The Heroic Story Of The Island That Inspired The American Revolution

People are rarely willing to die for seemingly lost causes. Yet between 1729 and 1769, the people of Corsica mounted a heroic independence struggle against Europe’s established powers in defense of their lands, their families, their republic, and their constitution, the oldest in the modern world. In some cases, armed with little more than their courage, these hardy islanders, between 1729 and 1769, became the torchbearers of liberty, preferring death or exile to surrender.

Referencing this struggle in their song “1769,” the group Diana di l’alba sings, “I dreamt of a bridge and saw a young lad. On his forehead written REBEL in blood he had. It was May 1769.” Even when expressed lyrically, you know this fight for freedom was badass.

Although the revolution was ultimately extinguished, Corsica’s sacrifices were not in vain, and the dream of constitutionalism did not die. It would instead resurface on a new continent and inspire a colorful band of intellectuals, tax protestors, and patriots to create the United States of America. This is the little-known and fascinating story of how a small, seemingly insignificant island wrote its name in the history books with the blood of its people.

Early Modern Corsica

The reputation of Corsica is a violent one. From Roman times to the 20th century, the island was seen as a backwater of barbarous tribes, feuding clans, and violent mafias tucked away behind inaccessible mountains. Roman writer Seneca allegedly summed up the Corsican’s four “virtues” as revenge, robbery, deceit, and sacrilege. According to historian Dorothy Carrington, Corsica was “notoriously poor,” and riddled with vendettas between different clans. This island was the last place anyone would expect to find the beginnings of constitutional government or anything else of significance.

The island’s poverty and ruggedness of its inhabitants did have positive aspects. Although “The Geography of Strabo” called Corsicans uncouth barbarians, the Greek geographer noted their fierce love of independence and liberty, frustrating conquerors through constant brigandage and insubordination. This spirit could be harnessed for good, such as arts and culture, or for national liberation, as Richard Boswell recorded in 1769.

Medieval Corsica had two more features that distinguished it from the rest of Europe. Corsica was a Genoese possession from 1347 onward. Genoese mismanagement had created a hatred of the Italian republic that crossed social classes in Corsica. Second, Corsican society was already egalitarian. According to historian Ferdinand Gregorovius, the Corsican saw human equality as something natural. While this may be an exaggeration, Corsican nobles were relatively poor and elected institutions governed many of the towns. Under these circumstances, it was possible that Corsica could become the center of a radical new experiment in self-government. Once the Corsican upper classes were exposed to new ideas while studying in Italy, this possibility became a reality.

The Rebellion of 1729

Genoese dispossession of Corsica’s inhabitants through heavy taxation reached a breaking point in 1729. James Boswell records a hagiographical story claiming that a Genoese tax collector attempted to collect the equivalent of five pence from a poor old woman that could not satisfy the demand. After he abused her, despite her pleas, villagers pelted him with stones. Ferdinand Gregorovius gives a slightly different version. An old man was missing half of his taxes owed. When he was threatened with death, he berated the tax collector and then ran through the town shouting, “Long live liberty! Long live the people!”

This relatively minor incident (if true) began Corsica’s march towards modernity, on which it would drag the rest Europe. Genoa sent troops to the island, and a rebellion began in earnest. The Corsican people, according to Boswell, “so often glowed by an enthusiasm for liberty,” fought back under a leader named Giacinto Paoli.

The initial rebellion was a success. The Republic of Genoa was far past its zenith and was forced to call on Holy Roman Emperor Karl VI. The emperor sent soldiers from Milan and Württemberg, which stalemated the rebels, but could not defeat them. The first Corsican rebellion ended with a temporary peace in 1732. Genoa kept Corsica but conceded the island greater autonomy. In return, Corsican leaders were sent as hostages to Genoa and eventually went into exile after the Genoese tried to kill them. The peace did not last, and the fighting quickly resumed, leading to one of the stranger incidents in Corsica’s history — the debtor-kingdom.

