Judas And The Black Messiah: The True Story Explained

There are some stories better left untold. This is not one of them.

The tumultuous American days of the Vietnam War, civil rights movement, and fear of communism serve as a backdrop to Judas and the Black Messiah, a modern tale of Caesar and Brutus. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X are household names, but how many have heard the name Fred Hampton or William O’Neal? Luckily, Judas and the Black Messiah is changing that.

Historical fiction has the potential to tease a history lesson, but we must remember, it’s still fiction. Nevertheless, some filmmakers do the history part justice better than others. According to Screen Rant, Judas director Shaka King relies heavily on the facts, molded together by a haunting, melodramatic tone.

Below is a breakdown of the truth behind the story, as well as when the filmmakers took liberties. Hopefully you’ve seen the movie by now because…

*Spoilers below!*

Who was William O'Neal?

William O’Neal was a petty thief-turned-FBI informant at the time the film takes place. He was responsible for providing the Chicago police with invaluable intel about young activist Fred Hampton and the Chicago chapter of the Black Panthers, as well as the floor plan to Hampton’s residence. He became a trusted member of the chapter and worked as head of their security detail.

It’s pretty near impossible to find footage of O’Neal, with one exception. At the end of Judas and the Black Messiah, the documentary Eyes on the Prize: America at the Racial Crossroads 1965-1985 is mentioned. In the documentary, O’Neal gives his only known on-camera interview, in which he is asked about his time with the FBI. “My recruitment by the FBI was very efficient,” O’Neal says in the documentary. “Very simple really, I stole a car and went joyriding over the state limit. They had a potential case against me, and I was looking for an opportunity to work it off.”

O’Neal was notoriously hated for his part in Hampton’s demise, according to The African Exponent. After his cover was blown, he had to enter the federal witness protection program. He took the name William Hart and moved to California, though he would return to Chicago before his death. O’Neal committed suicide on Martin Luther King Day in 1990, shortly after his interview aired.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Who was Fred Hampton?

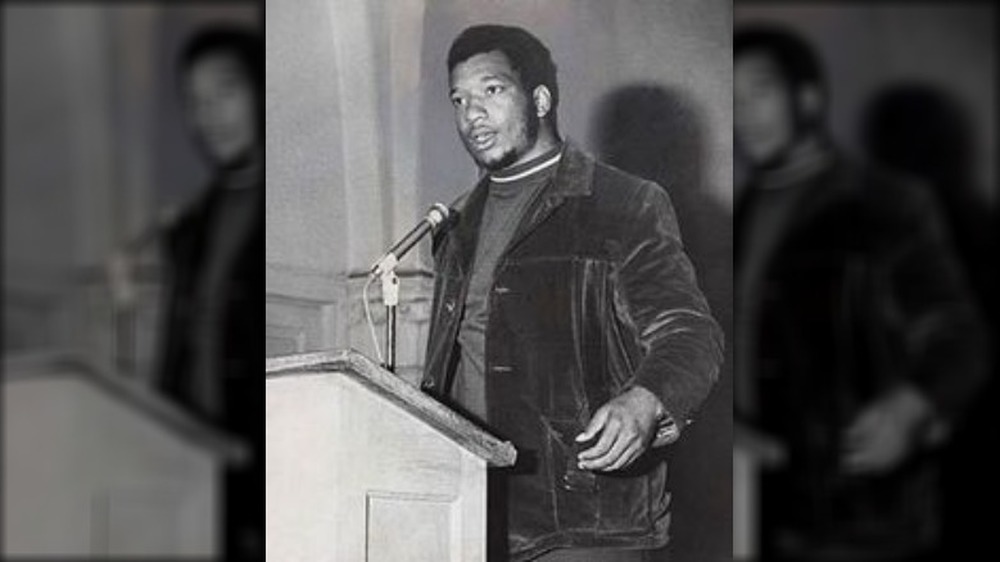

Fred Hampton was a charismatic, driven young revolutionary who became the chairman of the Black Panther Party’s Chicago chapter. He was only 20 years old when he was appointed. According to the Chicago Sun-Times, he began his activism as a student at Proviso East High School, where he led a boycott to allow Black girls to compete for homecoming queen.

Hampton was a fearless visionary and curated powerful coalitions to push back against police brutality in his community. He also strived to provide impoverished Black Chicagoans, particularly children, with food, shelter, and resources.

Hampton convinced Chicago’s most powerful street gangs to stop fighting one another and even to work together. In a 1969 press conference, he notified the public of the nonaggression pact between the gangs, as well as the creation of what would become known as the Rainbow Coalition. The Coalition provided free breakfasts and offered pro bono legal consultations to the community.

