The Untold Truth Of Edward Gorey

Edward Gorey’s art is unique, and no other artist has come close to replicating the style and atmosphere of his intricate ink drawings. The ominous, vaguely Victorian settings and the spindly and disturbingly calm human figures, which are elongated, with round heads and tiny black pools for eyes, are instantly recognizable. Two decades after his death, Gorey remains an almost subliminal presence. Everyone recognizes his work, even if they may not be able to recall his name.

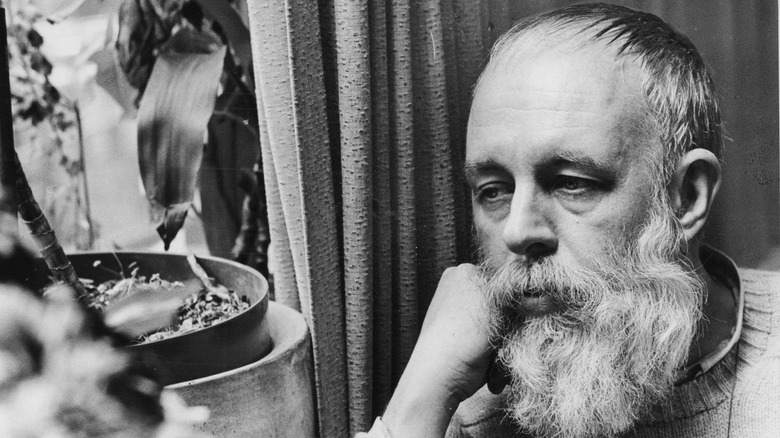

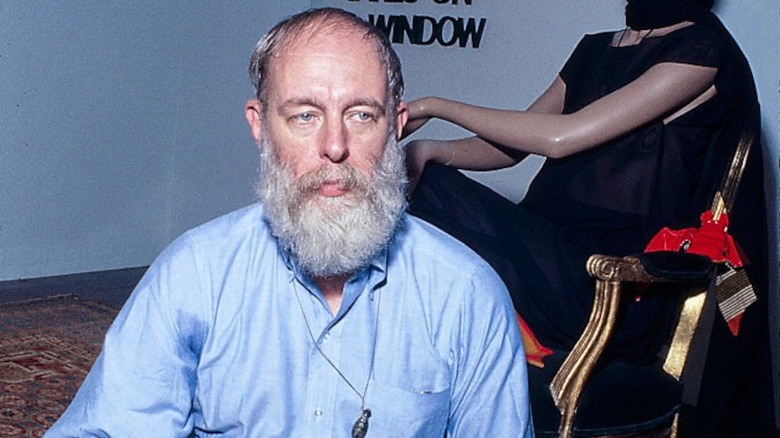

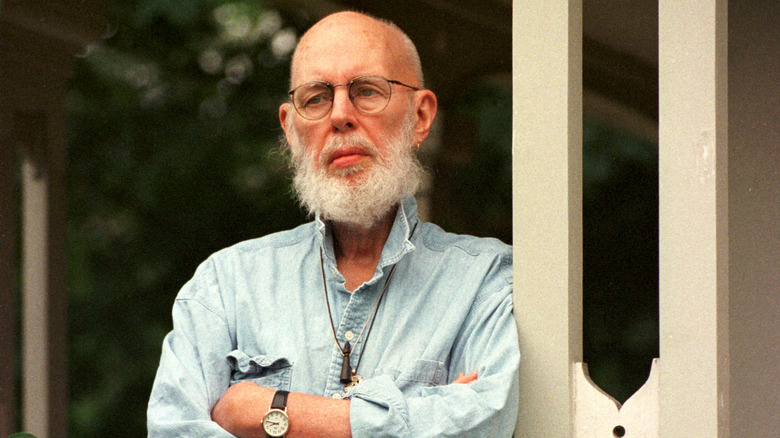

Gorey’s life and personality remain remarkably obscure. He was born in an era of declining privacy and exploding media presence, yet managed to maintain a surprising degree of privacy. This is even more remarkable when you consider the eccentric and often performative nature of Gorey’s daily life. He favored big, extravagant coats, scarves, and plenty of jewelry, was obsessive with the ballet, and regularly staged intricate hand puppet shows. But somehow, Gorey remains mysterious to most people beyond his most famous works.

