The 7 Best And 7 Worst Laurel And Hardy Movies

In 1976, the cult writer Kurt Vonnegut published his eighth novel, “Slapstick, or Lonesome No More!” It reads: “Dedicated to the memory of Arthur Stanley Jefferson and Norvell Hardy, two angels of my time.” Though the names are unfamiliar, the accompanying caricatures — in their famous bowler hats and expressing their unmistakable smiles — give away who they are: Vonnegut’s angels are Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, remembered today as the greatest comedy partnership Hollywood has ever known.

It is telling of Vonnegut’s pessimism that he also feels the need to tell us all the way back in 1976 that Laurel and Hardy are figures from “long ago,” artifacts he assumed would soon be forgotten in the ruthless future he envisioned. Yet today, twice as many years away from the heyday of Laurel and Hardy as Vonnegut was when he wrote his book, “the Boys” are still remembered fondly. As the hit 2018 biopic “Stan & Ollie” attests, the appeal of the famous duo is as great as ever, as new audiences continue to rediscover their timeless comedies.

But even the greats can have an off day. Here is a rundown of the finest Laurel and Hardy flicks that you need to see … and those that you can guiltlessly miss.

Hit: Way Out West (1937)

Greatness is subjective, but when it comes to Laurel and Hardy movies, “Way Out West” is certain to feature on any fan’s must-watch list. Opening with an instantly pleasing shot of Stan Laurel leading a donkey down a dusty road, with Oliver Hardy’s bulk being pulled behind on a makeshift sled, with Hardy smiling and dozing, “Way Out West” is a bona fide Western parody (per Empire) that contains a number of the most famous set pieces in the Boys’ entire filmography.

Stan and Ollie are heading to the Wild West on an important mission: to give the deed to a late man’s gold mine to his daughter, who is lodging with “guardians” in the town of Brushwood Gulch. Once there, they enter a saloon, performing as they arrive an irresistibly silly dance routine to “At the Ball, That’s All,” with a Western-looking group of men sat on the porch outside. Another classic set piece arrives a few minutes later, when Stan and Ollie join in with a rendition of “On the Trail Of The Lonesome Pine,” a song with which they will forever be associated thanks to a brilliantly funny vocal gag performed by Stan Laurel (with the aid of sound trickery).

The whole movie is chock full of great gags, particularly from Laurel — his being able to inexplicably use his thumb as a lighter or attracting a pack of wild dogs after fixing a hole in his shoe with a tough steak — but nothing compares to his performance when the ruthless wife of the saloon owner tickles him ferociously in an attempt to get him to surrender the deed to her. Stan’s extended, high-pitched laughter is so infectious that you can even see the actress performing with him struggling to control her smirk.

Miss: The Big Noise (1943)

“Way Out West” was one of a slew of Laurel and Hardy movies from the 1930s that are counted among their finest. By the 1940s, however, things had changed for the comedy team, at least in terms of the critical response to their work.

“The Big Noise” has been roundly criticized for what fans see as the cynical rehashing of old jokes culled from Laurel and Hardy’s earlier movies. The movie lacks the exquisite timing of the duo’s performances of the previous decade, and often appears as though they are ripping off their own work, as if Laurel and Hardy had finally run out of ideas.

As James Travers of French Films has noted however, the real problem with “The Big Noise” is that, for a Laurel and Hardy movie, there isn’t enough Laurel and Hardy in it, with far too much screen time given over to secondary plots and characters whose cloying wackiness doesn’t tick the box in terms of offering the kind of belly laughs that Stan and Ollie could deliver in their finest moments.

Hit: The Music Box (1932)

The most famous of all Laurel and Hardy’s short films, the premise of “The Music Box” is as simple as it is ingenious: two foolish delivery men — played by Stan and Ollie, of course — attempt to take a piano up an enormous stoop to a house on top of a hill. On the way, they encounter numerous obstacles — a rude resident who refuses to let them pass, a police officer who wants to arrest them after an altercation with a woman pushing a pram on yet another fruitless attempt to haul the delivery up the narrow steps — but none are quite as daunting as the pair’s own massive stupidity and utter lack of spatial awareness. The brilliance of the duo’s performance is highlighted in a late gag involving the two characters accidentally swapping hats, which winds up being far funnier than it perhaps deserves to be.

