The Untold Truth Of The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse

The Book of Revelation is arguably the most mysterious, confounding, and controversial book of the Christian Bible, with many early church fathers arguing against its inclusion in the New Testament. It’s not at all clear whether the apocalyptic visions of John of Patmos–who may or may not be the same person as John the Apostle and/or John the Evangelist–is meant to be a harrowing prediction of a future tribulation at world’s end, a veiled critique of the current state of affairs in the Roman Empire, or both (or something else!). It is, however, perhaps that mystique that is part of the allure of this extremely strange chunk of Bible, some of the more enduring images of which have impressed themselves upon the popular consciousness, even among non-Christians.

Besides the Beast of the Apocalypse–you know, the one with the Mark and whose number is famously 666?–probably the best-known figures of Revelation are the riders of doom known as the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. But who are these strange equestrians? Read on, if you dare.

The surprising rider in white

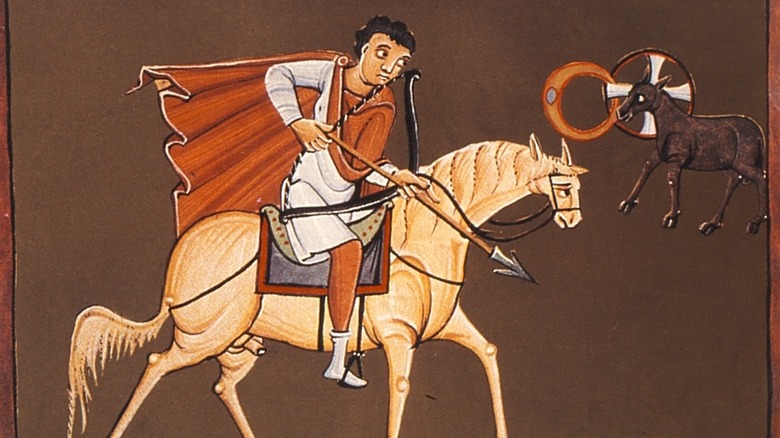

The Book of Revelation begins with John of Patmos explaining that this book is a vision revealed to him (hence the name) by an angel, after which he passes on seven mostly scolding letters to different churches in Asia Minor, and that’s when the weird stuff starts. Johnny Patmo has a vision of the throne of God surrounded by many-eyed angels who produce a scroll sealed with seven seals. Each seal that is opened will loose some fresh destruction upon the Earth. Chapter 6 tells us John “looked, and there was a white horse. The horseman on it had a bow; a crown was given to him, and he went out as a victor to conquer.” So there we have the first Horseman, but this rider doesn’t seem to fit the “canonical” list of Four Horsemen. So who is it?

As it turns out, the White Rider is the hardest to identify, but as Christianity.com explains, Revelation 6 presents the first Horseman as representative of Conquest. The bow he carries is a symbol of violence, and the crown he wears represents victory. While it might seem obvious that being conquered is pretty sucky, it has actually been a matter of debate for literally thousands of years whether the Horseman of Conquest is good or evil. Why the confusion? It mostly comes down to the color of his horse.

Christ or Antichrist?

As the Religion Wiki explains, the leading theory regarding the White Rider of Revelation chapter 6 starting in the second century CE is that this Horseman is Jesus himself. The church father Irenaeus is largely responsible for this, arguing that the white horse of this rider parallels the White Rider in Revelation chapter 19, who is much less ambiguously Jesus, being expressly identified as the Word of God. By this interpretation, the Conquest of the first rider is the conquest of the Gospel across the world as a sign of the apocalypse, something promised in the Gospel of Mark chapter 13. Also, generally speaking, white is used as a symbol of purity and righteousness in the Bible, so it stands to reason that the White Horse is something good.

However, as Evangelical theologian James Boice explains, after nearly 2000 years of people understanding the White Rider as a symbol of Christ, the perspective began to change, thanks in large part to renowned evangelist Billy Graham. Graham felt strongly that the rider on the white horse is not Christ himself, but rather an imposter Christ, i.e., the Antichrist. For Graham, the threat represented by this figure is not the destruction of a wave of conquest, but rather the deception of false religions. (For what it’s worth, Boice believed that Conquest was neither Christ nor Antichrist, merely the spirit of militarism that gives rise to the other Horsemen.)