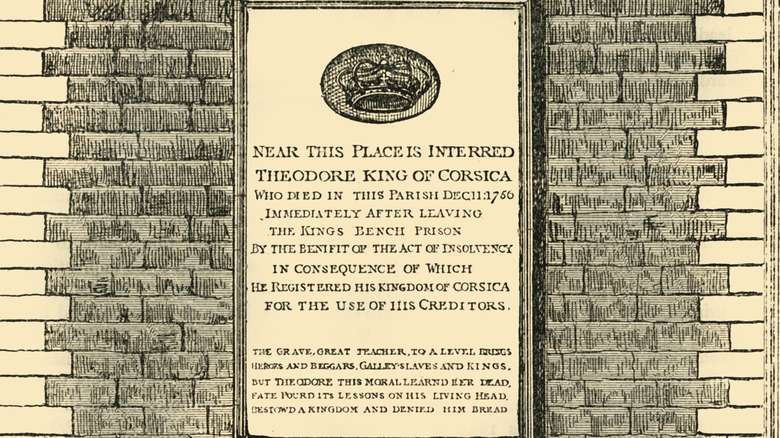

The failed adventurer-king

Corsica needed legitimacy to gain recognition from other European states. In Early Modern Europe, one way of achieving legitimacy and status was by having a king, ideally from a well-recognized dynasty with marital ties to the larger powers. Corsica never drew the interest of any of Europe’s great dynasties, but it did have a brief and farcical flirtation with monarchy.

In March of 1736, the Bey of Tunis recognized Corsica and helped German noble adventurer Theodore von Neuhoff reach the island. Neuhoff somehow convinced the Corsican notables to declare him king, despite his obscure background and sudden appearance. As king, Theodore created a Corsican court, elevating rebel leaders to nobility, issuing coins, and giving Corsica a semblance of order, although the island remained divided and poor. However, Genoa had called in its powerful French ally, whom Theodore could not defeat. The king left Corsica to find help in November.

Theodore travelled to the Netherlands, where he was tossed into debtor’s prison in Amsterdam. After his release, he returned to Corsica with a contingent of Dutch troops and some loans. These men, however, balked at fighting the powerful French army and deserted. Neuhoff later courted Britain but was promptly tossed into a debtors’ prison in London. Sir Walter Besant records that he mortgaged Corsica (which he did not own) as collateral, but never reclaimed his throne. Corsica’s leaders would have to fight on their own. As a result of his failure, however, several Corsican leaders, including Giacinto Paoli, went into exile under French orders.

1746: The turning point

After nearly 20 years, Corsica’s status was still unresolved, despite Imperial, French, Papal, Spanish, and Genoese military and diplomatic interventions. The utter failure of the Corsican monarchy probably embarrassed the rebel leaders, but they did not give up. In 1746, Corsican patriot Gian Pietro Gaffori united the disparate rebel forces under one banner and declared independence again.

With the fractious Corsican clans united under his leadership, Gaffori drove Genoese forces from the island, cornering them in several coastal forts. During the siege of Corte, the Genoese commander allegedly bound Gaffori’s son to the wall as Corsican cannons were firing. Gaffori continued the bombardment, such was his fervor for Corsican independence. Corte fell and his son was miraculously unhurt.

Occupying French forces had fallen out with their Genoese allies and offered to mediate the conflict in Corsica’s favor. Gaffori’s dreams were cut short though when he was assassinated in 1753, possibly as the result of a vendetta or on Genoa’s orders, per historian Carlo Bitossi. A five-man council took over, and the Corsican independence project risked collapse without a strong leader. Corsica needed a hero, and in 1754, it found one, under whom the island would cement its place in history.

A hero rises

Recognizing the risks of infighting within the council of five, the Corsican notables vested power in one man. His name was Filippo Antonio Pasquale de Paoli, the son of former insurgent Giacinto. Following the first rebellion, Giacinto and Pasquale had fled to Naples, where Pasquale imbibed Enlightenment philosophy while serving in the Neapolitan army. His education would play a central role in the birth of a new nation.

Associated with names such as Locke, Rousseau, Voltaire, and Montesquieu, Enlightenment rationalism emerged in Europe as a response to the bloody religious wars of the 17th century, per the University of Idaho. Favoring rationality over divine revelation, the Enlightenment resulted in core doctrines of Western government today. Chief among these was the idea of self-government with the consent of the governed. Another was nationalism, which proposed states made up of citizens sharing language, culture, and history instead of multi-ethnic empires whose inhabitants were subjects of monarchs.

Paoli’s arrival on the island proved fortuitous. At Sant’Antonio della Casa Bianca, Paoli was invested as general of the nation, and Corsica’s first president. His forces kept the Genoese bottled up while he focused on building a proper state based on these two Enlightenment principles.

