The Messed Up Truth Of Inuit Identification Numbers

Having one’s name purposely mispronounced is one thing, but being assigned a number as a surname because the federal government is unwilling to learn one’s name is another level. But that’s exactly what the Canadian government did to Inuit from the 1940s to the 1980s. The system was then said to be discontinued but, in 2013, Jennifer Qupanuaq May received mail from Service Canada that referred to her using the identification number, per Vice.

In the 1970s, Project Surname was organized and some Inuit were given the chance to choose their own surname. But some still had surnames imposed upon them, and as some Inuit took on their fathers’ surnames, as they were further assimilated into a western patriarchal naming system, per CBC.

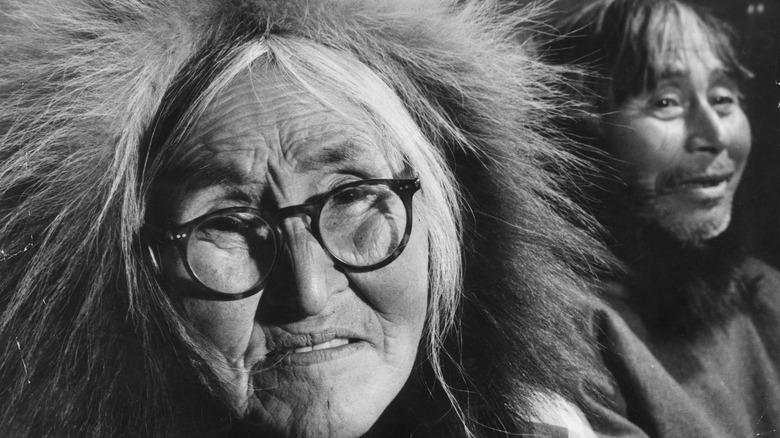

For many, the identification numbers were “an erasure of Inuit identity.” Others considered them “a brilliant government idea” to deal with the “butchery from the pens of Qallunaat” that Inuit names suffered from, per “Inuktitut.” Meanwhile, another initiative known as Project Naming is currently working with Indigenous people in Canada to identify elders in photographs that were collected and stored in the Library and Archives Canada.

A brief history of the Inuit

The Inuit are one of several indigenous cultures native to the North American Arctic region. Inuit also share the polar region with the Yupik and Inupiat of Alaska and Russia as well as the Inuit of Greenland. According to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the first Inuit territory is thought to have existed on the southwestern coast of what is now Alaska, around 6500 BCE. By 3000 BCE, the Inuit moved eastward in what is known as the Sivullirmiut, which means “the first people.” In addition to the Sivullirmiut, some stories also refer to the Tunnit as Inuit ancestors.

Groups of Sivullirmiut expanded across the north coast of the North American continent and into southern Greenland. Based on archeological finds, it’s known that the Sivullirmiut made tools such as needles and knives out of ivory, bone, and stone. Tools for hunting, such as harpoons and spears, have also been discovered, Tusaayaksat Magazine reports.

After several waves of migration, the Sivullirmiut were “either displaced or assimilated” by the Thule, who migrated around 1250 ACE, “represent[ing] the final migration out of Alaska,” according to Unikkausivut: Sharing Our Stories. Present-day Inuit culture developed from the Thule as well. Although Vikings had come into contact with Inuit since 1000 ACE, the first historically recorded interaction between Inuit and Europeans occurred in 1576.

The arrival of Qallunaat

British seaman Martin Frobisher was the first recorded Qallunaat, or non-Inuit, in Inuit territory, what is now Nunavut. And between 1576 and 1848, only about 22 explorers entered Inuit territory, according to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. But as the commercial whaling industry took off, more and more European whalers began occupying the Davis Strait in the 18th century. And with regular contact with the European whalers came waves of disease, leading to a “significant decline in [Inuit] population.”

By the second half of the 1800s, the over-harvesting of whales by Europeans “went beyond the limit of sustainability” and Inuit slowly transitioned to the fur economy, though the culture of fur trapping started to develop primarily around the 1920s.

Unikkausivut: Sharing Our Stories writes that in the 1930s, the Canadian government began removing Inuit children from their families and sending them to residential schools, although these schools existed as early as 1867. There, Inuit children were forbidden from speaking their traditional languages and practicing their culture. Day schools were also established, leading many Inuit parents to resettle in those communities. Many of these schools had a horrific reputation, with Indigenous and First Nations children being subjected to physical abuse and sexual abuse, per McGill-Queen’s University Press. As of 2021, it’s still unknown exactly how many Indigenous children died in residential schools.

The introduction of disc number

Inuit names don’t follow a patriarchal lineage denoted by surnames, and instead follow a “system of specific references to family relationships,” also known as tuqsurausiit, writes Zebedee Nungak in “Inuktitut.” And since Canadian administrators were unwilling to learn how to pronounce Inuit names, writing them off as “too long” or “too hard,” in 1941, the Canadian federal government registered each Inuk with a number, often stamped on a disc.