The mass media, with the help of the FBI and local police, demonized the Panthers, and Fred was seen as a significant threat to the federal government. As portrayed in the film, and what is now known to be true, is that the FBI directly ordered the hit on Hampton. The legacy he left behind is still alive and well on the streets of Chicago. With the film’s release, many more will learn about this remarkable man who died much too young.

Civil rights and the fear of communism

Take the cumulative effect of American troops fighting “communism” in Vietnam, the fear of Russian influence and the House Un-American Activities Committee, Jim Crow laws, and overt institutionalized racial discrimination, and you have the perfect backdrop for a film like Judas and the Black Messiah.

These tensions were extremely prevalent in Chicago in 1969, when the film takes place, yet are oddly familiar in our world today. Fred Hampton’s “message of grassroots liberation feels bold and current, as does his mistrust of the police and the state,” writes David Sims in The Atlantic. As an NPR report points out, “You could call these movies timely, except that the issues they confront, from the exploitation of Black American culture to white supremacy in law enforcement, have never not been timely.”

Much like in the film, the Panthers endured repeated harassment from the local police at the behest of federal law enforcement. Even before Hampton became involved with the activist group, he faced multiple arrests for things like traffic violations. But why were the Panthers seen as such a threat?

The idea that communism and/or socialism could make its way into American society was the FBI’s public reasoning behind targeting the group. It’s unlikely, however, that a white activist group of the same ilk would have garnered such attention.

The Black Panther Party's Chicago chapter

In 1969, the head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, announced his belief that the Black Panther Party was the “greatest threat to the internal security of the country,” in his annual fiscal report, according to the UPI archives.

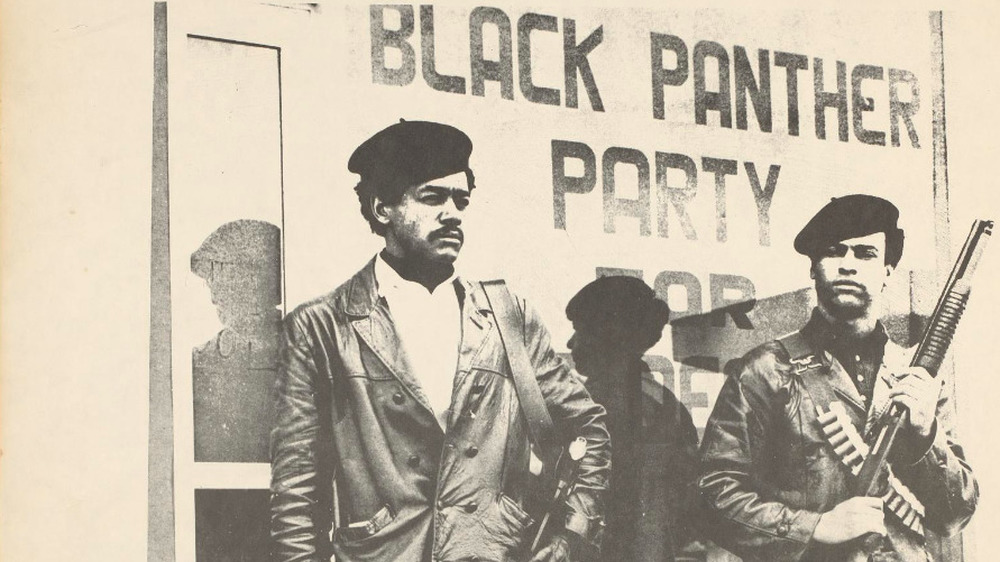

The Black Panther Party was initially founded in Oakland, California, in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale (pictured). Their aim was simply to promote self-defense among Black communities, but controversial publicity for the organization began early on when the BPP demonstrated outside of the California state capitol armed with weapons. Word caught on quickly, and 13 official chapters were formed across the U.S.

