When A Town In France Was Poisoned By Bread

What could cause hundreds of people in a village in the South of France to suffer from an illness that caused violent hallucinations? Some claimed that their children had been turned into sausages, while others saw imaginary fires everywhere. One man even jumped out of a window and kept running briefly after breaking both of his legs, writes Mental Floss.

To this day, several theories have been put forth but no one really knows exactly what happened in Pont-Saint-Esprit on August 15, 1951. Historically, there have been several instances of ergotism — poisoning due to a fungal disease present in contaminated grain products — causing similar hallucinations, especially in the Middle Ages, per Smithsonian Magazine. But despite the fact that the active component in ergot, lysergic acid, is used to make LSD, it’s debated whether or not ergotism is responsible for the 1951 mass poisoning. Some have even gone so far as to suggest an international conspiracy was responsible. But even though no one knows exactly what caused it, the bread is definitely not innocent. But what exactly happened during the summer of 1951 that could have led to such a mass poisoning?

The government monopoly on flour

After World War II, the French government kept some governmental systems of the Vichy government, including their control over the grain supply chain. According to Haaretz, while control of the wheat crop was always an essential part of the French state’s foundation, the process of transporting flour so it was accessible to everyone started being standardized and supervised by the government during the Vichy regime.

Unfortunately, under this system, bakers couldn’t choose the millers that they wanted to work with, even if they got flour of inferior quality. And sometimes when flour was sent to “distant regions,” it was often mixed with non-flour substances, which not only affects its quality but can be “life-threatening.”

In “The Day of St. Anthony’s Fire,” a book about the incident, John G. Fuller writes that bakers also couldn’t refuse the deliveries of flour, and the only thing they could do if they were unhappy with the flour was to notify the Union Meunière, the “state-supervised private monopoly” that distributed flours to bakers across France. If a baker wanted to reject the flour for poor quality, they’d essentially have to close their shop for a few days while they waited for the Union chemists to check the flour themselves, with no guarantee that they’d agree with the baker.

Previous outbreaks of food poisoning

The mass poisoning in Pont-Saint-Esprit unfortunately wasn’t the first time that bakers in the area were suspicious about their bread. And bakers in the region had been complaining about the quality of flour that they’d been receiving for some time. According to “The Day of St. Anthony’s Fire,” most of the bakers got flour from the Maillet mill, and almost every single baker insisted the flour led to a virtually unusable dough.

Bread wasn’t the only thing that was causing food poisoning at the time. Haaretz writes that in the same year as the mass poisoning in Pont-Saint-Esprit, more than 100 people died from eating tainted horse meat in the north, and children in the city of Metz were made ill by contaminated milk powder. According to H-France Review, French newspapers at the time told their readers that it was difficult to tell whether the food they purchased was the “product of fraud or negligence.”

Mass poisoning

The mass poisoning is believed to have begun on August 16, 1951, in Pont-Saint-Esprit, France. One of the first patients arrived at Dr. Hadar Gabbai’s clinic around 10 in the morning, mumbling incoherently. Soon another villager came in, and according to Haaretz, it took three people to convince the man that “snakes were not slithering across his body.” By the end of the day, doctors counted at least 75 hallucinating villagers and many had to be restrained to their beds with rope in order to keep them from hurting themselves or others.

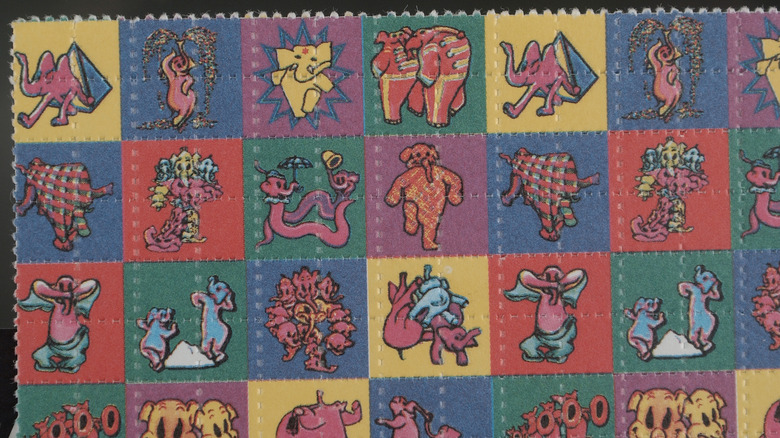

Smithsonian Magazine writes that over the following week, more than 200 more villagers were affected. While some people experienced symptoms that resembled food poisoning and experienced a few days of nausea and insomnia, others faced much more severe symptoms. These ranged from seeing snakes and tigers to experiencing “convulsions and swollen limbs that felt as if they were burning, some turning gangrenous.” Some people even experienced early menstruation as a result of the poisoning. To be fair, not everyone had a bad time, and Mental Floss writes how some people heard “heavenly choruses” and “saw brilliant colors.”

According to “Ergot Poisoning at Pont St. Esprit” by Dr. Gabbai, Dr. Lisbonne, and Dr. Pourquier, four people died as a result of the mass poisoning. Humans weren’t the only ones affected by the mass poisoning. In “The Day of St. Anthony’s Fire,” Fuller writes about several cats and dogs that also died after eating the reportedly poisoned bread.