The republic is born

Paoli had broken with precedent and established history’s very first constitutional republic based on the Enlightenment principles. Paoli’s most important task was to unify Corsica internally around a common language and culture. The divisions among the Corsican clans and notables had nearly cost the island its independence once, so he needed viable national institutions to curb the vendettas and unify the island. Although not as glamorous as titles of nobility and an opulent court, they were critical to forging a new nation.

From the capital of Corte, Paoli established Corsica’s identity and institutions. Italian was declared the country’s official language alongside its close relative Corsican. Although the Enlightenment tended towards anti-clericalism, Paoli was more measured than later French revolutionaries. Recognizing the importance of the Catholic faith to Corsica’s people, culture and traditions, the Corsican government chose the Marian hymn “Dio vi salvi Regina” as the national anthem and did not persecute the Church. The clergy, many of whom supported independence, returned the favor, helping establish and staff the University of Corte and a national school system. The rapid creation of these institutions was incredible, but they were second to Paoli’s biggest achievement in 1755.

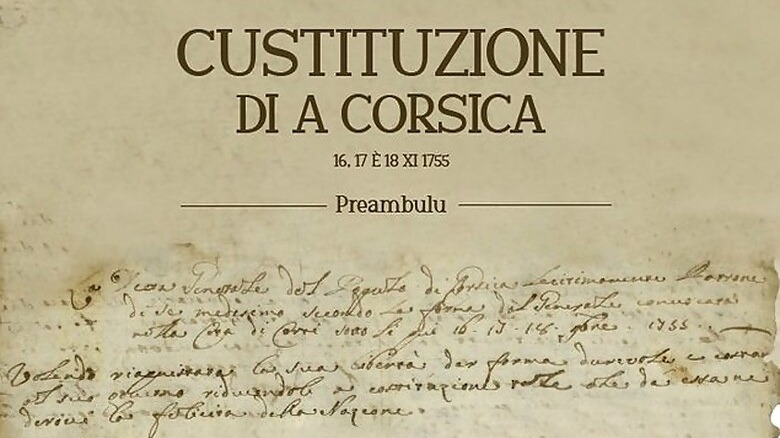

The Constitution of 1755

In 1755, Paoli drafted the world’s first modern constitution. This 10-page document written in Italian declared the intention of the Corsican Diet, “its own sole legitimate master” to “give a permanent and durable form to its government, transforming it into its own constitution to assure the happiness of the nation.” This radical rejection of divine right and absolutism ushered in an exciting new era of constitutional experiments. It is impossible to describe the complexities of the Corsican constitution succinctly, but Carrington noted its more salient features.

The Corsican Republic had extensive suffrage. All men over 25 were allowed to vote for representatives to the diet or serve in it regardless of social class. Women could vote in local elections for mayors. Only the democratically elected diet could pass laws: Ruling through executive fiat was forbidden. The executive branch consisted of a council of state of about 142 rotating members) in addition to Paoli, the president. This body concerned itself with national defense, in part with foreign relations, and with the judiciary. The nation’s highest court was composed of four judges, although local judicial bodies made decisions independently. Sentences or fines under 100 lire were final, but more severe verdicts could be appealed if the defendant protested his innocence.

Although the Corsican constitution was not perfect, the diet had the crucial power to amend it. The diet also had the power to remove the president through a vote and replace him, providing a primitive system of checks and balances that sadly was never given time to develop. Despite anti-democratic provisions, such as clerical representation and an imperfect judiciary, Corsica, tiny island of 94,000 people, had become the first-ever country (at least on paper) to guarantee full equality under the law.

The infamous sale

Although Corsica had achieved de facto independence, it only drew recognition from the Bey of Tunis. Everyone else still recognized Genoese sovereignty over the island. The Italian republic was by now crippled by debts to pay for the various forces it had contracted to quash the Corsican rebellion. According to the Institute of World Politics, the Genoese Senate faced French demands for repayment of its debts over aid rendered over the course of the Corsican war.

Facing bankruptcy, the Genoese Senate unanimously voted to sell Corsica to France in lieu of repayment. According to Gregorovius, the 1768 Treaty of Versailles finalized the sale, which the German historian eviscerated as illegitimate and immoral. But morality takes a back seat in matters of money and war, and Corsica officially became part of Louis XV’s France. Paoli now faced one of Europe’s most powerful and well-equipped armies, while Boswell noted that Corsica’s regular army consisted of a mere 500 men.