Where does Pestilence come from?

“But,” you cry, “everyone can name the Four Horsemen, and none of them are Conquest, Christ, or Antichrist. What kind of scam are you running here? The First Rider is–famously–Pestilence.” Well, eventually, yeah. For one thing, it’s worth noting that none of the Horsemen in Revelation 6 are actually named except for Death, so all of their identities are extrapolations from their descriptions anyway. When the rider on the white horse began being identified with Pestilence is not exactly clear–for example, in the famous 15th century woodcut by Albrecht Dürer the White Rider is portrayed in a pretty conquest-y looking light–the idea was certainly in place by the 1906 edition of the Jewish Encyclopedia, which says the first rider is “probably, Pestilence.”

Part of the reason for the association may be that Revelation 6:8 says that the Horsemen would “kill by the sword, by famine, by plague, and by the wild animals of the earth.” Part of it may be Conquest’s weapon of choice. As the BBC explains, arrows have long been symbolic of disease and plague–the word “toxic” derives from the Greek word for bow–so the association would have been a natural one. Or maybe the people depicting the Four Horsemen in art and literature just felt that Conquest and War were a little too similar, so they decided to mix it up by giving the White Rider poison arrows.

The blood red rider

Revelation chapter 6 continues, saying, “Then another horse went out, a fiery red one, and its horseman was empowered to take peace from the earth, so that people would slaughter one another. And a large sword was given to him.” There’s not much ambiguity about this one. The Red Rider is pretty much exclusively identified as the Horseman of War. Red is obviously the color of blood, but the word used in the original Greek text, pyrrhos, indicates the fiery red of flames and destruction. The sword is a pretty unambiguous symbol as well.

But if the original text did indeed intend for the first Horseman to be Conquest and the second Horseman to be War, what’s the distinction there? Well, it could be as simple as the distinction between foreign conquest (seen as a noble cause) and civil war and internal strife (destructive and bloody), but Christianity.com asserts, following Graham’s conception of the first Horseman as the Antichrist, that the second Horseman is the spiritual warfare that follows in the wake of the advent of the Antichrist and his false religion, which will, of course, be accompanied by physical slaughter as well. James Boice explains that some scholars argued that the Red Rider represented not war in general, but specifically the persecution of Christians in either antiquity or in the end times (Boice himself was unconvinced).

The man in black

The description of the Four Horseman continues in Revelation 6 when the third seal opens and a rider on a black horse emerges, holding a set of scales in his hand. This rider is accompanied by a voice coming from the angels revealing this vision to John. The voice says, “A quart of wheat for a denarius, and three quarts of barley for a denarius—but do not harm the olive oil and the wine.” Unless you’re familiar with grocery prices from the first century CE Roman Empire, this statement might be a little baffling.

James Boice explains that a quart of wheat is the amount an average person would use in one day, while a denarius is a day’s wages. While, yes, a day’s wages buying a loaf of bread sounds about right in the current American job market, a denarius should have bought up to 16 times as much wheat. The barley prices are also quite high. These high prices indicate a shortage of these food staples, hence the association of the Black Rider with Famine. It’s notable, however, that olive oil and wine–something closer to luxuries–aren’t experiencing shortages. Boice suggests that this indicates a protection of the rich in the face of the suffering of the poor, such as would have been the case during the era John was writing. Which, we can all agree, sounds completely far-fetched in the modern day.

A green horse?

The fourth rider is the most famous of all, and is distinct in a number of different ways. For one, he is the only one given an explicit name: Death. Two, he’s got, like, a little buddy. Revelation 6 says, “there was a pale green horse. The horseman on it was named Death, and Hades was following after him.” For Hades, it’s probably best not to imagine the bad guy from Disney’s “Hercules” riding sidecar, but rather an embodiment of the realm of the dead that would have been known to the Jewish people as Sheol. Dürer depicts Hades as a literal Hellmouth scooping up dead bodies as the wild-eyed Rider of Death zips by with his pitchfork. (It’s also worth noting that Death is the only rider not given an explicit weapon or accessory. As a result, he’s typically depicted with a scythe or pitchfork, like you might expect.)

