Cultures That Celebrate The New Year Later In The Year

It’s common knowledge that in many parts of the world, people celebrate the arrival of the new year (and, in some cases, the fiery demise of the previous year) on December 31 and January 1. Less well-known is the fascinating story of why that is.

According to History, it was Julius Caesar who revamped the Roman calendar and debuted it in 45 B.C. — and January 1 of that year was the first “New Year’s Day.” Previously, the Roman calendar sort of followed the cycles of the moon, but prior rulers had added dates and entire days to the calendar (often in an attempt to extend their time in power and political office) and, basically, it was a mess.

The Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes advised following in the footsteps of the Egyptians and basing a new calendar on the sun. The new year became January 1, but that doesn’t coincide with the solar year, either, so… what gives?

Sosigenes ended up making a mistake and was off by 11 minutes. That added up over the years, and by the 15th century, those 11 minutes had turned into about 10 days. That led to another revamp and the Gregorian calendar (named for Pope Gregory XIII). January 1 remained the start of the new year, but here’s the thing — there are numerous cultures that just decided they weren’t down with January 1 being the new year and decided to do their own thing.

Balinese New Year: a time of serenity and meditation

New Year’s, says Bali, is the biggest and most important celebration of the year on the island of Bali. The start date of the six-day festival varies, is calculated based on the Balinese calendar, and the festivities kick off in March with the Melasti Ritual, in which sacred objects are purified with sea water.

Then comes the Bhuta Yajna Ritual — which involves the sacrifice of animals like cows and pigs — and the Ogoh Ogoh Parade. The basic idea of the parade is that each village makes their own massive paper-and-bamboo statue of a demon, called the ogoh-ogoh. Those carrying the statues and marching in the parade try to make as much noise as possible, in hopes of driving off the demons for the new year. The statues are then (traditionally) burned, and what follows is Nyepi, or the Day of Silence. There’s no fire (or electricity), no traveling, no activity, and no entertainment. Instead, everyone is expected to sit in silent reflection and meditation, in order to start the new year with a clean slate.

It’s the day after Nyepi that’s the official new year, and it’s a day spent visiting friends and family with a specific purpose in mind — asking (and giving) forgiveness. It all wraps up with readings of ancient texts, a reminder that New Year’s in Bali is a deeply spiritual week.

New Year's in Sri Lanka: starting the year off with positivity

On Sri Lanka, New Year’s is celebrated on the same day every year — April 14. According to Time Out, it isn’t just a big deal, it’s a time for fun and festivities, as a big part of the holiday is making sure the new year gets off to a promising and pleasant start — which honestly sounds downright wonderful.

In Sinhala homes, there’s a lot of spring cleaning and home improvements done in the weeks prior, in order to make sure everything is spic-and-span for the new year. Firecrackers and drums see out the old and welcome in the new and the start of the year’s rituals. That includes things like lighting the hearth, and making and sharing traditional dishes. Visiting friends and family members is a must, and the goal is to put disagreements in the past and go forward with a stronger bond. After an anointing ceremony, it’s time for fun and games!

Tamil families start with a similar bout of cleaning and freshening up, along with the hanging of garlands and the drawing of symbols to ward off evil. A purification ritual prepares the faithful to thank the gods for the blessings of the previous year and ask for protection in the coming one, and financial transactions start with adults giving children money that they’re not to spend until another year has passed.

Islamic New Year: prayer and reflection

The first day of the Islamic New Year varies, as it’s based on the lunar calendar and the first time the lunar crescent is visible in the sky following the new moon that occurs in the month called Muharram. Complicated? Absolutely, and the date can vary a lot. For example, The Farmer’s Almanac says that for 2021, the first day of the Islamic New Year is August 9 at sundown, while in 2024, it’s July 7.

Hindustan Times says that the day kicks off the start of the calendar and is observed based on the time of the Prophet Muhammad’s journey from Mecca into Medina in the year 622 C.E.