Paoli was an admirer of the Roman Republic. According to Gregorovius, the Corsican president believed that Rome fell the moment it created a paid, professional army. Paoli believed that every male citizen (and in practice, even some women) was a soldier and fought best in defense of his liberty. In a letter to the clergy, Paoli personally tasked communities with organizing their own militias, giving every Corsican male the right to bear arms and the duty to know how to use them. Buoyed by national enthusiasm, the Corsican citizen army shocked the world by routing the French at Borgo.

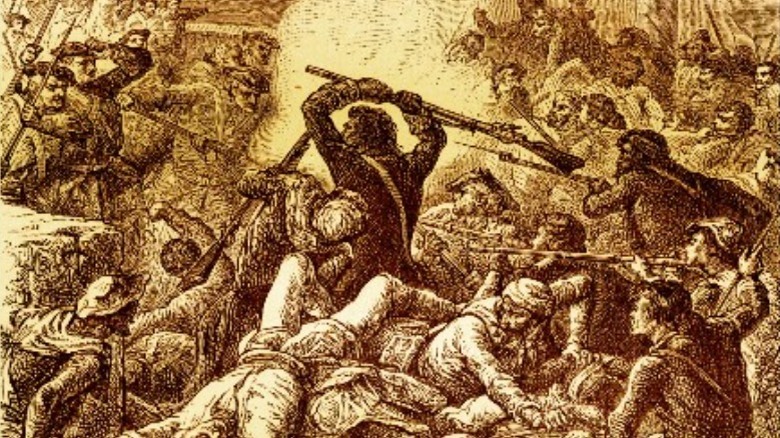

Ponte Novu

Paoli’s citizen army, despite its ill-discipline and lack of equipment and experience, had repelled one of Europe’s most powerful armies. A furious Louis XV sent Noël de Jourda, Comte de Vaux with 15,000 men to crush the Corsicans. From Bastia they marched towards Corte. According to Thomas Forester, the French bribed one of Paoli’s commanders to stay back, allowing de Vaux to outmaneuver the Corsicans. Paoli withdrew to Ponte Novu, a Genoese bridge on the Golo River, where he hoped to funnel the French and negate their superior numbers and equipment.

Paoli set up headquarters at Rostino and went to raise more men, leaving the defense of the bridge to Carlo Saliceti. According to Paul Antonini, Saliceti’s men attacked the French at Lento on May 8th, but French artillery drove them back. The Corsicans retreated in good order to defend the bridge.

As the Corsicans approached the bridge, reinforcements from the right bank joined them. According to Voltaire (quoted in History Today), the Corsicans doggedly defended the crossing behind a human rampart of their dead. It was ultimately a lost cause. The French had taken the heights to the west of the bridge and shelled Corsican forces while charging them from the front. As casualties mounted, Saliceti ordered his men back across the bridge to regroup on the east side of the river.

The republic is crushed

At this point, disaster struck. Paoli had hired a Prussian mercenary company to guard the east side of the bridge. As the retreating Corsicans approached their own lines, the Prussians fired upon them. Sensing treason, the Corsican army disintegrated before the French advance as Paoli watched in horror. The Prussians’ motive at Ponte Novu rests on Voltaire’s claims. Forester writes that the Prussians fired on the pursuing French, accidentally hitting their Corsican comrades. However, if the Corsicans had been fighting at the bridgehead, it is impossible that the Prussian forces could have accidentally and continuously fired on their comrades, who did not suddenly charge the bridge, unless they had been paid to do so. Regardless, the struggle was over.

Saliceti rallied the remnants of the army and harried French forces but was unable to stop them from reaching Corte, although he made them pay dearly. Some Corsican commanders and local potentates, such as Carlo Maria Buonaparte, surrendered to the French to protect their families. Paoli, Saliceti, and other die-hards became hunted fugitives. On June 12, 1769, Paoli dissolved the Corsican army and fled to England via Livorno, with his loyalists, where he died in 1807.

Although Paoli briefly governed a constitutional Anglo-Corsican Kingdom in 1796 under British auspices, he was never able to re-establish his beloved Corsican Republic. However, Corsica had not fought in vain. True liberty required sacrifice and risk of death. Inspired by these actions, the torch of liberty passed to another determined group of patriots in the New World.

