The Untold Truth Of Ritchie Valens

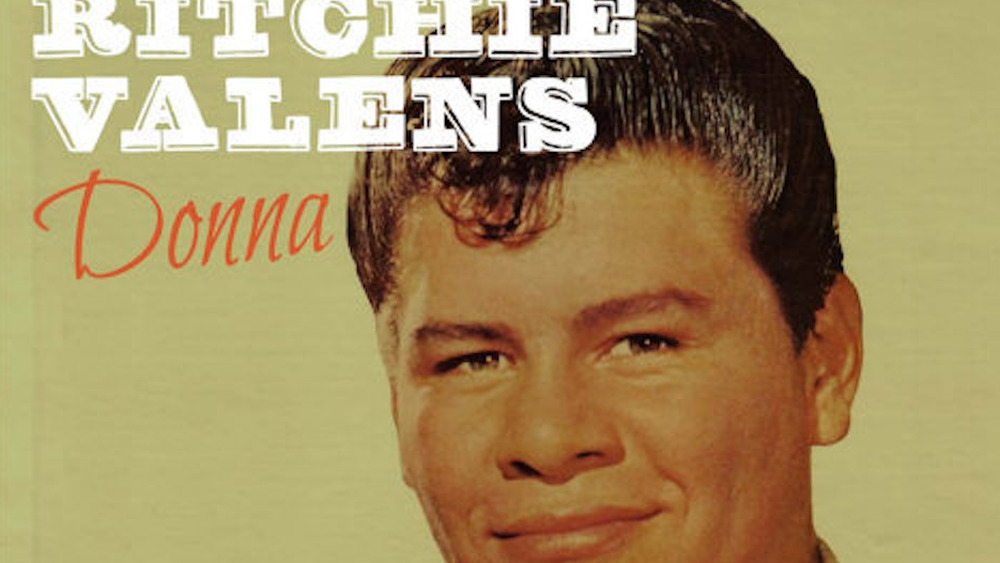

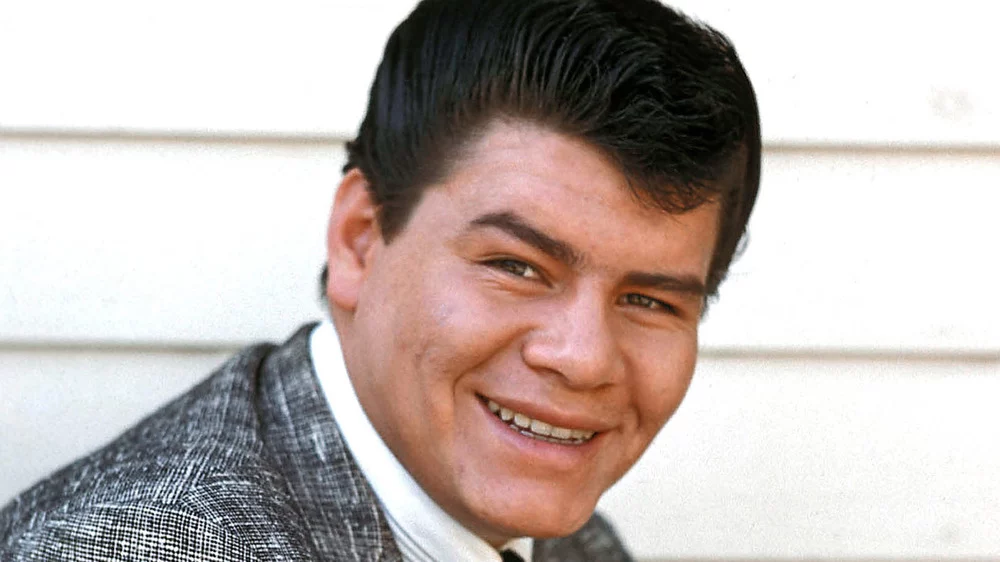

Ritchie Valens was one of rock n’ roll’s earliest and most promising stars. A pop music titan while still just a teenager, he emerged in 1958 as a talent to be reckoned with, combining a voice that was at turns soulful and peppy with a preternatural talent for playing the guitar with precision and speed. By early 1959, Valens had shown off his skills with three highly varied singles — the ultra-catchy and breezy “Come On, Let’s Go,” the restrained torch ballad “Donna,” and “La Bamba,” a shredding, blistering take on an old folk song the Mexican-American musician learned in childhood that became one of the first and biggest songs not performed in English to hit big in the United States.

