The Best Westerns Starring Clint Eastwood

In his tenth decade, Clint Eastwood remains an American icon. He’s shifted and changed his roles and his approach as time passes, effortlessly remaining at the top of the Hollywood game. Over the course of Eastwood’s epic career, he’s played radio disc jockeys, police detectives with anger issues, Secret Service agents, boxing trainers, and bare-knuckle brawlers.

But the roles that have truly defined Eastwood are his Westerns. From bit parts on TV in the 1950s to a starring role in “Rawhide” in 1959, through his “Spaghetti Westerns” with the legendary Sergio Leone to his own films in the last few decades, few actors of his generation are as identified with the genre. In these films Eastwood perfected his stoic, laconic anti-hero persona. Embodying a uniquely American attitude and visual sense, Eastwood’s craggy face and raspy drawl have come to define an old-school masculinity that allows for humor, weakness, and emotional depth without sacrificing the sense that even at 90+ years old, Clint Eastwood could kick your butt and not break a sweat doing it.

If you need a reminder of what makes Clint Eastwood one of the greatest actors of all time, here are the best westerns starring Clint Eastwood—in reverse order of perfection.

He was sexy as heck in The Beguiled

“The Beguiled” is often overlooked because it’s not a typical Western. But this story of a Union soldier during the Civil War who is brought to an all-female seminary to recover from his wounds accomplishes something that needed to happen in 1971: It reminded the world Clint Eastwood is a damn fine good-looking man.

As Rolling Stone points out, though, what makes this movie truly special is it subverts Eastwood’s immense charisma and turns it against his character. After almost two decades playing squinting, intimidating tough guys with a six-shooter on their hip, Eastwood plays a man terrified of returning to the battlefield, and who initially uses the women’s attraction to him to his advantage. He thinks he’s in control of the situation. But unlike other Eastwood roles, he’s actually the weak link in the situation. He’s at the mercy of these women, and when he takes his manipulations too far things go very badly for him.

As That Moment In notes, the film was released at the height of what is sometimes referred to as The Sexual Revolution, a moment in history where women were pushing for more autonomy over their bodies and their love lives. Having Clint Eastwood play a sex object who is ultimately powerless against a group of women was a powerful statement—and one that still holds up, in large part because of Eastwood’s fearless performance.

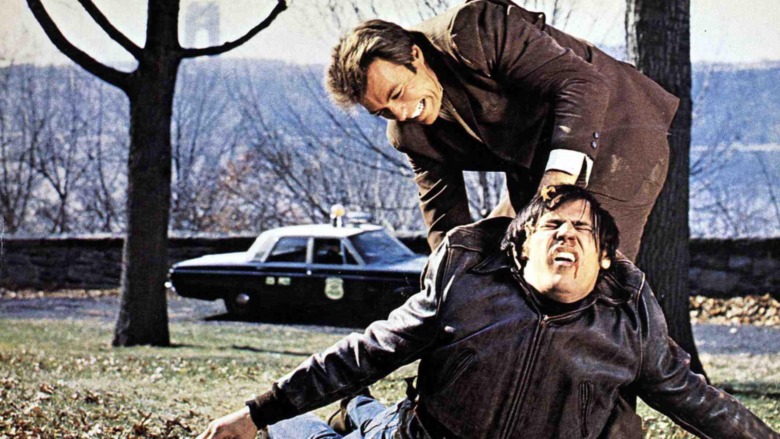

A classic Western update: Coogan's Bluff

The Western genre isn’t necessarily tied to a specific time or place. “Coogan’s Bluff,” set in contemporary 1968 America, is just as much a Western as any movie involving gunslingers in the Old West.

Eastwood plays Arizona deputy sheriff Walt Coogan, sent to New York City to bring back murderer James Ringerman. Coogan is horrified and disgusted by New York, and quickly runs afoul of both criminals and the local police, who distrust his rough, out-of-town approach to law enforcement. As Roger Ebert noted in his review, the film trades in classic Western tropes—the one incorruptible lawman, the moral and ethical purity of Western folks versus the scheming, untrustworthy city people, and the power of a tough, unbending lawman.