The other thing that might have caught your eye is the description of Death’s horse as “pale green.” The King James Version simply calls it a pale horse, which is the traditional translation, but other translations say “ashen,” “livid,” or “pale greenish gray.” The word used in the original Greek is khloros, which indicates a pale yellowish-green, and which is also the source of the word chlorophyll. This strange color for the horse is almost certainly supposed to suggest the sickly color of a rotting corpse.

The Horsemen of Zechariah

Though the Book of Revelation is the most famous occurrence of Horsemen heralding apocalyptic times, it’s not the only occurrence, nor is it the first. The minor prophet Zechariah (so-called because of the relative brevity of his book of prophecies, not necessarily because he’s less important) twice talks about visions of strange riders on horseback symbolizing the end times. In chapter one, Zechariah sees a man riding a red horse near some myrtle trees followed by red, sorrel (kind of a reddish brown), and white horses. When Zechariah asks the angel revealing this vision to him who the riders are, the angel replies, “They are the ones the Lord has sent to patrol the earth.” Their job is to watch the Earth and make sure it’s peaceful, with the implication that this will no longer be the case when Judgment Day is imminent.

The second mention of horses in Zechariah comes in chapter six, where the prophet sees a vision of horses pulling chariots. These horses are also divided by color: red, black, white, and dappled, which is, like, pretty close to the version from Revelation. When Zech asks who these riders are, the angel replies, “These are the four spirits of heaven going out after presenting themselves to the Lord of the whole earth.” They each head in a different cardinal direction, presaging John’s description of the Horsemen riding over the four quarters of the Earth.

The four devastations of Ezekiel

The author of Revelation makes use of a number of the Hebrew prophets as sources for his writings, with Isaiah and Daniel accounting for a large number of allusions, but as theologian Kenneth Gentry explains, the most influential of all the prophets on John’s vision of the future is Ezekiel. In fact, out of all the allusions to the Book of Ezekiel in the New Testament, over half of them come from Revelation. Examples include John’s descriptions of the “living creature” angels showing him his vision echoing the cherubim driving God’s chariot in Ezekiel, the use of the names Gog and Magog, the description of God’s throne room, and the glorified vision of the New Jerusalem.

As such, it shouldn’t be too surprising that Ezekiel talks about God enacting four disasters upon the Earth, too. In Ezekiel chapter 14, God speaks to Ezekiel and promises to send four “devastating judgments” against Jerusalem: “sword, famine, dangerous animals, and plague.” This is, again, like one away from what Revelation uses, but to be fair, the danger you would expect from dangerous animals is that they would kill you to death, right? So that’s basically death. In the Book of Ezekiel, God’s judgment is coming against the elders of Jerusalem for their lapsing into idolatry, culminating in Jerusalem’s conquest by Babylon, so you can see why John might echo this imagery for the tribulation of the unrighteous in the End Times.

The Horsemen in the future

Okay, so we understand that the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse represent forces unleashed by God upon the Earth that will wreak great destruction and death. But, like, what are they really? The answer to that question kind of hinges on how you view the Book of Revelation as a whole. Is it a prediction of the End Times, where we should be looking out for signs of it now? Is it a prediction of events that were to happen soon after the time the book was written? Is it a symbolic commentary on the author’s own times? Is the whole thing a metaphor? There are supporters of each of these views, and, as with all things theological, they each have their own little names.

As Got Questions explains, futurism is the belief that Revelation describes a series of yet unfulfilled future events that will literally and not metaphorically happen. Futurists are also frequently dispensationalists, which is a fancy way of saying that they believe Christians will be taken to Heaven in the Rapture before the Four Horsemen come and bring a seven-year-long period of tribulation to those who are left in the world. Billy Graham’s view that the Antichrist will come and espouse false religions that lead to spiritual warfare, poverty, and mass death is an example of a futurist interpretation of the Apocalypse.