Sadly, Valens is also one of music’s biggest “what could have been” stories — he died at age 17 while still a rising success. He didn’t have the chance to record all that much music, but what he did make would cement his status as an American musical legend. Here’s a look into the tragically brief life of Ritchie Valens.

Ritchie Valens was in a band before he found solo success

Ritchie Valens was just 17 years old when he scored the smash hits “La Bamba” and “Donna” in 1958, which feature his virtuoso-level guitar playing and classic crooner-style voice, respectively. To be that proficient and successful at such a young age obviously hints at Valens’ prodigy-like abilities, while also indicating that he had a bit of musical experience already.

After learning to play several instruments as a child, according to AllMusic, Valens fell in love with playing the guitar most of all, and he mastered a standard model built for a right-handed player, even though he was left-handed. Absorbing the wild stylings of early rock n’ roll, including rockabilly artists and Little Richard, along with traditional and folk forms he gleaned from his Mexican-American family, he synthesized his influences and landed a position as the guitarist in a local garage rock band called the Silhouettes. Before long, the 16-year-old Valens was the group’s lead singer, too.

Ritchie Valens had to both hide and share his cultural background

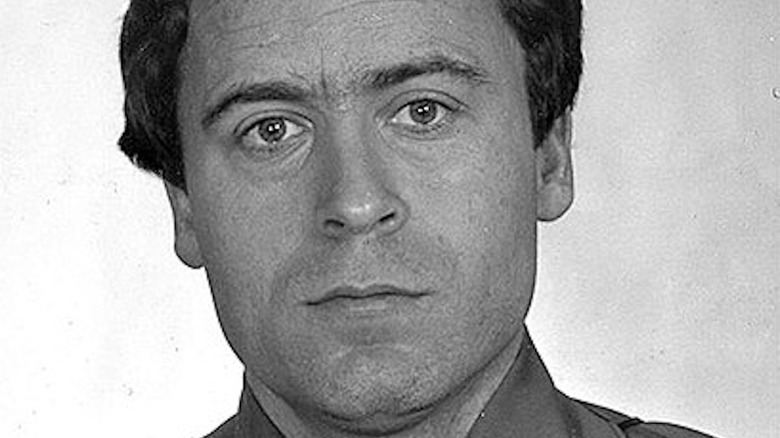

The teenager with the short but storied career in the late 1950s is known internationally and throughout history as Ritchie Valens, but that is not the performer’s real name. Born and raised in California’s San Fernando Valley by Mexican-American parents, his birth name was Ricardo Esteban Valenzuela Reyes. But because he came to prominence in the 1950s, when the cultural landscape was decidedly dominated by performers of Caucasian and European backgrounds, and people of color were relegated to less mainstream avenues, Valens had little choice but to play by the music industry’s unofficial whitewashing rules. In 1958, producer Bob Keane discovered Valens and signed him to Del-Fi, his own label, then talked the singer into shortening his name to the far less ethnic-sounding Ritchie Valens.

But for however much Keane tried to downplay Valens’ Mexican heritage, he also attempted to exploit it, because it was an angle and a perspective that most other prospective rock stars of the era couldn’t claim. Keane had Valens record a rock n’ roll version of “La Bamba,” a Mexican folk song he’d been playing on the guitar since he was a child. According to the Los Angeles Times, a family friend named Dickie Cota taught young Valens the guitar notes as well as the lyrics in Spanish, a language in which Valens was not fluent. “Ritchie never spoke in Spanish because his dad never did,” his mother, Connie Valenzuela, said.