Released at the dawn of their long association with Hal Roach Studios, “The Music Box” represents Laurel and Hardy at the height of their comedic powers, offering perfectly crafted slapstick that is still hilarious 90 years later. It was honored shortly after release with an Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film according to Cinema Axis, and was included in the National Film Registry in 1997.

Miss: A-Haunting We Will Go (1942)

Just as simplicity tends to aid good comedy, overcomplication often hinders it, as evidenced by the little-loved 1942 Laurel and Hardy caper “A-Haunting We Will Go,” an overwritten feature that, while not especially difficult to follow, does contain enough overlapping plot elements that the movie seems to forget what the viewers are watching for: the comedy.

At Laurel and Hardy Central, the critic John V. Brennan argues that there is only one truly Laurel and Hardy-esque comedy moment in the entire film, a gag involving Ollie being hit twice by the same falling sandbag half an hour into the film. “A-Haunting” was one of the first movies Laurel and Hardy entered into after leaving Hal Roach Studios for 20th Century Fox, and, as Brennan argues, it is as though the duo’s new studio is uncertain of how to sustain the old Stan and Ollie magic for the duration of a feature; instead, the film is crammed with other elements, not least the presence of the then-famous performer Dante the Magician, who got second billing on the movie posters. However, like Laurel and Hardy, the respected illusionist gets very little screen time in which to ply his trade, with far too much of the movie taken up with the doings of various anonymous gangster antagonists.

Hit: Sons of the Desert (1933)

Ask any fan their favorite Laurel and Hardy feature and, if they don’t say “Way Out West,” they are almost certain to say “Sons of the Desert,” a wildly entertaining farce that, in recognition of its containing all the best Laurel and Hardy tropes, Time Out describes approvingly as the most “typical” film of the Boys’ career.

The movie sees Stan and Ollie as two members of the “Sons of the Desert” fraternity, a lodge reminiscent of the Freemasons (though Homeland to Hollywood cites the Shriners as a closer source of inspiration). Having unwisely taken an oath to attend the lodge’s convention in Chicago — without informing their spouses — the pair then undertake a campaign of deceit in an attempt to make it to the event without their wives’ knowledge. Featuring a cameo by fellow Hal Roach Studios stalwart Charley Chase as a fellow convention-goer, “Sons of the Desert” is packed with tight dialogue — Stan runs rampant with memorable malapropisms throughout — and great visual gags.

As an indication of the love that the movie enjoys among fans, it is worth noting that its title has since been adopted as the name of the International Laurel and Hardy Society, which is “devoted to keeping the lives and works of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy before the public,” according to its official website.

Miss: Nothing But Trouble (1944)

It seems that the more outlandish the storyline of a Laurel and Hardy script is, the weaker the overall results. In “Nothing but Trouble,” the Boys, working as a chef and butler for an eccentric woman, become friends with a young boy, who they then discover is the exiled king of the fictional land of Orlandia. On learning he is a king, their friendship comes to resemble something like feudal devotion, with the thrust of the plot revolving around the duo protecting the young king from a would-be poisoner while also trying to fulfil their duties as hired help.

Critical commentary at Laurel and Hardy Central highlights the dearth of gags in a film that the trailer promises is “Nothing But Laughter,” and condemns both the characterization of the child king and the performance of the actor who dubs his lines (that’s right — the king’s lines are dubbed by another actor, an old trick which makes the movie especially unwatchable today). But Laurel and Hardy’s own performances are equally stilted, thanks to the movie’s glacial pace and tired dialogue.