Traditions and observations can vary based on faith, but generally, the holiday — which is one of the most sacred in the Islamic calendar — is reserved for silent reflection and prayer. That’s reflected in the very name of the month — “Muharram” translates roughly to “not permitted.” Sunni Muslims typically fast for two days of the month, while Shia Muslims don mourning clothes in remembrance of Imam Hussain, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad and martyr who was beheaded in battle.

Serbian New Year: where modern meets traditional

What’s better than a great New Year’s party? Two New Year’s parties!

For that, you’ll need to head to Serbia. Most of Serbia celebrates the regular, January 1, New Year’s, but then, they just kind of keep partying. Trees and decorations will still be up for weeks, and that’s because of a weird thing that happened with their calendars.

When the Julian calendar was replaced by the Gregorian one, Serbia switched, too — but they were never really happy about it. Fast forward to the 20th century, and specifically, 1919 and the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. That’s when the celebration of the traditional Serbian New Year was deemed to be a big no-no, but by 1923, people absolutely did it anyway as a form of protest. Communism put another damper on traditional celebrations by outlawing things like public gatherings. But by the 1990s, the landscape had changed once again, and many Serbs started celebrating both the January 1 holiday and the traditional, January 13-14 one.

According to Culture Trip, New Year’s in Belgrade is a party to end all parties, and their words of wisdom? Don’t start too early and pace yourself, because you’re in for a long, long night.

Cambodian New Year: three days of reflection, charity, and cleanliness

The Cambodian New Year is also known as the Khmer New Year, or Chaul Chnam Thmey, and according to The Cambodian Buddhist Society of Western Australia, beliefs around this holiday have traditionally been tied to the sun’s movement into Aries and the Vernal Equinox. It’s the end of the harvest and the beginning of the rainy season, but it’s also something much more meaningful — the first day of the new year is also celebrated as the anniversary of the first day of the creation of the world.

It starts on either April 13 or 14, and the first day is a time for lighting candles in a freshly cleaned house and placing a Buddha on the home’s altar.

The second day is a time of charity and giving, where people go out of their way to help the needy. That could involve a variety of charitable giving and acts, and it’s also when gifts are exchanged and ancestors are venerated at monasteries. The final day there’s a lot of washing going on. Buddha statues are washed to appeal for the rains needed by the next harvest, and children bathe the elders in order to ask for their blessings and their wisdom.

This wasn’t always New Year’s — prior to the 13th century, it was held in the end of November or beginning of December, until it was moved to the end of the harvest season (via tripsavvy).

Celtic New Year: the weakening of the veil

Today, traditional Celtic nations — like Ireland, the United Kingdom, the Isle of Man, and Brittany — celebrate New Year’s with the rest of the world, but it wasn’t always like that.

The Smithsonian says that the ancient Celts believed the year existed in two halves, the light and the dark. The dark half started with the end of the harvest season, lengthening nights, and Samhain at the end of October. (It’s known as the original Halloween, but Celtic New Year’s isn’t exactly like today’s Halloween.) It was believed that the border between the living and the land of the dead was weakest on that day, and it kicked off the rule of Samhain, lord of winter and the dead. (On May Day, things would swing back to being run by the sun god, Bael.)

A lot of what went on at ancient Samhain celebrations is speculation, but old texts do tell of the lighting of massive bonfires, meant to welcome the spirits that prowled the long night. Many dressed in costumes to help fool the spirits into thinking they, too, were among the dead, and turnips were turned into terrifying early jack-o-lanterns, designed to scare even the most vengeful spirit.

Iranian New Year: 13 days to celebrate the spring

National Geographic says there’s a lot of people who celebrate Nowruz — somewhere around 300 million of them. It’s the Iranian New Year, and it falls between March 19 and 22.

