What Really Happened To ‘Africa’s Che Guevara’?

Thomas Sankara has been described as “Africa’s Che Guevara,” but he’s not the only African revolutionary to be assigned that moniker. Amílcar Cabral from Guinea-Bissau and the Cape Verde Islands has also been described as “Africa’s Che Guevara,” as has Patrice Lumumba from the Democratic Republic of Congo. But all of these people were revolutionaries in their own right and need no comparison. Although Sankara was the president of Burkina Faso for only four years, in those years he fought neocolonialist policies, instituted land reforms, sought to eliminate corruption, and prioritized health and education.

However, even Sankara’s revolution had its limits. The Popular Revolutionary Tribunals that he created put corruption on public display, but at one point Sankara claimed that the tribunals were sometimes “used as occasions to settle private scores.” Sankara’s regime also attacked trade unions and had numerous conflicts with the working class, with some describing his reforms as actively “work[ing] against popular empowerment.”

Ultimately, both Thomas Sankara and his policies were short-lived. After his assassination, he was succeeded by Blaise Compaoré, who reversed “most of Sankara’s policies” and proceeded to remain in power for 27 years. But who exactly was responsible for Sankara’s death? And what did Sankara accomplish during his life that made him such a threat? This is what really happened to “Africa’s Che Guevara.”

Thomas Sankara's early life

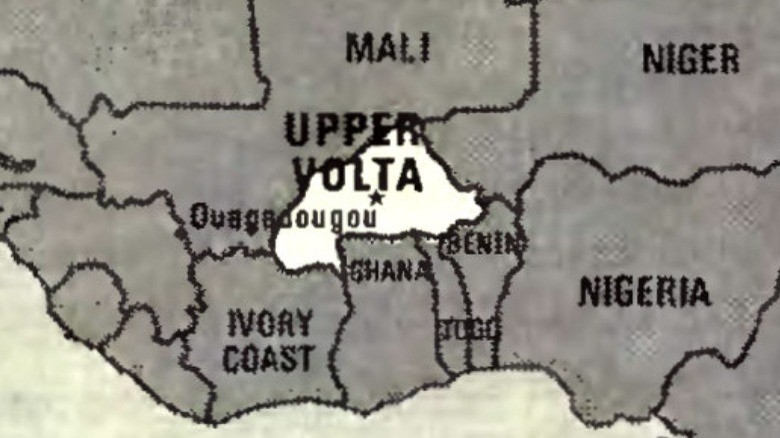

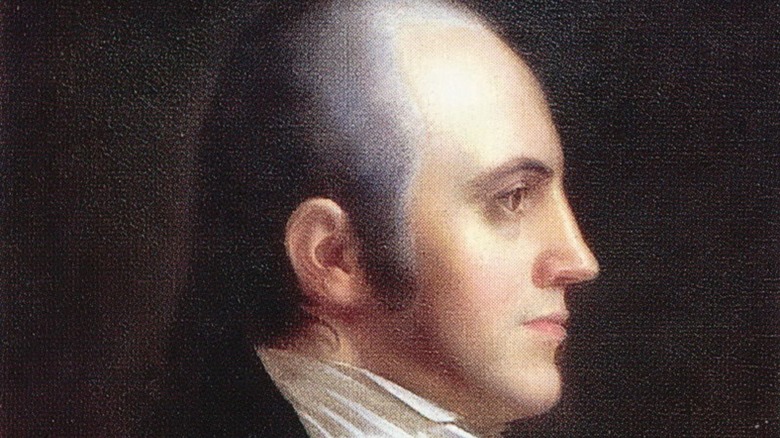

Thomas Sankara was born Thomas Noël Isidore Ouédraogo on December 21, 1949, in Yako, Burkina Faso, known at the time as Upper Volta, to Joseph Sankara and Marguerite Kinda. While his last name “Ouédraogo” was the most common Mossi family name, Sankara was Silmi-Mossi, “a socially marginal category descended historically from both Mossi and Peulh,” Ernest Harsch writes in “Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary.” His father Joseph took on the name Ouédraogo at the request of the Mossi chief of Tema when he joined the French army during the Second World War, but when Sankara was a teenager, his father changed the family name back to Sankara.