The Canadian government made previous attempts to create a system of identification for Inuit. A. Barry Roberts writes that in 1932 fingerprinting was used, but because of its connotation with criminality, it was actively rejected by Inuit.

Known as ujamiit or ujamik, also referred to as disc numbers or Esk*m* identification tags, Inuit were required to carry their disc number at all times, according to the Library and Archives Canada Blog. “To many, they looked and felt like dog tags.”

And although the government claimed that the goal was to make the administration of medical and social aid smoother, the disc numbers had soon completely replaced Inuit names in the eyes of the Canadian administration. Written correspondence from the government would be addressed to disc numbers, and at schools, Inuit children were called by their disc numbers instead of their names, Vice reports. And the process wasn’t even standardized until 1944, at which point the government realized that the disc numbers given out since 1941 hadn’t even been filed with their corresponding person.

Abraham Okpik and Project Surname

In 1965, Abraham Okpik became the first Inuk to be appointed a seat on the Northwest Territories Territorial Council. The following year, Simonie Michael became the first Inuk to win an elected seat on the territorial council, per Nunatsiaq News.

As they sat on the council, Okpik and Michael’s legal names were Abraham W3-554 and Simonie E7-551, respectively. And after Michael spoke up at a council meeting in 1969 about the continued use of disc numbers, the Canadian government was pressured to start Project Surname in 1970, according to Listening to Our Past. Okpik was made head of Project Surname and with a linguist, he traveled across Northwest Territories and Nunavut, giving Inuit the chance of choosing their own surnames for the first time. Project Surname ended up involving roughly 12,000 people, per CBC. But identification numbers were still being issued to Inuit as late as 1982, according to Vice.

The Canadian Encyclopedia notes that while some supported Okpik’s efforts, others thought it unnecessary to continue imposing surnames on Inuit when they don’t exist in the Inuit language. Okpik was also criticized for often conforming to patriarchal naming lineages for family names, which meant that some Inuit women “came home to find their identity overturned and reassigned.”

What Is Under The Great Sphinx Of Giza?