Why? The Iranian solar calendar starts with the Vernal Equinox, which is also the first day of spring. That’s something that definitely warrants celebration, and they’ve been doing it for a long time. Ancient Zoroastrianism beliefs heralded it as the day that spring triumphed over darkness, and who can’t get on board with that? That particular religion may have seen a major decline, but Nowruz itself has remained popular for centuries — Middle East Eye says it’s believed to date back around 3,000 years.

And it’s a fun one that starts on the Wednesday before the big day. That’s Charshanbe Suri, a night when revelers jump over fires, visit their ancestors in cemeteries, and make as much noise as they can to scare away the darkness and ill omens.

Numerous countries celebrate the spring festival, and traditions vary. Most are filled with symbolism of nature and fertility, many stage major sporting events, performers, dancers, and singers fill the streets, and festivities last for 13 days.

Rosh Hashanah: reflection, prayer, and celebration

Rosh Hashanah means “first of the year,” but the actual date can vary — a lot. History says that it usually falls in September or October, and the reason there’s so much variance is that it’s based on the start of Tishrei, the seventh month in the Hebrew calendar. It’s much bigger than the start of the new year in our earthly calendar, it’s the anniversary of the literal start of the world — creation. Interestingly, the Jewish calendar recognizes additional “new year’s days” — the start of the calendar is the month of Nisan 1, which was used to mark the years of a king’s reign, while Elul 1 was used to mark the start of the fiscal year, and Shevat 15 marked a year for fruit-bearing trees.

Rosh Hashanah is a serious holiday, and it kicks off the 10 Days of Awe. That, tradition says, is when God takes stock of every living thing and decides if they will die in the following year.

National Geographic says that work stops on Rosh Hashanah, and it’s a time when people reflect, pray, ask for forgiveness, and take stock of their own lives. Many attend religious services and wrap up the day with a meal with friends and family.

Vietnamese New Year: festive chaos

The Vietnamese New Year is simply called Tet — short for Tết Nguyên Đán — and it’s the Lunar New Year that’s celebrated every year in either January or February. Tripsavvy says it’s nothing short of chaotic — the weeks leading up to the festival are full of shopping for everything from decorations and gifts to groceries for the inevitable family meals. Outdoor entertainment venues pop up across the country, millions of people travel to be home with their families, and the streets are filled with noise, made to scare away any evil spirits that might be lurking.

The three days of Tet are seen as a time for a fresh start — houses are thoroughly cleaned, debts are paid, and old disputes are settled. It’s also time to collect luck for the coming year — the first person to step into a home in the new year is thought to bring either good luck or bad with them, so it’s of the utmost importance to choose wisely!

Cwm Gwaun, Wales: this is New Year's, and you can't tell us otherwise

Those living in the Gwaun Valley hills of Wales celebrate the new year on January 13, and why that is, well, it’s pretty hilarious. When most people just sort of went along with the new Gregorian calendar that replaced the Julian one, the people in Gwaun Valley just said, “Nah, we’re good, thanks,” and kept on using the old calendar.

As a result, the BBC says, their new year is more accurately called an old new year, or Hen Galan. Schools are open but no one shows, because they’re all out walking the valley and singing in an age-old tradition that is in no way organized but just sort of happens. In return for their songs, each house on the children’s’ stop hands out candy, money, or other goodies, and the songs are the same ones that have been sung for generations. Also a part of the festivities has traditionally been the Mari Lwyd, which is a horse’s skull, covered in white cloth and carried along on a stick.

Some things have changed a bit, according to those reminiscing to Wales Online. Sometimes parents drive their children from house to house now, but the feasting is the same.

Thai New Year: the water festival

April is usually Thailand’s hottest month, so that means it’s the ideal time for Songkran.

According to Culture Trip, Thailand’s celebration of the new year is the merging of two traditions — the Water Festival, and Songkran, a celebration that originally marked the day when the sun shifted in the zodiac. The result is essentially a country-wide water war — the water has long been believed to be purifying, and honestly, what better way to wash away the bad luck of the previous year and get all squeaky clean for the new one?