Ritchie Valens was a two-hit wonder

In 2000, bigwigs in the music industry thought to bestow one of its most prestigious honors on the late Ritchie Valens — they voted to enshrine him in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. His impact on 20th century American music was profound and incalculable, but on paper, Valens wasn’t all that much of a commercial success. But then, he didn’t have much time with which to rack up a string of hits — he released his first recordings in 1958 and died in early 1959.

Owing to the sad circumstances of his untimely death, Valens is not one of the most prolific hitmakers in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, landing a scant five singles on the Billboard Hot 100 pop chart. His debut, “Come On Let’s Go,” peaked just outside the top 40 in late 1958, while his most familiar tune, “La Bamba,” peaked at No. 22 on Feb. 1, 1959, two days before Valens died. Valens’ biggest hit came posthumously, when the tender, English-language love ballad, “Donna,” hit No. 2 about three weeks after he passed away. A couple more minor hits in 1959 followed — “That’s My Little Suzie” and “Little Girl” — and that was all the radio would get from Valens.

Ritchie Valens turned an old folk song into a groundbreaking rock song

“La Bamba” is Ritchie Valens’ most famous musical work, but it’s not a Valens original. He did, however, come up with the arrangement of the tune as an energetic, highly crafted single emblematic of the 1950s early rock n’ roll sound. “La Bamba” is based on an old piece of folk music from the Mexican state of Veracruz. It’s an example of a son, a proto-mariachi form of musical storytelling that combines many traditional styles.

Valens learned the song as a child, and he absent-mindedly played it on his guitar one day in front of his manager, Bob Keane. “He was in the backseat strumming his guitar,” Keane told NPR. “And then I heard this melody, this ‘Dadadada da da da,’ and I said, ‘Boy, that’d make a great rock record, I think.'”

Initially, Keane didn’t think a Spanish song could be a hit, nor did Valens want to cheapen this important piece of Mexican culture by turning it into a rock song. He figured a good way to get around that would be by translating it into English, until he sat down to do it and realized that there were around 500 verses of “La Bamba” to address. Instead, he just picked a couple and recorded the song in Spanish, with a rock n’ roll arrangement. In 1959, Valens’ take on “La Bamba” became the first rock hit with Latin American origins.

Ritchie Valens' “Donna” is based on a real person

In 1959, Ritchie Valens peaked commercially and artistically with two extremely successful singles. One of them was the rollicking, hard-charging folk/rock fusion tune “La Bamba,” sung completely in Spanish.” The other was completely different — “Donna,” a sweetly crooned teen-idol type love song, performed in English, suitable for slow-dancing. The latter now ranks in the pop music canon of songs named after women, alongside Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue,” the Knack’s “My Sharona,” and Toto’s “Rosanna.” “Donna” is also about a real person, a teenager named Donna Ludwig, that Valens had dated before he found success as a rock star.

According to TheWashington Post, a heartbroken Valens put the song together in 1957 and sang it to the then 15-year-old Ludwig on the phone, shortly after they’d ended their romantic relationship. When Valens proclaimed that he had once “had a girl” named Donna but no longer did, he was telling the truth, although the general public didn’t know the song was about her until after it climbed the charts in early 1959, right around the time that Valens died. In the resulting media hubbub, an entertainment magazine published Ludwig’s address, and she received 8,000 letters a week. Meanwhile, a group called the Kittens recorded a song about her called “Letter to Donna,” and Elvis Presley asked her out on a date so that he could discuss her ex-boyfriend.