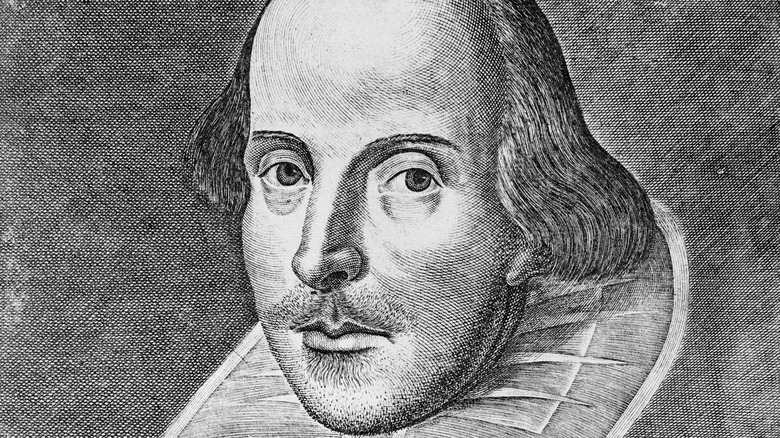

A Look At The Link Between Queen Elizabeth I And Shakespeare

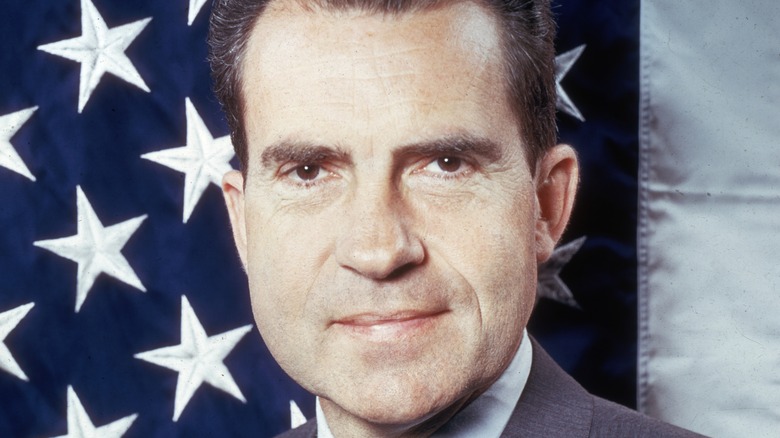

Nixon's Alleged Plot To Assassinate A Journalist Explained

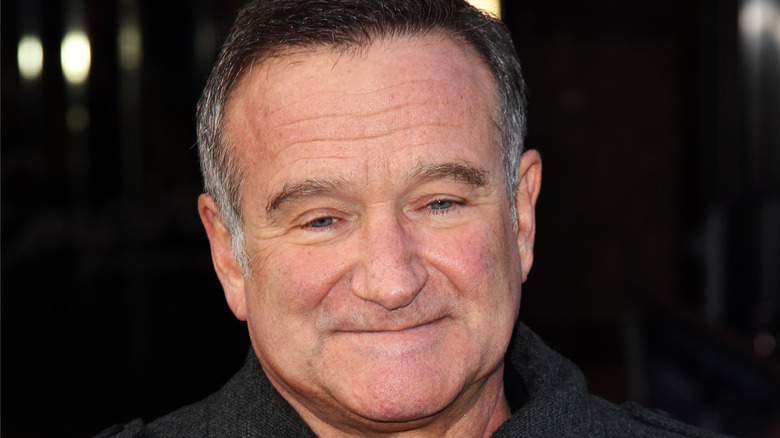

The Truth About Robin Williams And John Belushi's Relationship

This Is How Many People Died In The Pentagon Attack On 9/11

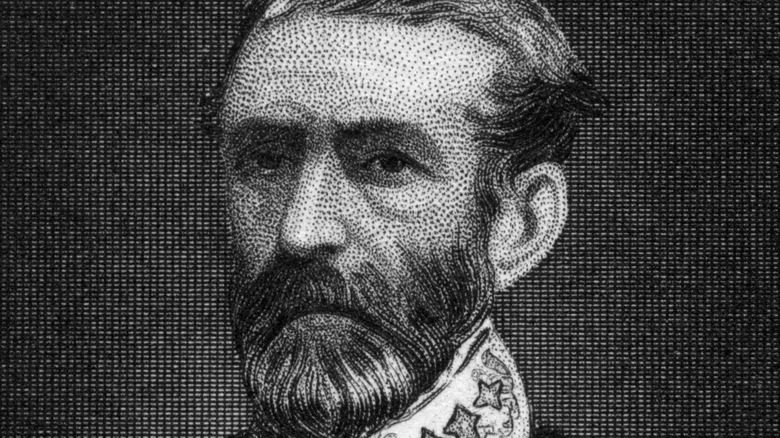

Why Braxton Bragg Was Considered One Of The Worst Generals In The Civil War

The Tragic Truth About Evita's Childhood

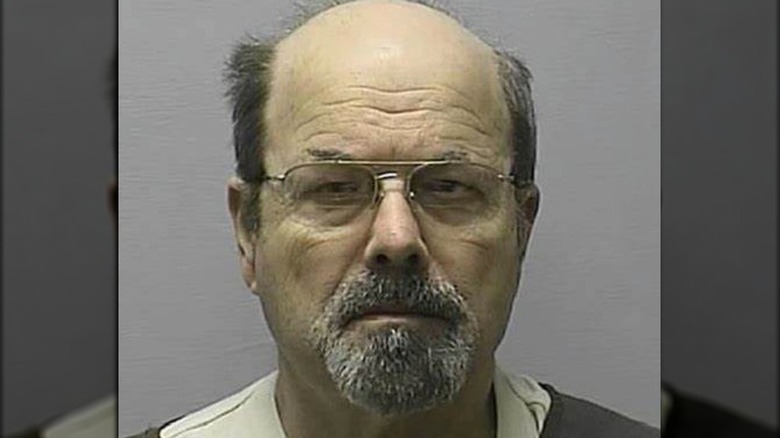

The Motivation Behind The BTK Killer's Murders

The Crazy History Of The Seven Summits Mountaineering Challenge

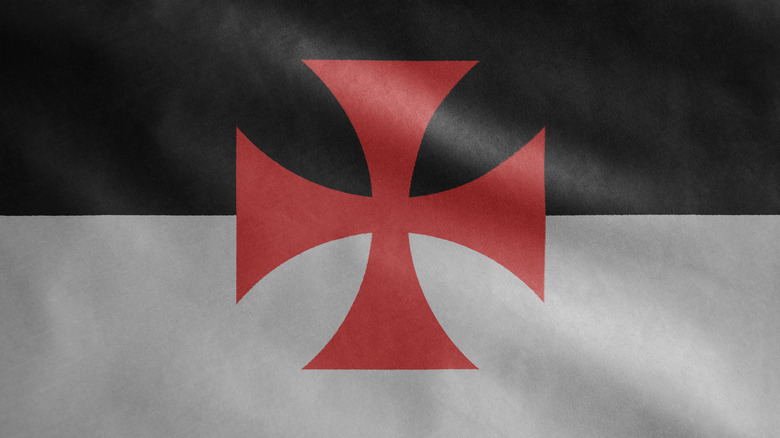

This Was The Dress Code Of The Knights Templar