Because Sankara’s father worked as a paramilitary police officer and was employed by the French colonial state, Sankara and his 10 siblings grew up in a “relatively privileged position.” But before long, Sankara started to notice the difference in treatment between the local children and the European children. From a young age, Sankara also noticed how gender inequalities started in childhood, later describing how while a boy was seen as a “gift of God,” a girl is “greeted as an act of fate, or at best, a gift that can be used to produce food,” per “Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa.”

Although his parents wanted him to become a priest, when a new military academy was established in Ouagadougou, Sankara took an entrance exam.

Uprisings in Madagascar

After passing the entrance exam, Thomas Sankara joined the military academy in 1966. The priests at Gaoua were reportedly so disappointed that they reportedly criticized Sankara’s father for “not praying hard enough,” records “Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa.” At the time, the military was popular in Burkina Faso due to their role in ousting President Maurice Yaméogo and, according to “Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary,” some people believed that it “might help discipline the inefficient and corrupt bureaucracy.”

In 1970, Sankara was chosen for advanced training at the military academy in Antsirabe, Madagascar, where he would spend three years training to be an army officer, although his original plan was to become a military surgeon. During his time at the academy, Sankara witnessed two protest movements. The farmer protest that began in April 1971 and the student protest that began in April 1972. According to “Madagascar,” the first protest was influenced by the government pressuring tax collection from farmers while local cattle were widely suffering from disease. The second started when students started protesting France’s cultural domination in schools and quickly became a general strike against poor economic conditions. While the first revolt was unsuccessful and was brutally suppressed, the second revolt resulted in the ousting of President Philibert Tsiranana and the collapse of the First Republic of Madagascar.

Having completed his officer’s training, Sankara stayed in Madagascar for one more year to work with a civil service unit involved in “rural development.”

Life as a soldier

After returning to Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara fought in the 1974 Agacher Strip War, as a lieutenant in the army. According to “Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa,” it was there that Sankara met Blaise Compaoré, who was a young officer at the time.

At the time, corruption was rampant amongst military officers, even going as far as to steal food aid and sell it for a profit in Niger and Mali, known as the “Watergrain” scandal. In response, Sankara, his friend Jean-Baptiste Lingani, and other officers who wanted to “reform the military system and educate themselves politically” formed a group known as ROC. Early members also included Henri Zongo, Abdoul Salam Kaboré, and Boukary Kaboré. Soon Compaoré was brought into the group as well. While some sources describe the group’s name as an acronym for Regroupement des Officiers Communistes, or Communist Officers’ Group, according to Salam Kaboré the name was just “Roc as ‘hard like a rock” and while the group was certainly influenced by leftist ideas, they were “simply trying to become aware of [themselves] as political actors, not just as soldiers.”

In 1976, Black Past writes that Sankara also started leading a Commando Training Center in Pô. There, he pushed soldiers to offer their support and assistance to civilians with their tasks.

Thomas Sankara steps into government

In 1981, Thomas Sankara was appointed to the position of Minister of Information. But from the onset he was unlike any of the previous ministers and the residents of Ouagadougou were surprised to see a minister going to work on his bicycle. Viewpoint Magazine writes that before Sankara, the Information Ministry was mainly just propaganda. But Sankara encouraged journalists to write about corruption and soon there were reports on embezzlement in a public bank and suggestions that the Ministry of Trade was complicit. When the director of the National News Agency was accused by police of feeding information to the press, Sankara defended the press to the Minister of the Interior.

