The Untold Truth Of The Mausoleum At Halicarnassus

Ever wonder how certain words came to be? For example, the word “mausoleum,” a noun meaning “a building, especially a large and stately one, housing a tomb or tombs,” comes from Mausolus, who was the ruler of the city Halicarnassus in what is now southern Turkey. The city’s bay is where the Mediterranean meets the Aegean.

His wife Artemisia (Mausolus may have begun the project before his death, but Artemisia continued it) commissioned such a mausoleum for her husband’s body after his death in 353 B.C. The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus eventually became so famous that it was known as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World (via Museum of Unnatural Mystery).

The Mausoleum stood for centuries, before earthquakes eventually took out the columns and some of the sculptures. After the earthquakes came looters, who carried away much of the stonework. Now, only the foundations of the structure remain. However, it is still impressive that even this much of such an old, venerated wonder still exists in the modern world. Archeologists and professors began to study the remains of the Mausoleum in the 1800s. It’s one last link back to a very ancient history.

The origins of Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus has an extremely long and detailed history. It was primarily a Greek city, which was likely founded by Dorians from the Peloponnese. One legend of the city stated that it was founded just 17 years after the Trojan war, which overstates its age, writes Livius. It was founded in the 10th or 11th century when Greeks settled the land; Anthes of Troezen was stated to be their leader.

The native Carians were either appeased or driven away from the city for a time. Later centuries make it clear that there was intermixing between the groups, despite opposition. An inscription from between 650 to 400 B.C. refers to the nearby Salmacis as separated from the rest of the city, which implies that Carians and Greeks lived independently. Traces of the original city wall have been found northeast of the 4th century city walls (via Livius). The remains of a temple to the Greek goddess Athena have also been discovered. It is likely that early settlers to Halicarnassus spoke the Ionian dialect.

Halicarnassus was part of various empires throughout the centuries. By around 400 B.C., Halicarnassus belonged to the satrapy of Caria. It was ruled by the Hecatomnid dynasty, or the rulers Hecatomnus and his son Mausolus. Hecatomnus was appointed to the position by Artaxerxes II, writes CNG Coins. Mausolus took great pride in the Greek heritage of the city, and rebuilt it as his capital.

Reworking of Halicarnassus

Under Mausolus and his sister-wife Artemisia’s rule, Halicarnassus became a great city. In particular, its infrastructure and architecture improved. According to World History Encyclopedia, Mausolus built a fleet, and ordered well-constructed roads and temples for the city. He also had public buildings, a circuit wall, and a secret dockyard and canal constructed. Mausolus may have also designed a temple to Ares and a theater, even if construction on both began later.

Mausolus also allowed more people to settle in the city, which brought the population back up. He was loyal to the Achaemenid empire, and built stronger walls to fight against attacks from the newly-created catapult. According to Livius, parts of the walls are still visible today.

Halicarnassus is intrinsically linked with history. Around this same time, Mausolus participated in the Revolt of the Satraps. Though the revolt was defeated, Mausolus was allowed to keep his post; certain ancient sources refer to him as a king. According to CNG Coins, he was allowed to do as he liked, but was forced to keep a Persian garrison in the city.

Origins of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

Mausolus died in 353 B.C. The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus was a large burial structure created for him by his sister-wife, Artemisia. (The Carian rulers had a custom of marrying their sisters.) Artemisia spared no expense in finding the best artisans to work on the tomb. According to the Museum of Unnatural Mystery, Satyros and Pytheos designed the overall shape, while Bryaxis, Leochares, Timotheus, and Scopas of Paros all took one side of the square design to decorate. Scopas of Paros was also responsible for working on the Temple of Artemis.

As with other large projects, there were many different craftsmen and workmen involved. The Mausoleum ultimately included a mix of Lycian, Greek, and Egyptian styles.