The American Dream is born

Across the Atlantic, Patriots in the Thirteen Colonies eagerly followed the Corsican War. According to the Journal of the American Revolution, Corsica’s heroism made Paoli highly respected in America, inspiring the Patriots (especially the Sons of Liberty) to push for a war of independence. William Pitt called him “a hero out of Plutarch.” According to the Colonial Society, the leader of the Boston Riots, Ebenezer Mackintosh, named his son after Pasquale. At Columbia University (then King’s College), a battalion of student volunteers of the NY militia nicknamed “the Corsicans” formed in 1775. Its most famous member? Alexander Hamilton.

Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Wisconsin all contain towns named Paoli after that famous Corsican hero. At Paoli’s Tavern, PA, British forces defeated George Washington and Anthony Wayne. The significance of the name was surely not lost on either side. But was Paoli’s spirit present at the Old Pennsylvania State House in 1787?

According to Thomas Jefferson, he was not. The US Constitution was a purely American product, free of foreign influence. But Georges Coanet, secretary-general of the Pasquale Paoli Foundation, during a visit to Paoli, PA, noted that Paoli ran in the same Masonic circles as Benjamin Franklin and Lafayette, so they would have at least known about his constitution and ideas. It will never be certain, but given his American fame after Ponte Novu, it is certainly plausible that Paoli was at least on the minds of some of the founders during that hot Pennsylvania summer.

Il vero Padre della Patria

Today, Paoli is known in Corsica as the Babbu di a Patria (the father of the fatherland). But he may also deserve the Italian version of the title, today held by Giuseppe Mazzini. In 1750, Paoli identified himself as “Corsican by birth” but “Italian by language, custom and tradition.” Corsica was part of the Italian brotherhood, which boasted a shared ancient heritage. The Corsican Revolution would cause “the sun of liberty” to emerge over Italy and finally bring the feuding brother-states together.

Paoli’s famous words have been forgotten in Corsica and suppressed in France for political reasons, but they attest to Paoli’s grandest vision, a united Italy. He feared that non-Italian rule would herald the death of Corsica, reducing its people, in his own words, to “nothing.” Apart from a brief Italian occupation from 1940-43, Corsica remained French through the 20th century and Paoli’s worst fears were realized. Italian, Corsica’s literary language, was banned in 1859, and definitively suppressed under Charles de Gaulle in 1943, cutting Corsica’s links with its past and heralding the thorough ongoing Gallicization of the island.

The Corsican language, per UNESCO (via CNN) is in danger of extinction. Most ethnic Corsicans have a superficial knowledge of the language from school, but speak it haltingly and with noticeable Gallicisms. Yet Paoli’s name lives on. Although forgotten in America, he continues to inspire Corsicans to fight for their heritage and history against the advances of globalization and modernity through music and politics in hope that one day, Corsica may achieve autonomy within France.

The Real Reason Catholics Believe In Purgatory

This Theory Suggests The Egyptian Pyramids Are Actual Power Sources

How A Sunken Ship Led To Ed And Lorraine Warren's Marriage

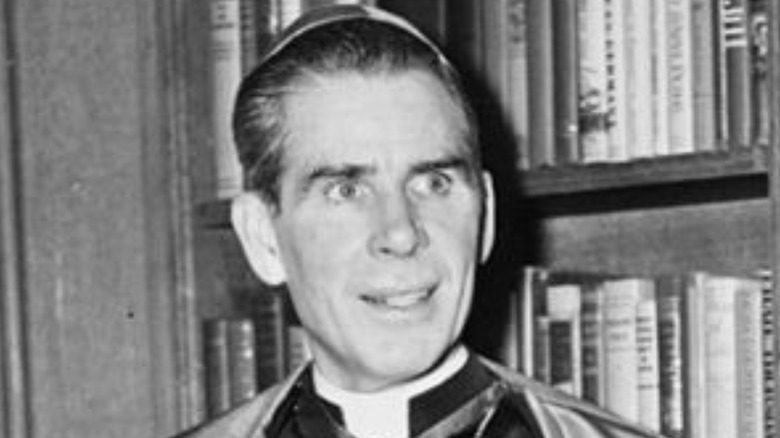

The Untold Truth Of Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen

The Tragedy Edmund Hillary Lived Through After Conquering Mount Everest

The Temptation Of Christ Explained

This Was Joaquin Phoenix's Experience In The Children Of God Cult

The History Of The Most Sacred Rivers In The World

The Myth About Pocahontas You Need To Stop Believing

Bizarre Details About Roswell That Still Don't Make Sense