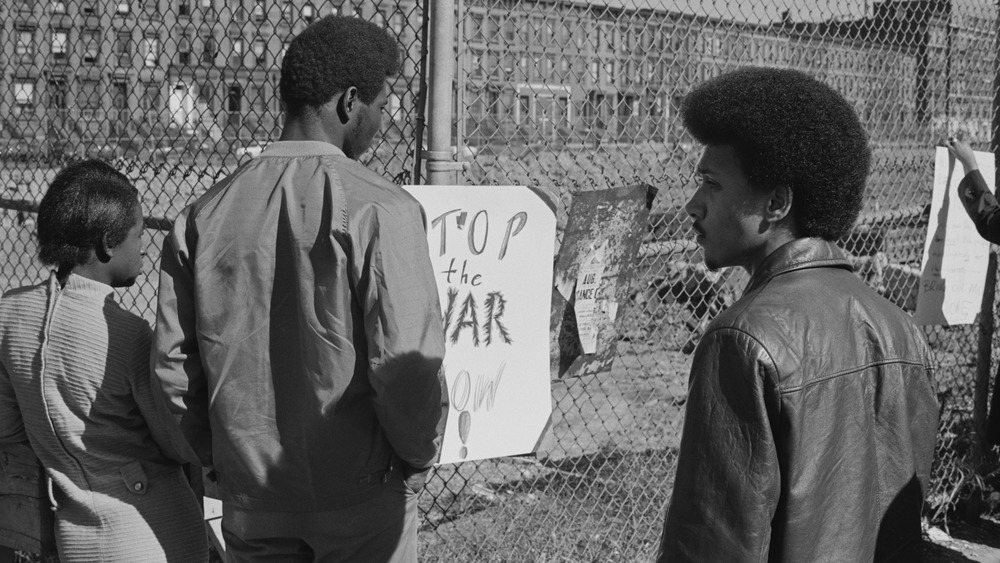

Fred Hampton became the leader of the Chicago chapter in 1968 after now-U.S. representative and then-BPP member Bobby Rush recruited him after hearing him speak. Chicago’s branch had a 10 Point Plan, which included achieving decent housing, employment, food for Black communities, and an end to police brutality in their neighborhoods. The BPP was also very outspoken about their disdain for the Vietnam War.

The Rainbow Coalition

Fred Hampton miraculously brought three activist groups together in Chicago: the white, Southern Young Patriots, a local Puerto Rican group called the Young Lords, and his Black Panther Party chapter. Together, they were officially known as the Rainbow Coalition of Revolutionary Solidarity. Like in the film, Hampton convinced the groups to work together for a common cause: to keep the Chicago police honest and to keep them from further degrading their communities.

“We got to face some facts,” Hampton said in 1969, according to an article in the Journal of African American Studies. “That the masses are poor, that the masses belong to what you call the lower class, and when I talk about the masses, I’m talking about the white masses, I’m talking about the black masses, and the brown masses, and the yellow masses, too… We’re gonna fight racism with solidarity… capitalism with socialism.”

Hampton, a self-proclaimed revolutionary, saw a common cause that many could not. The Coalition served as a model for future powerful diverse organizations, such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC).

Was Fred Hampton really arrested for ice cream?

Yes. Fred Hampton was cautious and strategic, so the FBI had to get creative in order to justify an arrest to send a message. The real William O’Neal even admitted in his sole documentary interview that it was very difficult as an informant to find things to pin on Fred.

The best the police could come up with was a bogus charge for robbing an ice cream truck driver for $71 worth of cold treats inside. Hampton plead not guilty and protested that he wasn’t even near the scene of the crime when the local police claim it happened. Nevertheless, he went to jail for the alleged crime. “I may be a pretty big mother, but I can’t eat no 710 ice-cream bars,” Hampton said in an out-of-court statement, as reported by The Nation in 1969.

The judge locked him up on the basis that Hampton and the Panthers openly advocated for “armed revolution,” which, needless to say, has nothing to do with ice cream. To celebrate his eventual release from jail, Fred made his famous, captivating “I am a revolutionary” speech at a local church, as portrayed in the film.

The Crowns

The Crowns are a black Chicago gang in Judas, but it turns out they were fictional. The gang was, however, meant to represent an array of real gangs in Chicago at the time, according to Republic World.

Many activist groups crowded the Chicago streets in the late 1960s and would at times clash over simple methods and approaches of how to achieve the change they sought. Much like the distinctions between the peaceful protest leader Martin Luther King Jr. and the more militantly inclined Malcolm X, there was consternation among the Black community on whether they should use violence as a potential self-defense tactic where needed.

The Crowns represented one of the gangs that followed King’s teachings, and the BPP were more inspired by Malcolm X. They’re used as a sort of foil in the film as an intimidating rival to the Chicago BPP. We are first introduced to them in a bar scene where Fred and a few of his fellow Panthers approach the leader of the Crowns to attempt to broker peace and possible collaboration.

Eventually, Fred did succeed in a similar effort with local Chicago outfits. In a tense scene of the film, Fred and the BPP visit the Crowns’ headquarters and are met with suspicion, but Fred’s charm ultimately wins the day.

What else is fiction?