The Mausoleum was constructed on a hill overlooking Halicarnassus; it is in an enclosed courtyard on a platform. A staircase decked with stone lions led up to the platform. Made of bricks and marble, the square structure tapered at one-third of its 140-foot height before shifting into 36 columns that rose for another one-third of the height. The roof made up the rest of the structure. The roof was a pyramid with 24 stepped levels. Statues liberally covered the courtyard and the Mausoleum, including those showing action scenes from Greek history. The very top included a sculpture of Artemisia and Mausolus being pulled in a chariot by four horses, done by Pytheos. When Artemisia died two years after her husband, the tomb was unfinished, but both of them were eventually buried there.

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus was deemed the seventh wonder of the ancient world

The Mausoleum was declared one the wonders of the ancient world due to the beauty of the construction. The concept was likely copied for the tomb of Alexander the Great and the Belevi Mausoleum, writes Livius. Satyros and Pytheos, two of the sculptors, wrote a book about the experience; Pliny the Elder then wrote about their book, which is where most historians found the dimensions and discovered what the Mausoleum probably actually looked like.

Inspired by Anatolian and Greek architecture, the Mausoleum was so immense, and its sculptures were so intricate, that it ended up on the list of ancient wonders. Said wonders of the ancient world were monuments that impressed people with their architectural ambition, beauty and artistry on such a scale that the structures’ reputation grew practically on their own. The tomb was designed by the best artists of the day, after all. According to World History, as a result the tomb also gave its name to the word “mausoleum,” meaning any large funeral monument.

The craftsmen stayed to finish the tomb even after Artemisia’s death because, according to Pliny the Elder they considered “that it was at once a memorial of their own fame and of the sculptor’s art,” (according to the Museum of Unnatural Mystery). This would turn out to be true. All the same, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus was commemorating a mortal, not a god.

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus withstood attacks for centuries

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus withstood the effects of war and time for centuries. The tomb was undamaged, for example, when Alexander the Great attacked the city in 334 B.C., just a few years after it was finished. It was also unharmed after pirates attacked the area in 62 and 58 B.C.

The Mausoleum stood above the city of Halicarnassus, which eventually came to be called Bodrum, in Turkey, for 17 centuries. In all that time, it didn’t undergo any sort of serious damage. However, earthquakes in the 13th century finally shattered the columns, writes the Museum of Unnatural Mysteries. The earthquakes also sent the Mausoleum’s stone chariot crashing to the ground. Many of the statues and other stones were scattered around the area. By 1404, only the base of the tomb was recognizable, but even that was in disrepair. Looters quickly came to the area, and seeing a broken monument, began taking the stone for themselves.

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus was further dismantled

In the 1400s, crusaders began to live in Bodrum, and recycled the Mausoleum’s stones into their own projects. The tomb’s marble, for example, was used in Bodrum’s castle walls, and can still be seen today (via Museum of Unnatural Mysteries). The Knights of St. John of Malta invaded the region in the early 15th century and took some of the statues as well, for display on their castle’s walls. Afterwards, the knights ground the remainder of the sculptures into lime for plaster.

By the mid-1500s, every remaining visible block of the Mausoleum had been used for other constructions (via Bodrum Pages). At some point before or during the 15th century, the tombs had been plundered; the bodies of Mausolus and Artemisia were missing, writes the Museum of Unnatural Mysteries. The British ambassador also obtained certain sculptures at this time (mostly fragments of statues and pieces of the frieze showing the battle between the Greeks and the Amazons), which are now on display at the British Museum.

Several archeologists studied the remains

In 1844, Stratford Canning, the British ambassador to Istanbul at the time, asked the Ottoman Empire for permission to take sculptures from the Mausoleum back to the British Museum. This was allowed. In 1846, archeologist Charles Thomas Newton further studied the remains of the ruins. He started to search for the Mausoleum by studying Pliny the Elder to find the approximate location of the tomb. Newton dug tunnels to further investigate the nearby land, and eventually was able to discover a staircase, walls, and three corners of the foundation of the Mausoleum, writes Bodrum Pages.

