The Messed Up Truth About Opus Dei

It’s possible to write an entire book about why Dan Brown and “The Da Vinci Code” is so polarizing, but for now, let’s talk about a single part: Opus Dei. Brown’s version of Opus Dei features a shadowy organization that employs a murderous monk to do the actual dirty work, and it doesn’t put the group — which is absolutely real — in a good light. There’s no evidence that anything about the monk is true, but if Brown had done a little more digging, he would have found a lot more shady stuff that’s actual fact.

Opus Dei was founded by Josemaria Escriva in Spain in 1928. According to their own history, the spread of the organization was delayed by the World Wars, but as the second edition of those wars drew to an end, Escriva started traveling and taking his organization to other countries. The general idea of the message was getting laypeople into serving God and following Christ with the help of a series of guidelines, and the Roman Catholic Church was fully on board by the late 1940s.

And this is important: Opus Dei is a fully recognized and approved arm of the Catholic Church, so much so that when Escriva died in 1975, it took just six years for calls of sainthood to be answered. Investigations took until 1986, and in 2002, Escriva was made an official saint. That’s pretty much record time, so let’s take a close look at just what the Church is supporting.

What is Opus Dei?

Let’s take a look at exactly what Opus Dei says they are, and what their critics and former members claim they are. Opus Dei says that they’re essentially an organization that provides guidelines on how Christian laypeople can live “a life fully consistent with their faith, in the middle of ordinary circumstances of their lives.” That involves things like “divine filiation,” embracing Christian values like “charity, patience, humility, diligence, integrity, [and] cheerfulness,” prayer, the offering of sacrifices, and “sanctifying work,” which means work that’s done “ethically.”

That sounds not-so-bad, but like anything involving people, it gets very complicated very quickly. Opus Dei has claimed to be different things over the years: NPR says it’s currently defined as a “personal prelature,” but it’s also been called things like a “secular institute” and a “priestly society of common life without vows.” Both laypeople and clergy are members, new members are usually recruited by existing members, and when joining Opus Dei, a contract is signed promising (in part): “with firm resolve I dedicate myself to pursue sanctity and to practice apostolate with all my energy.”

Critics, however, accuse Opus Dei of being everything up to and including a right-wing cult. Take, for example, a joke published in the magazine Tablet: “How many members of Opus Dei does it take to screw in a lightbulb? The answer is, 100… one to screw in the lightbulb, and 99 to chant, ‘We are not a movement, we are not a movement.'”

Former members are incredibly critical

The idea behind the organization doesn’t sound too bad, but according to former members like Tammy DiNicola, there’s a heck of a lot more to it. After Opus Dei appeared in “The Da Vinci Code” and people started looking at just what it was, DiNicola’s own organization, the Opus Dei Awareness Network (ODAN) started getting some attention, too. She says (via ABC) that she got involved with Opus Dei while she was attending Boston College as a freshman, and part of the consequences was a slow breaking of ties with her family and pre-Opus Dei friends.

DiNicola also talked about how once she moved into an all-female residence overseen by the organization, she found her mail was read by her superiors first, her paycheck went to the group, and if she needed to go shopping, she was only allowed to with permission from Opus Dei leadership, who oversaw most of what she did.

According to the BBC, there are three different groups within Opus Dei. The supernumeraries are the married members who lead everyday sorts of lives, and that’s somewhere around 75% of the organization. The rest are associates and numeraries, and these are the celibate members who some claim play a different role. Dennis Dubro was in that 25%, inner circle, when he left after 17 years. He later said, “I was in levels of leadership and like an onion, the outer core never finds out about these things.”