Ritchie Valens had several secret lovers

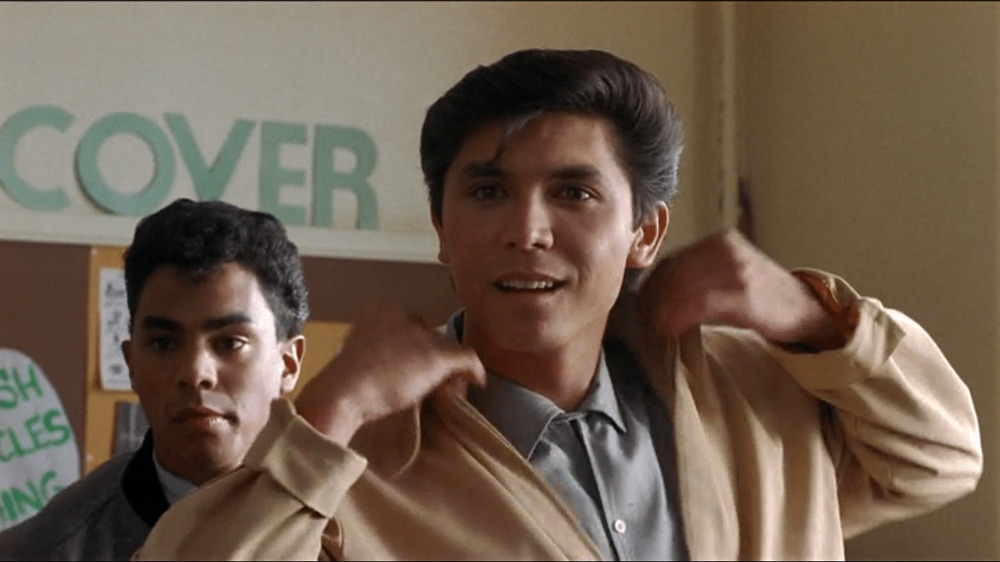

With not much public information on Ritchie Valens available between his pop chart ascent in 1958 and death in 1959, much of the collective knowledge on the late rock star comes from the 1987 biopic La Bamba. According to TheWashington Post, the film took a few creative liberties, particularly in regards to Valens’ romantic life. In the film, Valens (portrayed by Lou Diamond Phillips) is head over heels in love with girlfriend Donna Ludwig (Danielle Von Zerneck), and he records the moony love song “Donna” in her honor. However, Valens’ relatives couldn’t recall having ever met her, and the musician’s manager and champion, Bob Keane, didn’t know her very well either. “I remember Ritchie saying he’d written this song for his girl, Donna, but I never heard anything else about her.”

Ludwig asserts that she and Valens had broken up long before he became famous, leaving him free to indulge in the more carnal elements of the rock n’ roll lifestyle. According to Valens biographer Beverly Mandheim, the musician cavorted with young women during a brief tour of Hawaii, and a New York-based woman named Diane Olson attended Valens’ funeral, claiming to be his fiancée.

Ritchie Valens won a coin toss and lost his life

By early 1959, Ritchie Valens was emerging as a rock n’ roll superstar, thanks to attention-grabbing singles like “Come On, Let’s Go,” “Donna,” and “La Bamba.” He was invited to appear on “The Winter Dance Party,” a rock package tour that also featured J.P. Richardson, a.k.a. “The Big Bopper,” who’d had a hit with the spoken-sung “Chantilly Lace” and headliner Buddy Holly, best known for formative rock classics like “That’ll Be the Day” and “Oh Boy!”

The tour aimed to play 24 small venues around the Midwest in just about as many days, which the group of musicians traveled to in an unheated tour bus prone to breaking down. After a February 2 show in Clear Lake, Iowa, Holly, sick with the flu, chartered a small plane for a quick and more comfortable trip to Fargo, N.D., near the next concert site in Moorhead, Minn. Pilot Roger Peterson and Holly occupied two of the aircraft’s four seats, and the other two were intended for Holly’s backing musicians Waylon Jennings and Tommy Allsup. Richardson had a cold and talked Jennings into letting him take the flight instead of sitting through a miserable, freezing bus ride, while Allsup lost his seat to Valens — he won the coin toss.

The plane never made it to Minnesota. A few minutes after takeoff, the aircraft experienced mechanical problems and it crashed into an Iowa field. All four people onboard died, including 17-year-old Valens.

Ritchie Valens cheated death

Ritchie Valens died at age 17 in one of the most famous aviation accidents in American history — the Feb. 3, 1959, small plane crash in Iowa that also killed fellow rock stars Buddy Holly and The Big Bopper. In what could be viewed as an ominous portent of future tragedy, Valens avoided an airplane-related death two years earlier.