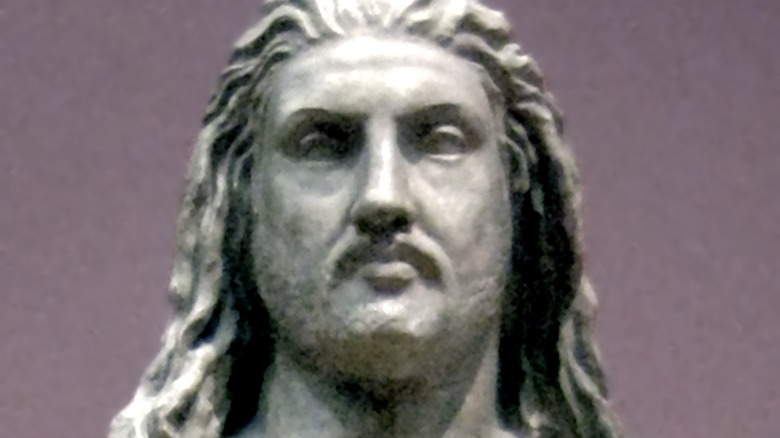

Now that he knew the tomb’s location, Newton bought the plot of land. He excavated the site and found sections of sculpture reliefs, portions of the roof, and the broken stone chariot wheel that had fallen centuries before. It was seven feet in diameter, according to Bodrum Pages. Newton also found the statues of Artemisia and Mausolus that had stood on the roof. They were transported to the British Museum, and now stand in the aptly-named Mausoleum Room. Newton described the excursion in his work “Travels and Discoveries in the Levant.”

From 1966 to 1977, Kristian Jeppesen of the University of Southern Denmark excavated the site. The team discovered a piece of a frieze that escaped Newton, and created a precise plan of the area. According to the University of Southern Denmark, the team used physical evidence plus the descriptions of ancient authors to create a reconstruction of the tomb.

The blocks of Dock No. 1 were possibly from the Mausoleum

Some of the submerged marble blocks of Malta’s Dock No. 1 are believed to have come from the Mausoleum. The ship HMS Supply entered Grand Harbour, a natural harbor in Malta, in 1858, which was a year after the foundation stone for the dock was laid. The ship was carrying artifacts from the tomb, which had begun to be excavated by archeologist Charles Thomas Newton 12 years before, according to the Times of Malta. Newton believed the stones would be better put to use in some kind of public project that everyone would see. The dock in Cospicua, Malta took approximately six years to build.

Malta was historically used as a stopover for loading and unloading artifacts. The Elgin Marbles, a collection of classical Greek marble sculptures, passed through Malta, for example. According to Emmanuel Magro Conti, senior curator at Heritage Malta’s Maritime and Military Collections in the Times of Malta, the plans for Dock No. 1 show that building blocks are included, but aren’t any more specific than that regarding what the blocks are made of or where they’re from.

The Jar of Xerxes and its connection to the Mausoleum

A calcite jar, almost 30cm high, was discovered in the Mausoleum’s ruins. Inscribed with the name Xerxes, it now resides in the British Museum. It was probably made in Egypt and contains translations in Egyptian, Babylonian, Elamite, and Old Persian, writes Livius.

The Achaemenid king Xerxes, who ruled from 486 to 465 B.C. was the only one who could have given this to its probable recipient, Queen Artemisia I, due to the specificity of the royal signature. The historian Herodotus didn’t mention the king’s visit to Halicarnassus, but it likely occurred for the gift to have ended up in the tomb centuries later. The gift likely passed through the Carian royal line and was given as a funeral gift to Mausolus, which is how it ended up in the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. It is an interesting look into seeing just how connected all these rulers and nations were, as it traveled through and touched Persia, Egypt, and Caria.

The Mausoleum's influence on language

The sheer artistry of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus won it acclaim and a position as one of the seven ancient wonders of the world. That fame and importance in turn changed words in several languages. The tomb itself had so much influence that it became a brand-new world, all on its own. How cool is that?

The tomb of the satrap Mausolus was named after him. From that came the Greek word “mausoleion.” From the Greek came the Latin “mausoleum,” which made its way into English in due course. Now, according to Etymonline, “mausoleum” is also a word with a general meaning of “any stately burial-place,” though it is one which usually contains a good number of tombs. Not only are there words in Latin and Greek which still reference Mausolus and the tomb specifically, but English has created a general definition as well, for those times when “cemetery” just isn’t enough.