Equally important, as Rolling Stone notes, is the way the film helps transition Eastwood from his cowboy roles into a more mature screen persona. It’s safe to say he wouldn’t have been “Dirty Harry” if not for “Coogan’s Bluff,” which updated his persona and proved it could work in a modern setting. The film also paired him with director Don Siegel for the first time, a collaboration that would yield some of Eastwood’s best work. And Siegel takes what could have been a dull montage of fight scenes and turns it into a terrific thriller that stands the test of time despite some wonky anti-hippie politics.

The criminally underrated Two Mules for Sister Sara

Probably the most overlooked film in Clint Eastwood’s career, “Two Mules for Sister Sara” is often unfairly categorized as a minor comedic experiment for Eastwood, but the film is much smarter and innovative than it initially appears (a misapprehension caused in no small part by its absolutely terrible, no-good title).

As noted by Roger Ebert, Eastwood plays a variation of the “man without a name” role he’d already perfected, a man named Hogan. The performance plays with that established persona, as well as tried-and-true Western tropes regarding fallen women and stoic heroes. Hogan rescues Sara from a sexual assault in the wilderness of Mexico, discovers she appears to be a nun, and chivalrously agrees to platonically accompany her on a mysterious mission. The sexual tension is thick from the get go, and as The New York Times notes, the film operates on several levels at once. It’s very funny—Eastwood’s silent reactions are absolutely side-splitting—but it’s also romantic as the two characters work very, very hard to ignore the fact they look like Shirley MacLaine and Clint Eastwood.

Directed by Don Siegel, the film is also a satisfying and well-staged action thriller that leads to a literally explosive ending after a series of complex twists and turns involving Sara’s true identity and her purpose in the backwoods of Mexico. The film holds its own against any of Eastwood’s other Westerns.

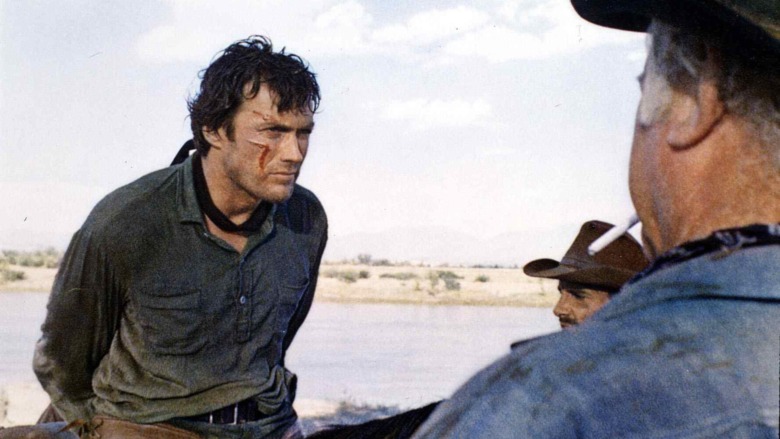

The surprisingly complex Joe Kidd

Any Western with a script by the legendary Elmore Leonard is worth seeing, and Eastwood’s blazing performance as a drunken, burned-out bounty hunter seeking revenge against a wealthy landowner who betrayed him elevates this film even further. As Mostly Westerns points out, “Joe Kidd” is the film where Eastwood found the perfect balance between the more expressive acting he’d experimented with in the 1960s and the more laconic, physical acting he’s really known for. His low-key, naturalistic performance serves the story well, and his role as Kidd could be retroactively viewed as a younger version of the washed-up gunslinger he’d play two decades later in “Unforgiven.”

As the AV Club points out, one of the best things about “Joe Kidd” is the fact the director knows what he has with Eastwood’s face, and uses close-ups to powerful effect. Kidd is a broken man with a fierce sense of justice, and that streak of heroism is slowly revealed as the hard outer shell of pain and rage is rubbed away by the violent events of a manhunt gone wrong. As such, it’s a role genetically designed for Eastwood, who is revealed here as the absolute king of the slow burn. His artful performance as Kidd gradually boils from passively angry to explosively violent, even if the plot sometimes wanders a bit away from logical sense. All in all, a severely underrated film.