In April 1982, Black Past writes that Sankara resigned from his position and wrote an open letter to President Saye Zerbo, denouncing his regime and the newly-created Military Committee for Reform and Military Progress, “which he decried as bourgeois and serving the interests of the minority.” Sankara was promptly deported to a military camp in Dedougou and stripped of his rank. But after a military coup led by Commander Gabriel Somé Yorian on November 7, 1982, Sankara was restored to his rank of captain.

However, according to Links, Sankara and his supporters didn’t participate in the coup because they believed that a movement led by the army wouldn’t allow for “fundamental social changes.”

House arrest

The military-led government was known as the Council of Popular Salvation (CSP), which was presided over by Jean Baptiste Ouédraogo. Recognizing Thomas Sankara’s influence, Ouédraogo appointed him as Prime Minister of Upper Volta on January 10, 1983. Almost immediately, Sankara set out on an international trip, visiting Libya and North Korea in addition to attending the summit of the Non-Aligned Countries in New Delhi, India. According to Links, Sankara met various revolutionary leaders at the summit, including Fidel Castro, Maurice Bishop, and Samora Machel.

However, as Sankara continued to criticize corrupt civil servants, the CSP began to worry, as did the “neighboring Côte d’Ivoire with backing from France,” Viewpoint Magazine writes. As a result, on May 17, 1983, armored cars surrounded Sankara’s home and put him under house arrest and the decision was made to replace him.

Sankara wasn’t the only one pursued by President Ouédraogo and the CSP. Commander Lingani was also detained, and anyone in the cabinet associated with Sankara was also removed. This move was approved by French imperialists, who agreed to send the CSP more financial aid after the purge.

A new revolution

However, Thomas Sankara’s removal and house arrest didn’t go over smoothly with the residents of Ouagadougou. On May 20-21, protests were organized across the capital, “involving students, radicalized poor people and trade unionists,” writes Links. In response to the protests, Sankara was released by the authorities.

Compaoré was also sought for arrest and fled to Sankara’s old commando training base, which refused to recognize the authority of those in Ouagadougou. And on August 4, 1983, after a rumor spread that there was an assassination attempt on Sankara’s life, Compaoré moved into Ouagadougou with troops. According to Viewpoint Magazine, this operation, known as the August Revolution, was supported by civilian groups, who assisted by cutting electricity.

By 10PM that night, Sankara made an announcement over the radio that the CSP government had fallen and there was to be a new government formed, known as the National Council of the Revolution (CNR). Sankara also encouraged people to form Committees for the Defense of the Revolution themselves “in order to fully participate in the CNR’s great patriotic struggle and to prevent our enemies here and abroad from doing our people harm.” Under the new regime, Sankara was made president.

Thomas Sankara's anti-imperialism

Two months after the revolution, Sankara gave his “Political Orientation Speech,” in which he underlined the foundations and the goals of the revolution. Identifying how the country “evolved from a colony into a neocolony,” Sankara stated that the primary goal was going to be the “transfer [of] power from the hands of the Voltaic bourgeoisie allied with imperialism to the hands of the alliance of popular classes that constitute the people.” This was not a new sentiment in Sankara, who openly criticized the foreign policy of the United States while he was prime minister, criticizing U.S. imperialism in El Salvador and Nicaragua as well as condemning Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, done with the support of the United States, writes Links.

Sankara was also critical of Western aid. After suggesting to the United States that they replace their Peace Corps program with budgetary support, Sankara suspended the Peace Corps program when the United States refused, according to Viewpoints Magazine. In the end, between 1985 and 1988, Burkina Faso didn’t receive any foreign aid from the West, the World Bank, or the International Monetary Fund. And without any foreign aid, over 400 miles of railways were laid and up to 350 schools were built in Burkina Faso during Sankara’s presidency.

And against the “colonial plunder,” which Sankara describes as “decimat[ing] our forests without the slightest thought of replenishing them for our tomorrows,” up to 10 million trees were planted, writes Liberation School.