Valens attended school at Pacoima Junior High School near Los Angeles, which sat under a flight path. On Jan. 31, 1957, two planes collided mid-air, sending one plummeting to the ground, crashing into the junior high’s grounds. Three students were killed that day, and another 90 sustained injuries. Not among them was Valens, who was absent from school that day to attend a burial service for his recently deceased grandfather. “If we hadn’t gone to my grandfather’s funeral, Ritchie would have been out there, in the playground,” the singer’s brother, Bob Valenzuela, said in a retrospective about the film La Bamba. “My grandfather’s death saved Ritchie’s life.”

There are multiple memorials and monuments dedicated to Ritchie Valens

While he didn’t live all that long, Ritchie Valens positively impacted a countless number of people with his music and his legacy. Around the United States, several monuments and memorials dedicated to the late rock star have been erected. In February 1959, he died with Buddy Holly and The Big Bopper when their small plane crashed into a farmer’s field near Clear Lake, Iowa. According to Atlas Obscura, that’s still private land, but it’s also the site of a modest guitar statue, put up in 1988, shortly after the release of the Valens biopic La Bamba.

On the stretch of highway closest to where the plane made impact, there’s another memorial, notable for its topper of a giant pair of thick glasses, like the ones Holly wore. In 1989, Beaumont, Texas, near The Big Bopper’s hometown of Sabine Pass, unveiled a statue of its local lost figure along with one of the Bopper, Holly, and Valens together. And in 2018, the town of Pacoima — Valens grew up in the area — showed off a large mural depicting the “La Bamba” singer in his prime.

Hollywood took years to come around to the idea of a Ritchie Valens movie

The 1987 Ritchie Valens biopic La Bamba was a hit by any metric, amassing $54 million at the box office, earning a Golden Globe nomination for Best Motion Picture – Drama, and Los Lobos’ soundtrack cover of the title song hit No. 1 on the Billboard pop chart. All the same, it took Hollywood more than a decade to get on board with the project.

After Chicano musician and actor Danny Valdez released his debut album in 1973, A&M Records executives inquired about his next move, which prompted a discussion with his manager, budding filmmaker Taylor Hackford, about making and starring in a movie about Ritchie Valens. The label turned it down, citing the lack of an audience and how Valens was a forgotten figure. Valdez then attempted to do the project as a stage musical, but that fell apart.

He got another chance at a Valens movie in the 80s, after the success of his film Zoot Suit, which sent him on a half-decade quest of researching Valens and slowly securing permission from the late musician’s family. Once they did, Valdez reconnected with Hackford, who by that time had become a major filmmaker. Valdez was too old to play Valens by that point, and Hackford’s price tag was too expensive, so as a producer on the film, Valdez hired his brother, Luis Valdez, to write and direct what would become La Bamba.

Ritchie Valens' family was extremely involved in the making of La Bamba

La Bambaproducer Daniel Valdez didn’t want to make the movie without the blessing of the Ritchie Valens family. The Valenzuelas approved of the project, and filmmakers thanked them by casting several family members in small roles. According to the Los Angeles Times, Valens’ sisters Connie Lemos and Irma Padilla play farm workers in the movie’s opening sequence, while their daughters, Gloria and Kristin, play their own mothers as children in other scenes. Valens’ mother, Connie Valenzuela, had an unbilled role as “Elderly Lady at Party.”

Lou Diamond Phillips, who portrayed Valens, says a profound connection with the musician’s loved ones developed. “For me and for the family and in a very weird way and in a very sort of existential way, it was Ritchie all over again. Ritchie was there,” he told Behind the Music. Lemos added that Phillips “became Ritchie to me, for those three months.”

Valens’ family was on set a lot, and Lemos was present the night the crew shot the sequence depicting the plane crash that killed the 17-year-old rock star in February 1959. The emotional gravity of the situation led to an emotional breakdown. “She just starts trembling and she says to me, ‘Why did you go, why did you have to go, Ritchie, why did you have to go?” Phillips remembered. “And she throws herself onto me, and she’s crying, and I’m holding her and she’s just sobbing.”