Hang 'em High had the moral high ground

After Eastwood’s breakout success in Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns “A Fistful of Dollars,” “For a Few Dollars More,” and “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly,” someone was bound to wonder if you could recapture that magic in an American-made movie. The result was 1968’s terrific “Hang ‘Em High.”

As noted by Roger Ebert’s review, this is a revenge story. Eastwood plays Marshal Jed Cooper, who is mistaken for a cattle thief and hung by a posse of men without even a hint of due process or even curiosity as to his explanation. When Cooper is rescued and eventually named a Federal Marshal, he embarks on a grim tour of a bleak, violent Old West to track down and punish the men who tried to kill him.

As noted by Great Western Movies, while the movie is bleak and revels in the sort of steely-eyed violence Eastwood is very good at, it also has something subtly profound to say. There’s a surprisingly nuanced exploration of capital punishment and the real meaning of justice in the story, giving it a depth most Westerns lack. Cooper is a man who survives a wrongful hanging—but his storm of vengeance results in other wrongful hangings, perpetuating a cycle of violence that solves nothing. It’s a gripping performance in a story that’s almost biblical, and Eastwood’s performance showed he was ready for more complex roles.

Pale Rider's straightforward power

Clint Eastwood has spent his career relentlessly subverting, interrogating, and flipping tropes and clichés—especially in his Westerns. This is the man who portrayed “Dirty” Harry Callahan not so much as a hero cop battling evil but as a dangerous sociopath who considers rules to be for other people, after all.

But “Pale Rider” achieves greatness by being the opposite — it’s a clean, straightforward Western that simply tells a grand, extremely American tale of individualism versus corporate interests. As Roger Ebert notes in his review, by 1985 Eastwood was supremely confident in his acting style and range, and directs himself perfectly, allowing silence and facial expression to do more work than dialog or action. Eastwood plays Preacher, an avenging angel of violence who may or may not be a supernatural force of justice, and films himself like Death riding in—in other words, epic in every sense.

Arriving mysteriously to defend a struggling town on the verge of destruction due to the greed and callous disregard of a mining tycoon, Preacher may or may not be a ghost or a supernatural force, but he’s extremely skilled at violence. As Thrillist notes, he uses that skill exclusively in the defense of the innocent against the evil—there’s no subtext, no subtle twist. There’s just clean, affecting visuals, a well-told story, and an actor/director leaning into what he does best.

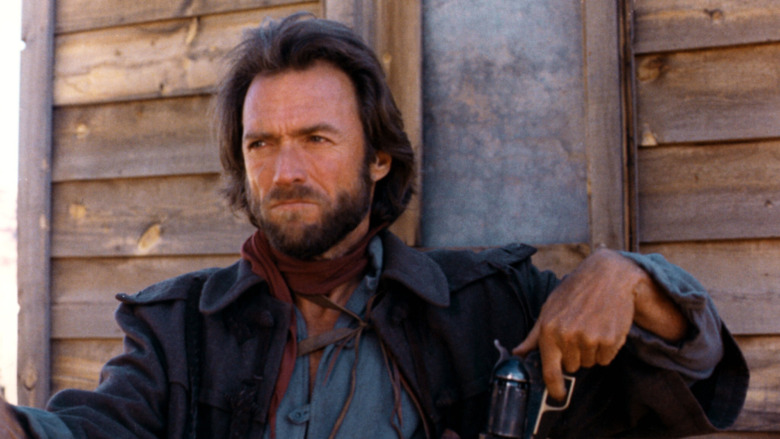

Playing against type in The Outlaw Josey Wales

The evolution of Clint Eastwood’s onscreen persona in the Western genre is a steady move away from death dealers who rarely seemed to feel anything. By the mid-1970s, Eastwood was exploring a richer emotional palette, and this willingness to push his own performance resulted in one of his best movies: “The Outlaw Josey Wales.”