There are a few details in the film that are simply used for dramatic effect, much like all stories based on reality.

In Judas and the Black Messiah, William O’Neal becomes Fred Hampton’s driver shortly after making initial contact with the BPP as an undercover agent. In real life, O’Neal didn’t drive Hampton around Chicago, but it sure makes for a convenient plot device. O’Neal did, however, become the head of Hampton’s security detail, as well as one of his bodyguards, which isn’t far off. According to The Nation, the real O’Neal did use provocative and violent rhetoric, like suggesting the BPP chapter build an electric chair that they’d use on informants, which is ironic to say the least.

The ages of the two main characters were also fudged for casting. Daniel Kaluuya, who arguably gives the best on-screen performance of his career thus far as Fred Hampton, is currently 32 years old, which is more than a decade older than the real Hampton at the time the story takes place. Similarly, LaKeith Stanfield, who is 29, plays 20-year-old William O’Neal.

Who was Deborah Johnson?

Among Fred Hampton’s loyal fellow activists in the film, and in real life, was his girlfriend, poet Deborah Johnson. She continued to be an active member of Chicago’s BPP after his death and later changed her name to Akua Njeri. Her story is a breath of fresh air, as it not only further humanizes Hampton’s character, but it depicts a woman’s perspective amid the tumultuous backdrop.

“[A] lot of times when we think about these freedom fighters and revolutionaries, we don’t think about them having families … and plans for the future,” director Shaka King stated, per Smithsonian Magazine. “It was really important to focus on that on the Fred side of things.”

Unlike most of the people depicted in Judas and the Black Messiah, Njeri is still alive. Njeri gave actress Dominique Fishback free rein to portray her in the film how she deemed fit, albeit with two pieces of advice: “One, that she did not cry when they assassinated Chairman Fred,” Fishback told the Los Angeles Times. “And she talked about how the Panthers were a very disciplined people and they didn’t speak out of turn, so there were just certain things that she wouldn’t have ever said to Chairman Fred.”

In the film, and in real life, Njeri became pregnant just short of nine months before Fred’s assassination. She gave birth to their son, Fred Hampton Jr., 25 days after the infamous FBI raid that left Hampton and other fellow BPP members dead and more of them injured.

Who was FBI agent Roy Mitchell?

The FBI was working in conjunction with the Chicago police to take down the Black Panther Party. Naturally, as the BPP chapter leader, Fred Hampton became the most desirable target.

Agent Roy Mitchell had up to nine FBI informants within the BPP alongside William O’Neal. O’Neal was recruited directly by Mitchell, as portrayed in the film, after a discussion at Cook County Jail, where O’Neal had been arrested for stealing a car and driving across state lines. Mitchell was known to have a charisma that allowed him to get information quite easily from people. U.S. District Judge Kocoras spoke to the Chicago Tribune about him, saying, “He had an uncanny ability to get close to people and get them to talk.”

Mitchell had a 25-year career with the FBI and participated in some other high-profile Chicago cases, but the Hampton assassination is by far what he remains most remembered for.

J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI's involvement

There is hard evidence that the FBI was following Fred Hampton and that they ultimately bore responsibility for his assassination with cooperation from the Chicago police. J. Edgar Hoover honed in on Fred Hampton because he sensed his star power and ability to manifest change.

Hampton’s story, and the FBI’s guilt, is only coming to the nation’s public attention now, thanks to the film. While some may find it shocking that the Bureau would so brazenly carry out such an attack on a U.S. citizen, others are hardly surprised, given Hoover’s particularly menacing reputation regarding the lives and demise of many public figures, including Martin Luther King Jr.

Hoover claimed, according to UPI’s archives, that “organized terror and violence” disrupted the operations of over 225 institutions of higher learning from 1968 to 1969. Hoover had no boundaries and used everything from surveillance to infiltration to “protect” Americans from “violence-prone black extremists.” Ironically, some Americans, particularly the Black community, needed protection from Hoover.

How was Fred Hampton really killed?

The raid portrayed in the film can be somewhat proven by postmortem investigative reports that countered the FBI’s official report at the time. Fred Hampton was killed on the morning of December 4, 1969, in his sleep during a violent raid, and he had been given a sleeping concoction prior to his death, as seen in Judas and the Black Messiah.

Akua Njeri (a.k.a. Deborah Johnson) recalled the event quite vividly. She was miraculously unharmed amid the gunfire. After the police forced her and other survivors out of the bedroom, they moved toward Hampton’s lifeless body. According to ABC News, she heard the police talking about how someone (presumably Hampton) was still alive. She then heard more gunshots and another officer say, “He’s good and dead now.”