The Horsemen in the past

Another approach to interpreting Revelation is what is called historicism. According to Got Questions, historicism says that the events of Revelation are symbolic of people and events from history, which is a somewhat less literal approach than futurism. Under a historicist interpretation, the devastations that emerge from the scroll when the seals are opened–including the seals that unleash the Horsemen–represent the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, which was the leading power in the Mediterranean world at the time of the composition of the Book of Revelation and, notably, the power persecuting the early Christian community.

With this approach, it’s pretty easy to see the course of events as represented by the Horsemen: Conquest, on his white horse, is the successful expansion of the Roman Empire under first and second century CE emperors such as Trajan and Hadrian. War, understood as bloody civil war, represents the internal strife that ultimately led to the Empire dividing into West and East and endless civil warfare. Famine represents oppression of the lower classes by the elite, and Death signifies the dissolution of the great oppressor of Christianity. That all makes a kind of sense, but be warned that historicism also goes on to argue that the Beast of the Apocalypse is the Pope and Gog and Magog are the spread of Islam, so that’s a yikes.

The Horsemen in the present? (Not our present)

The other two interpretations of Revelation are idealism, which says that the events of John’s apocalypse are purely symbolic, which is pretty easy to understand; and preterism, which is a little more complicated. As Got Questions explains, preterism espouses the belief that prophecy in the Bible is not a prediction of the future, but rather a commentary on the past. In this view, everything “predicted” in Revelation was actually fulfilled by the time the book was written, with most of them pertaining to the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE. Preterists would say that Jesus’s second coming was a spiritual one rather than a physical one, and the tribulation and judgment are ongoing processes.

Within this framework, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse represent specific events from the first century CE. Conquest, with his bow and arrows, is symbolic of the Parthian Empire who troubled the Romans in the first century, famous for their skill with the bow. War is again the civil war, rebellion, and partisan squabbles that plagued imperial Rome. Famine’s mucking about with grain and grapes represents attempted agricultural reform by the emperor Domitian in 92 CE. Death is, as ever, fairly self-explanatory.

The Horsemen as wrestlers and supervillains

Thanks in part to the indelible image made by artworks such as Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut, the idea of a quartet of destroyers sowing havoc around the Earth has become a significant part of pop culture. While the Four Horsemen naturally show up in religious and paranormal themed books and shows such as the Terry Pratchett/Neil Gaiman collab “Good Omens” and the show that lasted so long that everyone was going to appear on it eventually “Supernatural,” there are a couple of more surprising allusions as well. As the Pro Wrestling Wiki explains, the Four Horsemen were a popular wrestling stable (pun not intended) at WCW and other promotions in the 1980s and ’90s. The original lineup consisted of Ric Flair, Arn and Ole Anderson, and Tully Blanchard, but the membership rotated somewhat and included wrestlers such as Lex Luger, Sting, and Sid Vicious (not the Sex Pistol).

Possibly the most notable other use of the Four Horsemen has been within the X-Men comics and movies, where there is a major villain named Apocalypse, who often has a group of four genetically modified and manipulated mutants or other heroes serve as his Horsemen. Notable members have included Wolverine and Gambit as Death, and the Hulk and Colossus as War. The most famous member, however, is likely Angel, who was given metal wings by Apocalypse to serve as his Archangel of Death.

Disturbing Details Found In Natalie Wood's Autopsy Report

Here's What Really Happens To Your Body When You Die During A Human Stampede

The Truth About The 12-Year-Old Who Took Part In The Civil War

What Do Freemasons Actually Believe?

Here's How An Octopus Regrows Its Arms

The Uncanny Similarities Between Jeffrey Dahmer And Dennis Nilsen

The US Government's Secret Mustard Gas Experiments Explained

Here's Why It's Impossible To Own A Sample Of Every Element On The Periodic Table

Did Dorothea Puente Ever Confess To Her Murders?

This City Was Captured For Over A Year During The War Of 1812