncommon for non-fans, when discovering that someone likes metal, to say something like, “You listen to metal? But you’re so chill.” A good reply would be, “Yeah, that’s why I’m so chill. Let’s go listen to Cattle Decapitation.”

But where does the misconception of the opposite come from? Where does the belief arise, amongst non-listeners, that metal is a breeding ground for violence, hatred, anger, etc.? Is it simply the sound of high-tempo, double kick-drummed, sometimes growled music? Is it decades-old biases stemming from metal’s roots in the countercultural dissatisfaction of punk and “extreme” music in the late 1960s? Is it lyrics such as Cannibal Corpse’s “Sawing the neck I am engulfed in fantasy / Chew the esophagus, cannibal delicacy”? Okay, fine, we’ll grant you that last one. (Side note: Don’t make Cannibal Corpse your first foray into metal.)

Along those lines, Bloodbath lead singer Nick Holmes said on the BBC of his band’s song “Eaten,” “I would be frankly astounded if anyone listened to that song and then felt a desire to be eaten by a cannibal.” This piece of clever rhetoric reveals the truth about metal: It’s a self-aware gateway to admitting, embracing, and facing one’s demons. As Holmes says, metal listeners are “the equivalent of people who are obsessed with horror movies or even battle re-enactments.”

Abutting the poison of neo-Nazism

Plenty of other studies and articles have chimed in to support these kinds of claims. The Guardian reported on the link between metal and classical music that is taken for granted amongst metalheads. Whether it’s Metallica or Mozart, “Metal fans, like classical listeners, tend to be creative, gentle people, at ease with themselves,” the publication wrote. “We think the answer is that both types of music, classical and heavy metal, have something of the spiritual about them — they’re very dramatic — a lot happens,” researcher Adrian North said.

On Loudwire, Professor Bill Thompson said of death metal, specifically, “[Death metal] fans are nice people.” He cites a psychological phenomenon called “binocular rivalry” to explain metal’s ill-labeled reputation: people tend to remember violent images more than non-violent ones. And then there’s Finland, the World Happiness Index’s happiest country in the world four years running (per the BBC). The frosty, introverted nation has more metal bands per person than any in the world, at a whopping 53.5 bands per 100,000 people, per This is Finland.

So as The New Yorker asks, how do we account for metal’s on-again-off-again connection to white rage and neo-Nazism? What of poisonous events like Woodstock 99, where there were literal gang rapes in mosh pits during nu metal vanguard Limp Bizkit’s set? Simply put, metal was always anti-establishment, anti-usury, and anti-fascist. Those who believe themselves oppressed — justly or not — can grab ahold of the language of metal and wield it as their own.

Metal and Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT)

The mental health aspects of metal music really come into focus when viewed in terms of Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT), a therapeutic model that rings very loudly of common sense. As Dr. Les Greenberg on The Counseling Channel says, it focuses on the difference between “primary” and “secondary” emotions. A primary emotion is the first thing you feel when something happens, but the secondary emotion — usually slower to notice — is the underlying, unmasked emotion. In other words, if Danny gets angry when he discovers his partner’s infidelity? That’s his primary emotion. What’s he really feeling? He’s incredibly sad. That’s the secondary emotion, without any filter or mask. EFT teaches people to focus on secondary emotions to suss out how they really feel.

EFT dovetails nicely with what’s known as “projection” in psychotherapy, which is the kind of thing that happens if secondary emotions go unaddressed (per Healthline). For example, someone thinks, “I’m unhappy at work, so I’m going to get home and take it out on the dog. It’s the dog’s fault for pissing me off.” Along these lines, Dr. Greenberg speaks further of a “sexual stereotype” that we all know too well: “Men who have difficulty with vulnerable feelings like fear and shame often express anger.”

It’s not too difficult, then, to see how metal music provides a method to “process” primary emotions of anger, as the original 2015 article in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience states. If done mindfully, listening to metal can allow true secondary emotions to rise.