The FBI’s illegal counterintelligence program, known as COINTELPRO, specialized in targeting communist-leaning organizations such as the American Indian Movement, the Socialist Workers’ Party, and powerful individual influencers. Hampton’s murder was part of the operation. Though the FBI had Hampton killed, O’Neal was ultimately held responsible for Hampton’s assassination within his community. Et tu, Brute?

Fred Hampton may not be with us today as he should be, but his legacy has been given a new flame. As Chairman Fred says in one of his most famous addresses, “You can jail a revolutionary, but you can’t jail the revolution.”

Is Mindhunter Based On True Events?

The Truth About Robin Williams And Pam Dawber's Relationship

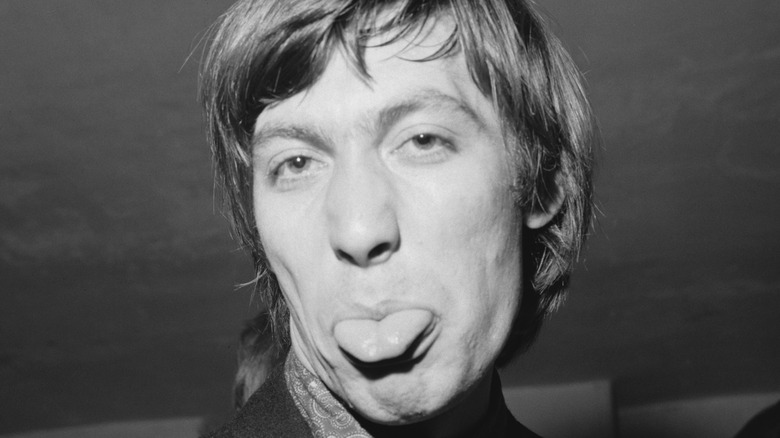

This Was Charlie Watts' Profession Prior To Joining The Rolling Stones

The Reason Slipknot Kept A Dead Crow In A Jar

Hidden Details You Missed In Iron Maiden's The Writing On The Wall Video

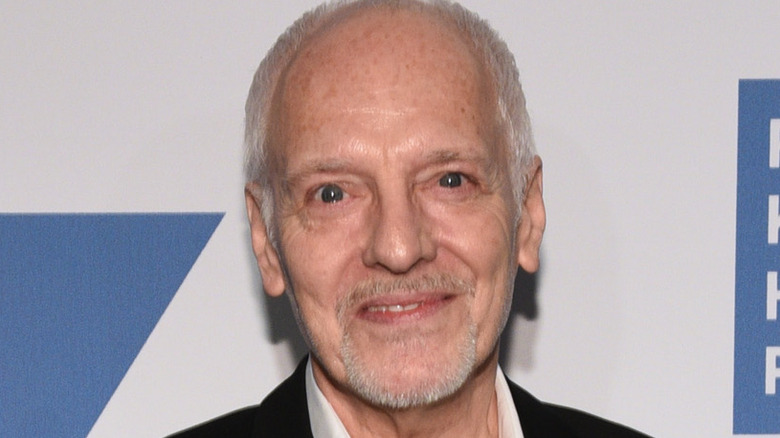

The Untold Truth Of Peter Frampton

What Really Happened To Zeppo Marx After He Left The Marx Brothers

5 Things You Don't Know About The Kid LAROI

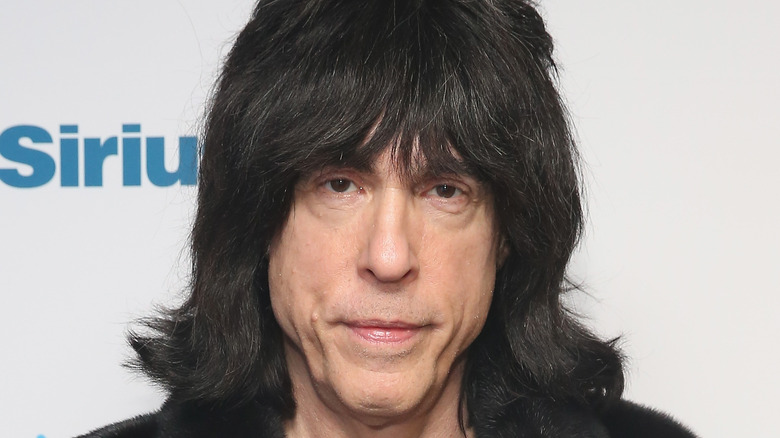

Why Marky Ramone Got Kicked Out Of The Ramones

These Were The Biggest Flops In Broadway History