Hit: Brats (1930)

One of the most memorable of Laurel and Hardy’s early shorts, “Brats” is based around a simple plot — “Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy remained at home to take care of the children … Their wives had gone out for target practice,” reads the original title card — executed through a hilarious visual gag: that Laurel and Hardy double up to portray their own children, whose boisterousness and talent for drumming up chaos mirrors that of the duo themselves. Per the critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, the effect is achieved through the use of double sets: one at a regular scale for the fathers, and another using oversize furniture to achieve the sense of diminished size for Laurel and Hardy Jr.

But this central device isn’t all that “Brats” has to offer. What separates the great Laurel and Hardy movies from their inferior ones is demonstrated in the opening scene of “Brats,” a dialogue-free two minutes showing the final stages of a game of checkers between the two adults that gets its laughs entirely through characterization; the “mini” Laurel and Hardy have yet to be introduced. When they are, the subtly more infantile versions of trademark Laurel and Hardy reactions — Stan’s typical crying becoming closer to full-blown bawling, Ollie’s usual anger veering closer to tantrum territory — are alone worth giving “Brats” 20 minutes of your time.

Miss: Air Raid Wardens (1943)

Set in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, “Air Raid Wardens” sees Stan and Ollie as the owners of a failed bicycle shop who decide to enlist in the war effort but are roundly rejected by all arms of the military. On returning to their shop, they find that the property has been leased to a radio salesman — who, though friendly enough to allow Laurel and Hardy to share the space with him, turns out to be a German spy. As even these opening plot points show, “Air Raid Wardens” is Laurel and Hardy’s most overt war film, the themes of which, though perhaps necessary for the age in which it was released, tend to overshadow the comedy for modern audiences. As John V. Brennan notes, this MGM production fails to play to the strengths of its leading men, and never quite recreates the magic that made Stan and Ollie stars in the previous decade.

According to the AFI Catalog, the movie also had trouble offscreen, with MGM coming under fire from the U.S. government who argued that “Air Raid Wardens,” released during wartime, undermined the role of the Office of Civilian Defense, and that its workers, having seen themselves portrayed in a comic manner, would be less likely to take their duties seriously. As a result, the script was heavily edited, rendering the final cut of “Air Raid Wardens” more toothless than it might have been.

Hit: The Flying Deuces (1939)

“Do you realize that after I’m gone that you’d just go on living by yourself? People would stare at you and wonder what you are? And I wouldn’t be here to tell them?” So goes Oliver Hardy’s reasoning that if he, heartbroken and pining after a woman who has rejected him for something else, should jump in the river and end it all, that Stan Laurel better take the plunge with him, a rare meta moment in the Laurel and Hardy oeuvre acknowledging that they, like us, can’t imagine the duo ever-existing apart.

As in their other great movies, it is the pair’s loyalty to one another that drives the story just as much as the friction between them generates the best gags. Instead of jumping in the river, Ollie is instead convinced to join the Foreign Legion, “to forget” the woman he’s pining for — and of course, Stan comes right along with him.

While the critics of Laurel and Hardy Central are right in claiming that the gags are a little thinner on the ground than some of their earlier features, the movie is certainly one of the duo’s most action-packed and drama-filled, with jailbreaks, firing squads, and plane crashes all appearing in just over an hour of run time. Crucially though, “The Flying Deuces” is also one of their biggest-hearted comedies, and remains highly watchable.

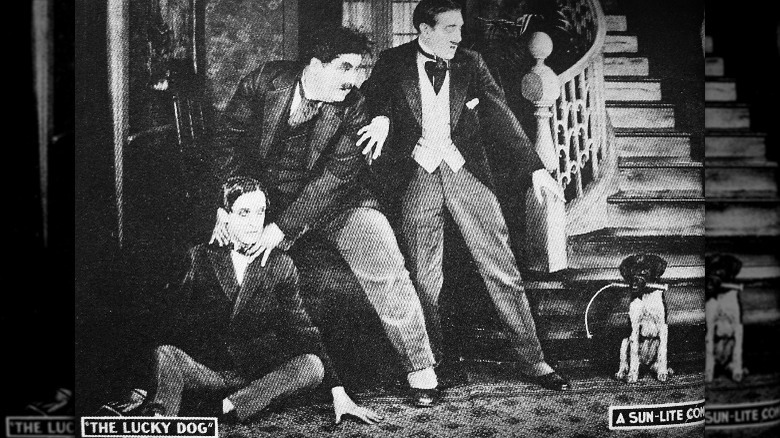

Miss: The Lucky Dog (1921)