A musical space for true emotions to rise

We can test the connection between metal and Emotion-Focused Therapy by looking at song lyrics. Bear in mind that it’s impossible to cover all cases and variety of content — we’ve already seen that songs can talk about intentionally ridiculous things like cannibals — but we can provide an overall picture.

According to Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, metal’s lyrics typically aren’t angry but focus on “themes of anxiety, depression, social isolation, and loneliness.” In the case of bands like French prog outfit Gojira, this extends to sorrow about issues like the destruction of the Amazon rainforest. Amenra, a Belgium-based extreme group, paints highly introspective, pathos-filled poetic verses in songs like “A Solitary Reign,” saying, “I wanted you to stay / Yet you died away / Your touch divides / I see distance in / In your eyes.” Yet, as Frontiers in Neuroscience says, metal music itself is “characterized by chaotic, loud, heavy, and powerful sounds.” This certainly matches the primary emotion (anger) vs. secondary emotion (sorrow) dichotomy that EFT discusses and exemplifies the better emotional regulation that metal listeners exhibit. Plainly put, metal lets people know that others feel the same as them. This is key to mental health.

So what of the aforementioned neo-Nazis and angry white men of nu-metal? It might come down to the content itself, the culture those individuals are embedded in, or a host of other reasons. Outliers, too, help define the mean.

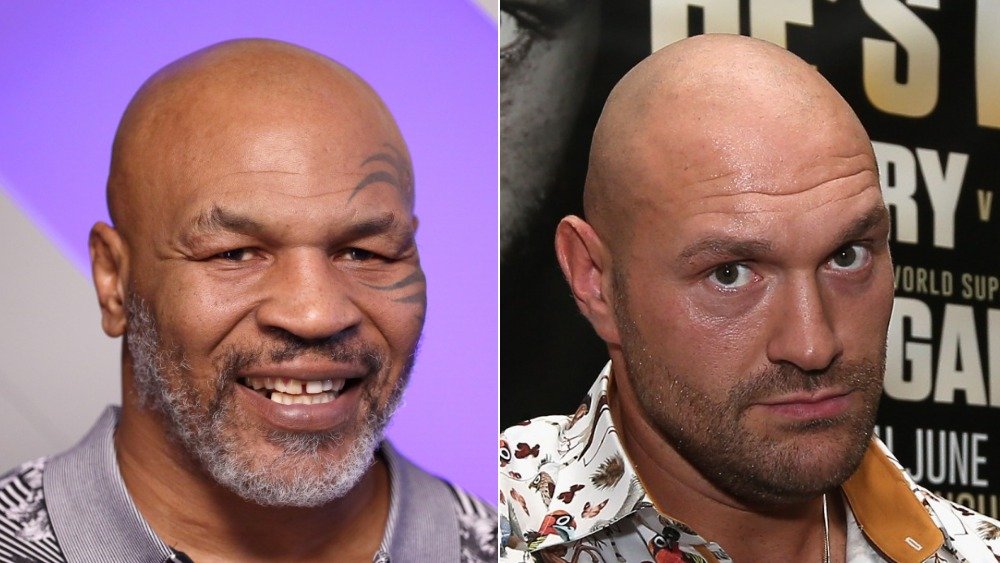

How Music Experts Taught AI To Compose Beethoven

Did Alexander The Great Really Play A Role In His Father's Murder?

The Truth About The Man Who Discovered Troy

This Is What Really Happens To Your Body In The Electric Chair

The Stunning Amount The United States Spent On The Afghanistan War

The Shakespeare Conspiracy That Would Change Everything

The Scary Thing That Happened To Billy Idol's Eyes

This Was Huey Lewis' Biggest Regret Of His Career

Why Robert E. Lee Couldn't Scare Off Ulysses S. Grant

Here's What Happens When You Get Jerusalem Syndrome