An operatic revenge story about a normal guy whose family is murdered by one of the many unofficial militias employed by both sides in the Civil War, this is a film genetically engineered for Eastwood. As Mostly Westerns points out, Wales starts off as a character against Eastwood’s type: He’s a farmer, not a fighter, and he’s warm, emotional, and a loving family man. The film then thoughtfully tracks his transformation into a rage-fueled killing machine, almost as if offering an explanation as to how a man becomes Clint Eastwood in “The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.”

It’s easily one of the most underrated Westerns in general—Rolling Stone calls it “one of the finest horse operas of the 1970s, period”—and Eastwood is so in the zone as the title character his performance could be mistaken for lazy—but it’s very precise in its details. Eastwood’s transformation from a loving, emotional family man into a snarling dealer of death is remarkable.

The most underrated Western of all time: High Plains Drifter

One thing that links almost all of Clint Eastwood’s characters is catharsis. Many of his roles are revenge tales involving bad guys getting what they deserve, allowing audiences to root for Eastwood’s stoic gunslinger to set things right. What’s fascinating about “High Plains Drifter” is Eastwood purposefully weaponizes that expectation against the audience.

Anyone who has ever craved the ability to punish those who have wronged us thrills to The Stranger in “High Plains Drifter,” a man hired by a desperate town to defend it against a gang of outlaws. But The Stranger has his own motivations, and the story delves into the nature of justice and punishment. As Esquire points out, it’s almost an experimental film, filled with lush psychedelic flashback sequences and toying with the nature of reality—specifically, is The Stranger really there, and is the town a real place, or is everyone in a hell of their own making?

As Rolling Stone notes, Eastwood’s direction is terrific—it’s only his second film behind the camera and he already knows less is more. At the same time, he unleashes some truly horrific violence, but it’s violence with a purpose, intended to underscore that the world is what we make of it. If we allow injustice and evil to fester, violence is what we get. It’s a spare, tight masterpiece.

A sequel as good as the original: For a Few Dollars More

Sergio Leone’s “A Fistful of Dollars” was a revelation in 1964, a sudden leap forward for the Western genre. “For a few Dollars More” is the rare sequel that is almost as good. As PopMatters notes, it succeeds in part because it’s not so much a sequel as a reinvention—Leone tells a wholly new story, and it’s an open question whether Eastwood’s Man with No Name is supposed to literally be the same person or literally a trope come to life. The freedom of simply wiping the slate clean allowed Leone to take everything that worked in the first film and discard anything that didn’t. “For a Few Dollars More” is overlooked because it wasn’t as revelatory as the first film in the trilogy, and it wasn’t as perfect as the final film (“The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly“), but it’s one of the best Westerns Eastwood made—and one of the best of all time.

Middle stories in trilogies are often more subdued and complex, and that’s the case here. As Vulture notes, the story of two bounty hunters who carefully combine efforts to bring in a dangerous outlaw brought an emotional aspect to Eastwood’s Man with No Name that resonates. There’s a world weariness to the story here that undercuts the incredible violence and makes it feel tragic.