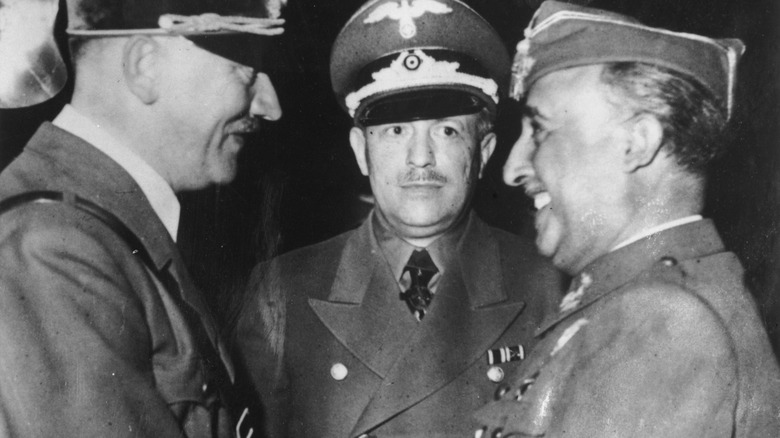

Opus Dei's connections to Spain's Francisco Franco

First, just a quick history refresher. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War came to an end and Francisco Franco took charge. For an idea of what kind of ruler he was, he had friends in both fascist Italy and Nazi Germany (that’s a picture of him meeting Hitler). He had at least 26,000 of his critics jailed as political prisoners, banned languages like Basque and Catalan, and established a massive spy network tasked with keeping an eye on Spain’s own citizens (via History). In short, he really wasn’t a nice guy, but according to NPR, a huge source of the controversy involving the early days of Opus Dei involves the fact that the organization’s founder, Josemaria Escriva, was a big Franco supporter.

The Guardian describes Opus Dei as “ultra-conservative,” and as such, their ideas were on the same side of the political spectrum as Franco’s. Even as Franco outlawed all religions except for Catholicism — and went as far as forbidding ethic groups like the Basque from giving their children traditionally Basque names — Escriva recruited some of the earliest, most powerful members of Opus Dei from Franco’s wealthy elite. Some of the members also held prominent positions in Franco’s government, including Minister of Finance Navarro Rubio, Minister of Industry Lopez Bravo, and Minister of Commerce Alberto Ullastres Calvo (via JSTOR).

Meanwhile, Opus Dei thrived under the umbrella of Franco’s dictatorship.

Spain's stolen babies

Ines Madrigal was born in 1969, and she doesn’t know what happened to her mother. She does think she knows why: just after she was born, she was taken away by her mother’s gynecologist and given to a wealthy couple who couldn’t have a baby of their own. That was denied by the gynecologist in question, but according to Federico Lopez-Terra, Swansea University Lecturer in Hispanic Studies (via The Conversation), she’s not alone in her convictions. It’s estimated that somewhere around 300,000 babies were removed from their biological parents and given to others, starting in 1939 during Franco’s rule, and continuing until the 1990s.

The basis goes back to Antonio Vallejo-Nagera, a man tellingly called “the Spanish Mengele.” He was in charge of “psychological research” under Franco, and promoted the idea that anyone who didn’t agree with Franco’s policies was mentally and physically inferior, and yes, that’s diving straight into the “Nazis and fans of eugenics only” end of the pool.

That’s horrible, but where does Opus Dei come in? According to El Pais — who adds that many of the biological mothers were told their baby had died — the organization behind the vast network of hospitals and children’s homes involved many members of Opus Dei. Researcher and sociologist Francisco Gonzalez de Teana says they were the doctors who took babies and signed paperwork, they were the judges who facilitated adoptions, and they were the clergy who saw the stolen babies placed with new families or in institutions until adulthood.

Giving up their oldest son

UCLA professor and neuroscientist Hermes Solenzol has written (via Medium) extensively on what it was like growing up in a Franco-controlled Spain and in an Opus Dei family. He was enrolled in a “children’s club” overseen by the organization when he was seven years old, and it wasn’t his first experience with Opus Dei. His father was a supernumerary — part of the 75% — while his uncle was a numerary, part of the 25% that swore to a life of poverty and chastity.

He described his education: “They had to offer in sacrifice their eldest son, which in this case would be me. I am only half-joking. What really happens is that they are asked to put their children in clubs… where they are carefully groomed and indoctrinated. Then, when they turn 14, they would be asked to join Opus Dei.”

Solenzol says that his daily education was interspersed with “meditation,” where he and other students would read from Josemaria Escriva’s book “Camino (The Way),” in which they would learn about the “999 points” that guided life within Opus Dei. That included something called “saintly coercion,” which is described as “using force … to save the Life of those who idiotically persist in committing suicide of the soul.” That’s heavy stuff for an adult, much less a child, and according to Elena Moya, some of the Opus Dei members she knew pledged themselves to a life of celibacy at just 13 years old (via The Guardian).

Issues around their Opus Dei-run schools

In 2012, Opus Dei announced two new schools were going to be opening in London. The Cedars — a boys-only school — and the Laurels — the girls-only version — were being set up by an Opus Dei-based charity called Parents, Children, Teachers Educational Trust, would be “inspired by the philosophy of St. Josemaria Escriva,” and staffed by Opus Dei members. Opus Dei schools aren’t that strange, but some of the countries they’re in have had some serious issues with them.