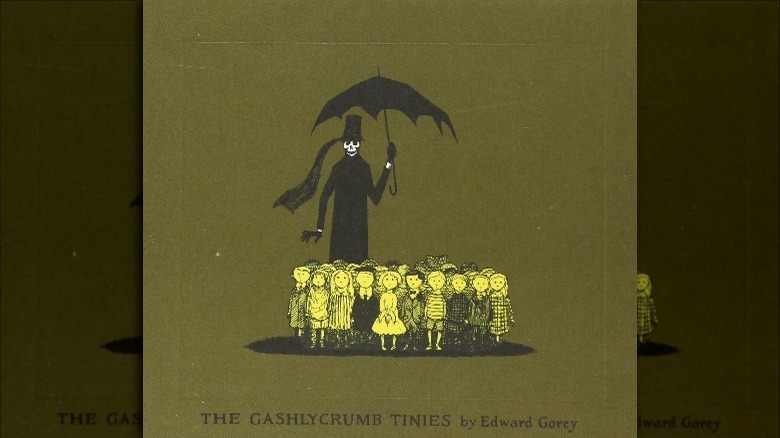

As you might imagine, the man who created “The Gashlycrumb Tinies” and “The Doubtful Guest” lived a fascinating life, one that he lived by his own terms. Gorey refused to bow to convention or expectation, and left behind a legacy of both fierce creativity and remarkable self-knowledge. This is the untold truth of Edward Gorey.

Edward Gorey was a gifted child

Gorey was born in Chicago in 1925. Acording to the Lineup, Gorey was drawing by the age of 2 and had taught himself to read by 3. He was clearly an extremely bright child, but by most accounts he had a relatively normal childhood. He attended public schools in Illinois, where one of his classmates was the actor Charlton Heston. Sadly, his parents divorced when he was just 11 years old (and then remarried 16 years later). Gorey once remarked that didn’t think he even noticed his parents had split, and his childhood diary doesn’t even mention it, though it is filled with ruminations about cats.

By the time he graduated from high school, he had multiple scholarship offers from prestigious schools, but was drafted into the army in the midst of World War II. After his service, he opted to attend Harvard, where he became known as a dandy for his eccentric fashion. According to Harvard Magazine, he “arrived sporting a full-length sheepskin-lined coat, sneakers, and thick rings on his long fingers. His hair was combed forward, Roman style. A typical freshman he was not.” He roomed with the poet Frank O’Hara, and the two became great friends.

Edward Gorey had almost no formal art training

Edward Gorey’s illustration style is deceptive. As Lines and Colors notes, it is deliberately retro, evoking a vaguely Victorian or Edwardian setting with details culled from a broader range of history. It alternates between spare and stark and wildly detailed, reminding some of engravings. RetroFuturista explains that Gorey’s unique black-and-white style deliberately evokes traditional illustrations in children’s books without the usual “sunny” and “colorful” style, which he said he found “boring boring boring.”

Gorey’s style is unique, recognizable, and influential, but he had almost no formal art training. The Christian Science Monitor reports that he attended a single semester at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and was otherwise totally self-trained. The lack of formal training didn’t hold Gorey back — he was so obviously talented that he secured work as a book designer and artist with Doubleday Anchor immediately out of college, according to Lit Hub. While working at Doubleday he designed covers for about 50 books, and also created inside illustrations for some. What’s remarkable about the covers is how instantly recognizable they are as Gorey’s work. Even early on, he’d already developed the style that would become his trademark.

Edward Gorey's first book failed

Edward Gorey’s career took off from his time at Doubleday Anchor. Edward Gorey House reports that he found steady work with other publishers until the mid-1960s, when he began working as a full-time freelance artist.

Gorey also had ambitions to publish his own work, but publishers didn’t know what to make of it in the early days. Salon reports that some editors assumed his work was meant to be funny because of its format — rhyming, often silly couplets paired with drawings — and rejected it based on a lack of laughs.

