What Really Happened During The 1944 Philadelphia Transit Strike?

When workers at the Philadelphia Transportation Company went on strike in August of 1944, they weren’t protesting low wages or poor working conditions. Instead, the strike was made up of over 6,000 white workers who were protesting the promotion of eight Black workers at the company.

Although the strike only last six days, it affected war production enough that the United States government had the military intervene. And with the strike’s failure, the number of Black workers at the Philadelphia Transportation Company nearly doubled within a year while the types of jobs given to them also expanded.

The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority took over the PTC in 1968. And Philadelphia Magazine writes that in 2014, SEPTA reported that Black workers accounted for 61% of the overall workforce and 35% of all agency managers. A stark difference compared to the 537 Black workers out of 11,000 in 1943. Here’s what really happened during the 1944 Philadelphia Transit Strike.

The Philadelphia Transportation Company

By 1943, the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania had a history of racist hiring and employment practices. According to the “Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-class History, Vol 1” by Eric Arnesen, Black workers were only hired for low-status positions, and weren’t allowed “to drive transit vehicles or interact with the public.” When Black workers confronted PTC’s management about this, they were informed that the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Employees Union (PRTEU) had demanded “the best jobs for whites in exchange for wages some 10% below national standards.” In Spring of 1944, PTC workers voted to replace PRTEU with the Transit Workers Union (TWU).

Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9346, which called for an end to discriminatory employment practices, per Temple University Libraries, for several months the PTC refused to promote their existing Black workers or hire any new Black workers. At the time, out of 11,000 workers, 537 were Black. Meanwhile, Black residents of Philadelphia protested for several months, holding placards that read “In Democracy, Freedom to Work Belongs to All” and “We Drive Tanks, Why Not Trolleys,” writes James Wolfinger in “Philadelphia Divided.”

Due in part to efforts by the NAACP, the War Manpower Commission mandated that the PTC had to enforce a non-racist employment policy. As a result, the PTC finally promoted eight Black workers — whose names unfortunately cannot be located as of 2021 — to being trolley car drivers. And when white PTC workers found out about the upcoming eight promotions, they decided to strike if the promotions went through.

White workers strike

On August 1, 1944, the white workers of PTC started striking. And the Global Nonviolent Action Database writes that this was against the wishes of their own union. The strike led to a citywide shutdown of the transit system and since Philadelphia was one of the largest war production sources for the United States during World War II, the strike also brought the city’s war production to a grinding halt with people unable to get to their places of work.

On August 2, James McMenamin, the spokesperson for the committee leading the strike, stated that the strike was “strictly a black and white issue” and that they would return to work if the eight Black workers were demoted back to their original positions, according to Temple University Libraries. The “Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-class History, Vol 1” also notes that before striking, white workers had discussed forming a “white supremacy movement.” Meanwhile, the PTC allowed all this to occur because they knew that with the Smith-Connally Act, which outlawed wartime strikes, this would give the government reason to get rid of the TWU, which had asked for pensions and pay increases.

A History of Racial Injustice writes that by the third day of the strike, almost two million people had been prevented from traveling and the strike had grown to over 6,000 white workers.

FDR and the military takeover

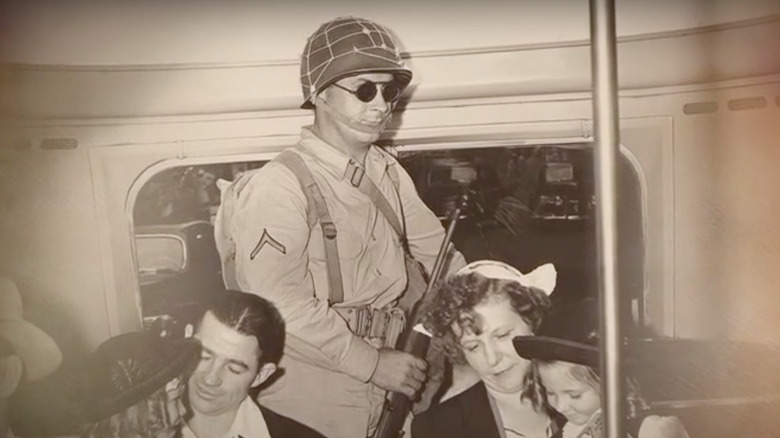

On August 3, President Roosevelt gave the Army authorization to take over Philadelphia’s transit system and end the strike. Major General Phillip Hayes also threatened to forcibly enlist any white workers who continued to strike, per Hidden City. But over 6,000 white workers voted to continue striking.

On August 5, President Roosevelt made good on his promise and up to 5,000 armed soldiers were sent into Philadelphia. The leaders of the strike, Frank Carney, James Dixon, Frank Thompson, and McMenamin, were arrested and charged with violating the Smith-Connally Act. And after being released from jail the following morning, McMenamin told the workers that the strike was over. The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia writes that army troops maintained their presence in the city for another ten days keep the peace.

The white workers ultimately ended the strike because of the threats of termination, of being unable to defer their drafts, and the loss of unemployment benefit eligibility, per A History of Racial Injustice.

The impact of the strike

By September, all of the original eight Black workers had started their jobs as trolley drivers. By the following month, there were 16 Black trolley drivers, and by the following year, there were 900 Black workers at the PTC, with positions ranging from conductors to publicity staff, per The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

The successful protest against the strike also showed that Black people could “win the support of the state, of the federal government,” according to historian Eric McDuffie, of the University of Illinois. With the work of Black activists and support from the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the 1944 Philadelphia transit strike was ultimately a failure.

However, as the Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-class History, Vol 1 notes, the Philadelphia transit strike was “only one of many hate strikes” that occurred in the United States during the Second World War. Other examples include the Packard Motor Car Company plant Hate Strike, the Sparrow Point yard hate strike, and the Curtiss-Wright plant hate strike.

How The Mob Controlled The Jukebox Industry

What Really Happened During The Red River Bridge War

This Is Where Early Humans First Domesticated Cannabis

What Was Jesus' Real Name?

The Truth About The Roman Empire's Siege On Carthage

The Ten Plagues Of Egypt Explained

False Things You Believe About Sharks

The Tragic Death Of Aaron Burr

The Tragic Death Of Alexander Hamilton's Son

Survey Reveals Which Planet Most People Want To Visit