Let’s take Ireland for starters. In 2015, the Irish Independent reported that the Opus Dei-inspired Rosemont School had — in spite of submitting documentation saying they were abiding by educational guidelines that said all students must receive education on relationships and sexuality (RSE), parents and students both said that was sorely lacking. Then, in 2020, there was outrage when schools — including Opus Dei’s private Rockbrook Park School — invited “American Catholic chastity campaigner” to share his controversial views with students. That included beliefs that birth control and LBGTQ+ orientations are “disordered.” The speaking engagements were ultimately cancelled (via RTE).

Opus Dei has had even less luck in Germany. In 2007, DW reported that the State Education Ministry refused to even allow an all-boys, Opus Dei-backed school to open in Potsdam, citing the fact that an all-boys school violated laws that gave all children the right to an education regardless of gender.

Some use desire-supressing devices

“The Da Vinci Code” included depictions of some rather gruesome corporal mortification, but how accurate was it? Opus Dei defines the practice as “join[ing]” [Christ] in his redemptive suffering,” and says that common types of voluntary suffering are things like not eating meat on certain days, and giving up something for Lent. They say that the organization “gives more emphasis to everyday sacrifices,” but they also add that Christian theology says mortification is a necessary part of resisting evil and saving the soul.

Elena Moya graduated from one of Opus Dei’s universities, and says there’s much more to it. She wrote (via The Guardian) that she knew multiple people who wore something called a celice (or cilice) –like the one pictured — “in order to suppress desire.” She was a college student at the time, and college students are basically walking, talking hormones. So what, exactly, is a celice?

It’s basically a metal ring with spikes, that Moya said was typically worn around a person’s thigh. She said she knew people who would wear it so tightly that it would cause bloody wounds, and yes, Opus Dei says that some members definitely use the device. Their version of the story is a little different, and they say there’s no bloody wounds involved. Instead of “spikes,” they say the ring has “prongs,” and that it’s simply meant to be uncomfortable, not painful to the extent where it causes lasting harm. Any suggestion otherwise, they say, is “so nutty.”

One of their ranks forgave an FBI agent… who was also a Soviet spy

The story of Robert Hanssen is a decades-long tale that’s worthy of a Netflix series, but here’s the basics. In 2001, he was arrested by the FBI — which he had been an employee of since 1976 — for being a Soviet spy. Instead of denying it, Timeline says he asked, “What took you so long?” Hanssen’s wife, Bonnie, took a polygraph test not long after, and according to The New York Times, she said that she had known he had dealings with Russia, and believed him when he told her that he was giving them false information as a part of his job with counterintelligence. He was not, and here’s where Opus Dei comes in.

The Hanssens were a part of Opus Dei, and Bonnie insisted that Robert confess to an Opus Dei priest named Rev. Robert P. Bucciarelli. Bucciarelli promised he could get Hanssen out of that whole pesky prison thing, because if he donated what money the Soviets had given him — and promised to stop spying — then the priest would give him permission not to report himself to the FBI.

Robert had already spent somewhere around $30,000 of Soviet cash, and convinced his wife that he was in the process of paying his debt to charity — as Opus Dei requested. It would be another 20 years before Hanssen would be put under full-time FBI surveillance and then arrested. He ultimately made a plea deal for life in prison instead of the death penalty.

Paying to settle sexual assault lawsuits

In 2015, The New York Times did a piece on Rev. C. John McCloskey III, who they called the “Opus Dei Priest With a Magnetic Touch.” It was perhaps a poor choice of words. McCloskey, they wrote, joined Opus Dei after going to college, and was posted to a Washington, DC outreach ministry called the Catholic Information Center. It was there that he discovered he had a knack for converting the rich and powerful to the ways of Catholicism and Opus Dei, and the piece was basically an interview with everyone except McCloskey: Opus Dei forbade him from officially speaking on the record.

It wasn’t until four years later that The Washington Post reported on something of a bombshell: in 2005, Opus Dei had paid out a whopping $977,000 to settle a lawsuit in which a woman accused McCloskey of groping her during sessions where she consulted him for advice in matters of mental and marital health. Following the incident, he reportedly absolved her of her guilt, but she soon spiraled deeper into the depression she already struggled with.

That, says the report, is when Opus Dei stepped in, paid her nearly $1 million, and initially covered up the incident. It was only later that they made a statement that included an apology: “We are very sorry for all she suffered.” McCloskey was removed from the location of the complaints and sent elsewhere to continue his work for the church and Opus Dei.

The conspiracy theory around a Swiss Guard's murder

First, the official version of the story, via SwissInfo. Alois Estermann was promoted to the commander of the Vatican’s Swiss Guard in 1998, and within hours, he and his wife were dead. They were killed by another member of the Swiss Guard, Cedric Tornay. After killing them, he then killed himself. The motive was claimed to be anger that he had been overlooked for promotion.