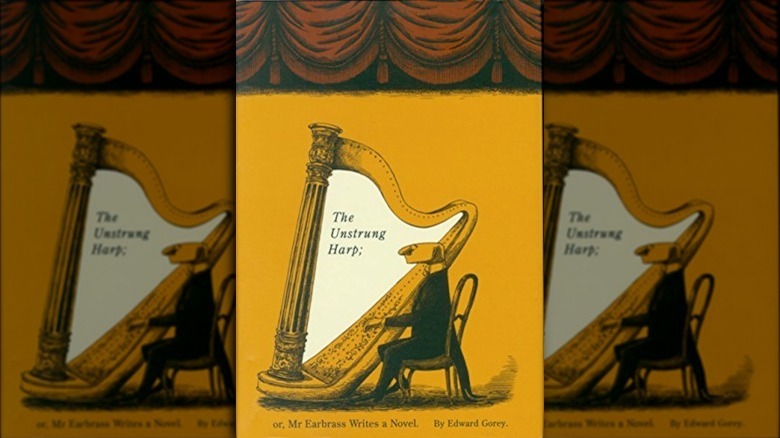

According to the BBC, Gorey published his first book, “The Unstrung Harp,” in 1953. The story of a man struggling to write a novel is pure Gorey, filled with bizarre scenarios and his already-iconic drawings. But the small format of the book and the confusion over its category (since it was clearly not a children’s book, nor was it particularly funny) meant bookstores had no idea what to do with it, and so sales were dismal.

Edward Gorey published under a lot of pseudonyms

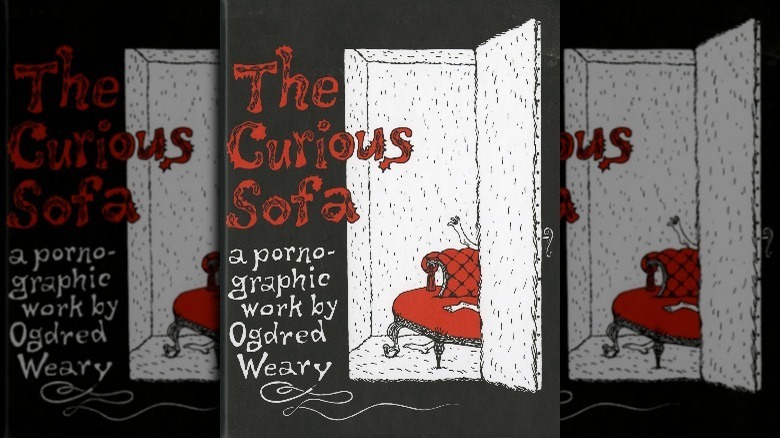

Edward Gorey had a distinctive worldview, and his work is something of an acquired taste. His stories often follow a kind of dream logic, and are populated by strange, ominous people doing strange, ominous things. As a result, he found it challenging to secure book deals — the Toronto Public Library reports that many of his earliest works, like “The Beastly Baby,” confused publishers, who found it too dark. So Gorey founded his own publishing company, Fantod Press, and began putting out his own work, often under playful pseudonyms.

The New Republic reports that Gorey’s love for pseudonyms dates back to his time in the army. While working as a clerk, Gorey wrote several plays under the name Stephen Crest. With Fantod Press, many of his pseudonyms were usually anagrams of his own name, and were almost always female names. The wild monikers he chose include Ogdred Weary, Dogear Wryde, and Ms. Regera Dowdy. He also ventured into complex wordplay with Eduard Blutig, which translates as Edward Gory from German, and O. Müde, German for O. Weary. Brain Pickings reports that some people actually asked the author whether his real name was a pseudonym, as Edward Gorey seems far too perfect for the author of something like “The Gashlycrumb Tinies.”

Edward Gorey won a Tony Award

For all his influence and success, Edward Gorey isn’t exactly a household name. But he had a lot more mainstream exposure and success than you might expect. In fact, many people were exposed to Gorey’s wonderfully weird worldview and artistic sense without even realizing it.