Renaming the country

On the first anniversary of the August Revolution, Thomas Sankara changed the name of the country from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso. “Upper Volta” came into being when France claimed the territory as a protectorate in 1897 and named it after the Volta River. Within 30 years, it was turned into a colony in 1919. Upper Volta remained a colony until 1932, when France dissolved its status and incorporated the territory instead with its colonies in Côte d’Ivoire, French Sudan, and Niger.

According to Regionalism in West Africa, this continued until 1946. But once the new constitution gave people in French colonies the right to form political parties, the Union for Defending the Interests of Upper Volta requested the restoration of the territory of Upper Volta. And on September 4, 1947, the colony of Upper Volta was voted to be restored by the French National Assembly.

Because the name “Upper Volta” was a colonial creation and unable to be divested of its colonial association, Sankara decided to choose a name that was connected to the indigenous people of the land. Liberation School writes that the new name translates roughly to mean “land of the upright people” in both Mossi and Dioula. Other English translations include “land of the incorruptible people” and “the republic of honorable people.”

Rejecting colonial debt

Thomas Sankara also rejected the colonial debt imposed by France after colonies gained independence. Through a “colonial pact,” Global Voices writes that France essentially forced up to 14 countries to put 50-85% of their foreign reserves into the France Central Bank. And according to “Africa in the Colonial Ages of Empire,” if countries want to access their own money outside of the 15% in the country, they’re forced to “borrow the extra money from their own 65% from the French Treasury at commercial rates.” The pact also included an obligation to use the French currency, the FCFA.

Mediapart writes that not every country accepted these terms. When Guinea was the first to declare independence in 1958, the French did everything but salt the earth on their way out of the country. When Togo followed suit in 1960, President Sylvanus Olympio agreed to pay an annual debt but decided to issue a new currency in the country in 1963. As a result, three days after starting to print a new currency, President Olympio was assassinated by a squad of ex-French Foreign legionnaires backed by France.

Sankara called debt “neo-colonialism, in which colonizers have transformed themselves into “technical assistants'” and attempted to cancel Burkina Faso’s colonial pact with France. However, some claim that it was this attempt to cut ties with France that led to his assassination. As of 2020, eight countries that were formerly colonized no longer have to keep half of their reserves in France.

Women and Thomas Sankara's administration

Thomas Sankara ensured that women were a part of Burkina Faso’s revolution and actively addressed issues of women’s emancipation, stating that “there is no true social revolution without the liberation of women,” per The African Exponent. Stressing the importance of education, Sankara underlined that care should be taken “to assure that women’s access to education is a reality.”

Liberation School writes that women were also granted pregnancy leave from school and were also encouraged to join the military. Women also soon formed political organizations, like the Women’s Union of Burkina.

Sankara instituted a 30% quota for women in all government offices and maintained it among his own civilian ministers as well, appointing Joséphine Ouédraogo as minister of family development, Rita Sawadogo as minister of sports and leisure, and Adèle Ouédraogo as minister of the budget. According to the Historical Dictionary of Women in Sub-Saharan Africa by Kathleen Sheldon, Joséphine Ouédraogo worked to outlaw female genital cutting, prepared a national family law, and supported a women’s strike in 1984. Forced and child marriages were also outlawed under Sankara’s presidency.

Thomas Sankara's assassination

On October 15, 1987, Thomas Sankara met with his team of advisers at the office of the CNR at the old Conseil de l’Entente headquarters at around 4:15 in the afternoon. But according to Africa’s Country, the meeting lasted only about 15 minutes before gunfire started in the courtyard outside. Sankara’s driver and two of his bodyguards were the first to be killed. Although Sankara reportedly gave himself up to the assassins in an attempt to save the lives of his advisers, after murdering Sankara the gunmen went into the meeting room and fired all around. Everyone except for Alouna Traoré, Sankara’s legal adviser, survived the attack, per VOA. In total, 13 people were killed.