This early silent short remains prominent in the Laurel and Hardy filmography for one understandable reason: that “The Lucky Dog” contains the first instance of the iconic duo appearing on camera together. Because of this, the film is certainly of historical importance, and it is genuinely interesting to bear witness to the origin of what would become the greatest comedy pairing of all time. But as an entertainment — which the best Laurel and Hardy works still are today — “The Lucky Dog” has little to recommend it for today’s audiences.

In it, Stan Laurel plays a down-and-out young man who befriends a stray dog, which in turn leads him into a relationship with a poodle-owning young woman, all the while having to avoid pitfalls laid out for him by the woman’s jealous ex-boyfriend and an armed robber, played by Oliver Hardy. It is fun to see Stan’s joyous friendship with the dog, but being a product of its time the pacing is slow, and neither Stan nor Ollie resemble the personas that would later make them world-famous. According to Laurel and Hardy Central, “The Lucky Dog” is, at best, a “fascinating curio” for hardcore Laurel and Hardy fans.

Hit: Block-Heads (1938)

Unlike Laurel and Hardy features released during World War II — which typically feature Nazis and the ongoing war effort as plot devices with little wit or ingenuity — “Block-Heads” begins in wartime with an eye on setting up an exquisite joke that couldn’t work any other way. The movie begins with Stan and Ollie in the trenches of World War I, with the two separating as Stan is ordered to guard the trench while Ollie and his unit head “over the top.” Proving himself to be a perfect soldier, Stan continues to guard the trench unquestioningly, as 1917 becomes 1918, and, unknown to Stan, the war ends. In fact, Stan keeps guarding his trench for a full 20 years until he is finally rediscovered and relieved of his duties.

The absurd premise is amusing in itself — and of course, audiences could imagine the character of Stan doing such a thing — but the beauty of the gag is that it sets up the pair’s inevitable reunion. Ollie, believing that Stan has lost a leg, goes through pains to care for his old friend, and the result is a slow-building but hilarious set piece involving the two talking with fond, never-before-seen courtesy even as Stan cannot help but generate slapstick moments at Ollie’s expense, all while the audience waits for Ollie’s final realization that Stan has his leg after all, and the duo’s slow descent into their old tit-for-tat interplay — a subtle but rewarding joke for their fans.

In a 5-star review for the Guardian written in 2015, the film critic Peter Bradshaw calls the film a “gem,” while at Laurel and Hardy Central John V. Brennan describes “Block-Heads” as “the last completely great movie [Laurel and Hardy] would ever make.”

Miss: Putting Pants of Philip (1927)

A hundred years on from Laurel and Hardy’s silent film career, we may argue over how much comedic cache the word “pants” still has. Some comedy fans might say we have moved on and grown more refined in our collective tastes; others would make the argument that, at heart, we as a society are as gleefully childish as we ever were.

However, most of us would likely agree that we have moved on from broad comedy based on national identity and stereotypes, which is the kind of gag that underpins this silent Laurel and Hardy short, in which an uncle — played by Oliver Hardy — discovers that the Scottish nephew (Stan Laurel) he has come to meet on his arrival via ship in the U.S. is, to the amusement of the dock’s gathered crowds, wearing a kilt. He soon loses his underwear … with the title in mind, you can probably write the rest yourself.

As noted by AllMovie, “Putting Pants on Philip” is of interest to fans as it is the first movie Laurel and Hardy put out after they had officially come together to form a double act. However, neither performs in the persona they became famous for, and the plot is somewhat cringeworthy by today’s standards.