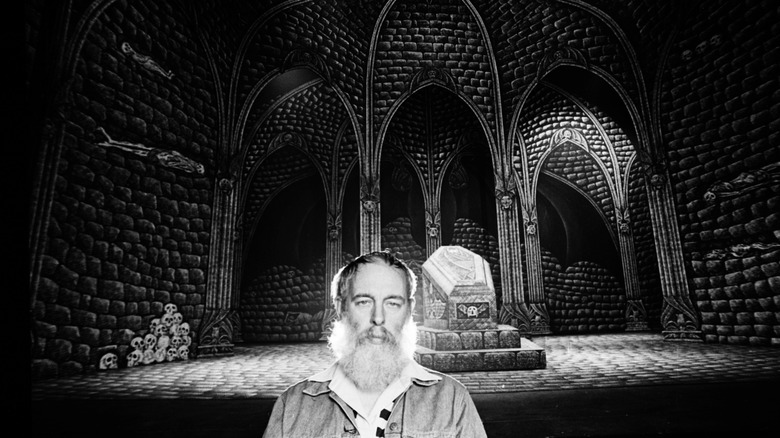

CrimeReads reports that in 1977 Gorey was hired to design sets and costumes for a revival of the original “Dracula” play, which was made famous by the 1931 film version starring Bela Lugosi. Gorey had never worked in theater before, and had never designed sets or costumes before, but he wound up designing both, as well as the advertising art and other aspects of the show. Gorey’s work soon became the play’s most successful feature — in fact, as Boing Boing reports, Gorey was awarded a Tony Award for his costume design. He brought his ink drawing style to full-sized life for the actors to inhabit, and his work is a big reason the play was a smash success.

The New Yorker reports that after decades as a successful freelance illustrator, in 1980 Gorey was hired to create the opening titles for the PBS show “Mystery!,” which showcased British mystery programs and crime dramas. The Cavender Diary explains that Gorey didn’t actually animate the sequence, but provided detailed notes and artwork to animator Derek Lamb, who actually created the animations. These bizarre animated sequences are iconic today, and gained Gorey a much larger audience for his work.

Edward Gorey's sexuality remains a mystery

Edward Gorey was a private person in every sense. Although he was happy to promote his work and lived a very social life, he wasn’t one to reveal himself. So it’s not too surprising that his sexuality remains a hotly debated topic to this day.

Lit Hub reports that Gorey’s often outlandish fashion sense and behavior have led many to assume he was a closeted homosexual living during a pre-Stonewall period when being out was dangerous. But Gorey was very cagey about his sexuality and never actually defined himself as homosexual or anything else. What he actually said opens up more questions than answers — Gay City News reports that he described himself as “apparently reasonably undersexed or something,” and biographer Mark Dery writes in “Born to be Posthumous” that Gorey described himself as asexual “when interviewers pressed the question.”

Gay and Lesbian Review reports that critic Thomas Garvey came to believe Gorey was asexual, though the Atlantic notes that he once told an interviewer “I suppose I’m gay. But I don’t identify with it much.”

In the end, of course, Gorey’s sexuality doesn’t matter in terms of appreciating his art, though many perceive distinctly queer themes embedded in most of his work, making it a fascinating literary concern. It’s simply one more mystery left behind by this brilliant man.