That may have been the official story, but there were a ton of theories on what really happened. Then, in 1999, a few anonymous authors published a book on one of those theories, which basically said that Estermann had been a casualty of a power struggle within the Vatican. According to The Guardian, the book claimed that the two opposing factors were the ultra-conservative Opus Dei and a “masonic power faction,” and that Tornay not only hadn’t pulled any triggers, but that he’d been executed to make the whole thing look like a murder-suicide.

The book, “Blood Lies in the Vatican,” also alleges that Estermann was one of Opus Dei’s money guys, and that the all-too-brief investigation into what happened was, well, all too brief. Tornay’s mother wrote a blurb for the book, expressing her belief that “this is the origin of the great effort made by the heads of the Roman Curia to prevent a terrible truth being revealed to the world.”

Their views on 'true feminism'

Opus Dei has addressed their views on women and accusations that they’re “unenlightened.” They say it’s just not true, and that the organization believes in seeing women dedicate themselves to a holy life that can come with a variety of occupations and callings.

In 2009, some of the women involved in Opus Dei contributed to a book aptly titled “Women of Opus Dei: In Their Own Words.” In it, some talk about “true feminism,” which doesn’t exactly come off as well as Opus Dei might have intended. Take the comments of Claire Huang, who says, “True feminism recognizes that women bring different qualities to the workplace than men. Women can have a nurturing attitude and do things at work that are caring… Women add warmth; that’s why motherhood is such a beautiful thing.”

Religion Dispatches makes some interesting observations: The women in the book either have jobs or children, but not both. The so-called “true feminism” of Opus Dei echoes Catholic ideas about why women aren’t suited for leadership, and motherhood. Also: Motherhood. Oh, and being a mother. Having children? That’s also super important. Another contributor lauds motherhood as a true calling in which women are “sharing in God’s work of creation,” and it all leaves the critic to come to the conclusion that although it’s all meant to further the idea that Opus Dei is all about equality, it doesn’t read like that at all.

Assistant, or slave?

When Shon Faye spent a year living in a residential hall run by Opus Dei, they later wrote (via Vice) that the only women allowed in the building were the numerary assistants, who cleaned while everyone else was locked out for a few hours.

The National Catholic Reporter says that until 1982, these Opus Dei members were originally called “servants,” and the 4,000-odd women were instructed “to work in a spirit of ‘full submission'” according to the official Opus Dei documents that they signed. Most are recruited in high school, and sent to “‘hospitality’ training centers,” where they’re taught how to do things like cleaning, laundry, and cooking… the Opus Dei way.

In 2011, one of these numerary assistants took Opus Dei to court. The Telegraph reported that Catherine Tissier filed a lawsuit claiming that she was forced to work seven days a week, beginning at 7am and ending at 10pm, wasn’t allowed to speak to her family, was given antipsychotic drugs when she complained of suffering from depression, and was forced to sign all her wages over to her employers. Tissier says that her parents intervened and “rescued her” after 15 years, and four others came forward with similar claims. Just a few weeks later, The San Diego Union-Tribune reported that the French court had acquitted the accused members of Opus Dei.

Accusations of forceful recruitment

Elena Moya says that her university — the University of Navarre — happened to be owned by Opus Dei, so she saw a lot of people who were chasing membership. Moya says (via The Guardian) that prospective members had to be 18 to make their pledges, but adds that she knew some as young as 13 who vowed to lead a life of chastity.

And that leads into some incredibly serious accusations over recruitment policies. In 2006, ABC News spoke to Tammy DiNicola, who has been incredibly vocal about what she calls aggressive recruitment policies that are directed at teen- and college-age students. DiNicola says she was targeted, and before she knew it, she was living in a controlled environment where everything was restricted. Her mother explained: “You couldn’t reason with her. … She was not making free choices.”

She says that she was told leaving Opus Dei was an automatic damnation to hell, and UCLA professor, neuroscientist, and son of Opus Dei parents Hermes Solenzol offers some insight (via Medium). He says he was “groomed” by Opus Dei starting when he was seven years old, and it was only when he was old enough to choose a non-Opus Dei priest as a confessor that he was encouraged to explore other teachings. This priest, he says, “pointed out a few things I should watch out for, like the way they used jobs and other perks to manipulate people.”

Opus Dei priests found guilty of sexual abuse

Not all priests are members of Opus Dei, but according to Crux, those that are, aren’t exempt from prosecution for sexual abuse.