Parts of Songkran remain religious, and many will spend time visiting Buddhist monasteries to give charity and ask for guidance for the upcoming year. New Year’s resolutions are common, and more common? Super Soakers, water cannons, and high-pressure hoses. Anyone on the street during the three- to six-day long festival is guaranteed to get smeared with clay (a tradition that’s meant to be reminiscent of a monk’s blessing) and soaked to the bone.

Nepali New Year: ahead of the rest

The only way to truly describe Nepal is “otherworldly,” and it almost makes sense that when the rest of the world was celebrating 2018, they welcomed in the new year of 2074. On April 14.

The reason for the massive discrepancy is that they’re on their own calendar, called the Bikram Sambat. Welcome Nepal says that the lunar calendar is a full 56.7 years ahead of the Gregorian one that’s much more widely used, and Adventure Alternative says that’s the least confusing thing about it. The year is broken up into months, but the number of days in each month changes every year. (And it’s also worth noting that for the Sherpas, they’re on yet another calendar — the year 2018 for them was actually 2144.)

Nepal might seem devoutly religious, but they celebrate the new year in style — there’s a ton of parties, parades fill the streets, and it’s all about the family, friends, and socializing around a lot of food and drink.

Chinese New Year: a truly traditional celebration

In 1912, China adopted the Gregorian calendar along with most of the rest of the Western world. That technically moved their new year to January 1, but celebrations of the ancient lunar new year remain widely popular.

According to History, determining the date for the new year was insanely complex, and it depended on a range of factors that included lunar phases, which region you were in, and even who was in power at the time. Basically, it’s the 15 days after the new moon that happens some time between the end of January and the end of February.

It’s that new year that’s assigned one of 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac, and traditionally, the new year was a huge deal. Everything else would stop for a holiday spent with the family, where a series of rituals (like ritual sacrifices of food and the exchange of red envelopes) were done in hopes of welcoming some good luck along with the new year. And let’s be honest — no matter who you are, where you live, or what you believe, everyone could use a little more luck.

Pearl Fernandez Murdered Her Son. Where Is She Now?

Here's How The President's Nuclear Football Really Works

Scientists Are Hoping To Make This Surprising Discovery On Mars

The Real Reason Paul Is Sometimes Called Saul In The Bible

What You Might Not Know About Leonardo DiCaprio's Near-Death Experiences

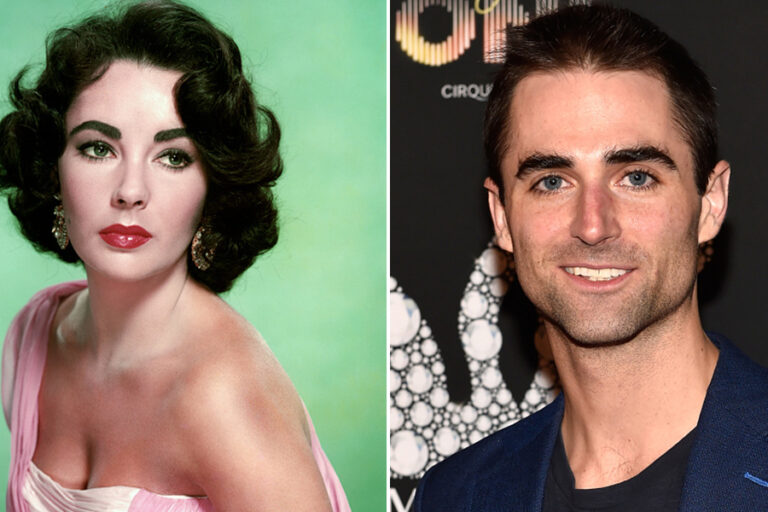

April Ross: The Untold Truth Of The Olympic Beach Volleyball Champ

The Truth About The Riots At Woodstock '99

What The Union Jack Flag Really Means

The History Of The Budweiser Clydesdales Explained

What Really Happens When You Report Fake News On Social Media