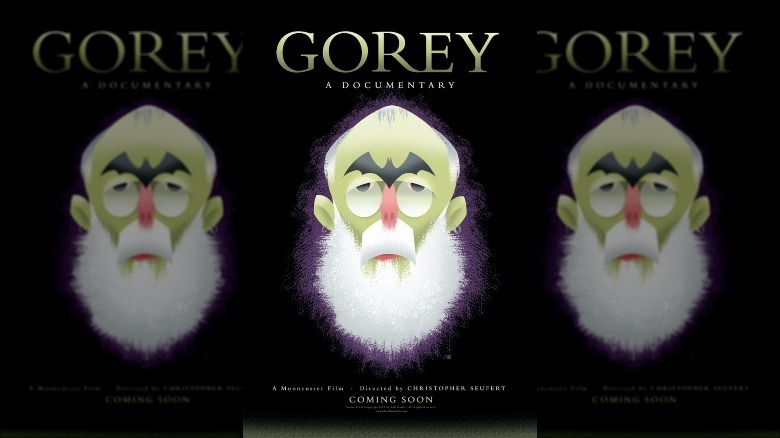

An Edward Gorey documentary's been in the works for decades

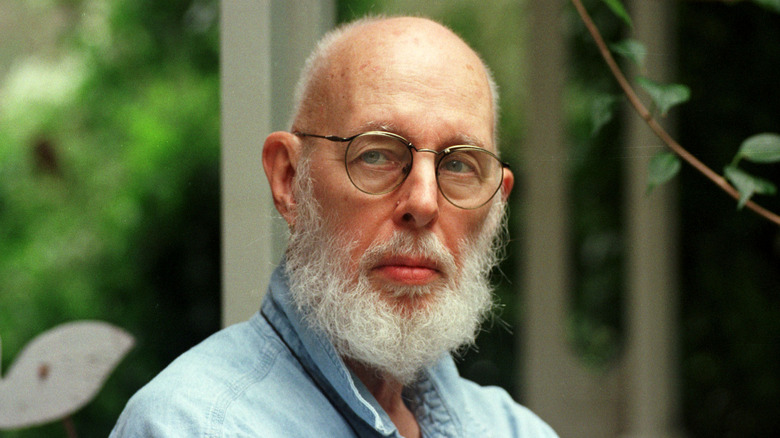

In 1996, when Edward Gorey was 71 years old, filmmaker Christopher Seufert began filming and interviewing the legendary artist. He continued to film Gorey for the next four years, until Gorey’s death in 2000. Seufert’s intention was to create a film in a cinema-verite style, without any outside “talking head” interviews like in traditional documentaries, with only Gorey’s own interview answers as narration.

But decades later, the film still hasn’t been released. In 2014, the Boston Globe reported that Seufert intended to release the film that year, and a Kickstarter to raise funds was launched. To date, it has raised over $62,000 to help with post-production costs. In 2015, Seufert uploaded a trailer for the documentary, and he stated that the plan was to release the film in spring 2021. According to an update on the Kickstarter, Seufert was very close to completing the film and was working on a companion book when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Like many other projects, the film was delayed.

Edward Gorey classified his own work as literary nonsense

Edward Gorey was an artist who defied categorization. In an article in Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, author Kevin Shortsleeve notes that there remains a great deal of debate as to whether Gorey’s work should be considered children’s literature or whether it is too dark and weird for kids. Gorey intended his work to be read by children, considering it to be part of the literary nonsense genre. According to Gay & Lesbian Review, Gorey said “If you’re doing nonsense it has to be rather awful, because there’d be no point… there’s probably no happy nonsense.”

The Atlantic reports that Gorey’s work was long ignored by mainstream critics precisely because it appeared to be children’s literature, with simple rhymes and illustrations. Once people began to take his work seriously as art and literature, it soon became obvious that it defied easy categorization. Dark and ominous, it also embraces silly jokes and outlandish, illogical scenarios. Many of his works use incoherent dialogue, and explore dream logic and atmosphere above all else.

And Gorey did little to clarify things. He enjoyed the fact that his work was difficult to categorize or explain. According to biographer Mark Dery, Gorey once said “Ideally, if anything were any good, it would be indescribable.”

Edward Gorey collected bizarre things

Artists often find inspiration in unusual places, and Edward Gorey was no exception. He was also an enthusiastic collector, and considering the bizarre tone and style of his art, it might not be surprising to learn that his collection included some pretty strange stuff.

Atlas Obscura reports that Gorey collected seemingly useless stuff like potato mashers and salt and pepper shakers, which he arranged into fascinating pieces of ersatz sculpture. He kept receipts and ballet tickets and created collages that he framed and hung on the walls. He also collected some very weird and unsettling things. The BBC reports that Gorey once stated that he liked to “make everybody as uneasy as possible,” which may be one reason he collected daguerreotypes of dead babies — a ghoulish 19th-century fad — or why a mummy’s head was found in his New York City apartment after he moved out. Gorey was reportedly amused when the police contacted him about the artifact.

If Gorey hadn’t been a famous, celebrated artist, he would probably be considered a hoarder. His Cape Cod house was so packed full of stuff that the floors sagged, and after his death, it was converted into a museum to display his strange and wonderful collection of cheese graters, puppets, and vast amount of books.

Edward Gorey became famous in the 1970s

Edward Gorey was employed as a book illustrator right out of college, and he went on to be a successful freelancer in the 1960s, all while publishing dozens of his own books. But until the early 1970s, Gorey wasn’t well-known outside of New York City and the publishing world. The BBC explains that this was partly by design, because Gorey hated self-promotion and had no interest in fame.