Doctors investigate

In “Poisons,” Peter Macinnis writes how dozens of people had to be restrained with straitjackets, and at one point, an 11-year-old boy even tried to strangle his mother. Doctors were all absolutely dumbfounded and in their investigation, they determined that the cause of the mass poisoning may be attributed to ergot fungi.

According to Mental Floss, the belief was that since the summer of 1951 had been “especially wet,” this led to ergot fungi growing all over the rye fields. As a result, the Roch Briand bakery received tainted grains lead to the baker using “fungus-contaminated flour.”

But the president of Union Meunière, M. Jacob, claimed that ergot couldn’t possibly be the cause and that it’s constantly being eaten in bread anyway. And while traces of ergot were found in some tests, according to “The Day of St. Anthony’s Fire,” many question whether there would’ve been sufficient quantities of ergot to cause such a mass poisoning, since even those who ate small amounts were affected. Any high concentrations “would have made the bread literally inedible.”

In “LSD,” authors M. Foster Olive and D. J. Triggle, rejected the theory of ergotism in favor of mercury poisoning, since mercury was often used to kill fungi and mercury poisoning can lead to symptoms similar to ergotism.

The police get involved

In addition to the investigations by medical experts, law enforcement got involved as well, but it seems as though each different inquiry led to a different theory. One investigation determined that the flour became contaminated because it was transported “unhygienically in polluted train cars,” writes Haaretz. Another believed that the contamination came from factories whose fuel leaks contaminated water supplies.

Another theory blamed the materials used to bleach bread, but the French government decided not to investigate this theory further, a decision that historian Steven L. Kaplan calls “outrageous.”

In the end, Maurice Maillet and Guy Bruère ended up being arrested and formally charged on September 1, 1951, for supplying dangerous food products, falsifying records, and involuntary homicide. Fuller writes in “The Day of St. Anthony’s Fire.”

While rumors spread that the Union Meunière was trying to do everything it could to blame the bakers and the millers, Maillet’s flour supply was tested. However, it showed the ergot levels to be negligible. And since “no causal chain could be established” to connect Maillet to the Pont-Saint-Esprit tragedy, it appears as though the charges against both men ended up being dropped. The New York Times writes that in 1978, “the [whole] affair was finally dropped.”

Was it the CIA?

At the end of the day, no one knows exactly what caused the mass poisoning in Pont-Saint-Esprit. And in 2009, another theory was put forth that placed the blame solely on the CIA.

According to Mental Floss, in the book “A Terrible Mistake,” author Hank P. Albarelli, Jr. suggests that the CIA was connected to the poisoning in Pont-Saint-Esprit. Albarelli claims that he discovered a document that suggests that the CIA was involved in the mass poisoning along with Frank Olson, who was a CIA scientist researching LSD during that time period who also ended up also being unknowingly drugged by the CIA, per The Guardian.

France 24 also writes that the CIA reportedly tried to expose the village to LSD through “an air blitz” of crushed LSD. But after this didn’t work, it was then that they tried to move on to local food contamination. Considering the CIA’s history with LSD, the theory isn’t actually so far-fetched, but there’s relatively little evidence supporting this theory.

But some, like historian Kaplan, are unconvinced by the CIA conspiracy theory, especially since LSD doesn’t cause the types of symptoms that occurred during the mass poisoning and typically sets in much faster than the 36 hours it took for a majority of the people in the village to show symptoms. But Kaplan doesn’t believe that ergotism is the cause either, especially since the last-known case in France had occurred in the 18th century.

This Is What The Bible Says About Pork

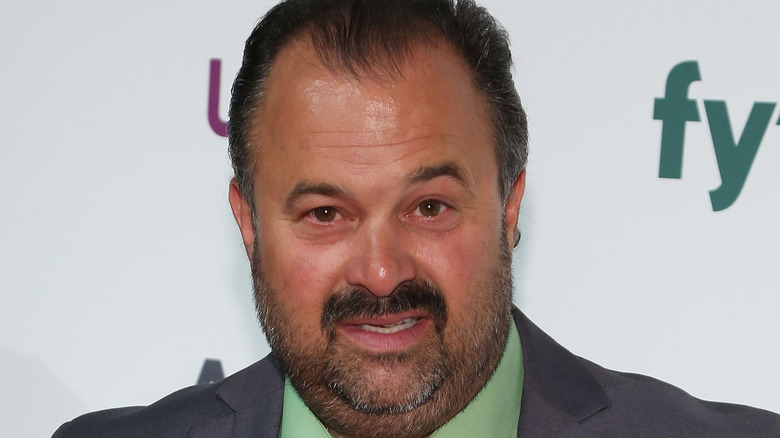

The Time Someone Sued American Pickers' Frank Fritz

This Was The Problem With Charles VI Of France's Reign

Herb Baumeister: The Truth About The Suspected Serial Killer

What Cary Grant Did After Retiring From Acting

The Queen Didn't Go To School. Here's Why

How Drugs Ruined Sly Stone's Life

'Mathematicians, Geeks' Celebrate A Rare Palindrome Day

The Real Reason Airplanes Are Almost Always Painted White

People Who Vanished While On Vacation