Where Is Cass Elliot Buried?

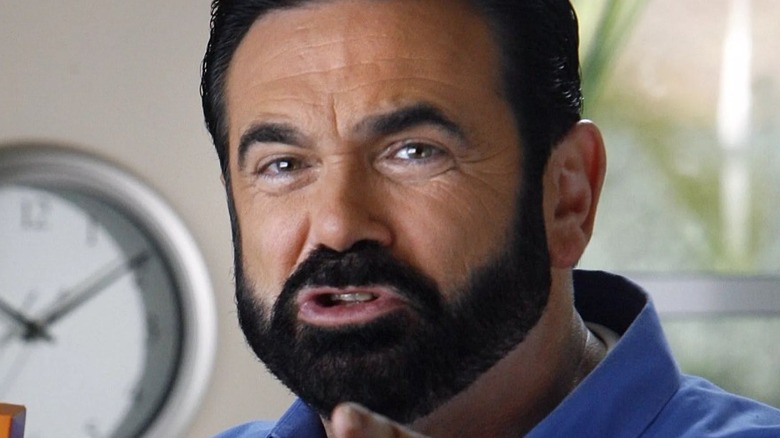

Disturbing Details Found In Billy Mays' Autopsy Report

The Truth About Joel Osteen And Kanye West's Friendship

William Shakespeare Probably Wore This Piece Of Jewelry

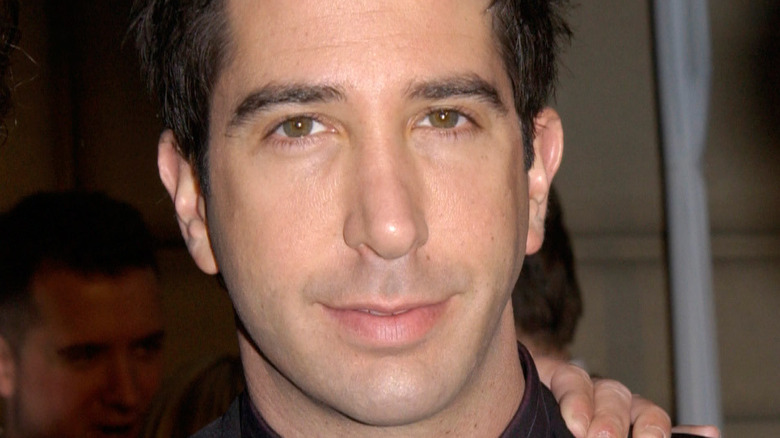

Tragic Things That Happened To The Cast Of Friends

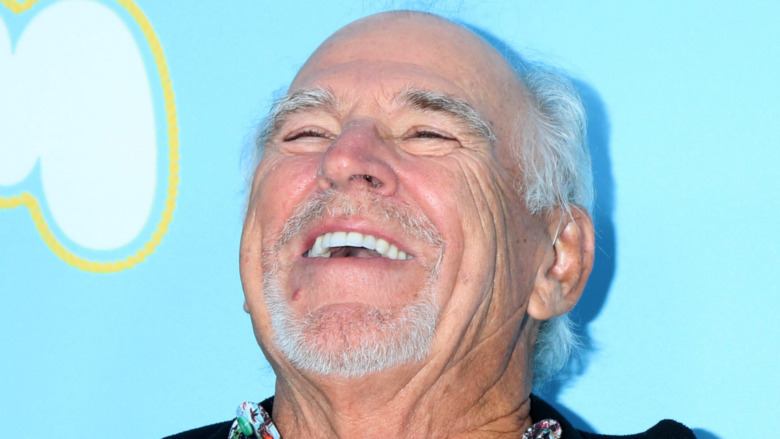

The Truth About The Musician Who's Released Around 400 Albums

What The Final 12 Months Of Cass Elliot's Life Looked Like

What Fans Don't Know About Action Bronson

Matthew McConaughey's Doritos 3D Commercial Is Turning Heads

The True Story Behind Motley Crue's Without You