Hit: Babes in Toyland (1934)

Based on the 1903 stage musical by Victor Herbert, “Babes in Toyland” — also widely known as “March of the Wooden Soldiers” — is one of the more unusual movies in the Laurel and Hardy filmography, but arguably their most enduring. As described by Britannica, the Hal Roach-produced feature is a fantasy set in a fictional “Toyland” populated by characters such as Little Bo Peep and Mother Goose, with Laurel and Hardy — recognizable in their mannerisms and interplay while dressed in twee attire — taking the roles of “Stan Dum” and “Ollie Dee.”

But rather than a vehicle for Stan and Ollie’s comedy alone, “Babes in Toyland” is an extravaganza, with lavish sets, regular extended music numbers, and a cast of characters enjoyable on their own terms, with Laurel and Hardy just one of the movie’s many successful elements.

As film scholar Barry Snyder explains (via Media Factory), “Babes in Toyland” wasn’t an immediate smash on its release in 1934, but instead had an unexpected afterlife as a classic holiday movie after repeat airings in the 1960s. An all-round enjoyably family film, its retro appeal remains undiminished and looks likely to continue attracting audiences even today.

Miss: Atoll K (1951)

When movie stars as prolific as Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy find themselves in development hell, you know that the movie in question is doomed to fail. And so it proved with 1950’s “Atoll K” — also released as “Utopia” and “Robinson Crusoeland” — a sad failure that also happened to be the final film of the duo’s incredible career.

As Laurel and Hardy Central describes, by 1950 the classic comedy team’s fortunes were fading in America. They had not starred in a feature in five years, since the release of their poorly-received “The Bullfighters,” and the aging comedians had instead taken to the grueling live tour circuit, mostly in Europe, and it was from there that they finally received an offer for a movie. However, the production was beset by many challenges that meant filming dragged on for nearly a year — it had been planned to last only a few weeks — and in that time both Stan and Ollie struggled with serious health problems. Laurel in particular looks shockingly unwell in the movie’s final cut, so much so that his appearance is a distraction for audiences who find themselves ignoring the comedy — what little there is — through an unshakeable concern for the actor’s health.

There is little to redeem the film, except for the admiration it might evoke for its two leads whose professionalism and desire to entertain saw them take a final swing and create one last great laugh for us all to enjoy. Thankfully, by this point, their legacy had already been secured, so that a century down the line we still find ourselves rediscovering the classics, and the many fine messes they got themselves into for our entertainment.

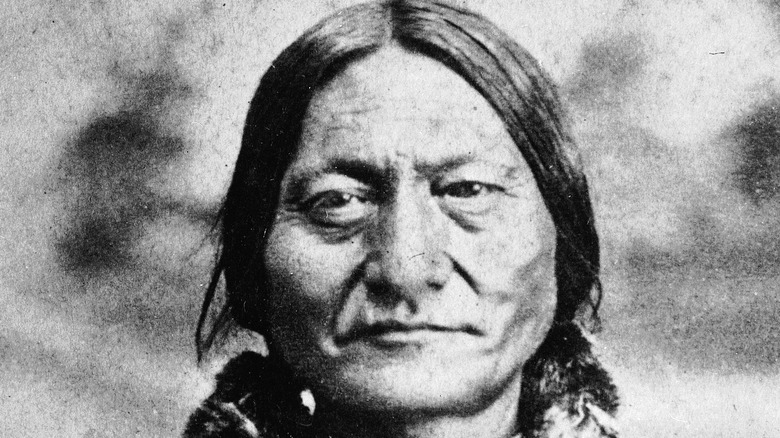

The Tragic Death Of Geronimo's Wife And Children

How Jeans Led To The Start Of Butch Cassidy's Life Of Crime

Most Dangerous US National Parks

The Messed Up Truth About Cult Leader Ron Lafferty

The Deadliest Flood In History That No One Talks About

The Real Reason Chicago Didn't Play At Woodstock

A Look At Vincent Van Gogh's Love Affair

Here's Why Alexander Hamilton And Aaron Burr Really Dueled

The Untold Truth Of Davy Jones From The Monkees

This Is Angus Young's Favorite AC/DC Song Of All Time