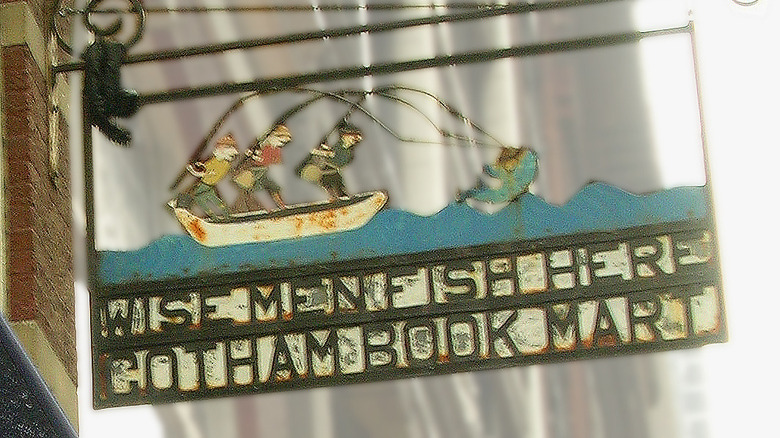

That began to change when a man named Andreas Brown bought the Gotham Book Mart in New York City in 1967. As reported by the Los Angeles Times, Brown had been a fan of Gorey’s for years, and discovered that Gorey was selling his self-published books on consignment at the store. Brown introduced himself to Gorey and became his publisher. Brown also pushed Gorey to release an anthology of his early works, which were very difficult to locate. This resulted in the book “Amphigorey,” released in 1972. It quickly became a bestseller. The book introduced Gorey to a much wider audience, and established him as the cultural icon he is today.

That notoriety led to Gorey designing the sets and costumes for 1977’s “Dracula,” and his work on the opening titles for PBS’ “Mystery!” This exposure cemented his status as a famous artist, but by 1983, Gorey had tired of the notoriety and moved to Cape Cod, Massachusetts for a lower profile.

Edward Gorey was obsessed with the ballet

Gorey was an enormous fan of the New York City Ballet, and especially of famed choreographer and co-founder and artistic director of institution, George Balanchine. Actually, fan is probably too weak a word. The New Yorker reports that Gorey started attending the performances shortly after he arrived in New York in the 1950s, and within a few years he was attending literally every performance.

Gorey became a fixture at the ballet. The Paris Review notes that his routine never varied: He arrived just as the doors opened, and could be found lingering in the lobby during intermissions or if he disliked part of the program. He was opinionated about the performers and the program, often insulting the former and dismissing the latter if he was displeased, but he never criticized Balanchine, who he regarded as a genius and a source of inspiration. In fact, as Bookology reports, Gorey’s move to Cape Cod in 1983 is believed to have been in reaction to Balanchine’s death. Having once said that “my nightmare is picking up the newspaper some day and finding out George has dropped dead,” it’s possible that without Balanchine, Gorey no longer saw a reason to stay in the city.

Edward Gorey was not concerned about death

For an artist whose work often depicted death, ghosts, and grim violence, Gorey was surprisingly stoic about death. Salon reports that he was known throughout his career to announce his health troubles during interviews, lingering over symptoms in apparent attempts to discomfit and horrify whoever he was speaking with. In 1992, for example, he told an interviewer with the Boston Globe that he was suffering from bronchitis, saying “Oh it’s all too much, too grim, too lovely, too — how should I put this? It’s general chaos,” as reported by Salon.

When Gorey was diagnosed with both prostate cancer and diabetes in 1994, aged 69 years, he reportedly displayed almost zero concern. The New York Times explains that he said, “Why haven’t I burst into total screaming hysterics? I’m not entirely enamored of the idea of living forever.” Two years later, he told the Los Angeles Times that he was “just sitting here, coughing.”

Gorey lived six more years after his cancer diagnosis, and it wasn’t his cancer or diabetes that killed him — at least not directly. In April 2000, the Washington Post reports, he had a heart attack, passing away at the age of 75.

Why Ozzy Osbourne Landed A Bad Reputation In The Music World

Why John Landis Sued Over Michael Jackson's Thriller Video

The Story Behind Jimmy Buffett's Margaritaville

How A Genesis Hit Resulted In A Phil Collins Lawsuit

A Look At Gene Simmons' Childhood

The Untold Truth Of Otis Redding

What Was Jessica Walter's Net Worth When She Died?

St. Patrick’s Day Celebrations Around the World

The Tragic Story Of Harry Nilsson, The Beatles' Favorite 'Group'

The Tragic Death Of Dean Paul Martin