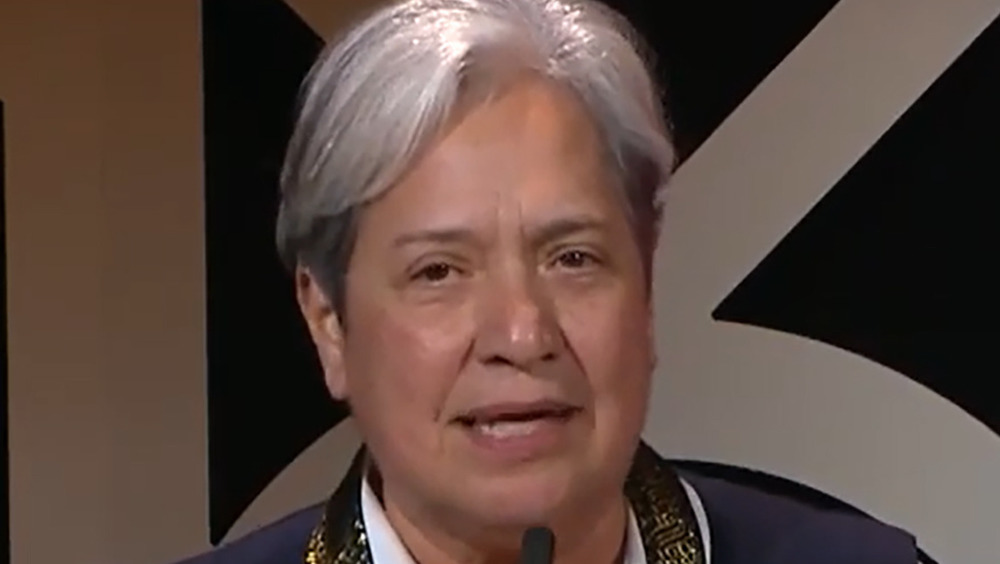

Although Compaoré claimed that he wasn’t involved in the assassination and had been at home sick at the time, he took power that evening and would remain in power until the 2014 Burkinabé uprising. Liberation School writes that after assuming the presidency, Compaoré privatized national resources and resumed a position in the International Monetary Fund.

Meanwhile, Sankara’s death was ruled to be from “natural causes.” And Compaoré refused to allow any investigation into Sankara’s assassination. It wasn’t until 2015, when Sankara’s body was exhumed, that an autopsy showed that it was riddled with bullet wounds.

Indicting the former president

While in power, Blaise Compaoré repeatedly refused to allow Thomas Sankara’s body to be exhumed. But after Compaoré was exiled in 2014, Sankara’s body was finally exhumed the following year. After it was found to be filled with bullet holes, The Guardian reports that an international arrest warrant was issued for Compaoré’s in 2016. However, Compaoré had since become a citizen of Côte d’Ivoire and Ivorian authorities refused the request for extradition. Along with 13 others, Compaoré was charged with complicity in murder and concealing bodies.

Al Jazeera writes that the trial against the 14 men began on October 11, 2021. However, they were adjourned until October 25 after defense lawyers requested a stay after saying they received 20,000 documents.

Having fled the country, Compaoré will be tried in absentia. Meanwhile, his lawyers announced that he was boycotting the trial, calling it “a ‘political trial’ flawed by irregularities.” They have also insisted that as a former head of state, Compaoré has immunity. Hyacinthe Kafando, who is accused of leading the hit squad, is also on the run.

The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Princess Diana

Why Sir Alfred Was Stuck In An Airport For 18 Years

The Truth About The Mass Grave From Stalin's Great Purge

North Korea's Extreme Dating Rules Explained

The Untold Truth Of Nazi Filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl

The Unsolved Mystery Of The Ancient Roman Dodecahedron

Did Amelia Earhart Have Any Kids?

This Piece Of Evidence Was Overlooked In The Green River Killer Case

This Was The Secret To Jesse Owens' Speed

Western Period Movies That Got History Totally Wrong