In 2020, the organization announced that one of their priests — 72-year-old Father Manuel Cocina — had the not-so-honorable distinction of being the first Opus Dei priest to be sanctioned by the Vatican after sexual abuse charges were filed. His victim was also a member of Opus Dei, and after filing charges, several others came forward with similar allegations. The priest was given “five years of suspended ministry,” and was still permitted to perform private Mass.

Another Opus Dei priest, Father Michael Barrett, was charged (alongside a former cardinal named Theodore McCarrick) in 2021. The Catholic News Agency reported that the charges were filed under the Child Victims Act, by an individual who accused Barrett of first inviting them to an Opus Dei house, where they were subjected to “criminal sexual assault” repeatedly, when the victim was between the ages of 13 and 16. Opus Dei declined to comment.

Shh: Don't say you're a member. Is Opus Dei a cult?

In 2016, Vice ran a piece by a then 27-year-old who had spent 2010 living in an Opus Dei-run residential hall. They were looking for a place to stay in North London during the college term, and the first hint that something was up was an explanation from the house director: He’d been a lawyer before he “was asked to come and work here.”

That’s not entirely surprising, as secrecy about involvement in Opus Dei is pretty common. Elena Moya — who graduated from Spain’s University of Navarre, which is owned by Opus Dei — agrees (via The Guardian). The BBC adds there are no official lists of Opus Dei members because of their belief that being a part of the organization should be private, and that’s helped give rise to accusations that Opus Dei can be defined as a cult. Esquire said as much, when reporting on Opus Dei’s $1 million payout to settle a sexual assault lawsuit.

When Mumbai’s Opus Dei director Mariano Iturbe spoke to The Economic Times, he took the opportunity to clarify that no, they were not a cult — and Dan Brown’s depiction of them had little to do with reality. Still, John Roche — a fellow at Oxford’s Linacre College — pulled no punches when he described Opus Dei (via the Financial Times) as “an Orwellian world employing much doublethink, and internal and external deception.” He also called it “virtually a cult or sect in spirit, a law unto itself.”

The Adam And Eve Theory That Caused A Stir

The History Of Archangels Explained

Cocaine Cowboys: The Tragic Death Of Augusto Falcon's Wife

The Truth About Dan And Betty Broderick's Children

Why George Washington Never Had Kids Of His Own

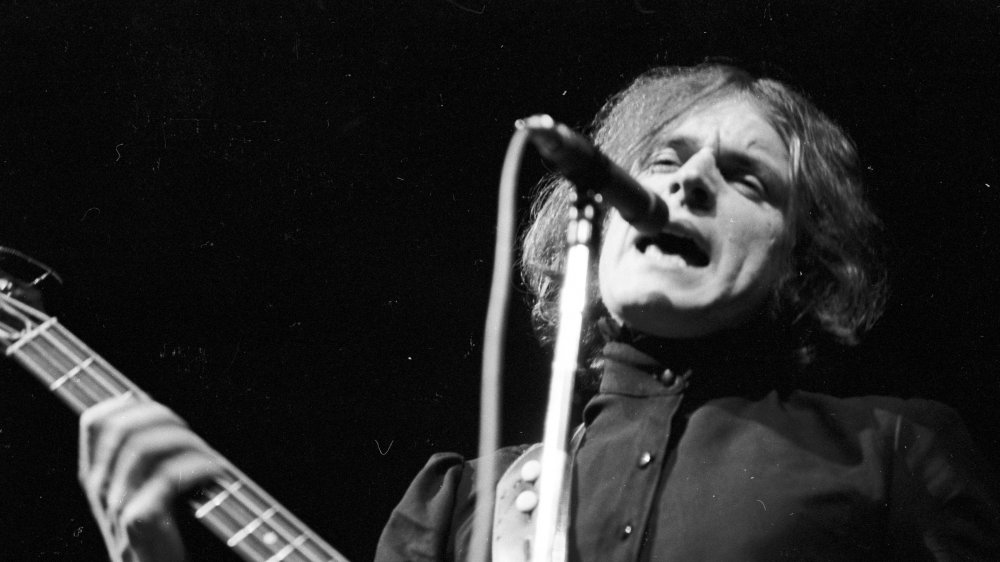

The Tragic Death Of Paul Butterfield

The Tragic Murder Of Manuel Buendia

A Look At Dorothea Puente's Relationship With Everson Gillmouth

Robert Wilson: The Truth About The Man Suspected Of Killing The Boston Strangler

Who Won The Falklands War And Why Did It Happen?