The city of Bodrum today

The city of Bodrum, formerly the great trading city of Halicarnassus, is the site of the Mausoleum. The main street of Halicarnassus when the Mausoleum was built is still the main street of Bodrum today, according to the University of Southern Denmark.

Bodrum is a tourist destination for several reasons, including its history and beaches. Known as the “land of eternal blue,” Bodrum’s bay is where the Mediterranean Sea and the Aegean Sea meet. The remains of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and Bodrum Castle remain popular attractions along with Bodrum’s several beaches due to its status as a lovely coastal city, writes Bodrum Travel Guide. Bodrum is also known for having an underwater archeology museum. The city has several boat yards with traditionally-built yachts whose methods go back centuries.

The name “Bodrum” comes from another of the city’s names, “Petronium,” which it acquired after the Knights of St. John took over the city in the 15th century.

The ancient wonders of the world today

Little except the foundation remains of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus today. According to World History Encyclopedia, column fragments still exist, while most of the surviving sculptures have been taken to the British Museum. Of the other six wonders of the ancient world, only the Great Pyramid of Giza has survived to the present day. The Great Pyramid is known as Khufu, since it was one of three pyramids, the others named Khafra and Menkaura. Archeologists believe most of what was inside the pyramids was stolen within 250 years of completion, writes History.

Several of the ancient wonders, including the Mausoleum, were destroyed by natural disasters. The statue of Zeus at Olympia was first struck by lightning before being destroyed in a fire centuries later. The Colossus of Rhodes, a sculpture of Helios, was toppled in an earthquake only 60 years after it was created (via History). Meanwhile, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, completed around 270 B.C., was gradually destroyed by earthquakes over the course of centuries. Pieces of the lighthouse were later found in the Nile River.

Great art cannot stop the flow of time or the wrath of nature. The remains of the Mausoleum are a link to a history that is so ancient it may as well be beyond our reach. However, said remains – as well as the sculptures in the British Museum – can be visited. History therefore can be – and should be – brought back to life.