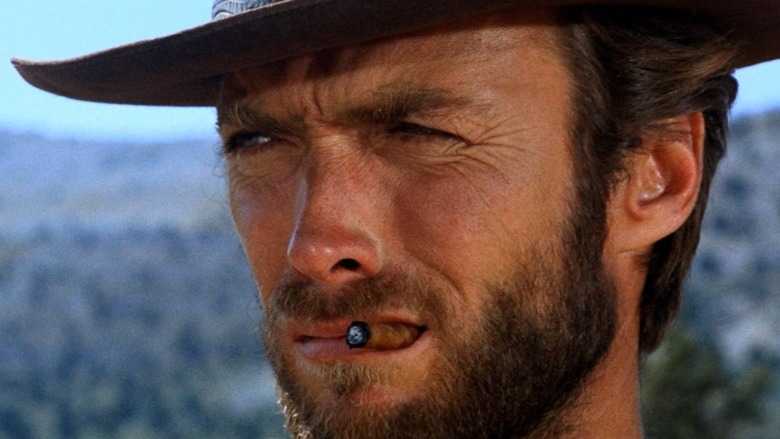

The Spaghetti Western that changed everything: A Fistful of Dollars

The first film in Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Western trilogy, “A Fistful of Dollars” had an enormous impact on the genre, somehow combining realism—the dirt and sweat of unwashed criminals in the Old West is so palpable on screen you can almost smell the characters—with an operatic style. It established Eastwood as a major star and changed the stories Westerns were telling, and how they were told. It’s hard to overstate how influential this film is—and as Rolling Stone notes, it’s the film that established what we think of today as Clint Eastwood’s onscreen persona.

It also didn’t look or feel like any Western before it, and it changed the rules concerning the stories a Western could tell—and what kind of protagonists they could explore. As Vulture explains, Eastwood’s Man with No Name is cheerfully amoral. He’s not on the side of justice or evil, he’s on his own side until the very end of the film. For a genre like the Western which had always been obsessed with good versus evil, with the necessity of law enforcement to hold back chaos, this was a shocking and exciting departure. This is the first time Eastwood looks and feels like Eastwood in a movie, and it remains a timeless classic of the genre.

Paying off an entire career: Unforgiven

“Unforgiven” is a film you can’t fully enjoy unless you’re familiar with Clint Eastwood’s entire career up to the year 1992. As Rolling Stone notes, the movie turns a critical eye to the “damage done” by the characters Eastwood had portrayed in Westerns in the decades leading up to this Best Picture Oscar-winning triumph, asking both the actor and the audience to consider the horrifying truth of a life defined by murder, revenge, and death. Eastwood’s Bill Munny was once a drunken terror, murdering for money, but when we meet him, he’s an aging widower trying hard to honor the memory of the woman who saved him. When he reluctantly agrees to help an ambitious young gunslinger avenge a prostitute’s slashed face, he finds himself descending back into hell—except this time stone cold sober and aware.

Eastwood’s performance as Bill Munny is an absolute triumph. He’s a man staring down mortality and realizing the kind of damage he could do if he were to ever be freed of ethics, fear, or consequences. As Vulture notes, it’s also Eastwood perfectly distilling his directorial style—if you needed an example of how Eastwood sees cinema, this film is it. With a standout performance by Bill Hackman as the villain, Little Bill, this isn’t just one of the best Westerns ever made, it’s one of the best movies, period.

One of the greatest Westerns ever: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

When it comes to iconic movie Westerns, this is it. Everything about “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly” is iconic, from the theme music—which as Pop Matters reminds us was a dramatic and inspired departure from traditional Western movie scores by the legendary Enrico Morricone—to the freeze-frame introductions to the classic, literal Mexican standoff at the end. Rolling Stone considers it to be one of the greatest Westerns ever made, and it’s hard to argue the point: It takes the revolutionary styling of the previous two films in the trilogy (“A Fistful of Dollars” and “For a Few Dollars More”) and perfects the form, delivering a Western that is epic and myth-like and gritty and realistic to a fault—this may be the sweatiest film ever released.

The story of three very bad men scheming over a stash of gold hidden in a grave remains one of Eastwood’s greatest films—in large part because, as Vulture says, the film is not just an artistic triumph, it’s also “ridiculously entertaining.” Eastwood somehow brings humanity and humor to a mostly silent character, expertly conveying the Man with No Name’s extremely slight lean towards the Good through moments of hesitation and an array of grimaces only a master actor could pull off.

Music Critic Reviews That Aged Poorly

Things You May Not Know About Jackie Chan

The Truth About Paul McCartney's Relationship With Ringo Starr

The Tragic Death Of Billy Preston

Here's What Happened When Someone Tried To Sell New Zealand On eBay

The Worst Member Of Red Hot Chili Peppers Might Surprise You

The Truth About Liza Minnelli's Relationship With Halston

False Things You Believe About Tina Turner

What Did Bob Cratchit Actually Do For Ebenezer Scrooge?

Things Ma Rainey's Black Bottom Didn't Tell You About Ma Rainey