The Telltale Signs That Someone Might Be A Murderer

What Life Was Like As A Print Worker In The Colonial Era

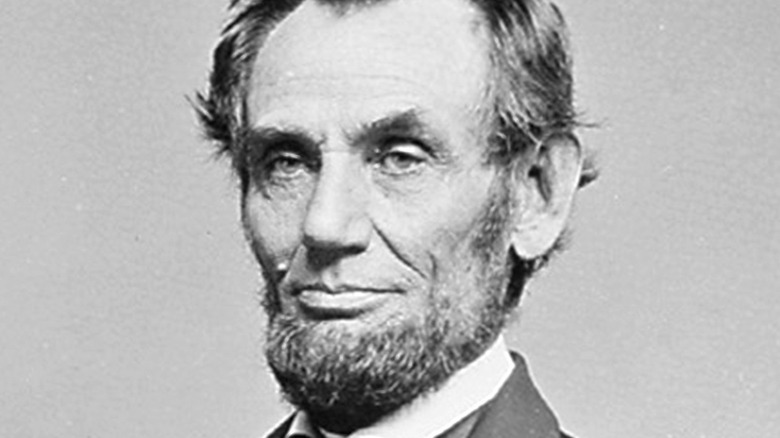

The Legend Of Abraham Lincoln's Ghost In The White House Explained

The Truth Behind Chicken Pox Parties

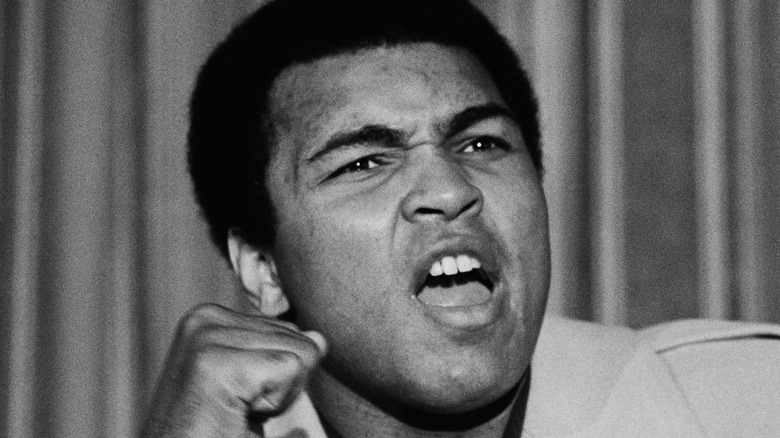

The Truth About Muhammad Ali's Spoken Word Album

The Iconic Song Liza Minnelli Has Avoided Singing For Most Of Her Career

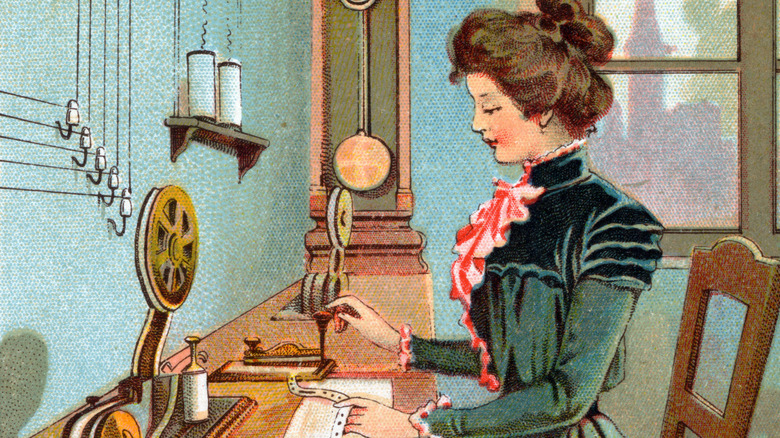

Everything Known About The Last Telegram Western Union Ever Sent

The Richest Rock Bands In The World

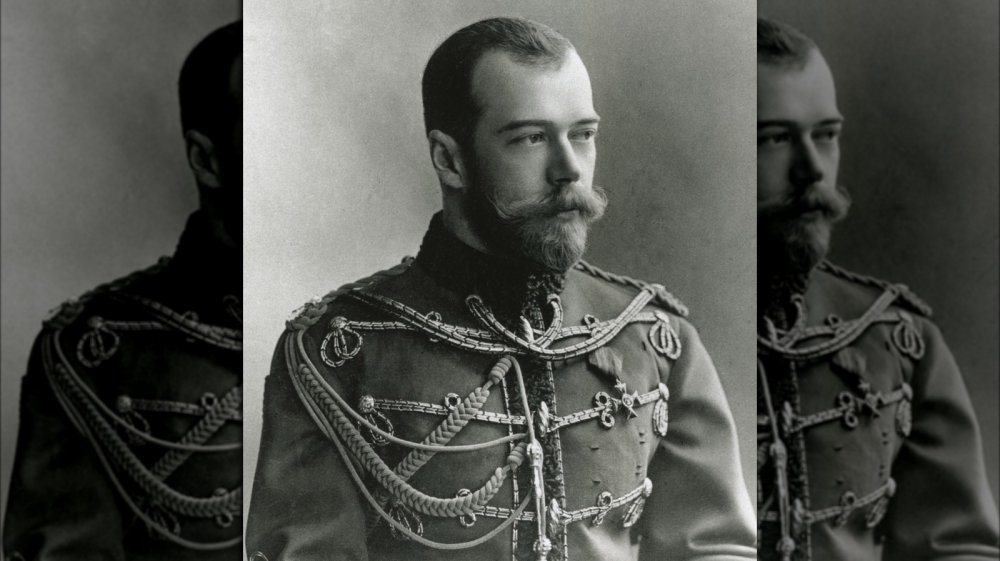

Inside The Final Days Of Russia's Last Czar

This Is The Most Expensive Baseball Card Ever Sold